The smooth corporate face of the National Football League can be best seen in the machinelike perfection of the New England Patriots. Their silky quarterback looks like a model, dates supermodels, and commands the most efficient offence in the league with a relentless, minimalist style. His unmarked, preternaturally blank face shows little response to the violence swirling around him. His dominant blandness seems the very paradigm of the modern game. But for all his winning ways, the quarterback and his on-field campaign have become only the tail that wags the dog of the NFL. The real action lies elsewhere.

As the American empire experienced its comeuppance in the jungles of Southeast Asia, American professional football was coming into its own, taking over television, magazine covers, and the national consciousness. The NFL was a metaphor festival on cleats, and the first metaphor out of everyone’s mouth was that it was America’s game, America incarnate: knock the other guy on his ass and take his land. Underlying that was the more primal metaphor: war. The game was so perceived as America’s sublimation of war that novelist Don DeLillo took on the culture of football in his early-1970s novel, End Zone. His protagonist studied nuclear megadeath as he played college ball on scholarship. As one professor said, “I reject the notion of football as warfare. Warfare is warfare. We don’t need substitutes because we’ve got the real thing.”

Only America didn’t have the real thing. Vietnam—the war being fought and ending as the NFL rose to dominate American sports consciousness—offered no component of knocking the other guy on his ass and taking his land. The war for which the NFL was a metaphor was the only war America dreamed about or trained for, a showdown with the Russians on the plains of Europe, tank on tank, grunt on grunt. In that longed-for war, you could actually see a guy to knock down, and that guy had land you could actually take. It would be just like football.

In Oliver Stone’s NFL film, Any Given Sunday, the war has been internalized. Coaches are depicted doing battle with their own dicks; impotence is presented as a consequence of wresting wills with younger, indestructible Hectors and Herculeses. For the warriors, the game seems merely a hiatus in the non-stop orgy of sex, drugs, and weightlifting that comprises a modern player’s life. But not even Stone, always fascinated by the glamour of violence, can capture the visceral, deranged action on the field.

The barbarity, the carnage of pro football, is so addictive on your TV because it was perfectly scaled to fit there, courtesy of PR genius Pete Rozelle, the NFL commissioner who built the game through an iron-fisted branding strategy. One of Rozelle’s strongest legacies was sizing the coverage to the parameters of a TV screen and making the networks do it his way. You couldn’t disconnect from an NFL game if you were on heroin. The camera is in a better position than all but the very best seats, and when it’s time for action there are few fans visible: it’s just you and your game. Yet watching a game is not unlike being on heroin. The action passes by in a haze, moments are undifferentiated, a narcotic gloss seems to lie between you and the onscreen experience.

The league, recognizing that a younger generation suffers from a kind of ennui, has now hung cameras on wires that traverse the game at swooping angles. The shots offer initial excitement, but after a few games it becomes clear that the NFL severely limits the use of its one cool technology. The overhead wire-flying camera only shoots from angles that perfectly mimic the composition of the NFL video games. The league has so little faith in its own product it deliberately presents the reality of football as equal to an artificial, fan-manipulated fantasy.

We watch football, however narcotized, mostly for three reasons: the beauty and grace of the long pass and reception, the thrill of seeing a well-paid genetic freak get his brains knocked out, and to visit or witness a final frontier, which was just being revealed to a broader America as the NFL broke large. It is a frontier so seductive and esoteric that when Don DeLillo sought to capture it he wrote about “the mystery of black speed.” African-American receivers of extraordinary grace and strength were bringing the long ball to the game by blazing past white defensive backs as if they were standing still. Speed seemed to be a talent no white player, no matter how hard he worked, could match. It seemed a gift from the gods, like physical beauty. Of course, the black speed demons worked their asses off to be fast, but in its first appearance, and in the colonial language used by sportscasters and the league to describe it, that speed was not presented as earned in the grind of weightlifting and running stadium stairs. DeLillo captured the awe and reverence pure speed could induce: “But mostly [a black running back] could fly . . . Speed is the last excitement left, the one thing we haven’t used up, still naked in its potential, the mysterious black gift that thrills the millions.”

