On June 16, 2015, the House of Commons passed the Conservative government’s Zero Tolerance for Barbaric Cultural Practices Act, a masterful piece of legislation designed to recriminalize a great many things that are already illegal. The Act was aimed at preventing forced marriages, honour killings, and polygamy—which, needless to say, are bad and should not happen. The Tories claimed it was intended to help vulnerable immigrants and refugees. But it was really a nine-page dog whistle, pitched at the sort of people who are convinced the country is on the brink of Sharia law. The bill was introduced by (now-former) Immigration Minister Chris Alexander, who had previously advocated denying health care to refugees, and who had to suspend his (failed) re-election campaign following the viral spread of photographs of three-year-old Alan Kurdi laying dead on a beach.

The Act was a precursor to the Conservatives’ widely mocked “barbaric cultural practices” hotline, and a hint at the xenophobic campaign they went on to run. That day in the House of Commons, NDP MP after NDP MP stood up to speak against it. They pointed out, as many migrants’ advocates have, that the bill would wind up penalizing victims in addition to perpetrators (much like the government’s sex-work legislation), and that it was intended to paint the opposition as soft on violence against women. “This bill is part of the Conservative government’s pattern of introducing politicized measures that can actually cause harm,” the NDP’s Irene Mathyssen said.

As for the Liberals, this was an opportunity for the party to distinguish itself from the Conservatives—to stand up for the kind of open, united Canada that Justin Trudeau is always hyperventilating about. Surely they too would detail the many reasons to oppose the bill, to champion the tolerance and multiculturalism that Trudeau’s father is often credited with enshrining in Canadian law. Right?

“Our biggest problem is with the short title, ‘Zero Tolerance for Barbaric Cultural Practices Act,’” Liberal MP John McCallum said. “We moved an amendment to remove the word ‘cultural’ and the government refused.” Oh. Well, then. Trudeau and twenty-nine other Liberals voted yes, along with 152 Conservatives.

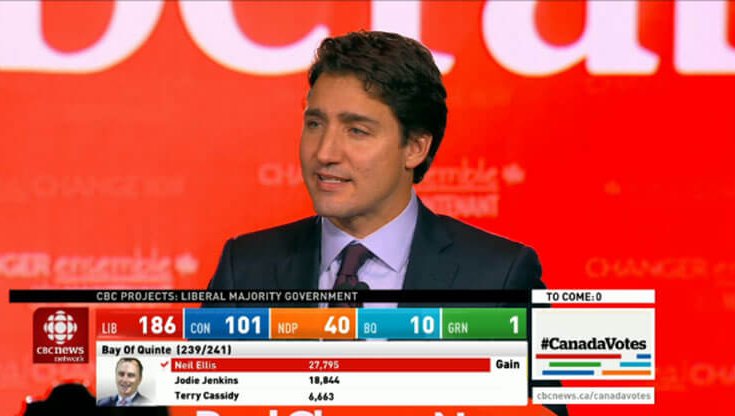

Monday’s election was a victory for everyone—that is, the majority of the country—who was put off by a decade of Stephen Harper’s petty, vindictive, obstreperous governance. His campaign combined the worst elements of the US Republicans, the British Conservatives, and the Australian Liberals. He lost, resoundingly, and that is no small thing. There is much to be welcomed about a Trudeau government: infrastructure spending and job creation; raising taxes on the wealthy and cutting them elsewhere; the legalization of recreational marijuana; and, perhaps most important, the symbolic end of the Harper years.

But it would be naive to consider this a win for the Canadian left. In addition to supporting the Barbaric Cultural Practices Act, the Liberals also toed the line on Bill C-51, the Tories’ rightfully maligned anti-terrorism law. (For a thorough analysis of C-51, read more here.) As Liberal candidates knocked on voters’ doors, it was fascinating to see them tie themselves in pretzels to justify their support for such a far-reaching threat to privacy and civil liberties. (They have promised to amend it, while the NDP swore to repeal it.) Their explanation boils down to: Trust us. “We’re the party of the Charter,” Liberal MP Adam Vaughan said last night on CBC, as if that were enough—and as if former Toronto police chief Bill Blair, who presided over the largest mass arrest in Canadian history, had not just been elected in Scarborough Southwest under the Grit banner.

After nine years of Conservative rule, the pre-Harper era might seem like a golden age. But the Chrétien-Martin years hardly represented a progressive paradise. As even Conservatives will gleefully tell you, the 1990s Liberals slashed federal spending, cut corporate tax rates, and wreaked long-term havoc on the Canadian welfare state. “Of all the neoliberal parties during the Clinton-Blair 1990s, the Liberal Party of Canada qualified as the neo-liberaliest,” David Frum wrote on theatlantic.com this week. It is possible, as Frum argues, that Trudeau will govern differently, but the historical record is not hopeful. With a majority government, and with the NDP reduced to forty-four seats, the Liberals will have little incentive to follow through on many of their most generous promises. Trudeau’s pledge to end first past the post in favour of a more representative system, which would benefit smaller parties like the NDP at the expense of larger ones like the Liberals, is probably already in peril.

Which brings us to the NDP. Thomas Mulcair has moved the party sharply to the centre, a strategy that appeared to pay off at the beginning of the long campaign but ultimately failed. In a bid for mainstream electability, the NDP opened up so much space on its left flank that the Liberals were able to occupy it—and cruise to a huge majority. This should not have happened to the party of Tommy Douglas, who was so often a thorn in the side of Pierre Elliot Trudeau. The NDP lost many good MPs last night, likely due to strategic voting: Megan Leslie, Andrew Cash, Peggy Nash. They all deserved better, of both their party and their constituents. But the NDP brought this on itself. After Andrea Horwath’s similar provincial failure in Ontario, one hopes the party has gotten the message.

It would be easy to dismiss such critiques of the Liberals as cynical and premature, but this is precisely the time for progressives to be vigilant. As Scott Reid wrote Tuesday in the Ottawa Citizen, now that he is in power, Trudeau may be tempted to cling to many of the uglier aspects of the Harper decade: the scorn for the press, the centralizing of control in the Prime Minister’s Office, the partisan low blows, the flouting of electoral laws, the silencing of the public service.

The euphoria surrounding Harper’s defeat is understandable. He was an easy man to despise, almost cartoonishly unlikeable. But the hard work comes in holding accountable a party with softer edges, a man less immediately repulsive. The hard work comes now.