The city as we imagine it, the soft city of illusion, myth, aspiration, and nightmare, is as real, maybe more real, than the hard city one can locate on maps, in statistics, in monographs on urban sociology and demography and architecture.

—Jonathan Raban

When I knock off work this September afternoon, around two o’clock, I’ll stick an Eckhart Tolle book in my backpack, hop on my bike, and head for the North Shore. I thought of going sailing on English Bay, or playing tennis at Jericho, or golfing at Shaughnessy, or maybe swimming laps at the Second Beach pool, but I’ve decided to do the Grouse Grind instead. Along the way, pedalling furiously, I’ll give the one-finger salute to a few road-hogging, carbon-emitting drivers before stopping in at Choices to grab a Happy Planet juice. Organically recharged, I’ll follow the seawall to the Lions Gate Bridge and over to North Van.

At the foot of Grouse Mountain, I’ll join the hundreds of other fitness buffs who scramble up the 2.9-kilometre trail on a typical summer’s day. Stumping up the Grind is a what-the-hell-was-I-thinking workout; it takes about an hour (personal best 58:45, actually, as recorded by the chip in my season pass). Up top, with luck, and once I stop feeling as if I might hurl, I’ll score a table on the patio. There, enjoying a Granville Island Lager and gazing out over the Strait of Georgia, the city, and much of the Lower Mainland, I’ll tweet about the experience, check email, and bullshit with fellow Grinders about the brilliant summer we’ve had, the awesome view, and all the poor saps who don’t live here in the world’s most livable city, at the centre of (as our licence plates assure us) the Best Place on Earth.

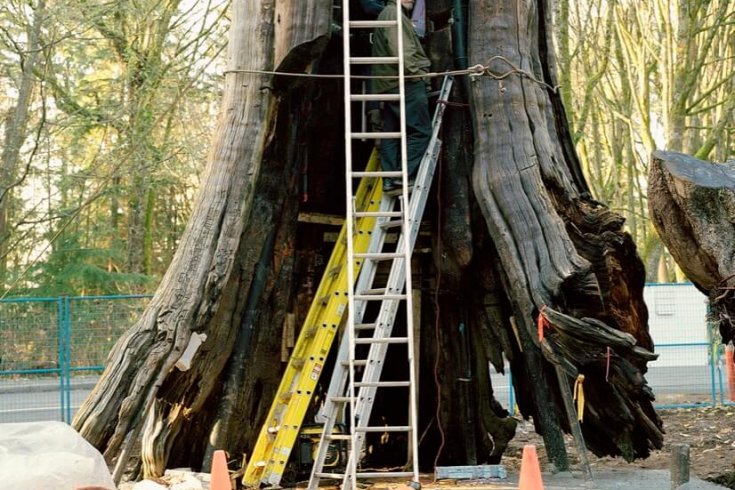

Any city of consequence is, from the outside, a lamination of clichés; Vancouver, even more than most places, lends itself to spoof. The melodramatic views, the dependable wackiness of local (and provincial) politics, the green roofs and sustainably harvested spot prawns and Critical Mass cycling rallies, and, especially, the alternating smugness and insecurity of the citizenry: what’s not to parody? Everything’s in 3-D. You want drug addiction and wrenching, in-your-face psychosis the likes of which you’ll find nowhere else? Stroll through the Downtown Eastside, a twenty-square-block human zoo. Want to visit an Asian enclave that’s a cyberlike parallel universe? Check out the Aberdeen mall in Richmond, south of the city proper: two solitudes, Pacific variety. Think you’ve got a cool urban recreational space where you live? Try the spectacular, 400-hectare promontory called Stanley Park, with its bald eagles, heron rookery, and ever-shifting vistas of ocean, mountains, and container ships at anchor, awaiting their turn at the gateway to the Pacific Rim.

The trouble with clichés, of course, is that they heighten reality while bleeding it of subtlety. And so it’s possible to be startled by Vancouver, right there in front of you, but not quite take it in, as you do a killer whale that breaches suddenly, once, before disappearing; or to admire the city without seeing beyond its fetching outline, as you might a server at Cactus Club, a “casual fine dining” chain staffed by lush young women in low-cut black dresses, some of whom are no doubt putting themselves through medical school.

