The boots were ankle high, smooth red leather Louboutins with crystal studs, on sale for $339.99.

“Buy them,” Tom told Salma, suffused with the generosity of the three local beers he had downed with his colleagues after a Health Informatics panel. “If you were ever to buy these boots…” They had wandered into a store called Bring Yer Sexy Bootz at an open-air mall in Orange County. Stamp-sized flakes of ash were drifting and settling from a forest fire in the hills nearby.

“They’re just that much too expensive,” Salma said, peeling the tight left boot from the arch of her foot. “If they were $319.99, I wouldn’t even think about it.” She sat cradling the smooth red leather and the glittering crystal studs without replacing the boot in its box.

“Will you wear them tonight?” Tom asked. “If I pay? ”

Salma didn’t nod or say yes. She just put the boots back in the box and let Tom take it to the counter and pay. That was how Salma became the prostitute of her husband. Later that night, as she was wiping sticky smears from her neck and chest, sitting down on the toilet to pee, she noticed that she was still wearing the red boots. They were fabulous.

Tom and Salma did not live in Orange County. They lived in Toronto, Ontario, Canada, which, according to the latest annual global survey, is the second most expensive city in North America. Tom was the head of the dentistry library at the University of Toronto, a position that paid $67,000 a year. Salma, with her doctorate in statistics, was earning $117,835 at MetLife as the resident expert on the theories of large numbers. They lived in the Annex neighbourhood, in a four-bedroom, two-bathroom Edwardian with original detailing, a house they had bought in 2003 for $748,499, a full $73,499 above asking. Because they could only manage a $50,000 down payment, they were still paying the government-mandated mortgage insurance, along with the mortgage, which they had acquired from an Australian bank at 5.6 percent. Tom had $7,000 left on his student loans, which he was paying off at the rate of $550 a month. Salma owed over $32,000. The debt burden, though they never admitted it, explained why they had put off having children. They had bought their 2004 Hyundai Elantra through LeaseBusters, a service that transferred broken leases at a discount, which helped.

Salma paid the mortgage, and Tom paid all of the other bills. Either might pick up a dinner cheque or an airline ticket, and they never discussed their finances, because their economy was mutual, instinctive, and inherited. They obeyed the classic Canadian frugalities. Stacks of used yogourt containers, rather than Tupperware, filled the kitchens of their mothers. In restaurants, their families never ordered dishes they could cook at home. Salma considered it a treat to buy a small Cobb salad for lunch at the neighbourhood deli, even though the expense amounted to 1/23,468th of her annual income.

