Some poets need special tools to write. W.H. Auden relied on amphetamines. Edith Sitwell would lie in an open coffin. Amy Lowell chain-smoked cigars. For Vancouver poet Jordan Abel, it all rests on control-F.

Injun—one of three Canadian books vying for this year’s Griffin Poetry Prize, with the winner announced June 8—is built from a single Word document containing ninety-one public domain Western novels published between 1840 and 1950. Abel began by using his computer’s “find” function to track down specific words in the 10,000 page electronic file—the query for “injun,” for example, returned 509 results. He then copied and pasted the surrounding text, turning those sentences and fragments into verse. The terms that form the backbone of Abel’s work are typically drawn from the language of North American expansion. His previous book, Un/Inhabited (2014), manipulated chunks of American frontier stories into new configurations inspired by words like “discover,” “pioneer,” and “warpath.” However, Abel’s method is analog, too. He prints out his excerpts before scissoring them into new shapes. “Sometimes I would cut up a page without looking,” he writes, describing his process for Injun. “Sometimes I would rearrange the pieces until something sounded right. Sometimes I would just write down how the pieces fell together.”

From Thomas King and Lee Maracle to Katherena Vermette and Tracey Lindberg, Indigenous storytellers have enriched Canadian letters. But Abel does something quite different: Injun has no plot, no consistent narrator, no characters aside from vague notions of “injun” and settler (the term used for non-natives living on co-opted lands). Where Un/Inhabited focused on property and space, Injun focuses on language, on the loss of one’s comfort with some words, and the intrusion of others. Abel’s language may be pulled from early American pulp books, but the collection reads as a commentary on Canada’s colonial projects—namely the disruption, via the residential school system, of the passage of Indigenous language and knowledge from generation to generation.

None of this is said, mind: there’s no mention of residential schools, or of the potlatch laws that suppressed the traditions of the Nisga’a Nation, of which Abel is a part. The cut-and-paste construction is instead a savvy example of the “show, don’t tell” rule, moving white readers through a process of linguistic defamiliarization until their own language turns against them.

At thirty-two, Jordan Abel belongs to a group of rising First Nation poets (among them Liz Howard, Leanne Simpson, and Kateri Akiwenzie-Damm) who share a disregard for prior ages’—and the dominant culture’s—poetic rules. His signature cut-up technique was born out of what he calls “pure frustration.” An intergenerational survivor of the residential school system (his grandparents were taken and placed in such institutions), Abel grew up in Ontario, and did not meet another Nisga’a person until he was twenty-two. His only connection to Indigenous knowledge, therefore, was through the library. In 2007, he began exploring the work of Canadian ethnographer Marius Barbeau, who wrote extensively about West Coast Indigenous cultures, including Abel’s own Nisga’a Nation. The experience left Abel stymied: he was unable to translate his research into poems that adequately addressed the complexities of the subject matter. “Feeling as though I had no other options, I began erasing pieces of Barbeau’s book Totem Poles (1950) and hoping that there would be something there.” The result was his first collection, The Place of Scraps (2013), in which he created lengthy prose poems and pages of margin-to-margin text strategically erased to suggest borders and maps.

Injun is no less a personal project and no less ambitious. Like most conceptual work, the collection is best read in its entirety; individual poems, while compelling, benefit greatly from the context Abel creates for them. The book’s first section consists of twenty-six short pieces labelled a) – z), which contain words bracketed by superscript digits (such as “whitest1” and “frontier2”). The pieces start out tidy and restrained, but soon break apart and inch across the page. By “g)”, Abel has replaced the tight margins of the earlier poems with increasingly fractured syntax:

injuns in a heap

spring boiled9

over

lanterns buried

light against

day

old rifle old

trip

the

doubt outlasted

By “p)” the letters have begun to scatter, so that only a few words are discernible: bloody, teeth, scout, paleface, silvertip. In “r)” a reader has only a constellation of letters, single and paired, to work with, half of them upside-down; poems “s)” through “z)” are fully inverted. With the book inverted, “v)” reads (approximately):

i s ee

t he cl ear

m ad st rea m

bo di es

ar e

ma de

fr om t he we st24

b

r av e

chr is t ian tr ibes

c ampso f

ho st il e

hun ter s lea rni ng

t o lo v e

Here’s what it looks like when I read the book: I’m turning pages right to left by force of habit, then righting my path by turning pages left to right while reading them right first, then left. The effect is almost slapstick; the upside-down book is like some kind of dunce-cap, announcing that I don’t know which way is up. I may be an experienced reader of poetry, but I look like a buffoon.