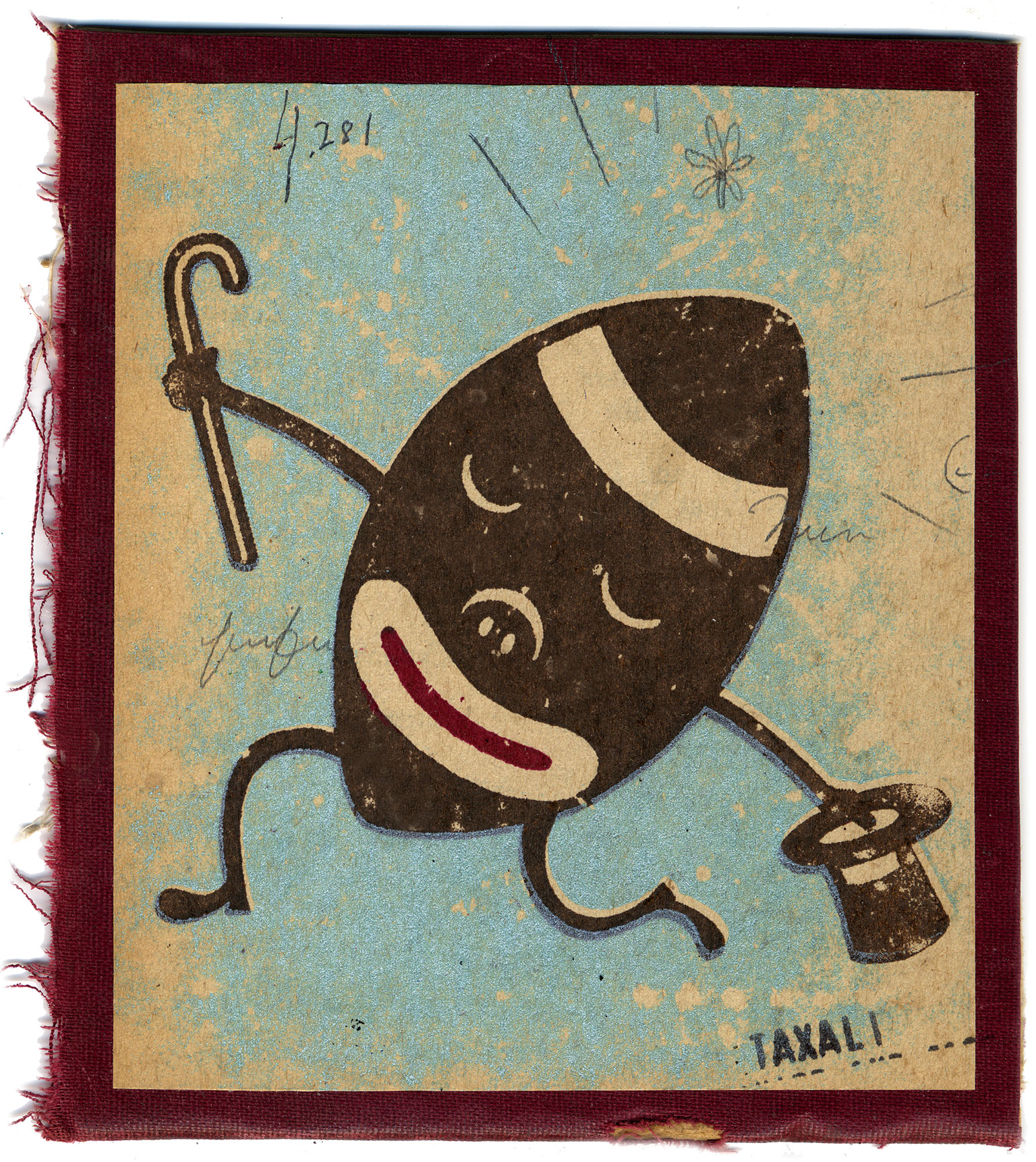

O. J. Simpson proved the most easily digestible icon of black speed—the least threatening to a white mainstream. His enormous face alight, O. J. moved with a magical grace. His acceleration from a dead stop seemed barely human, and he slipped past defenders as if they were ghosts. Unlike Jim Brown, the nfl’s first angry, unrepentant black god, O. J. smiled every time he knocked someone on his ass. And, unlike Brown, O. J. did not seek to cream anybody; he would rather evade, rather dance, rather elide than initiate collision. His team’s management colluded in the spectacle. They almost never fielded a team around O. J. that could win. Instead they built an offence that encouraged him to shine regardless of the outcome of the game. O. J. was a black yuppie, using his skills to move up as he consistently tried to prove he never really meant to hurt anybody. He became a sideshow, a kind of minstrel act: a smiling, contented, unthreatening black Superman, happy to show off, make pals, and never taste victory.