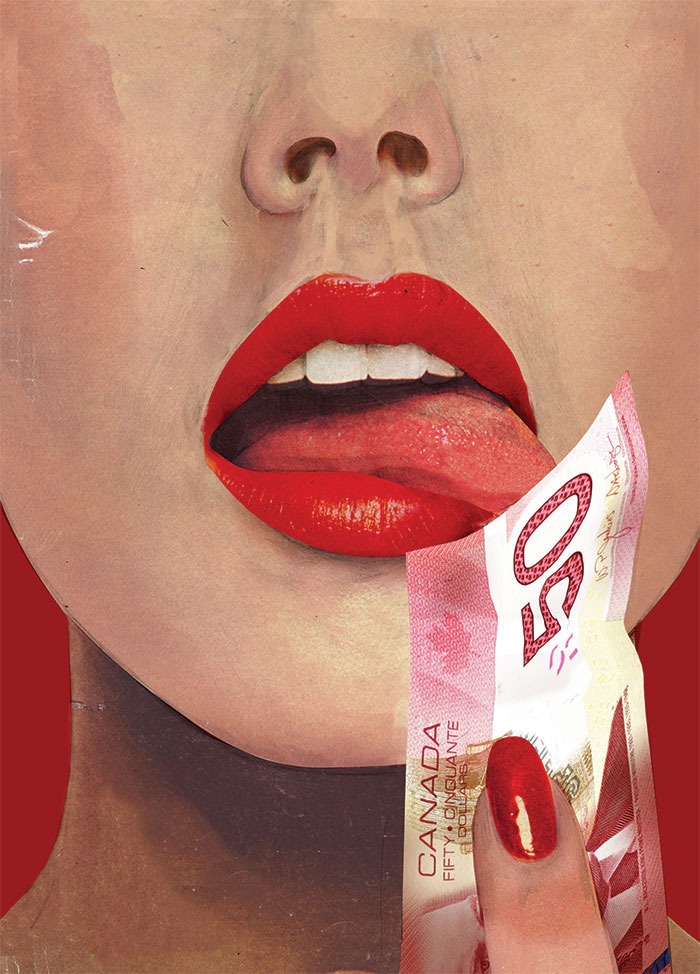

A week after the Health Informatics conference, Tom requested a blow job. He never asked. He always waited for the gift. But Salma couldn’t think of a reason to refuse, and she found his flat insistence, his selfishness, erotic in its freshness. Afterwards, Tom slid a red $50 bill onto the dresser.

“What’s that for?” Salma asked.

“For the cleaning lady,” Tom replied.

“But I pay for the cleaning lady,” she added. Every Tuesday morning, Salma laid out $100 on the kitchen table and tucked a key under the outside mat. She always paid for the cleaning lady, either because she was old fashioned or new fashioned, which is to say either because she needed to seem responsible for the polished floors and the dusted cabinets that Martina polished and dusted every second week, or because she earned more money than Tom did. That afternoon, she was skimming through the new releases on the iTunes Store and somehow spent $62.32—basically every side project Stephin Merritt had ever been involved with—even though her self-imposed limit on iTunes was $50. But maybe $12.32 wasn’t too much to pay for a taste of the illicit. Poor people spent that much on lottery tickets every time they bought gas, Salma imagined. The next morning, she blew Tom again, for the other red fifty still left in his wallet. This time, without pretext, he paid.

They immediately recoiled from their bargain. Saturday afternoon, before a work picnic with the MetLife crowd, quick, aggressively penetrative, effectively refreshing, mutually orgasmic sex proved otherwise. No money changed hands.

And then on Sunday, Marko, their oldest friend from Winnipeg, arrived for one of his impromptu drop-ins, which always drained the eros from their lives as if from well-cleared eavestroughs. When Tom and Salma met, at a model UN at the University of Manitoba, their first mutual desire, before lust or love, was their shared need to leave Winnipeg. Marko had stayed behind in so many ways.

He never shaved, and he wore flannel shirts with the tattooed word “strive” peeking out on his skinny wrist—his whole body seemed to be a big, sinewy wrist—and he belonged to an indie band named Seven Persons that occasionally appeared on the cover of alternative weeklies and filled medium-sized bars and festival venues and wrote mournful songs on unlikely themes like Gordie Howe and the growing importance of lentils to the prairie economy. (That was Salma’s favourite, “Puls.”) The band divided their gig money equitably, the euphonium player making as little as the lead singer, so Marko never brought wine to dinner when he visited from Winnipeg. Instead he told shocking stories of band life, laconically, in a low, steady voice all through dinner: a threesome with two underage Latinas in Brooklyn, a groupie in Japan with a fetish for pickled foods, a bandmate’s decision to only sleep with hookers. Filthy stories were losing their value with age and exposure, and Marko would soon need other reasons to justify not bringing wine.

“So… why no kids yet? ” he asked at the end of the meal.

“You should talk,” Tom said. “The longest relationship you ever had in your life was six weeks with a Newfoundland stripper.”

“Yeah, but I still want kids.”

“You want to practise making kids with your globalized sperm, maybe.”

“I’m just saying. I don’t want what you’ve got, but if I did have what you got, I’d get kids.”

“What would you do with them?” Tom asked.

“I’d walk around and buy them things,” Marko said. “Clothes and books and toys and music.”

“We can’t afford kids yet,” Salma said. A brief pause, everybody sipped wine, and Marko changed the subject to the bicycle lane system back home in the Peg. Not having money is the most shocking story.

That night, after their guest left for an MGMT show, Salma put on the red boots again. Tom was waiting in the bedroom. On the dresser, he had laid out $200 in red fifties.

