“Tough on crime” was at the centre of the Conservative platform throughout Stephen Harper’s tenure as prime minister. The Tories capped incarceration credit for pre-sentence custody, limited parole eligibility, opposed the modernization of obsolete marijuana laws, and legislated mandatory minimum sentences that overrode judicial discretion. As Ontario judge Melvyn Green wrote in a scathing assessment of Harper’s criminal-justice legacy, “a policy of punishment, incapacitation and stigmatization has replaced one premised on the prospect of rehabilitation, restoration and reform.”

Harper’s attitude toward criminals was so callous that even many Tory diehards began to push back. “The federal government has a simple approach to criminal justice: more people spending more time in jail,” lamented conservative National Post columnist Raymond J. de Souza following the federal government’s decision to shut down its prison-farm program. “When queried on the evidence for such measures or a broader philosophy of the role of incarceration in the criminal justice system,” he continued, “the justice department offers little more than slogans.”

Thankfully, Justin Trudeau’s Liberals have pledged to follow an “evidence-based” approach to policy-making—which could lead to the reopening of two Kingston-area prison farms. Shortly after winning power in 2015, the PM instructed justice minister Jody Wilson-Raybould to review the entire Harper-led criminal-justice reform agenda, with a view to “increasing the safety of our communities, getting value for money, addressing gaps and ensuring that current provisions are aligned with the objectives of the criminal justice system.”

One hopes this review will extend to the rehabilitation of high-risk sex offenders. When pedophiles and rapists are released from prison after serving a full sentence, they typically are treated as pariahs by fearful local residents (who often are riled up by local front-page tabloid headlines about threats posed by “pervs” and such). One of the few programs these men can turn to for help is Circles of Support and Accountability (CoSA), a Mennonite-founded network of volunteers formed in 1994.

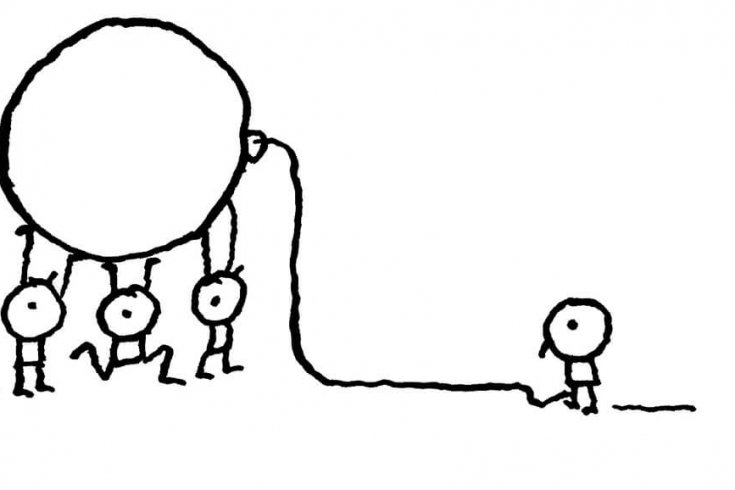

CoSA volunteers help these men deal with landlords, stay sober, access food banks, obtain government ID, avoid triggers that may cause them to reoffend, and cope with their guilt, shame, loneliness, and anger toward others (many sex criminals were themselves abused at an early age). When necessary, CoSA’s lay counsellors bring in psychologists, parole officers, or social workers to assist in rehabilitation efforts. The overall goal is to ensure that these men are not abandoned to their inner demons.

Studies suggest that CoSA interventions can reduce sexual recidivism by as much as 70 percent—which explains why the Canadian CoSA model has been adopted in the United States, Australia, New Zealand, and nations throughout Europe. And yet, in 2015, months before leaving office, the Tories cut most of CoSA’s funding—with the result that the group was forced to scale back or close down many of its operations.

The issue of how to stop predatory sexual behaviour is never far from the front pages. Yet this discussion too rarely includes any examination of the way we treat assailants after they have been caught, convicted, imprisoned, and released. Charlie Taylor and Wray Budreo are two infamous child molesters whom CoSA volunteers assisted in the 1990s. Taylor (who was mentally disabled) died in 2005. Budreo died in 2007. Both men endured the stigma of their horrific crimes until the grave. But neither man is known to have reoffended following his release from prison.

If our government is interested in “getting value for money,” it’s hard to beat CoSA. Because the army of CoSA volunteers that helps ex-cons is managed by only a tiny staff of paid coordinators, costs are minimal: between 2008 and 2014, total expenditures on CoSA operations coast to coast averaged only $2.1 million a year.

Last year, scholars Jill Anne Chouinard and Christine Riddick published a comprehensive evaluation of CoSA funded by Public Safety Canada and the Church Council on Justice and Corrections. In their analysis of CoSA’s value to society, they found that the cost of preventing a single “recidivistic event” (i.e., an act of abuse) within a five-year window is about $53,000.

Given all we know about the physical and psychic harm caused by abuse, does that seem like a large sum to spend on preventing a Canadian from being victimized by a released criminal? Surely, it’s one of the great bargains to be had. I’m guessing both Trudeau and Wilson-Raybould would readily agree.

This appeared in the September 2016 issue.