Tony Thompson has a very English name. He has a very English profession (butcher). With his tie, smock, and stolid frame, the fifty-eight-year-old shop-owner embodies a very English look. He works in a town outside London with the very English-sounding name of Romford, and speaks with a broad working-class English accent. He might well be the most English guy in England. And yet, paradoxically, he increasingly feels like he inhabits a strange land.

“Got to stop immigration,” he said when an NPR reporter asked him how he feels about today’s Brexit vote. “It’s only an island. You can only get so many people on an island, can’t you?”

Thompson insists that he is not racist, and notes that he has four mixed-race children. But he doesn’t believe that newcomers are good for the bottom line.

The Romford shop is not his first business. He once ran a meat counter in London’s East End. But then his white customers began moving out of the area, in favour of Muslim newcomers who disdained his (non-halal) meats. “That’s when I noticed a lot of change,” Thompson told NPR, “because my business went under.”

Most economists agree that the UK gains enormous economic advantages through its European Union membership. Companies can easily sell British-produced merchandise and service throughout Europe without enduring tariffs or customs inspections. They also can reassign workers from one European country to another, arrange visa-free travel, and submit to a single, unified set of regulatory standards on health, safety and consumer protection.

But Thompson doesn’t sell his meat to people in other countries. He sells it to customers who live around the corner. And you can’t blame him for objecting to immigration policies that cause England to absorb millions of people who reject his steak and chops as religiously impure.

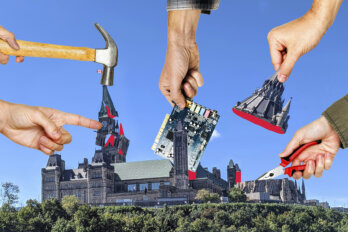

But even if Thompson could somehow be convinced that EU membership and open borders play to England’s overall economic advantage, it’s doubtful that his Brexit vote would be swayed. As in Canada during the free-trade debates of the Mulroney era, and in Quebec during the 1995 referendum campaign, these debates tend to come down to basic questions of tribal identity, not green-eyeshade arguments about profit and loss.

On an emotional level, at least, separatists, protectionists, and hard nationalists always try to present their tribe as vulnerable and besieged. Federalists and internationalists, on the other hand, present the world as warm and welcoming. They dismiss the idea of tribe as inherently bigoted; or ignore it entirely, and concentrate on abstractions such as per capita GDP.

In most parts of the world (Canada very much excluded), tribalists are now in the ascendant because the world seems like such a threatening place. Muslim refugees have poured into Europe from both east and south. Lone wolves are taking an ISIS-inspired slaughter campaign into Western population centres. In London, New York, Vancouver, and other large cities, foreign buyers are gobbling up prime real estate, while many native-born residents cannot afford any home at all. Real wages are stagnant, and working-class families have become downwardly mobile. Among some demographic groups, lifespans are going down, thanks to increased rates of suicide and drug addiction.

The most successful tribalists convince voters that they can solve all of these big, complex problems with emotionally satisfying one-off gestures of defiance against the liberal world order. Donald Trump’s plan for fixing US labour markets: Build a wall. Trump’s plan for fighting terrorism: ban Muslims. Trump’s plan for fixing America’s trade imbalance: tariffs on China. Trump’s plan for taming the currency markets: the gold standard. None of these policies make any more sense than a Brexit. But they at least offer the emotionally satisfying conceit that America can reclaim its wealth and dignity simply by shutting out the rest of the planet.

Tribalism is a powerful psychological force—deeply embedded in our brains through the mechanism of natural selection. But as recent history has shown, it can be overcome. Western Europe, once one of the most war-torn corners of the planet, hasn’t witnessed a major conflict in more than seventy years. In this regard, the European Union arguably stands—even more than the United Nations—as the single most important supranational body in human history.

Perhaps this is why many Britons take it for granted. Tony Thompson, the above-described Brexit-seeking butcher, was born in the late 1950s, more than a decade after the horrors of the Second World War had ceased. Unlike the men who created the EU, he has no direct personal knowledge of the devastation that can be unleashed when national populations succumb to tribalistic hatred.

The European Union isn’t perfect. Its heavy-handed regulations, in particular, are maddening to many Britons. And like all supranational bodies, it requires the surrender of certain sovereign powers—including the ability to fully control immigration flows. But the least that can be said for the EU is that it has helped keep man’s very worst impulses in check.

Let’s hope that a majority of Britain’s voters look past the local meat counter today, and take the long view on Europe.