On January 29, 2020, Kate Laskowski sat down at her desk at the University of California, Davis, and steeled herself to reveal a painful professional and personal saga. “Science is built on trust,” she began in a blog post. “Trust that your experiments will work. Trust in your collaborators to pull their weight. But most importantly, trust that the data we so painstakingly collect are accurate and as representative of the real world as they can be.”

Laskowski was relatively new to her job as an assistant professor in the department of evolution and ecology. She had been appointed in 2019 to a tenure-track position, a precarious state wherein academics spend several years earning the privilege of being brought on permanently—in large part by publishing in as many academic journals as possible. And yet here was Laskowski, about to besmirch a healthy portion of her own impressive research history. “When I realized that I could no longer trust the data that I had reported in some of my papers, I did what I think is the only correct course of action,” she wrote. “I retracted them.”

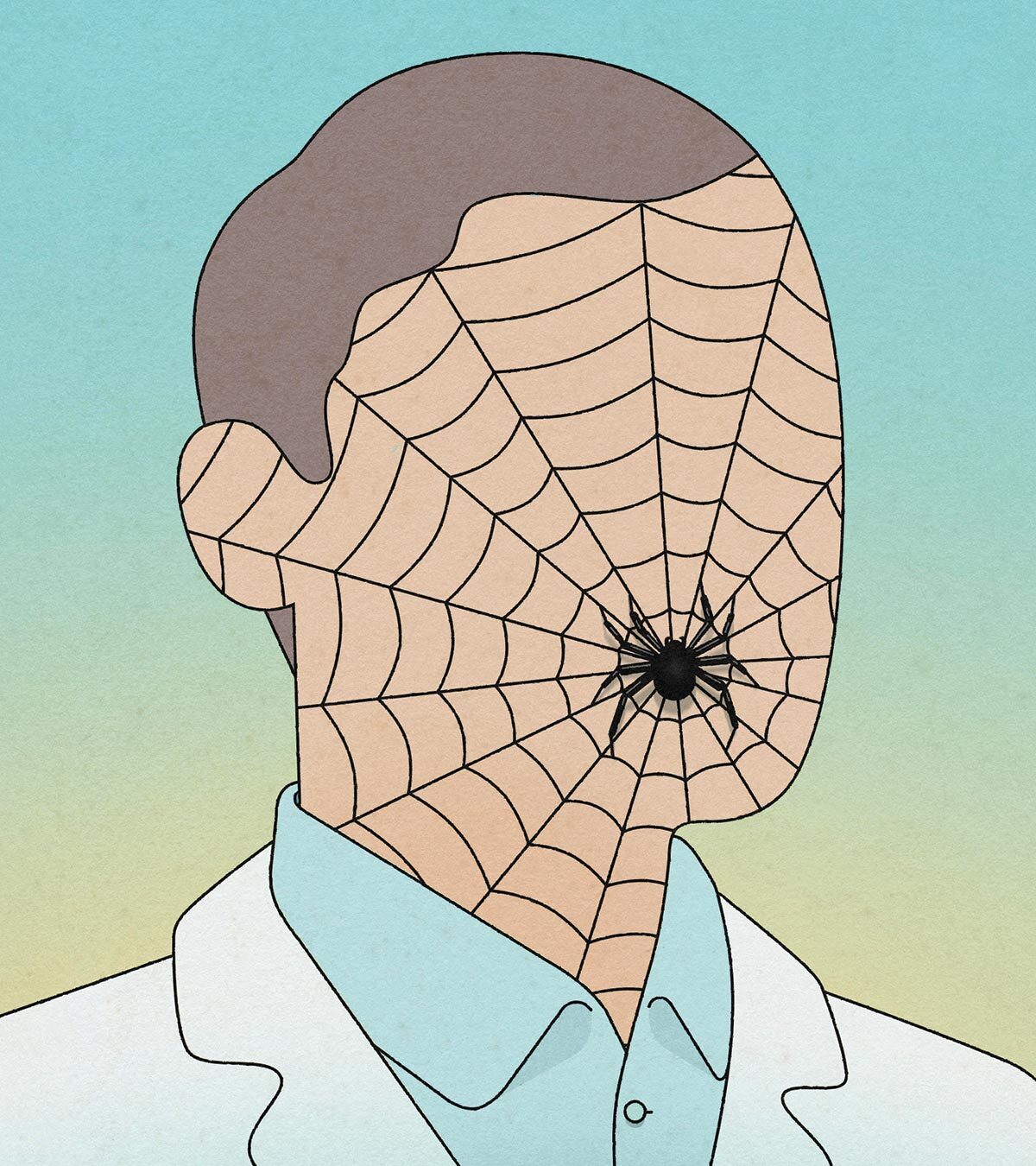

Laskowski revealed that her ambition had drawn her into the web of prolific spider researcher Jonathan Pruitt, a behavioural ecologist at McMaster University in Hamilton, Ontario. Pruitt was a superstar in his field and, in 2018, was named a Canada 150 Research Chair, becoming one of the younger recipients of the prestigious federal one-time grant with funding of $350,000 per year for seven years. He amassed a huge number of publications, many with surprising and influential results. He turned out to be an equally prolific fraud.

When Pruitt’s other colleagues and co-authors became aware of misrepresentations and outright falsifications in his body of work, they pushed for their own papers co-authored with him to be retracted one by one. But as they would soon learn, making an honest man of Pruitt would be an impossible task.

Laskowski first met Pruitt at a conference, and his reputation preceded him. “I knew he was doing cool and exciting work,” she says. A larger-than-life personality, Pruitt—who mostly studied “social spiders,” which live in groups or colonies—appeared to love mingling at conferences, sharing his latest research and gossiping with colleagues. “He is very charismatic and an incredibly fast talker. He is just super hyper social,” says Laskowski.

Collaboration on research projects in the sciences is common, but according to those who knew him then, Pruitt was unusually generous, even seeking out junior academics to partner with. At conferences, Laskowski says, he would host workshops for colleagues he called the “rising stars of behavioral ecology.” Attendees would discuss the big research questions and propose projects to answer them, with Pruitt offering to collect the data. It was a big deal for a graduate student still finishing up her PhD or a pre-tenure professor to share authorship with one of the field’s biggest names.

