On US Thanksgiving, a man I met on the streets of Ferguson, Missouri calls to invite me to a small church in nearby St. Louis. I am about to experience home cooking for 100 people, meet a troupe of singing activists from New York City, and observe a night of direct action that will disrupt Black Friday shoppers at four big box stores.

I arrive at St. Luke A.M.E. Church, a small building about ten kilometres south of Ferguson, as the sun is setting and the cool air is beginning to bite. The front door is locked and the chapel lights are off, but a tall, bearded fellow appears from the side of the building and greets me. This man, who calls himself Outlaw, chats me up about policing in the area. “You hungry? ” he offers. “We’ve got plenty to eat downstairs.”

The church basement contains several round tables. I find about fifteen people there, some already dining on turkey, potatoes, cornbread, and string beans. Three boys in matching striped shirts and close haircuts play Uno, Hide and Seek, and I Spy in rapid succession. As others arrive, I notice that everyone seems to be greeting a short, bespectacled black woman in a white chef’s coat. She introduces herself to me as Mama Cat.

Cathy “Mama Cat” Daniels, I soon learn, has been organizing meals like this for months. Her aim is to nourish, comfort, and strengthen those who are rallying against the August 9 police shooting of unarmed black teenager Michael Brown. Earlier this week, a grand jury’s decision not to indict Brown’s killer, Ferguson police officer Darren Wilson, provoked new protests, riots, and the subsequent deployment of National Guard troops into the area.

“I believe that you can fight a better fight when you’re well taken care of,” Daniels explains to a group of reporters in the chapel. “A hundred and eleven days ago, none of us knew each other, but today we are family.” As she addresses us, more and more protesters file into the basement. Soon the space is jammed with at least 100 people. It’s a multi-ethnic, multi-generational gathering, with food for all.

The meal begins in earnest after a group prayer. The basement fills with laughter and chatter; some young men improvise music with their voices, a piano, and snare drum. Media are asked to keep a respectful distance during this time, so I ask a man who I’d noticed standing near Daniels if he will speak to me outside.

Pastor Henry Logan and I take refuge from the increasingly cold night in his car. For the past two years, he has served as an associate pastor at the Friendly Temple Missionary Baptist Church, where Brown’s funeral was held. “Before Mike Brown, I would have never, in my mind, been doing any activism. I was always behind the pulpit. After Michael was killed, I don’t know what is was about this particular movement, but I just felt this major pulling that I needed to be out here, lending my voice and my feet,” the thirty-year-old preacher says in a rich, even baritone.

“There was something about this case that caused people to become quite fed up with what we have now, unfortunately, known as the norm. We will no longer accept this as the norm.”

Although he never met Brown, Logan knows his mother, Leslie McSpadden, who attends his church. In fact, he was standing beside her on Monday when she learned the news that Wilson would not face any criminal charges related to her son’s death. “They said [McSpadden] would get advance notice, but she didn’t…she found out at the exact same time the protesters found out,” he tells me.

I anticipated a church service would follow the meal, but as the tables clear, it becomes clear that many here are preparing to leave immediately. None will say where they are going. Outside the church, I see a woman who I tried to interview earlier about to join a caravan of vehicles. I ask if I can ride with her and two companions; she hesitates before ultimately saying yes.

We roll along a highway listening to a rap station on the radio. “Ready or Not” by the Fugees comes on, but I’m not ready for whatever is about to happen. I ask the passenger sitting next to me if I should take my camera once we get where we’re going. “Take all the equipment you need,” he replies.

After about twenty minutes of driving, we arrive at a Walmart. Although it is Thanksgiving, many retailers have opened this evening to entice shoppers with early Black Friday promotions. When my companions and I enter around 8:30 p.m., the massive store is bustling. As we mill around, I recognize many faces from the church basement. It seems most of the younger folks are here.

Suddenly the woman who drove me screams out, “Hands up!” Instantly the chorus of protesters replies, “Don’t shoot!” As they begin chanting, wide-eyed customers freeze and stare. A few actually run away; others pick up the cry and begin to shout along. Many people pull out their phones and begin recording the scene.