“All the moms with their little yoga mats,” a friend from Toronto chuckled as we emerged from lunch in Kitsilano one day last summer, “and their fair trade lattes. And their reusable shopping bags, for buying local produce.” Well, sure, how quaint, and how handy that the caricatures are so plentiful. Don’t forget Chip Wilson’s seaweed-neutral Lululemon wear, standard issue for the yoga moms. And Gregor Robertson, our bicycle-happy mayor. And Sarah McLachlan, doing public service announcements for the SPCA. And the Dalai Lama, who visits regularly, and the snowboarders, and the life coaches, and the never-say-die No Games 2010 coalition, with their megaphones and spray paint, vandalizing the Olympic clock that has been counting down the days, minutes, and seconds until the Games begin and Vancouver takes its rightful place among the great cities of the world that have hosted the Winter Games: Sarajevo, Albertville, Nagano, Lillehammer, Calgary!

Amid the stereotypes, of course, obscured by them, Vancouverites live substantial, complicated, inaccessible lives. Newcomers say folks here are quick to engage you in a friendly chat but slow to invite you over for dinner. There may be a flaky, hippie vibe to the lineup at Trout Lake Farmers Market on Saturday mornings, but there is a seriousness of purpose as well, an act-on-it conviction that organic tomatoes from the Okanagan are in every way superior to industrial tomatoes from Mexico. Local initiatives to address the Downtown Eastside, too, are more than compulsory nods toward civic responsibility; they are attempts to ameliorate vexing problems before they ossify into permanence. In a city where crappy little bungalows go for a million bucks and many luxury condos belong to offshore owners who spend little time here, there’s real concern that Vancouver has become a high-end global tourist destination young and working-class people can no longer afford.

Social issues are kept front and centre by the same smart, committed cadre of activists who remind you that The Corporation (book and documentary) was done by Joel Bakan, a cooler, post-doc version of Michael Moore (Bakan teaches law at UBC and plays jazz guitar on the side). Some of the most high-powered people in town sit on the board of Streetohome, an agency created to address homelessness. A 2,000-square-metre community “farm” has been established in the middle of the Downtown Eastside. A local writer, Charles Montgomery, launched a homestay program for Olympic visitors, with half the proceeds going to charity. Tom Cooper, a Christian minister who heads City in Focus, organized a 2010 outreach initiative that has brought together more than 1,100 religious and community organizations. A young activist, Matt Hern, started a car-free day on Commercial Drive a few years ago that this June will involve half a dozen neighbourhoods. There is a palpable sense of participating in a grand civic experiment; this adolescent city is a work-in-progress, and many citizens, one way or another, eagerly partake in the work.

MR. GREEN

“Green” is not merely a buzzword, a mantra, or a way of life for many people here; it’s an orthodoxy. Vancouver has long served as a repository for sustainable thinking. David Suzuki was a lonely voice decades before people like Bono and Al Gore and Leonardo DiCaprio joined the choir. Greenpeace set sail from these shores on its international mission; and the new wave of eco-warriors, though you may not know their names, is even more directly shaping the global agenda. It was the UBC economist William Rees who made graspable the notion of the carbon footprint—essentially, one’s impact on the planet, a yardstick now widely used to measure an economy’s capacity to sustain itself. At Clayoquot Sound on Vancouver Island in 1993, Tzeporah Berman was a young tree hugger; now, in a volte-face that angers many of her fellow activists, she argues for the very things she once questioned, such as wind farms and tidal power and run-of-river projects, believing the issue of climate change is so urgent we must exploit every alternative energy source we can. Meanwhile, from his office at Simon Fraser University, the economist Mark Jaccard, a member of the 2007 Nobel Peace Prize–winning Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, consults to NGOs and governments the world over, basically arguing that we don’t have time to effect change through smart hydro meters and ten-cent plastic bags, that rigorously enforced legislation is the only way to go.

