For countless generations, we Labrador Inuit have belonged to a vast coastal region of the Arctic and Subarctic along the Atlantic Ocean, now recognized as Nunatsiavut. For millennia, our ancestors have produced skillfully made, useful, meaningful things essential to our continued existence on this land. Over the last four centuries, as contact with the outside world increased, we also produced clothing, carvings, and other artwork for trade with the Europeans who visited our coast. Through these exchanges, Labrador Inuit objects made in the eighteenth, nineteenth, and early twentieth centuries can be found in museum collections worldwide. Yet in publications on modern Canadian Inuit art, Labrador Inuit artists and craftspeople are almost completely absent. Four living generations of artists have witnessed a dramatic time of transition on the Labrador coast. Their stories, memories, and knowledge, passed down through the generations of Inuit in our region, are little known outside of Nunatsiavut.

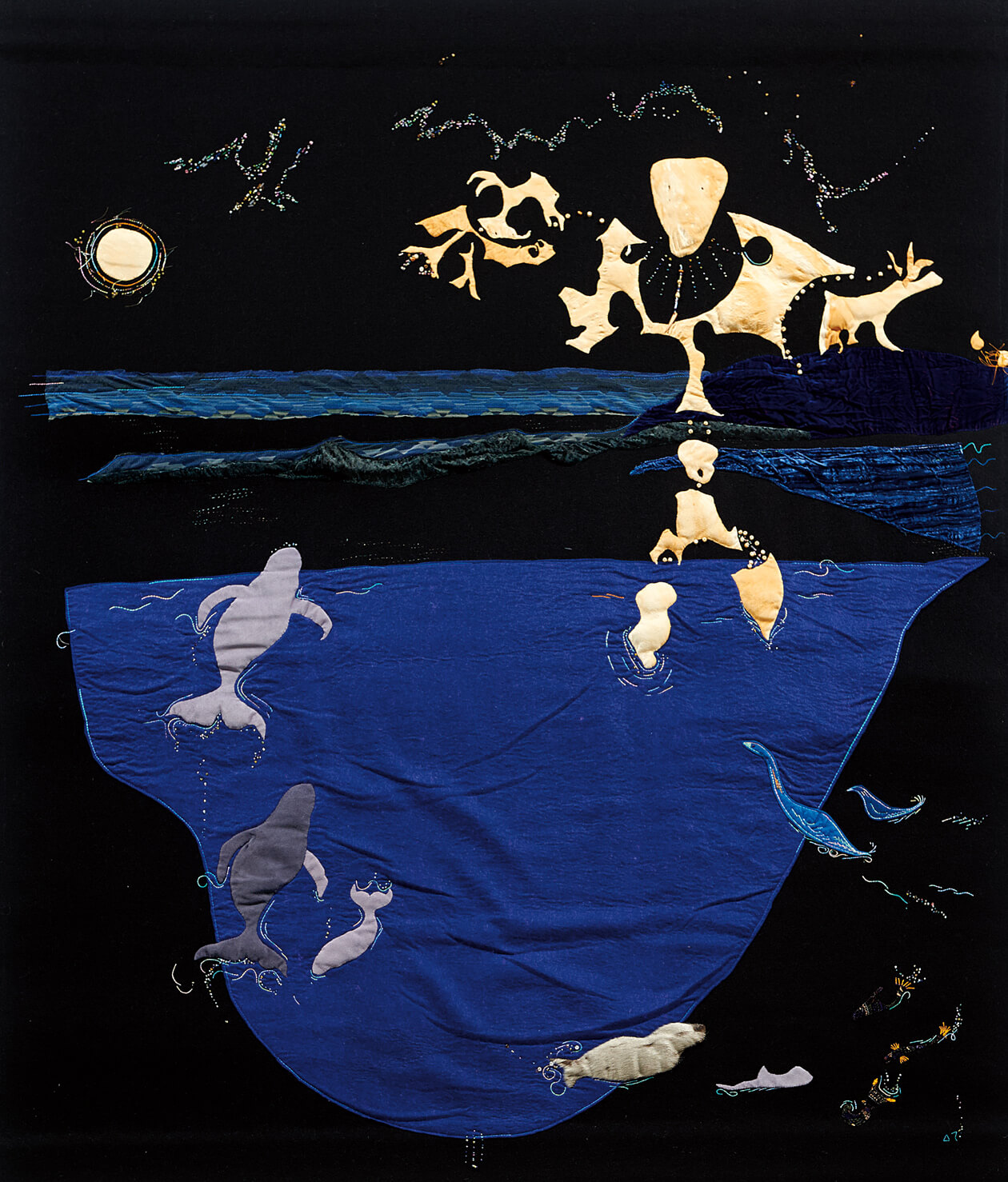

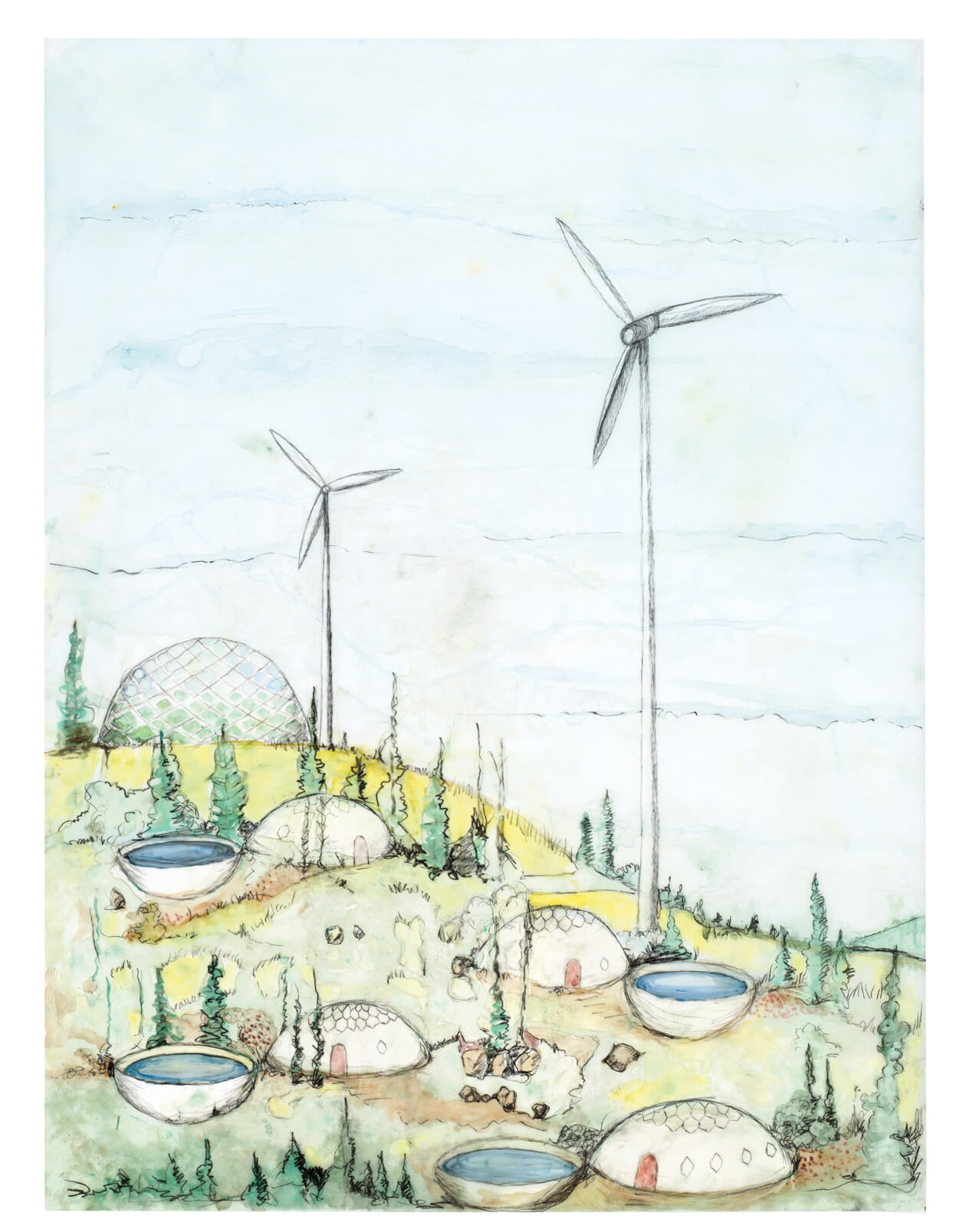

SakKijâjuk—meaning “to be visible” in the Labrador dialect of Inuktitut—presents a critical opportunity to introduce Nunatsiavummiut artists and craftspeople to the world. Through the work of four generations of artists—Elders, Trailblazers, Fire Keepers, and the Next Generation—this exhibition reveals the vital yet long-hidden art history of Nunatsiavut, highlighting the enduring resilience of our artists.