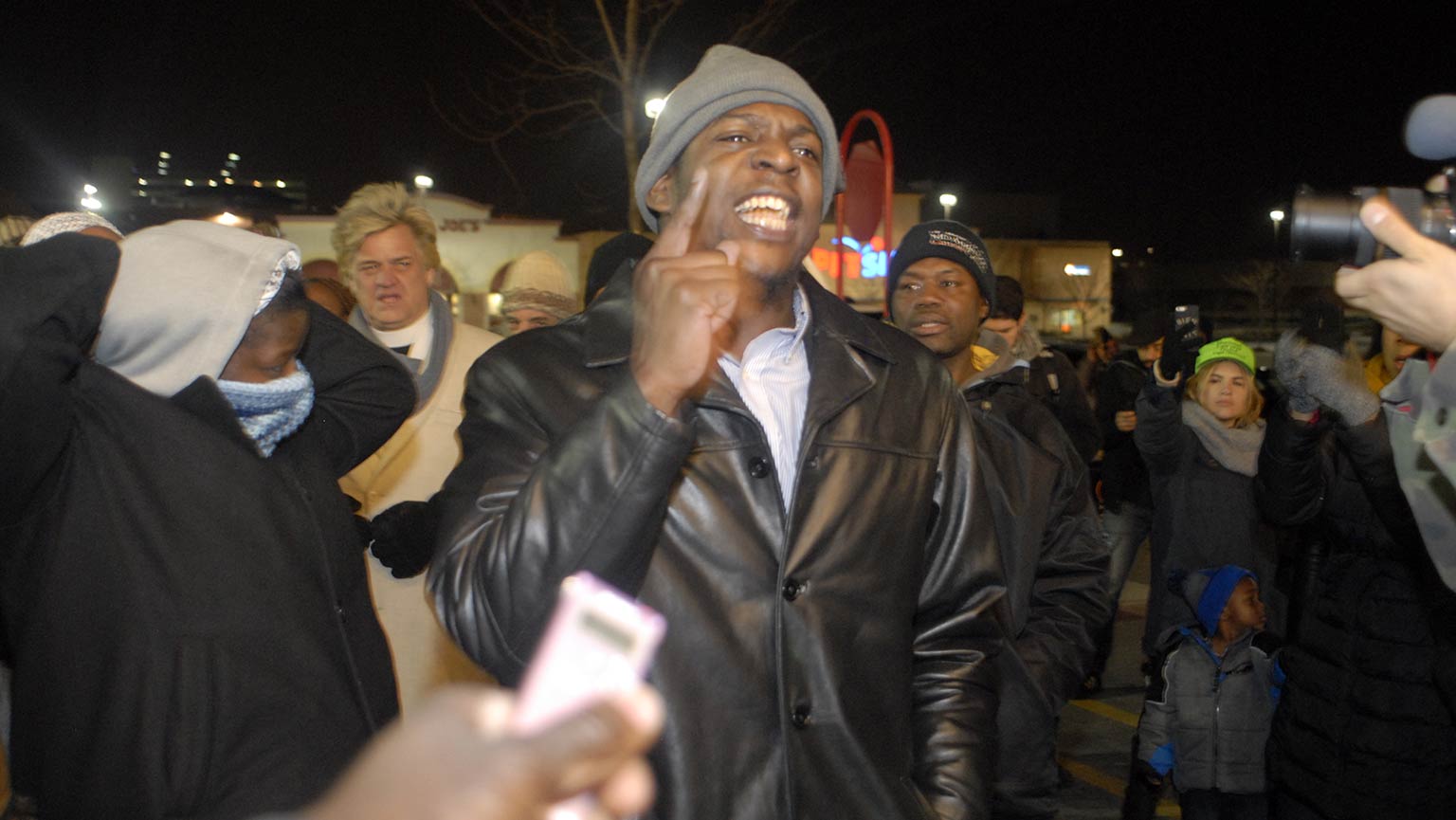

The protesters don’t linger long. They march, chanting and singing, toward the exit. Some curious customers actually follow them. Paid-duty police officers (presumably hired to keep order among shoppers, not demonstrators) trail the group with stern faces. Just outside the exit, the group of about fifty protesters turns to face—and chastise—the police.

“You will be arrested for trespassing,” an officer tells a protester. “Go arrest Darren Wilson for killing Mike Brown!” he thunders back to her. People around him begin chanting, “Who do you protect? Who do you serve? ”

This group includes a crew of singing activists from New York, who have joined in after engaging in a protest at the nearby headquarters of agri-business giant Monsanto. They sing “Which side are you on? ” and “Justice for Mike Brown” in harmony. After a general trespass warning from a police bullhorn and several angry rebukes from a clearly rattled group of cops, the demonstrators finally disperse to their cars.

Within minutes, we’re back on the highway headed for another big box. Over the next few hours, the group hits two more Walmart outlets and one Target. Each time, they begin pretend to shop before chanting; some even fill up carts and baskets. And each time the protest starts, customers are variously startled, intrigued, or upset.

The choice to target Walmarts may extend beyond its popularity as a Black Friday shopping destination. On August 5, four days before Brown was killed in Ferguson, a twenty-two-year-old black man named John Crawford III was shot by police inside a Walmart in Ohio, presumably while he was shopping for an air rifle. A grand jury in that state chose not to lay any criminal charges against the white police officer who killed him.

Dan Wam, a young man with blond hair and glasses, watches the demonstration outside of Target with a friend. “I think the more places they can get, the more people they’ll touch,” he says. “I don’t know how effective being at Target is, but it’s coming from a good place.” Tonight is his first time witnessing a protest in the flesh. Before now, he admits, he’d been “sucked into the livestream world,” watching from afar on his computer.

By the time the protesters reach their final destination, the third Walmart, the police stationed there seem to be on alert. Officers are congregated close to the door, eyeing everyone who enters—though they dare not impede potential shoppers. When the chants and songs break out, police warn that demonstrators who don’t leave in two minutes will be arrested. As they follow the marchers out, I notice one officer filming people with a camcorder.

Twenty-eight police officers form a line outside the store. One commands the others to move forward and push the agitators back. One of the men in the front of the protest group is pastor Doug Hollis—he is a cousin of both the late Brown and Vonderrit Myers, yet another eighteen-year-old who was shot and killed by an off-duty police officer in St. Louis on October 8.

“We’re not looters, we’re not thugs,” Hollis says to the line of police, his voice raw from shouting. “We’re pastors, we’re preachers, we’re US citizens.” The group behind him calls out in agreement after every one of his phrases. This is the church-like call and response I expected to hear tonight, although not in this dramatic venue. “You don’t have to touch us,” Hollis tells the cops, “and we’re not going to touch you.”

Afterwards, my driver, who calls herself Sojourner, at last agrees to an interview. I ask how she feels after engaging in these direct actions. “They didn’t expect it,” she says with a smile. “People have to be creative—be angry, but be creative.”

Sojourner, who is in her mid-twenties, says she has lost her fear of police since she joined the protests about Brown’s killing: “Once upon a time, I would be afraid that I would get in trouble,” she tells me. “It’s so different when you’re standing up for your rights and what you believe in.”