Mayor Robertson, too, with his shirt model looks and too-good-to-be-true bio (international sailor, Cortes Islander, organic farmer, family man, green entrepreneur, NDP member of the provincial legislature), is more easily caricatured than fathomed. Having vowed to create the world’s greenest city, he has, predictably, posed for photo ops in the community garden he put in at City Hall and cycled for the TV cameras in the bike lane he dedicated on the Burrard Bridge. But he’s done considerably more. The city’s hiring of Sadhu Johnston, a driving force behind Chicago’s Greenaissance, was a coup. Its Vancouver 2020 report, which Robertson unveiled at an environmental conference last fall, was notable for its eschewing of vague bromides in favour of hard targets: a 33 percent reduction in greenhouse gas emissions from 2007 levels; the creation of 20,000 green jobs; a 20 percent improvement in the efficiency of all buildings. And the city’s brand (yes, cities these days are branded) is “Green Capital,” after the hoped-for flood of investment in sustainable businesses. There is even talk that City Hall may be a way station en route to the premier’s office in Victoria—an office now occupied, for a third term, by the Liberal Gordon Campbell, himself a former Vancouver mayor.

Sustainability has become the defining narrative of Robertson’s mayoralty and may well be his legacy; if he does set his sights on provincial pastures, he’ll have serious green cred. By the most dependable benchmark we’ve devised—GHGs, or annual greenhouse gas emissions per capita—Vancouver (at 4.9 tonnes) is already the most eco-friendly city in North America, well ahead of New York (10.5 tonnes), Los Angeles (13 tonnes), Seattle (11.5 tonnes), and Toronto (11.6 tonnes). And in just about every reckoning of the world’s eco-friendly cities, Vancouver ranks up there with Reykjavik, Copenhagen, and Malmö. We have the most advanced electric vehicle infrastructure and municipal bylaws in North America, and Nissan will introduce the world’s first all-electric, zero-emission vehicle, the Nissan LEAF, here in 2011, ahead of the global rollout in 2012. The Athletes Village at Southeast False Creek will likely be the largest LEED gold–certified development in the country. Vancouver diverts more than half its recyclable waste—the average among Canadian municipalities is 22 percent—and aims for 70 percent by 2015. Methane from the landfill south of town warms forty hectares of greenhouses for local vegetable growers. It’s no surprise that the billionaire Aquilini family has turned its attention to greener waste management, believing that public education—and a few years—is all that stands between the city’s practice of trucking 500,000 tonnes of garbage annually to Cache Creek, in the BC interior, and the sort of waste-to-energy incineration that has reduced emissions in cities like Vienna, Osaka, and the Aquilinis’ ancestral hometown, Brescia, in northern Italy.

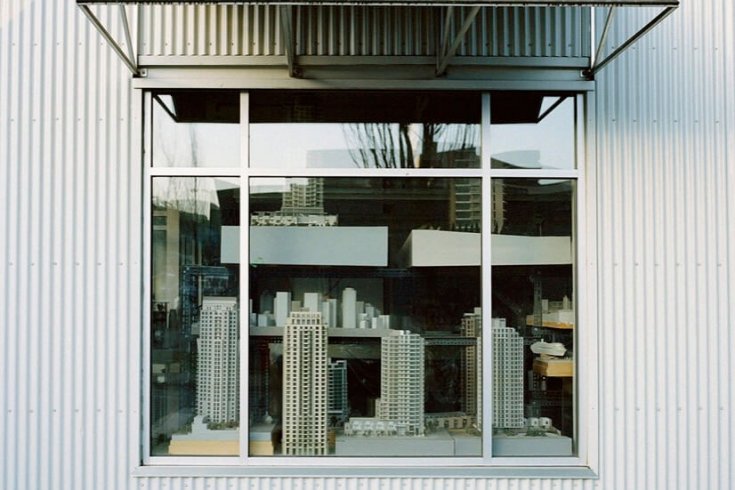

The green ethos pervades the city’s planning department, and the configuration of Vancouver’s glass-towered downtown—the work of former planner Larry Beasley—is so widely admired that much of the urban planning world comes here to pace our sidewalks, the better to understand view corridors, high-rises on retail pedestals, and the commotion of people and cafés and bicycles and townhouses that the urban theorist Jane Jacobs called the “sidewalk ballet.” Beasley was a master at extracting heritage, green space, and public amenities from developers in return for density. Never mind that many critics find the mould rigidly standardized and the city full of monotonous, copycat architecture; Beasley, who left in 2006 (and took a good chunk of the planning department with him), is always jetting off to Rotterdam or Dallas or the Emirates, adapting “Vancouverism” on four or five different continents.