The artistry of the Labrador Inuit is evident throughout the entire historical record of the region, including the many centuries before European contact; contemporary visual arts are rooted in this rich and complex history. Unlike most other Inuit peoples who were geographically isolated until the early twentieth century, the Labrador Inuit have experienced more than four hundred years of prolonged contact with Kallunât. Whalers, fishermen, explorers, Moravian missionaries, and a succession of French and British colonialists exposed them to periods of exploitation, evangelization, colonization, and confederation. More recently, Inuit have begun to find their way out of that past, beginning with the Inuit political activism of the 1970s and leading to the realization of self-governance in 2005.

Yet while encounters between non-Inuit and Nunatsiavummiut have been well documented for over four centuries, and a number of excellent studies have been published from the related fields of archeology, anthropology, and ethnohistory, art historical literature is scant. Scholarly publications, museum collections, and exhibitions of Inuit art and visual culture have been noticeably devoid of Nunatsiavut content. Likewise, most seminal texts on Inuit art ignore Labrador completely, and only a handful of journal articles and catalogue essays deal with Nunatsiavummiut art in any depth or breadth.

Somewhat ironically, the main factor that led to the exclusion of Labrador Inuit art from the canon of Inuit and Canadian art history had little to do with the arts. In 1949—the same year that modern Inuit art exploded onto the international art scene, following a famously sold-out show at the Canadian Handicrafts Guild in Montreal—Newfoundland joined Confederation, but the new province’s government refused to submit to federal jurisdiction over its Aboriginal peoples. Elsewhere across Canada, the existing Indian Act and other legislation made the federal