Tom always paid in red fifties. He had discovered a bank machine near the library that only dispensed fifties, and he started using that machine exclusively. Why was he paying so much? Salma wondered. Was she really worth $50 a throw? Or was it their redness? Was their colour necessary to the shifting nexus of their married desire? The boots were red, she remembered. After a month of exchange, a fifty-dollar bill didn’t seem like money at all, more like a ticket that allowed Tom and Salma to bypass the usual negotiations, the half-serious back rubs and suggestions of showers, and the other hints and feints that used to guide them between their lives as contractually bound, joint-property-owning partners and their lives as lovers.

Lying in the economy of their bed on a hot September morning when they would have been at a cottage if their parents had had money, Tom asked, “Can you calculate the percentage increase in the amount of sex we’ve been having since Orange County?”

“That would depend if you add oral to the total.”

Tom smiled. “I’m a gentleman. I have to include oral.”

Salma tallied the previous week in her head, five red fifties in her billfold. “Three hundred. Maybe 400 percent.”

Tom sighed dreamily. “I think we’ve solved marriage, Sal.”

Tom’s happiness was expensive. Salma learned, profitably, the stranger corners of her husband’s libido. He liked his balls licked. He paid her extra to wear a hockey sweater with Sidney Crosby’s number eighty-seven. She bought a vintage brown billfold for her new money. And she bought music. She bought six lovely Czechoslovakian crystal goblets and a SodaStream and a $200 bottle of balsamic vinegar. For a colleague’s baby shower, she bought a blue and white china bowl from Ashley’s that cost three or four times the appropriate sum for such a present. Carol didn’t send a thank-you card either, which Salma couldn’t understand, until she gave one of her red fifties to the urine-streaked, grey-bearded, furious-eyed homeless man who stood every morning outside Bathurst subway station fidgeting a schizophrenic dance with a baseball cap at his feet, repeating, “Anything is better than nothing, anything is better than nothing, anything is better than nothing,” like a lama priest. She hurried by so the man wouldn’t recognize her, so she wouldn’t be asked for money every morning, but even in that brief moment the dangerous magic of her gift flashed up. The grandeur of his surprised pleasure amounted to an amazed horror. The next morning he wasn’t there. She never saw him again. Had she given him enough money to drink himself to death? To leave town? To return to whatever family he might have? Had she scared him with her red fifty? Or had the man figured he had used up all of the luck and generosity available at Bathurst station?

Despite her spree, the sharp red fifties accumulated in Salma’s vintage brown billfold, as bright and delicate as secrets in marriage. When Carol showed up at the office with her new baby, the baby that had cost Salma $223 at Ashley’s, she cooed and held the precious little body and congratulated Carol just like she was supposed to. Then she snuck to a stall in the bathroom with her wallet, slipped out the red fifties and counted them, and then counted them again. A child is a million-dollar commitment to a perfect stranger.

Salma never asked Tom where the money was coming from, maybe because she didn’t want to embarrass him and maybe because she didn’t want the money to stop. What greater triumph could there be than to bankrupt her husband sexually? They were married, their finances collective, his payments in a sense fictitious. Then again, he was paying for sex they would have already been having. They were both ripping each other off, the definition of a perfect deal.

One night, after Tom had paid for a rather complex set piece involving two fingers of her left hand tucked inside her lips, Salma found him asleep before she had even cleaned herself up. She woke him up by half-jumping on his chest.

“What’s wrong?” he asked.

“Do you love my body?” she asked.

“I don’t think any man could prove it more directly or more often. I mean, I’m nearly broke.”

“Yes, but do you love my body or do you love paying me for my body?”

Tom considered his answer for long enough that Salma wondered if he had fallen asleep again, and began to drift off herself, her thoughts turning, as always in the moments before sleep, to the repairs their Annex Edwardian needed. A thousand for the glass work on the inner back door. Twelve hundred for the bit of rot on the front banister. Their furnace might last another two years.

“Tell you what,” Tom said just when Salma had given up hope of a response. “You can pay me back the money if you want.”

“I love you,” said Salma dismissively.

Whenever she caught a glimpse of a red fifty on the street, handed between a passenger and a cab driver, dispensed into eager hands out of an ATM, accepted with exasperation at a newsstand, a tiny shiver trickled down the small of her back. Toronto is the most reticent and unostentatious of cities, but it vibrated in these moments into a city of hidden arrangements, of manifold unexpressed longings and fulfillments, a city full of sex and money. She loved Toronto, with its solvent banks and its all-nude dancing. Even riding the streetcar through the bland, cheerful downtown on the way home altered into a journey through who knew what dark places. All of that self-proclaimed mediocrity—what was it covering?