Many local architects are also in demand elsewhere. James Cheng, who designed the Shangri-La hotel and condo complex (at 200 metres, Vancouver’s tallest building), is responsible for the Shangri-La now going up at Adelaide and University in Toronto. Peter Busby is often in Abu Dhabi. John and Patricia Patkau are developing a massive project for the University of Pennsylvania. Chinese planners have a particular fondness for Vancouver talent: Bing Thom, an Arthur Erickson acolyte who’s done a dozen notable buildings here, is working on Dalian New Town, a city for a million people; Nick Milkovich has created a 110-hectare community for Weihai’s Golden Thread Hill; and Hotson Bakker Boniface Haden is designing Crystal City, an entire residential and commercial neighbourhood in Beijing. In the hyper-build lead-up to the 2010 Games, Vancouver devised a carefully systematized approach to the built environment that we now export around the globe.

Indeed, if the measure of an idea is how widely it’s disseminated and how passionately it’s embraced, this city is anything but the kayaking, navel-gazing, pot-smoking Lotus Land of popular imagination. It’s a hotbed of entrepreneurship and creativity. “Doesn’t anybody here work? ” a visitor joked one October afternoon as we walked past a surprisingly active Kits Beach. Yes, people do work, all the time—just not in head offices, since we have very few. They launch start-ups, they freelance, they find Wi-Fi spots, they unfurl blueprints at Starbucks. They invent, imagine, concoct. Sure, we have Jean and Alastair Carruthers to thank for Botox, as apt a metaphor for superficiality as you can imagine. But we also have Alisa Smith and James MacKinnon to thank for the 100-Mile Diet, which began as a blog on thetyee.ca and has become shorthand for the global locavore movement (in much the same way that, about twenty years ago, Douglas Coupland’s first novel coalesced the skeptical, cockeyed anomie of the day into Generation X).

Laugh at the clichés, but understand that leading-edge thinking elsewhere is often the norm here. From North America’s only supervised injection site to a police chief who openly supports the idea of making addiction a public health issue, not a criminal one; from UBC’s breakthroughs in sports medicine to the bold social experiment of the Woodward’s development, which combines public housing with high-end units; from inventors like Phil Nuytten, the father of the underwater Newtsuit, to Internet millionaires like Markus Frind (plentyoffish.com) and Stewart Butterfield (flickr.com); from D-Wave’s breakthrough in quantum computing to Saltworks Technologies’ cost-effective desalination system, Vancouver incubates far more than its share of striking new ideas. If the continent is a centrifuge, flinging novelty and eccentricity and experimentation to the margins, then what Portland and Los Angeles and Seattle are to the US—last-frontier outposts of wisdom and wackiness, civic laboratories for new ideas—so, in many ways, is Vancouver to this country and, indeed, the world.

Which is one reason why that hateful phrase “world class” has lately entered the local vocabulary.

THE WORLD-CLASS THING

Attention, gourmands: heard about our restaurants? Bon Appétit spoke of Vancouver’s “thriving Asian restaurant culture, possibly the most vibrant in North America.” Beppi Crosariol suggested in the Globe and Mail that Toronto may have been overtaken as the country’s dining capital. Pointedly bypassing Toronto and Montreal, culinary titans Daniel Boulud and Jean-Georges Vongerichten opened their first Canadian rooms here. The hell-bent Gordon Ramsay has described Araxi, up the road in Whistler, as “the best restaurant in Canada.” And did you know that Pino Posteraro, chef and proprietor of Cioppino’s in Yaletown, got invited to cook at James Beard House in New York? When you consider the concentration of options, is Vanhattan really such a stretch? We’re world class, right?

“The world-class thing reminds me of Toronto in the ’80s,” says Anthony Perl, the silver-haired head of urban studies at Simon Fraser University. A New Yorker, he came to Vancouver four years ago by way of Harvard and the University of Toronto. “When people start saying that, alarms should go off in city planning and governance minds. They thought they’d invented the answer; if something was done in Toronto, it must be successful. We risk that here—our megaproject mania for highways, SkyTrains to UBC, stuff like that.” UBC president Stephen Toope has announced his intention to create a world-class university.