Typically, academic research involves designing an experiment, collecting data—whether through fieldwork or the gathering of existing data points—and then feeding that into statistical models to determine trends and correlations that test the initial hypothesis. If a finding is new or noteworthy, and particularly when a researcher has plausible evidence to support their hypothesis, they will present their work at conferences and write a paper with the hope of being published in an academic journal. Some of the fun parts of science, Laskowski says, “are coming up with the ideas and designing the experiments.” With Pruitt, she didn’t have to deal with the tedium of collecting data. It added an extra dimension to his generosity—that he would let his junior co-authors do the coolest parts of the project. He became a friend and mentor, even writing her a recommendation letter when she went on the job market.

Still, Laskowski was aware of a whisper network surrounding Pruitt. How was he publishing as much as he was? And was it really possible that so many of his experiments had ideal outcomes? At a conference presentation in New York, Laskowski found herself being questioned about the methodology of a paper she had co-authored with Pruitt. “This woman was really hammering me at the end of one of my talks,” she says. “I said, ‘I don’t know; Jonathan collected all the data,’ and then she backed off.” When she later relayed this to Pruitt, she says, he told her to ignore it; Laskowski got the sense that the woman asking questions was just a competing academic with an axe to grind.

That academic was Lena Grinsted, an evolutionary biologist at the University of Portsmouth in the UK who was very familiar with Pruitt and his work. Grinsted first heard about Pruitt when she was beginning her PhD in Denmark, in 2010. “He was already on a steep, progressing curve,” she says. She wrote a sort of fan letter: Hey, I like your science. She had plans to conduct some social-spider experiments in India, and she somewhat boldly asked him if he wanted to join her.

In an academic version of a meet cute, Pruitt showed up in India, and the pair embarked on field research together. Grinsted was excited that a superstar professor wanted to work with her. However, she found Pruitt surprisingly laidback about the actual research. “I expected him to hit the ground running, and it wasn’t like that at all,” she says. He didn’t seem worried about the details. His work struck Grinsted as off-the-cuff bare minimum—hardly what she had been expecting from a big name in the field. They co-designed an experiment, divided responsibilities, and then worked together closely to collect the spiders. At some point, she says, Pruitt went into his room and emerged with a data set a few days later.

During the trip, Grinsted gave Pruitt the benefit of the doubt. But back home, after she looked at his analysis, she was perplexed. “Everything he analyzed was super significant,” she says. Pruitt’s data sets—later reflected in papers published in Proceedings of the Royal Society B and Animal Behaviour—demonstrated a strong correlation between individual spider personalities and tasks they performed. For example, bolder spiders were more likely to be found capturing prey. This had the potential to shape how we think about animals and the ways in which they relate to one another.