Then Tom’s mother, Helen, called one morning to discuss an upcoming visit. Should she rent a car, and should she bring her new lover, Ron, who had lost Tom and Salma’s respect when he described himself, at their first meeting, as “an habitué of used bookstores”? Helen was a radio producer for CBC in Winnipeg, earning $72,373 a year, with excellent benefits and summers off. Salma could almost see Helen as they spoke, her elbows propped on the round kitchen table that she must have paid $60 for thirty years ago at the Brick, in a house right on the ravine, bought for a $5,000 down payment and a $35,000 mortgage, at 12 percent interest, which, paid off a decade ago, must be worth at least $400,000 now.

“You sound different,” Helen said after they had spoken of Ron and rental cars.

“Do I?” Salma was thinking about the homeless man and his disappearance from Bathurst station. Anything is better than nothing. “I’m just busy. We’re both busy.”

“That’s probably true, but before you put Tom on the phone, let me tell you. I’ve heard that sound before in my own voice. Don’t let them push you around.”

“Who?”

“Men. Tom. Don’t let him push you around.”

“Helen, it’s Tom. He’s not pushing me around.”

“All right then, but don’t let him either. It’s nothing against my son. It’s just the way men are.”

Cute, Salma thought after she rang off. What could be more old fashioned than worries about the distribution of power in marriage? Sex and money had long since swallowed all of that nonsense. Helen’s feminism was still charming, Salma thought, but like Victorian jewellery. You could tell it was beautiful, but you’d never wear it.

When the iPad came out, with its too-perfect price of $499, the Gustavsons discussed the matter like sensible business people, and decided that Salma would let Tom sodomize her for the money during a trip they had already planned to Montreal.

Built up over the course of months, the Gustavson libidinal economy crashed with catastrophic swiftness on a Thursday. No one could have seen it coming. Salma was bringing in the Portuguese rotisserie chicken they always ate on Thursday nights, and found Tom at the kitchen table, silent, sucking on a Flying Monkeys Smashbomb Atomic IPA. He hadn’t removed his suit jacket yet. “What’s wrong?” she asked. Maybe Helen had died.

“I hit a kid,” Tom said. “I killed somebody.”

She put the bag of chicken on the floor. “How?”

“On Crawford Street. I was turning right, changing from the third track to the fourth on the new Dirty Projectors.”

“From the one you hate.”

“The one I hate, and he was running out after a bright orange hockey ball.”

“Honey.”

“No more than a tap. One one-hundredth of a metre per second per second less.”

“Did you talk to the police?”

“They talked to me. They’re the only people I’ve talked to. His friends all vanished. Before the crowd gathered, the street was so empty. He was so still and peaceful and white.”

“Come here.”

“In his Maple Leafs gear.”

Salma leaned over to embrace her husband, but he recoiled into the bedroom instead, to curl up on the edge of their mattress. Half an hour later, Salma looked in, almost asked him if he wanted any chicken. She could tell, even then, that he didn’t want to be touched.

The business of the accident was almost too simple. Two witnesses had seen the boy dart out from between the cars. The police informed Tom, during a follow-up interview, that there was nothing he could have done. His lawyer’s fees amounted to $7,619.67, which seemed expensive to Tom since he never came near a courtroom. At least his insurance didn’t go up. The company declared him zero percent at fault. He had to buy a new car, a 2006 Echo, but they needed a new car anyway. All in all, the financial consequences of the little boy’s death were minimal.

Tom walked around the house in a stupor, watching hockey or listening to long pieces of music, classical music, Sibelius symphonies he hadn’t heard since college. One Saturday afternoon, Salma found him lying naked in bed, listening to a late Beethoven string quartet with his eyes closed. She took off her own clothes and lay beside him. He roused a little but didn’t open his eyes. Salma whispered in his ear, “You know there’s no way you could have missed that little boy, right?”

He shifted closer. “It’s not that.”

“Then what is it?” she asked.

He considered the question with perfect stillness. “It’s the possibility of catastrophe everywhere, all the time.”