The food scene is invoked as the pudding in which to find world-class proof, and diverse influences certainly add depth to a cuisine blessed with wonderful local produce and seafood. Vij’s, off Granville Street, was referred to by the New York Times as “easily among the finest Indian restaurants in the world,” and critics who know Japanese food rank Tojo’s, on Broadway, up there with the best of them. From the rough-and-tumble seafood shack Go Fish, to the elegant refinement of West and C and db Bistro Moderne, to the profusion of first-rate Asian spots, there’s no doubting the richness of the culinary landscape; but the microscopic attention paid to it suggests, frankly, a dearth of more substantial topics.

Restaurant criticism here, as in many a burgeoning city, sometimes resembles professional cheerleading (in which, as editor-in-chief of Vancouver magazine, I can fairly be accused of participating) or, on the web, endless amateur nitpicking. So many people spend so much time deconstructing and photographing and blogging about what they put in their mouths that you’d think they were preparing for an exam. Dining has as much to do with fashion as food, of course, each place outdoing the last in lavishness (the plushly expensive Coast) or thrift (the minimum-security Campagnolo), the daily ebb and flow recorded and amplified for distribution by a small army of “experts”—bloggers, reviewers, oenophiles, free-ride artists, all of them one click away from the next BC wine tasting, small plates sampler, or media preview. Dining out is indeed a treat—excellent, diverse, reasonable. But in what world-class city would a chef’s departure from a restaurant make front page headlines, as Rob Feenie’s from Lumière did a couple of years ago? Or would you have trouble hailing a cab at 10:30 at night? Or would Presbyterian liquor laws endure into the twenty-first century?

The professional sports scene also gives the lie to Vancouver’s longed-for status. Consider the anguish occasioned by the Canucks’ failure to go deep in the NHL playoffs each year—compost for untold column inches and endless hours of talk radio. The team’s long-ago brushes with glory (they lost to the Islanders in the 1982 Stanley Cup final and to the Rangers in 1994), and the local reflex of invoking these as moments of sporting significance, serve as inverse reminders that we’ve lacked an NBA franchise since the Grizzlies relocated to Memphis in 2001, and that the nearest Major League Baseball game is a couple of hours down the road in Seattle. The NFL Seahawks remind us that we have only the CFL Lions. The junior hockey Giants and professional soccer Whitecaps do well enough, but we’re talking WHL and MLS here, acronyms that even a sports fan may take a moment to unpack.

Besides a full roster of major-league franchises, Vancouver lacks more basic indicators of civic heft and maturity. Until last summer, when the Canada Line opened, there was no direct public transit route from downtown to the airport. YVR serves up to arriving visitors a brief parody of Northwest Coast culture—Bill Reid sculptures, fake waterfalls, canned bird noises—before depositing them in the midst of unending construction. Pacific Central Station, too, is a tacky interface between this supposedly world-class city and the world. “For lots of train travellers, their first view of Vancouver is seeing people passed out in Thornton Park,” says Anthony Perl. “We should be presenting them with the face of our city; instead, we present them with a very different part of the anatomy.”

He rhymes off a list of shortcomings you won’t find in great cities: no downtown university with an adjoining student neighbourhood; no broad pedestrian promenade; no major civic square. A great city is a world unto itself, defying attempts to break it into its constituent elements. Berlin, Rome, New York: these are urban confabulations, memory vying with amnesia, civic magma bubbling and hardening under the weight of history. World-class city? It’s the world, not the city, that gets to decide. Penelope Chester, the daughter of a French publisher, studied in Paris and New York and Boston and travelled the planet before spending a year and a half in Vancouver working for an international NGO. Now based in Liberia, she liked Vancouver but noted that locals “have an exalted sense of their city’s standing in the world, without much experience of the world to support it.” If the “world-class” discussion teaches us nothing else, it confirms that such assessments—like claims of genius or insanity—are most reliably left to others.

BOB THE BUILDER

Trim, affable, casually spiffy, sometimes frenetic, Bob Rennie is a fifty-two-year-old condo marketer, but that description does not begin to reflect his role or his standing in the city. Chauffeured about in his Audi S8 V-10 or his Bentley, he’s more or less constantly on his BlackBerry, from six in the morning till midnight, saying (or thumbing) things like “I’ll have a word with Rich,” meaning Coleman, the provincial housing minister; or “I’ll see what Francesco thinks,” as in Aquilini, who owns the Canucks and GM Place; or “Jeff’s away till the twelfth,” meaning Wall, the Vancouver photographer whose show at the Museum of Modern Art in New York a couple of years ago earned stellar reviews and whose works sell for a million dollars a pop. Rennie seems to know almost everyone, and almost everyone seems inordinately fond of him.

