Courtesy of the Canada Council for the Arts

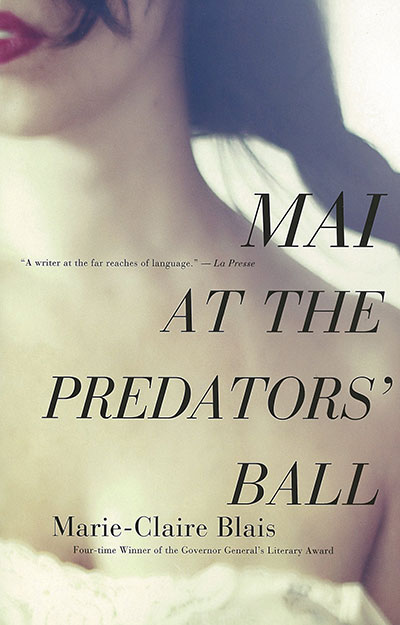

Courtesy of the Canada Council for the ArtsIn “How to Read a Masterpiece,” her 2009 article for The Walrus, Marianne Ackerman appealed to Nigel Spencer for help understanding the craft of Marie-Claire Blais, one of Canada’s most celebrated—and most challenging—writers. “Let it wash over you,” the veteran translator, author, and professor of English advised her. “Like body surfing, let the waves take you. Don’t try to touch bottom, and you won’t hit the rocks.” Spencer has translated four novels in Blais’s current cycle from French to English, and is now at work on her latest instalment, Le jeune homme sans avenir. This evening in Ottawa, he will receive his third Governor General’s Literary Award for translation—for Blais’s Mai at the Predators’ Ball (Mai au bal des prédateurs). He lives in Montreal.

You were born in England. When did you learn French?

In England, we had about half an hour of French instruction a week, so I had a lot of catching up to do when I got here in grade five. Maybe that helped me. French was always my best subject after that. Like a lot of anglophones in Montreal, I could write literary essays in French, but I couldn’t order a hamburger until I got a summer job where I had to speak without translating first. You know what it’s like if you’re learning another language—when you start dreaming or thinking in that language, then you know you’ve made it.

How did you get into translation?

I’ve always enjoyed fooling around with language. Way back in the early ’70s, I did some translations for my own pleasure; I think the first book was a manual on filmmaking. I translated some poetry, again just for fun—I found myself doing it in my head as I read it. Then, I read a play by Marie-Claire Blais called L’île. I enjoyed it, translated a bit of it, and sent it to her. She replied, “I really like this, but somebody is already working on the book.” She suggested some other things for me. And now we’ve made it to this novel cycle of hers.

Why were you drawn to Blais’s writing?

The way she plays with stream of consciousness and shifts voices, but makes the voices quite identifiable. I think that appeals to my sense of style and tone.

Can you describe the challenge of translating a 328–page book that’s written as just one paragraph, with maybe fifteen or thirty periods?

The sentence structure in English and French is sometimes radically different. When you’re dealing with a sentence that’s, say, fourteen pages long, it’s like taking Lego apart and putting it back together. Then, you’ve got to fix the joins and make sure that the voices transition and the inner and outer consciousness works. You change times, you change characters, and so on.

How do you work that out on the page?

I tend to put in a lot of commas and, sometimes, dashes. It’s a bit like scaffolding; it helps me sort out the pieces. Then, as I feel I’m getting the tone and the voices sorted out for the reader, I can start pulling out the commas to let it flow more smoothly.

What other obstacles do you encounter translating Blais?

With a francophone writer speaking about an American milieu, I was very afraid earlier, when I was doing some stories before these novels, that it was going to come out sounding American. It didn’t. You had that otherness, that vision of hers, which fortunately survived my translation.

What’s the relationship between translator and author like?

With Marie-Claire, it’s as though we’re walking parallel. We’re not holding hands, but we’re side by side.

And with other authors?

It depends. I’ve had authors who micromanage like crazy and, in some cases, overestimate their own knowledge of English. And it drives me up the wall. Now, that’s not just a matter of ego—I’ll admit to that too—but it’s also about feeling enclosed. Some freedom is necessary to do justice to the work —especially when it’s a matter of wordplay or jeu d’esprit. Marie-Claire leaves me a lot of freedom.

Off the top of your head, is there any word puzzle you are particularly proud of solving?

There’s a seminal story by Pauline Michel, which is really all about her and her career and her background. It’s called Une carrière de silence. She grew up in Asbestos, so there’s an obvious pun on carrière: it can mean quarry or it can mean her career as a writer. I had to work like hell, but I finally said This Silence of Mine.

What does it mean to win a Governor General’s Literary Award?

Some people claim to be a bit blasé. I’m not. I really get a kick out of it. Translating is a very solitary kind of thing, so to think somebody has seen this and somebody thinks it’s good—wow, phew, I didn’t screw up after all. There’s also a sense of “Oh, somebody noticed,” which is a big thing, especially for a translator.

Many people find Blais too challenging, even inaccessible. Why is it important we read her?

These books are about humanity. They really challenge us to stretch our imaginative and spiritual muscles. It hurts, but we have to do it, or we’re basically screwed as a species.

How does it feel to return to her world, once again, with Le jeune homme sans avenir?

I always feel a bit intimidated. It’s not easy. There’s an emotional tunnel you have to go through—it’s a bit like purgatory. Part of that is discovering the book as a reader who gets under the skin of it, probably in a way that almost nobody does except the author. So, there’s a certain amount of trepidation and then there’s a sense of exhilaration, thinking “Okay, here we go, it’s four, five months of adrenaline time.”

You can do the work that quickly?

I don’t think I could do it any other way. I’ve got to dive into that tunnel and work my way through. I get in gradually, as I’m doing now with Le jeune homme. And then, after the holidays, it’s going to be winter and I’ll be in the middle of the novel. For four or five months, there will be very little else, with all the risk to my psyche that that involves.

This interview has been condensed and edited for publication.