In Toronto early one summer morning, I saw two workmen. They were replacing the old sign for a Vietnamese restaurant. One man stood at the top of a ladder. The other was below, looking up from the sidewalk with all the furious concentration of someone who doesn’t want anybody to get the idea that he’s not doing anything.

I’d thought of this restaurant as a new addition to the neighbourhood. But as I passed, I realized it wasn’t new at all. I’d been walking by it for years. I am old enough now to lose track of these things. Evidently, it was old enough to need a new sign.

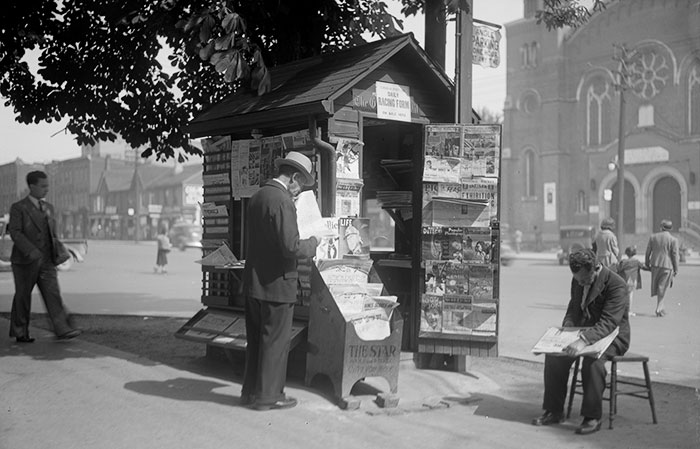

I like walking along Spadina on summer mornings. Later in the day, the wide sidewalks become so busy that, partly as a matter of navigation, I am preoccupied by the eddies of people around the Chinese stalls of live crab and bok choy, and the fruits I wouldn’t begin to know how to eat. But earlier in the day, I can entertain a longer perspective, and, as a result, the eastern sunlight takes on an antique quality. It’s possible to experience the jumbled streetscape in a way that’s not so different from how someone might have seen it while heading to Kensington Market to buy groceries on a summer morning in the 1940s.

Hotel Indiscreet

A seedy landmark adds colour to Spadina Avenue

Adrienne Kammerer

In the late 1990s, two men in dark suits showed up at Paul Wynn’s office. “They looked like something out of—what’s that movie called?—Men in Black,” says the proprietor of the Waverly Hotel, a Spadina Avenue landmark and, by his own admission, a “by-the-hour kind of place.” The gentlemen were “possibly from the US Justice Department or somewhere,” and they wanted to talk to him about James Earl Ray, the man who shot Dr. Martin Luther King. At first, Wynn thought to himself, “Is that a boxer or something? ” Rumour had it that Ray had stayed at the Waverly years before; Wynn put them in touch with the two “cute old Jewish guys” from whom he’d purchased it in 1984. The Waverly is one of Toronto’s oldest hotels, and the incident is just one footnote in its storied history. The punk band Black Lips is said to have dodged a falling ceiling in one of its suites. (“I’m not gonna say it’s not plausible… but bands don’t usually stay at the Waverly. They need to be down and out to stay at the Waverly.”) And the poet Milton Acorn lived there for years in the ’70s, frequently asking to change rooms out of fear that the RCMP was spying on him. Wynn says he has never heard of Acorn: “I guess that shows how culturally inept I am.”

—Amelia Schonbek

My list was in my pocket. I wanted to get to the cheese shop and the butcher and the fruit and vegetable stores before they became too crowded, and as I hurried past the busy man at the bottom of the ladder I could see that he and his partner were confronting a problem they had not anticipated. Behind the sign they were replacing, affixed to the brick facade, was the name of an even older restaurant.

The earlier sign, rendered in an old-fashioned cursive and a smaller art deco font, was made of tiles. They were a soft yellowish-green—a colour that conjures fedoras and sedans and soda fountains. The sign was mostly gone by the time I passed. Without a well-thought-out system for removing the old tiles, the man at the top of the ladder was prying them off one by one with a screwdriver and dropping them to the sidewalk.

I am not a historian. The Spadina Avenue of the 1940s is hardly the Peloponnesian War. But they are of equal historical interest—to me, at any rate. What that street used to look like, and sound like, and smell like, even a mere seventy years ago, seems as mysterious as Thermopylae.

“Mais, précisez, mon cher monsieur,” Marcel Proust is said to have pleaded when, after asking the English diplomat Harold Nicolson what it was like to attend the Conference of Versailles, the great novelist received a brisk summary of diplomatic manoeuvring. This was not what interested him.

Proust wanted details. He wanted to know the shape of the inkwells, the burnish of the desks, the smell of the starch on the delegates’ shirts, and the scent of witch hazel in their distinguished hair. He wanted to know what it was like to be there, then. He wanted to imagine precisely.

Maybe imagining is all that those who are not historians ever do with history. And perhaps all historians do is supply us with daydreams of the past. I doubt this job description would meet with enthusiasm in university history departments, but I don’t see this occupation as inconsequential—quite the opposite. What could be more important than showing us that our present is more than its hard, matter-of-fact surface suggests?

Historians gather what facts they can; and where the facts are equivocal, which is almost everywhere, they construct theories as carefully as an engineer constructs a bridge. They practise this discipline to teach us what every civilization needs to know: that time, like a wide, crowded sidewalk, is what we share with those we have passed and those who walk ahead of us.

Long ago, a young soldier raced across a battlefield, his chest bursting with fear and excitement and the exertion of running over uneven ground carrying his spear. And once, not so long ago, a waitress in Toronto poured a ten-cent cup of coffee for the first customer of the day. When I try to picture both individuals, I can’t decide whether it is the differences between us or our similarities that I find more consequential.

As I walked by, I wondered what stories had passed through the doorway under the art deco font of that yellowish-green tile sign—a sign that must once have been so familiar to the merchants and factory workers of the neighbourhood, it would have been almost impossible to imagine the block without it. What vast global histories could be deduced from the patrons who ordered the corned beef hash and ate the eggs and onion in that simple place? What revolutions and wars and cruel injustices had brought the first customer of the day to the counter? What was he thinking about—or worrying about, or daydreaming about, or remembering—while he drank his ten-cent cup of coffee? What headlines were written in the newspaper folded on the stool beside him, and what songs played on the radio on the corner shelf above the electric fan? And what, precisely, did the street look like, and sound like, and smell like when, having wished the waitress good morning, he buttoned his TipTop Tailors suit jacket, straightened his Rotman’s fedora, and stepped from that doorway into the angled summer light?

This is what I wondered as I walked down Spadina Avenue early one morning. And, as I continued on my way, I could hear from behind me the brittle sound of details being shattered, one by one, on the matter-of-fact surface of the present.

This appeared in the September 2011 issue.