Rennie made his fortune persuading people to queue up in the rain at 5 a.m. to put down a deposit on the idea of (let’s say) 725 square feet of marble-topped, burnished steel “lifestyle.” People were buying an idea rather than a condo, since the condo they were buying was actually nothing more than a hologram of aspiration shimmering above a muddy hole in the ground. And so it would remain for months, or years, during which time their deposits would be used to complete the project. Rennie Marketing Systems took a cut—as much as $50,000 per unit—and Rennie turned a good chunk of it into a contemporary art collection (some 1,000 pieces) that rivals any in the world and explains his presence on the American Acquisitions Board of the Tate Modern in London, England.

This morning, BlackBerry in hand, wearing a crisp white shirt, black trousers, black and white sneakers, designer specs, and a red hard hat, Rennie is showing me through his makeover of the Wing Sang Building, the oldest in Chinatown. When all is said and done, the Rennie Museum will cost him something like $20 million. (“I’m not really that rich,” he says with a shrug. “I’m all in—this is my life now.”) Besides a home for his offices, the space houses an appointment-only showcase for some prized pieces (which are otherwise kept in an industrial warehouse in South Vancouver). It lets him collaborate with curators around the world to stage exhibits (the first features the work of Palestinian conceptual artist Mona Hatoum, whom he collects). The audacious renovation signals, and will accelerate, the evolution of Chinatown, the next part of the city to be gentrified and resold (with the help, no doubt, of Rennie Marketing Systems). It positions him at the crossroads where business abuts culture, and at the fulcrum of the East-West teeter-totter. And it demonstrates his money-meets-mouth commitment to the arts, in a city where the rich don’t always share his priorities.

“Would you consider what we’re doing here,” he asks slyly, above the din of mitre saws and nail guns, “a challenge to others to participate? A lot of people in this town say, ‘Why put all that money into an art museum? If you have $20 million, why wouldn’t you buy a bigger house? ’ You run across that mentality all the time.”

Vancouver is awash in private-jet wealth. Jimmy Pattison, one of the best-heeled men in the country, is the informal head of a local billionaires’ club. But with notable exceptions (including Southam heiress Martha Lou Henley and developer Michael Audain), the moneyed class lacks the cultural IQ you find among the elite in established cities. Mining financier Frank Giustra donated $100 million to the William J. Clinton Foundation, and flies the former US president around the globe in his MD-87, promoting their humanitarian projects (and his own mining concerns); he gives his time and money to Streetohome, the homelessness agency; yet he seems to have little interest in ensuring his hometown has a decent opera company, ballet corps, theatre scene, or art gallery.

“Partly it’s that idea of generational wealth that Will and Ariel Durant talk about in The Lessons of History,” says Tom Cooper of City in Focus. “Vancouver’s rich are still in acquisition mode. It’s the third and fourth generation that starts thinking about endowing a chair or funding the arts or charities. We don’t have Carnegies and Rockefellers here, because the wealthy families are still too busy making money to stop and wonder what to do with it.”

“The problem in this city,” suggests Bob Rennie, “is that people put you on their boards because they want your money, not your energy or your ideas.” He doesn’t single out the decrepit, antiquated Vancouver Art Gallery, but his disdain for the VAG and its director, Kathleen Bartels, is no secret. The securing of a new site and construction of a new VAG seemed assured a couple of years ago, but the site acquisition fell through and major funding has been scarce. “I think they’re going about it the wrong way,” says Rennie. “‘We need the grand gesture: let’s hire a starchitect, let’s make a statement, let’s go for the splashiest exhibition.’ It grows out of a small-town mentality. We have people here who are royalty in the international art world: Jeff Wall, Ian Wallace, Roy Arden, Brian Jungen. Did you know that Rodney Graham has a major show in Basel this June? But oh no, we couldn’t possibly be good enough to stand on our own merits.”

THE BLUE BOY

My first memory of Vancouver, as a pubescent kid in the early ’60s: I’m stepping off the plane from Toronto with my father and brother into a foggy evening ripe with sulfurous emissions from the pulp mills along the Fraser River.