Salma licked his face. “I can’t,” Tom said.

“Please,” she mumbled.

“I just cannot.”

And he couldn’t.

Later that week, Tom brought home a cat, a small tabby he called Delius, Deedee for short. A long, lithe creature with supercilious eyes. Salma was upset that Tom hadn’t discussed the matter with her, but he insisted he was going to pay for all of the cat’s expenses and take care of all the chores surrounding its domestic business. Salma didn’t argue too insistently, because she could see how the cat relaxed him. Delius’s presence was as calming as music to Tom.

Salma’s collection of red fifties was vanishing, and with them her patience. She had forgotten about using a bank card. The procedure was so drearily bureaucratic, inserting plastic into a slot for jurisdictionally correct credits. She spent the last of Tom’s fifties on a Halloumi sandwich and a cappuccino at an Israeli café in their neighbourhood, and the change—the green twenty, the purple ten, the blue five—grubbied her palm like the thought of divorce. She snapped at the girl who delivered her cappuccino because she had asked for extra foam but the coffee was all foam and she hadn’t asked for a macchiato. The girl, dark, slim, just barely post-collegiate, with a leather necklace and feather earrings—how much did she make, $10, $12 an hour?—dumped the rejected brew and started over without a word.

That night, Tom came home to find Salma naked on the chair in front of the mirror, drinking red wine. He went down to the basement and put on headphones. When she called him back upstairs, he returned to find his wife with her legs spread on the kitchen table, engulfing a long red sausage with compelling vigour. All he could do was watch apologetically until she orgasmed.

“No?” she asked.

“Nothing,” he replied.

“Really nothing?”

“A big zero.”

They fried the sausage mournfully, compassionate with each other.

Marko returned with his band in the spring, and the three sat around on the floor, eating takeout Middle Eastern as if nothing had happened, except that Delius now stalked the fried eggplant and the pickled beets. “So you got a cat instead of a kid?” Marko asked.

“Her name is Delius,” Tom said.

“I told you to have kids and you wind up with a cat. Doesn’t seem like a fair trade.”

“You’re like an old Winnipeg grandmother,” Salma said. “Always harping on the womb.”

“I love this cat and I don’t want to hear either of you insult her,” Tom said flatly.

Marko intuited a story weird enough that it might develop into a song. An adulterous affair between a man and a cat, or something like that. “Why do you love Delius, Tom?” Marko asked.

Tom scooped hummus into a warm pita. “She doesn’t stop,” he said.

Now Marko knew he had a song. “Explain.”

“She’s so lugubrious, so instantaneous with her movements. So fluid.”

Marko considered. “The opposite of machinery.”

“Exactly.”

Marko stared semi-ecstatically at the ceiling, trying to fit it all into a pattern that might rhyme and follow chords. Desire for Marko flushed through Salma, not just to taste his body but to sell everything for his body, to follow him into his financial hand-to-mouthness, to leave insurance forever and follow an indie band where events were interesting because of the songs they might provide. It was like that ballad “Black Jack Davy” the Carter Family used to sing:

Come go with me, my pretty little miss

Come go with me, my honey.

I’ll take you across the deep blue sea

Where you never shall want for money.

Marko should write a song like that.

The Gustavsons’ marriage survived the crash. Their redemption arrived in the fall when Delius found the boots. The crystal studs against the red leather proved too perfect a cat’s plaything. When Salma discovered them, ruined, she mechanically launched Delius across the room with her foot. Tom ran to the yowling and found Salma cradling the scarred boots, tears streaming down her face like a high school girl in some dumb pop tune.

“What’s the matter? What’s the matter?” Tom pleaded.

“I loved those boots. They were so expensive.”

“Let me buy you another pair. I can buy you another pair. We can afford it.”

“I don’t want compensation. That’s the opposite of what I want. I don’t want to be tallying everything up little by little, and being prudent and buying and selling and insurance and everything in quantities.”

“What do you want, then?”

Salma thought about all of the money he had spent on her. Those were the happy days, the days of foolish presents, the days of gift and theft. “I want a baby,” she said at last, resigned to the cost of living.

And that is how Emmy, little Emmanuelle Singer Gustavson, came into the world of flesh and numbers.

This appeared in the December 2012 issue.