government financially responsible for the delivery of health, education, and other social services to the Aboriginal population. Yet when Newfoundland joined Canada, the two governments could not reach an agreement on who would be responsible for the Indian and Inuit populations. Instead, both Newfoundland and Canada decided against extending any federal considerations to the new province’s Inuit, NunatuKavut, Mi’kmaw, or the Innu Nation, in contrast to the rest of the country. The final version of the Terms of Union did not even mention Aboriginal peoples, and no provisions were made that would compel the Canadian government to accept full responsibility for the provision of social services to Newfoundland and Labrador’s Aboriginal peoples, as it did in the other provinces and territories across the country.

This political decision had the unintended effect of making Labrador Inuit artists ineligible to participate in any of the developments that emerged from the federally funded Inuit art initiatives advanced throughout what is now Nunavut and Nunavik. Since 1949, contemporary Inuit art has grown into a rich, varied practice and a respected field of study, as well as a multimillion-dollar industry; however, Labrador Inuit artists have remained nearly invisible within this history. While a handful of artists have found critical and commercial success on their own in recent decades, the understanding and recognition of Labrador Inuit art as a whole is still deeply lacking. In light of the dramatic advances in the field of Canadian Inuit art over half a century, the near-complete absence of Nunatsiavummiut visual culture from exhibitions and collections, as well as from art historical texts, is highly conspicuous.