The results were exciting and were what Grinsted was hoping they would find after spending time in the field. But when she ran the data analysis herself, she found differences in all the outcomes. Not every question had a significant answer, as Pruitt’s analysis had suggested. “None of the associations he was reporting were true,” she says. When she asked him about the disparity, he played things extremely cool. Maybe it was because they used different software, he offered. Or perhaps it was because of slight differences in their data sets? (Pruitt did not respond to interview requests.)

What Grinsted didn’t know then was that Pruitt wasn’t just manipulating the analysis—he was making up the data. He was taking values and duplicating them, copying, pasting, and multiplying them to make it look natural, and all in a way to arrive at outcomes that would produce the most interesting possible conclusions. “And if he’s manipulating the data points to fit the hypothesis, then we are much more likely to get that published in a good journal,” says Grinsted.

Pruitt is far from the only superstar researcher publishing in highly ranked journals who has been caught by a dragnet of data accountability. In July 2023, then president of Stanford University, Marc Tessier-Lavigne, announced his resignation when it was revealed that he had contributed to twelve papers containing manipulated data (though a scientific panel found no evidence he had engaged in the misconduct himself). Dan Ariely, a behavioural economist at Duke University who studies honesty, faces allegations that he manipulated data to make outcomes more appealing to both fellow scientists and the public.

Concerns about data manipulation and the rising number of retractions have been topics of conversation within academia for more than a decade. These concerns have even given rise to a popular website, Retraction Watch, co-founded by two journalists with academic backgrounds, Adam Marcus and Ivan Oransky. Retracting a paper simply means that it is flagged as sufficiently flawed that any reader should be wary; rarely, when the research in question poses ethical, privacy, legal, or health issues, papers will be made inaccessible. The reasons for retraction vary, including clear instances of fraud, plagiarism, or other forms of misconduct. Some researchers discover errors in their own work and seek to self-retract. According to data from Retraction Watch, forty-four journals reported retracting a paper in 1997; in 2016, it was 488 journals. And the number of retractions has continued to rise, with a sharp increase during 2020 and 2021, especially related to iffy COVID-19 papers, including a 2020 study that linked 5G cellphone technology to the creation of coronaviruses.

According to Nature, upward of 10,000 retractions were issued in 2023. More papers are being released, including by pay-for-play paper mills, but the rate of retractions has more than tripled over the past decade, the journal’s 2023 analysis suggests. Many attribute the rising rate of retractions to academia’s high-pressure publish-or-perish norms, where the only route to a coveted and increasingly scarce permanent job, along with the protections of tenure and better pay, is to produce as many journal articles as possible. That research output isn’t just about publishing papers but also how often they’re cited. Some researchers might try to bring up their h-index (which measures scientific impact, based on how many times one is published and cited), or a journal might hope that sharing particularly enticing results will enhance its impact factor (calculated using the number of citations a journal receives and the number of articles it publishes within a two-year period).

Elisabeth Bik, a Dutch American microbiologist, left her industry job to become one of the key voices routinely questioning data and image manipulation, in part through her blog, Science Integrity Digest. When it comes to fraud, she told me, “the whole system is set up [to] reward cheating in a way, because there are very few consequences.”

When Grinsted started to suspect Pruitt of malfeasance, she warned colleagues that his results should be taken with a grain of salt. Some suggested she was overstepping.

After she declined an offer to work with him, she says, Pruitt started telling them that Grinsted had plagiarized his work and couldn’t be trusted. She found out later he’d requested information from two of her employers, both universities, and was handed access to her correspondence regarding concerns about his conduct. “It was extremely unpleasant to know that he suddenly had access to my private emails,” says Grinsted. “He was trying to make life unpleasant for me.”

Years after Laskowski published her papers with Pruitt, she was contacted by a colleague who had spotted duplicates in the data. When she reached out to Pruitt, she says, he offered a breezy explanation: it was a methodological misunderstanding. She was under the impression that each spider was observed individually, but he had observed them in groups. But when she went back and ran the analysis without what she considered “the bad data,” the hypothesis was rejected. Laskowski’s heart dropped.