The NFL marketers had need of a minstrel show, a black yuppie, because, along with blazing black speed, post-Vietnam the NFL saw black anger surface with a sanction it had in no other sport, because the NFL thrives on anger, masochism, and the will to hurt.

Psycho star safety Jack Tatum of the Oakland Raiders embodied a new black street presence—the man home from Vietnam and from the civil rights movement who, in the lyrics of Townes Van Zandt, wore his attitude “outside his pants, for all the honest world to feel.” Tatum was the embodiment of the Black Panthers: snaggle-toothed, with a scraggly, outrageous Afro and heavy-lidded mack-daddy eyes.

He lived for lethal impact. He hit people so hard you could see their skeletons right through their skin, every joint and bone, like a cartoon. And when Tatum launched himself like a black bullet and cracked someone, the middle-aged white men on the sidelines who ran the game nodded, thrilled. They’d never seen a white boy who could hit like that, and here was urban black rage contained on the ball field, catharsis with a capital C.

Tatum’s persona reflected the uneasy fascination and dread with which a larger white audience experienced the urban black man, a fascination and dread later reflected in the rise of urban hip hop and its attendant mythologies. This complex, tragic, epically multi-levelled and self-contradictory obsession drew the white audience deeply into football. Tatum swaggered, and would happily blow his own coverage, give up a touchdown, for the chance to mutilate someone with a tackle.

It dawned on the league office that having guys get hit so hard their skeletons showed through their skin put a team’s short-term physical assets (the players) at risk. The teams that didn’t have a Jack Tatum complained. And nobody wanted a repeat of poor Darryl Stingley being taken off the field paralyzed after Tatum clobbered him, a reminder to the fans of the actual level of carnage being perpetrated for their kicks. Nor did the league want a brand dominated by black style or identity. So, after putting that style at the forefront of their marketing—House Negro O. J. Simpson and Field Negro Jack Tatum proved the Scylla and Charybdis of brand identity—the league fuelled its white fans’ love-hate relationship with black athleticism by suppressing its more flamboyant aspects.

Thus the NFL’s penchant for right-wing micromanagement began its inexorable march to tame the game’s aesthetic. After years of being celebrated, certain hits were outlawed. And so was black expression. Over the decades, every conceivable style point has been banned: personalized do-rags, prolonged end zone dances, elaborate post-touchdown stunts, and even players celebrating with unison dancing.

In suppressing the style, the league sought to suppress its underlying substance. That substance was specific racial identity expressed in ultra-violence, and public jubilation at its result. The league wanted the black genie back in the bottle. Jack Tatum didn’t mutilate in the name of black identity (as expressed by his hair, his headband, his don’t-give-a-shit-about-playbook freelancing); he now mutilated in the name of his team, the Oakland Raiders, which granted its players and fans an identity that transcended race and class. The league raced to market a key aspect of its identity—black and white men pummelling each other as equals, each trying the stereotypical virtues of their race in combat with The Other—before fans figured out that for them the game itself was secondary to the national identity crisis, a tableau of mutual racial loathing and admiration being played out on Sundays.

And yet what is the NFL afraid of? It’s not like the players, black or white, have any real power to affect the game, given their toothless union and injury-truncated careers. Few stick around long enough to generate bargaining power. So it’s not actual rebellion the league suppresses. It’s perceived brand damage—image rebellion. Brand control is a far more desperate struggle than a style or culture clash: it’s war over who controls perception. For all the NFL’s suppression of the putatively Bad Black Man and his excessive style, they heap praise and extra visual attention on the Good Negroes who celebrate Jesus with fingers thrust into the sky after every moderately decent play. The networks collude in this aspect of brand management by making sure those fingers fill the nightly roster of highlights. Here the league showcases racial unity: both black and white are encouraged to point to the Lord with no fines or sanctions.