Nunatsiavummiut have been considered less “authentic” than other Inuit, who lived in remote Arctic communities with little contact with the outside world. On the coast, our ancestors were not isolated from European settlers, traders, and travellers. They had contact with the Norse, Basque, Dutch, Spanish, Greenlandic, French, and English, who visited the coast as whalers, explorers, missionaries, trappers, traders, and government representatives. Instead of viewing our centuries-old history of contact, resistance, and exchange as a fascinating subject worthy of study, most Inuit art historians of the twentieth century have dismissed Labrador Inuit as too acculturated. The fact that many had converted to the Moravian faith contributed to this belief, although by the beginning of the modern Inuit art movement, Inuit peoples across the Canadian Arctic had been converted to Christianity. From the 1960s through the 1980s the commonly held belief was that Labrador Inuit had long been wholly assimilated into Kallunât culture, if they were thought of at all.

For Labradorimiut artists who wished to be given the same attention and respect as their peers across the Arctic, the perception of a separation between “authentic” Inuit in the 1950s Northwest Territories (as they were imagined) and the “inauthentic” Inuit of Labrador in the same time period has been an almost insurmountable barrier to success. When the Canadian and Newfoundland governments decided not to recognize the Indigenous peoples of the province, this lack of inclusion and federal recognition led many to believe there were no “real” Inuit in Labrador at all, and without funding to travel or communicate with the rest of the country, it was impossible for Labradorimiut to contradict this belief.

It wasn’t until the late 1980s that the first exploratory meetings between Labrador Inuit and staff from the federal government’s Inuit Art Section took place. During these meetings, for which curator Ingo Hessel travelled to Labrador, the Inuit Art Section offered to sponsor a survey of Labrador Inuit artists, and to this end they hired artist and then Ottawa-based university student Dinah Andersen to travel to each Inuit community along the Labrador coast and interview Inuit artists and craftspeople. Andersen completed approximately 140 interviews with artists and craftspeople who self-identified as Inuit during this trip, making this the first attempt to survey Inuit art in Labrador. The survey revealed that while our artistic traditions continued to thrive under the guidance of our elders and local artists, the major problem facing most Labrador Inuit artists was low earning levels resulting, in part, from a limited market. The survey also revealed shortages of art materials and adequate facilities in which artists could work. For example, houses on the coast tended to be (and still are) too small to allow indoor carving space, and many lacked running water, so carving could only be done outside in warmer months. As Dinah Andersen stated at the time, “For a young person interested in pursuing the arts on their own, it is next to impossible, not to mention discouraging.” Maria Muehlen, the head of the Inuit Art Section for the Department of Indian and Northern Affairs at the time, confirmed in Inuit Art Quarterly, “It is evident that artists in Labrador have not received a fraction of the attention given to NWT and Quebec artists, and the Inuit Art Section is eager to rectify this imbalance.”

Compounding this difficult situation, Inuit artists and craftspeople in Labrador were not allowed to use the “igloo tag” to authenticate their works as “real” Inuit art until 1990. Upon finally being granted this privilege, sculptor Gilbert Hay, who had been artistically and politically active in his community since the 1970s, remarked dryly, “After twenty years of struggling on my own to make it as an artist, the Government of Canada finally recognizes me as a genuine Inuk artist.”

Excerpted from SakKijâjuk: Art and Craft from Nunatsiavut by Heather Igloliorte. Copyright © 2017 by Goose Lane Editions and The Rooms Corporation of Newfoundland and Labrador. Reprinted by permission of Goose Lane Editions.