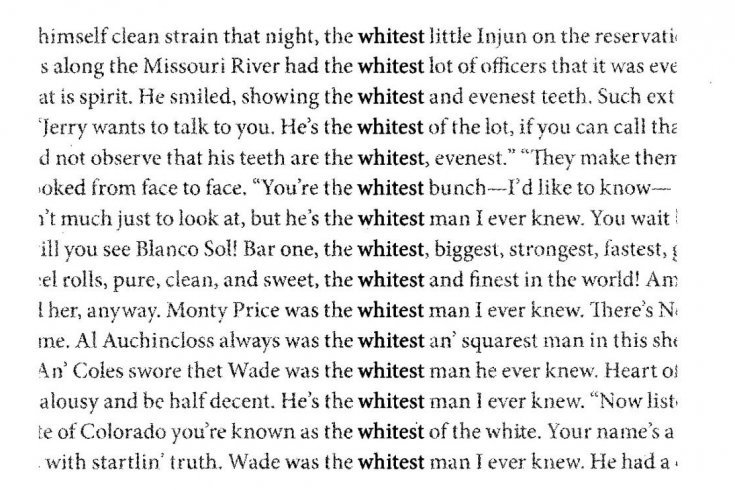

By Injun’s second section, “Notes,” I am able to right my book again, but the defamiliarization with language continues. For each of the twenty-eight aforementioned superscripts, Abel has compiled a corresponding entry; however, rather than clarify each word’s significance, “Notes” simply repeats the word in various contexts. The first entry, for “whitest,” begins:

himself clean strain that night, the whitest little Injun on the reservati

s along the Missouri River had the whitest lot of officers that it was eve

at is spirit. He smiles, showing the whitest and evenest teeth. Such ext

‘Jerry wants to talk to you. He’s the whitest of the lot, if you can call tha

Each poem is aligned so that the highlighted word forms a perfect column of black against the lighter grey of the surrounding text. The effect is like that of being in a room full of people speaking a language that is only somewhat familiar. Certain words stand out, but their meanings shift around them. The darker font suggests a sinister voice repeating certain words until they take up residence in the mind: squaw, bloody, scalped, redskin, half-breed. Visually, the formation looks like some kind of a monument. If these words and their connotations are ideas to be put to rest, Abel has created their graveyard here.

In the final section of Injun, deceptively and humbly called “Appendix,” Abel’s collection becomes wholly subversive. Abel presents the reader with a seventeen-page length of unbroken cut-and-paste prose, scattered with blank spaces. After struggling to fill in the blanks on the first page, it becomes clear that the missing word is always “injun.” Abel used the same technique in Un/Inhabited, offering the missing word as each poem’s title. Here, rather than supply the word “injun” from the get-go, Abel makes the reader dredge it up—“I seen a buck injun and his squaw,” “wash some of the injun smell off yuh,” and, “I want to drink with that ther’ injun killer.”

Abel erases the word, and my brain puts it back in. It seems significant that, in addition to being an added section of a text, the appendix is also a vestigial organ, one liable to rupture and infect a person from within. I feel as though I am trapped in the racist tirades of an endless, hate-filled online comments section:

“They’re s –

or there are s in the bunch,

at least,” he told them after a moment.

I saw an peeking

around the edge – to the south. “ s is

tricky –” I know s better than you do, Applehead. “Well, Lite, you

keep your sights lined up on that , then. But if there’s a

trick t’

git Luck, you KILL that .

I can’t help but feel a strong, deliberate subtext of “These are your words, not mine.” It is not just a rejection of colonial caricatures of Indigenous peoples, it is a deflection back on settler readers: this ugliness is mine to reconcile. Rather than tell a story of the loss of language through the residential school system, Abel picks English apart and flips it upside down so that we can barely grasp words that should be familiar. Rather than explain how settler Canadians are all complicit in the colonial project, he makes us repeat a racial epithet most of us would never utter out loud. For a reader who considers herself an ally of Indigenous causes, the process is disquieting, indeed, unsettling.

Canadian readers who consider themselves somehow outside of colonialism and all its hideous effects might be put off by being made to feel like the bad guy. There is no happy ending here in which we all just get along, no chalking the last centuries up to some kind of intercultural misunderstanding. Abel reduces the fiction of European virtue to its bare, racist sounds.