The NFL of the early 1970s moved from a half-knowing metaphorical existence that poetically represented America’s dilemma of a genuine war and violent racial frustration, to a smoother, more harmonious 1990s America. In that harmonious fantasyland, black and white sportscasters stood side by side and smiled in harmless rivalry, as only true equals in a truly equal society might. And the style of the game echoed this new, bland paradigm.

The careful, slow winnowing of any style save that approved by the corporation is a stealth process that’s helped the NFL render itself tragic. By refusing to allow spontaneous outbursts or individual totems, the league has systematically culled the joy from the violence. The NFL wants to show only the nine-to-five of its brutality, never the ecstasy accomplishment brings. As with any individual who acknowledges only work and pain, the league is at war with itself. In removing decoration from the orderly game procession up and down the field, the league has slowly leached itself of metaphor. And a soul without metaphor has no poetry.

But if you close the doors, they’ll come in through the windows; however the league denies its own metaphors, they still rise to the surface. The most potent lie in the bodies of the players themselves and how the changes in their bodies have altered the game and their careers. NFL football players, through year-round training, diet, and steroids no doubt, have grown so large and so fast that the human body can no longer sustain the impacts they generate. The collisions are too destructive. By pursuing excellence, NFL players have sown the seeds for their own destruction in an age when injuries are increasingly severe. No wonder the league doesn’t want celebration when one player wipes out another. Yet even this produces a metaphor.

The new body image in the NFL is the natural end product of an obsession with size and the new gargantuanism on display at any shopping mall. It can also be read as another metaphor for America: its rabid consumption and growth to no purpose save self-injury. This new gargantuanism grew from America’s bodybuilding obsession. Rooted in that obsession is the death of the American Dream. Horatio Alger set the model: hard work brings success.

That bodybuilders are essentially deformed freaks speaks not only to the deformation of the American dream, but also the physical deformation of the NFL player. It raises the compensatory aspects of someone dedicating themselves to looking like a he-man to the point of caricature. A weightlifting obsession turns leisure into more work—a return to the oldest form of manual labour (picking stuff up and putting it down)—and the result of this new hard work is a body perverted into a form that no upper—or ruling—class figure would ever admire. The weightlifting body is a badge of futility: look how much of my own labour I put into this body, because I have no more productive manifestation of my energies available. Don’t you envy the discipline and pain of my pointless output?

The ideals of elegance, effortlessness, the long, lithe line that so incarnated upper-class style, were stomped upon in the name of the 250-kilo rack squat. True leisure-class Americans tried lifting for a while, but disliked the prole associations and turned to yoga, with its high-minded context, or Pilates, with its aim of creating the classical upper-class physique. Meanwhile, real athletes and wannabes pump that iron. NFL players grow increasingly enormous, their bodies ever more specialized for ever more specialized athletic tasks—the lineman body, the linebacker body, the cornerback body. Americans, not recognizing that their physical role models live in a limited, fantasy universe, emulate what they see on the screen.

Yet none of these are the essence of the tragedy of the NFL. Not the average death age of former players, not the wilful disfigurement of its athletes, the pointless repetition of the same athletic moments, the grinding of all players into certain archetypes, the suppression of black expression, or the inherent invisibility of the reality of the game. The larger tragedy is a loss of truth. In the old days, guys knocked each others’ brains out for a variety of reasons. The famously dreaded black defensive lineman David “Deacon” Jones’s remarks about being baffled by the emergence of black quarterbacks were deemed far too candid. Prior to the existence of black quarterbacks, Jones’s central joy lay in his freedom to legally maim well-paid, good-looking white leaders. With black men providing his theoretical nemesis, Jones was unsure of how hard to hit.

The NFL remains a league virulently in denial. The confrontations of race and violence are now suppressed into a stew of “the will to win” and “the love of the team.” Individualism is punished. More than any other professional league, the NFL has smoothed over the reality of its racial identity, the appeal of its core violence, and the effects of its own management style. This smoothing process has been aimed, knowingly or not, at every possible metaphor that might leak from the edges of corporate control. Rather than the skill or love of sport, the NFL is a non-stop exhibition of force marketing and amazing sports science. All this technique, all this pointless virtuosity, has erased any ragged edge. Football looks only inward at image—a game so slick that no room is left for character or narrative. And without a saga, all that remains is knocking the other guy on his ass and taking his land.