We check in to a place on Marine Drive called, oddly, the Blue Boy, after the eighteenth-century Gainsborough portrait that’s cheaply reproduced in the lobby of the motor inn—or maybe it’s not so odd, in a city named after the stern British Royal Navy captain who explored these shores at the end of the eighteenth century. While my brother and I fetch buckets of ice or run riot in the halls or shoot pool in the basement, Dad—employed by a union based in Pittsburgh—conducts business from our room, plotting with a cast of characters out of Damon Runyon, ordering in Chinese food and, at strange hours, arranging for a bottle of rye by asking for “Speedy Delivery.”

I vividly recall, less than half a century ago, picking blueberries and galloping horses just off No. 3 Road in Richmond, then a country byway with open sewage ditches; it’s now a retail mecca of malls, franchise operations, and sleek Mercedes. Downtown, my brother and I were stunned to realize you could step off the curb of the busiest street and all traffic would halt—no crosswalk needed. East Hastings, where Dad took us for seafood at the Only Café, was more gruff pageant than horror show, full of abject loggers and miners and stevedores and what were then called, without apology or embarrassment, drunken Indians. To us highly sophisticated easterners, the place felt like a frontier town.

It’s easy to forget now, a quarter century after Expo 86 introduced the world to Vancouver (and Vancouver to the world), easy to forget after the exodus from Hong Kong in the ’90s altered the city’s demographic profile and fuelled a real estate boom, easy to forget now that Hermès and Coach and Gucci fill our shop windows—and especially easy to forget during the klieg-lit invasion of the Winter Olympics—what a small city this is. With a population of about 600,000, it’s a quarter the size of Toronto proper. Edmonton, Calgary, Montreal, and Ottawa have more citizens. Hell, Mississauga has more. Winnipeg has more. Vancouver’s American analogues are not Chicago and New York, but Charlotte, Memphis, El Paso. Include the metro area, and the population swells to 2.2 million, a third of metropolitan Toronto’s. If this city were an actor, it would acquit itself beautifully in a supporting role—Philip Seymour Hoffman before Capote. If it were a fighter, it would be a middleweight, albeit one so slick and well marketed that you think of it as belonging among the heavyweights—any of which would, in fact, clobber it.

Vancouver’s youth, like its size, is easy to overlook. From the air, the downtown commercial grid, circumscribed by salt water and shining in the sun, calls to mind a sort of a mini-Manhattan, as snugly fitted as a Lego project. But look closely, and you’ll notice that only recently have the central buildings started to poke dramatically upward; only now is a mature skyline taking shape, the last of the baby teeth being displaced. Not so long ago, this thrumming, cosmopolitan nexus was little more than old-growth forest. In 1881, three decades after St. Michael’s College was founded in Toronto, it was a rudimentary settlement of some 1,000 souls. Unlike the principal cities of the East, Vancouver is only now starting to take its place in the world, to understand the value of heritage, to unfurl a history and plot a future.

One night at the Blue Boy, a union pal of my father’s drunkenly informed me that he just might have found the cure for my virginity. He was an expert in such matters, and he figured a certain young woman in the coffee shop could be the ticket. “Partner,” he said with a wink, “why don’t you head down and give it a shot? ” When he volunteered to come along for moral support, I made some excuse, but of course I headed downstairs by myself at the first opportunity.

I spotted her at once, as would anyone with a Y chromosome. She was stunningly endowed, effortlessly lovely; notepad in hand, she was absorbed in the task of taking an order. I sat at the counter, trembling and dry mouthed. Only when she came over and handed me a menu, brushing aside a tendril of blond hair, did I realize she was not a young woman at all. She was a girl, scarcely older than I. Her name was Lila; her name tag said so.

Ever since that stay at the Blue Boy, through many years in Toronto and stints of living abroad and a permanent move to the West Coast in 1989, I’ve associated Lila with Vancouver—younger than she seems, less sophisticated than she might like, undeniably radiant, proud to be attracting attention but not quite sure how to deal with it, a little self-conscious as the first complications of maturity settle upon her. You can’t help but marvel at her good fortune, her beauty. You admire the earnestness of her endeavours. You envy the wealth of her possibilities.

You wonder what she’ll become.