Pruitt gave lots of explanations. Mistakes happen all the time, he told her, and he wrote up a brief correction explaining that their methods weren’t clearly articulated. “I remember feeling stressed because things were moving so incredibly fast,” she says. Laskowski didn’t want to issue the correction because she still didn’t understand what was going on with the data. And she had a sneaking suspicion that Pruitt wasn’t being entirely forthcoming. Still, Laskowski says, Pruitt agreed that there were irreconcilable problems with the data, and they were seemingly on the same page about a course of action: they decided to request a retraction from the publisher of the paper, The American Naturalist.

When Daniel Bolnick, then editor-in-chief of The American Naturalist and evolutionary biologist at the University of Connecticut, was tipped off in late 2019 about the problems with the Laskowski paper, he, too, attempted to make sense of Pruitt’s data. Bolnick considered Pruitt a friend. They first met when Bolnick visited the University of Tennessee, where Pruitt was finishing up his PhD. Over the years, Bolnick championed Pruitt’s career, writing him recommendation letters and nominating him for awards. Pruitt was so keen and full of promise, it was a pleasure to help him climb the ladder so rapidly and assuredly.

Pruitt seemed grateful for Bolnick’s swift response to concerns about his work and tried to explain why the data irregularities were perfectly reasonable. At face value, it seemed to Bolnick that they might be, but after some digging, he realized Pruitt’s rationale wasn’t plausible. In March 2020, Bolnick formed a committee to investigate the six Pruitt papers published by The American Naturalist. Laskowski’s blog post unleashed what she refers to as “a tsunami of chaos” in the biological ecology community, and several journals began reviewing Pruitt’s publications. The mess started circulating on social media under the hashtags #pruittdata and #pruittgate as it increasingly appeared that he had used formulas to fabricate data, among other tactics.

Drawing on their friendship, Bolnick sent Pruitt a polite but terse email: “If, and I emphasize ‘if’, there is any truth at all to suspicions of data fabrication, I think you would best come clean about it as soon as possible, to save your colleagues’ time right now sorting the wheat from the chaff.” Bolnick and another colleague offered to publish on their joint blog any statement Pruitt might wish to make. But Pruitt’s abashed helpfulness shifted. Now agitated, he challenged the retraction of a paper published with Laskowski earlier and suggested that the colleagues Bolnick had gathered to assess his data weren’t suitable for the task. At some point in the midst of all this, he got a lawyer.

In May 2020, the University of Chicago Press—which owns and publishes The American Naturalist—received a letter from Marcus McCann. He identified himself as Pruitt’s lawyer and asserted that the journal should not proceed with any further actions regarding Pruitt’s work. Pruitt’s co-authors had also previously received letters, and they were deemed sufficiently threatening that many were now second-guessing their participation in the retraction process. (Almost everyone I spoke to for this story paused at some point to note that they were mindful of their words because Pruitt is notoriously litigious.) Once worried about their reputations, the journals and Pruitt’s colleagues were now equally worried about being sued.

McCann demanded that Bolnick recuse himself from any investigation and warned that the University of Chicago Press had opened itself to potential liability. It argued Bolnick lacked the credibility to lead any investigation into Pruitt’s work, referring to him as one of “the primary architects of the #pruittgate campaign” and accusing him of repeatedly and improperly using his role to target Pruitt and spread misinformation. Bolnick paused the investigation while they considered their options.

Iassumed it was unusual for academics to engage legal representation when confronted with a retraction or correction, but I was wrong. It turns out the process is incredibly messy, which perhaps isn’t surprising given that multiple reputations are often on the line. Things can become tricky when some authors want to retract and others don’t, putting the journal in the centre of a dispute between colleagues over data. “The journal has to adjudicate and give some sort of weight to one side or the other,” says Laskowski. “And I think they really don’t like doing that.”

One reason journals don’t retract more papers is related to the threat of litigation from an implicated author. Francesca Gino, a researcher at Harvard Business School who studies dishonesty, was recently the subject of an internal probe that found she had manipulated data used in multiple papers and recommended she be fired. Last August, she sued, for $25 million, both Harvard and a trio of data sleuths who run the blog Data Colada. (The suit has since been dismissed.)

But there are other reasons too. If none of the paper’s authors are willing to co-operate, the review process is often delayed. Or perhaps an author who was willing to fabricate data to have a paper published might also be willing to fabricate the requisite explanation. And the prospect of retractions can represent a credibility issue for journals—as well as for some of the ecosystems of academics and institutions that support them.

It can be hard to find the locus of integrity when it comes to academic publishing—it’s a system that benefits from looking the other way. Some academics are happy when papers are published even when those papers have errors; journals might prefer to avoid retractions that could cast aspersions on their evaluation process; and universities sometimes bury details about misconduct to avoid seeding doubts about their prestige.

Bik uses the analogy of running late for an appointment but getting caught for speeding is unlikely. “There are rules—it’s just very easy to ignore them.” As of this September, Oransky estimates, journals should be retracting at least ten times the number of papers presently being retracted.

Bolnik resumed his investigation in August 2020. He soon discovered that he and several of Pruitt’s co-authors and other journal editors had also been subject to a Freedom of Information Act request by Pruitt, who appeared keen to review their emails. Pruitt was given a chance to offer his rebuttal, but the retractions of many of his papers moved forward even as he refused to sign on to some of them.

Laskowski, relieved to have her papers with Pruitt retracted, says she was interviewed by McMaster several times and that she found the investigation thoughtful and diligent. By autumn 2021, McMaster had completed its investigation, and Pruitt was placed on administrative leave. Laskowski says she was told that Pruitt would be given a chance to respond. In early 2022, she received another update to inform her that McMaster was pursuing a termination hearing against Pruitt, who was tenured. The university informed her that she might be required to testify at the hearing on June 29—a date she remembers clearly because it’s her birthday. Laskowski agreed to meet with the university’s legal team ahead of the hearing in order to prepare. She was stressed and terrified.

However, Laskowski didn’t end up having to testify—instead, she got an email from McMaster’s lawyers telling her the university had reached a settlement with Pruitt. The details were confidential, but Laskowski was reassured that Pruitt would not pursue legal action against her for participating in McMaster’s investigation process. She has since wondered if Pruitt, now a well-established thorn, was paid a pile of money to simply go away. In May 2023, McMaster finally released the key findings from its inquiry, concluding that Pruitt had engaged in data falsification and fabrication involving eight papers—though more have been retracted or corrected. Pruitt’s doctoral dissertation at the University of Tennessee also appears to have been withdrawn (though the university declined to comment on the situation in 2021).

Pruitt’s new life reveals few signs of bruises. His Instagram suggests that he moved to New Orleans, where he was “adopted” by a spiritual community, crafts rosary beads in bright colours, and posts a large number of tank-top selfies. He reportedly found work teaching science at a Catholic high school and has more recently refashioned himself as a fantasy writer. His first novel, The Amber Menhir (book one in The Shadows of the Monolith series), is about a secretive society of magical scholars tasked with saving the world from a destructive celestial body known as “Calamity.” In the fall of 2024, it had 3.66 out of five stars from twenty-nine ratings on Goodreads, where the reviews ranged from “excellent dark fantasy” to “solidly okay.”

In an undated blog post entitled “The Way Forward is to Accept Your Part,” Pruitt offers a tepid mea culpa for his “Shakespearian” downfall. “McMaster University had to decide on the balance of probabilities (49/51%) whether these data duplications were deliberate, and they reached the conclusion that in eight papers they were,” he writes. “If I could have explained it adequately, then I wouldn’t have been found guilty.” Blaming his “data irregularities and time-keeping oversights,” he offers an apology. But he leaves the door open more than a crack. “Believe me when I say that there are two sides to this story,” he writes.

While Pruitt seems to be moving on, his former colleagues are left to speculate. Pruitt was incredibly smart, and it was clear to anyone who engaged with him that he was more than capable of doing the work he fabricated, of earning his accomplishments rather than stealing them. It’s possible that he would have produced papers with less sexy results—sexiness involving spiders perhaps already somewhat relative. “My guess is that he is motivated by different things, by different rewards than I am,” says Laskowski, speaking slowly and carefully. “I’m legitimately interested in understanding why the fish that I study do the things that they do. I find that incredibly satisfying. I don’t necessarily know that’s what motivates him.”

While some read the Pruitt story as a cautionary tale of hubris and academic sleight of hand, others have looked for a silver lining. “One of the important things that happened in the Pruitt case was that the scientific community actually came together to do the hard work of figuring out what happened and also ensuring as little collateral damage happened as possible,” says Oransky.

Collateral damage was indeed limited for Laskowski. The retraction didn’t result in a catastrophic fallout for her; her colleagues believed and supported her and empathized with her. She was seen as Pruitt’s victim rather than a co-conspirator, and her fight for transparency was perceived as heroic. But in many ways, the personal betrayal has been tougher to grapple with. “Here’s someone I thought had my back, and it turns out I was just a pawn for them,” she says. “You feel like—I didn’t matter at all, did I? ”