At 40 metres long and 540 tonnes, the Chameau was a powerful frigate, designed to carry people and goods to New France and take natural resources back to Europe. She was a fast ship but a cranky one; when the weather got bad, she would toss like a toy boat in a bathtub. On her final voyage, the Chameau was carrying approximately 100,000 livres in gold, silver, and copper—along with 316 passengers, including the newly appointed intendant of New France. As she approached the coast of Nova Scotia in August 1725, a southeast wind rocked the waters. By nightfall, a squall had brewed, thrashing the vessel. It plunged into a reef, where it broke apart and sank into the depths. There were no survivors. Most perished in the storm; those who didn’t were either consumed by the undertow, or died from exhaustion after washing ashore near the fort town of Louisbourg.

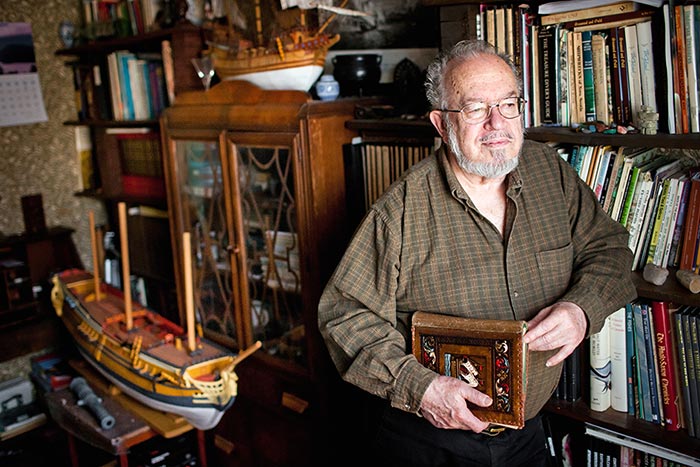

In 1961, twenty-three-year-old Louisbourg transplant Alex Storm was thumbing through a history of his adopted home, by then a fishing community. His interest was piqued by the story of the Chameau. A recent émigré from Indonesia, where his family had been imprisoned in Japanese-run internment camps during World War II, he had settled in Nova Scotia and volunteered for a position aboard the Marion Kent. Taking advantage of the circumstances, he dove near Chameau Rock, the ostensible site of the wreck, and came upon a cluster of some twenty cannons, strewn alongside anchors and guns. “It was a solemn moment, because I knew that no one had seen it since the night when the ship wrecked,” he recalls from his home nearby. But the expedition yielded more than history: glinting among the ruins was a single silver four-livre piece, embossed with the year 1724 and a portrait of King Louis XV.

Parks and Wreck

Digging online and in public for buried treasure

Peter Ryan

Tech-savvy treasure hunters need not rely on crumbling maps where X marks the spot; instead, they can go geocaching. In this “high-tech treasure hunting game,” created in 2000, would-be adventurers seek out buried treasures, or caches, by obtaining coordinates from geocaching.com and entering them into dedicated GPS devices. Once they find their bounty—generally a small plastic container holding a logbook, and trinkets they can keep in exchange for their own contributions—they add it to their online profiles. The game’s website advertises over a million active caches, across all seven continents. Though it sounds like little more than nerdy fun, geocaching has its detractors. Many American parks have banned it, out of concern that players harm the environment by planting containers and increasing traffic to cache sites. Some park staff just find it strange. “The underlying problem,” Marcia Keener, a U.S. National Park Service program analyst, told a reporter, “is that we are not historically comfortable dealing with anonymous people doing activities in the parks.”

—Amelia Schonbek

The coin was a small discovery, but one that set Storm on a mission to find the rest of the Chameau’s loot. He took a job with an underwater archaeologist and, in his spare time, familiarized himself with eighteenth-century ships, and gathered weather reports and ocean current data from the night the Chameau went down. He assembled a team of divers, and in 1965 located the ship’s final resting place. There, along the gully and the cracks in the bedrock, Storm found his treasure: over 2,000 gold louis d’or coins and more than 11,000 silver livres, which later sold for untold millions at auction.

His discovery was a watershed moment in the province, the first time a treasure wreck was discovered by a recreational diver. “Alex Storm is the grandfather of it all,” says Terry Dwyer, a shipwreck expert and explorer. “He probably initiated the industry of searching for shipwrecks for treasure hunting and for salvage.” Dwyer, a thirty-year veteran, has uncovered his own share of historical ruins: in the summer of 2000, he located the Anna, a full-rigged British ship that had sunk off St. Paul Island, Nova Scotia, in 1874. In 2009, his team found parts of the Sovereign, another British ship that sank near the end of the War of 1812.

Nova Scotia holds special prestige for marine treasure hunters. Navies, cargo ships, privateers, and fishermen have sailed its waters for hundreds of years. Its traffic, as well as its rugged, stark coastlines, have left an astonishing number of shipwrecks dotting the ocean floor. A study released by the provincial government estimates that its coastal waters might hold upwards of 10,000 shipwrecks, compared with 50,000 in the entire United States.

But the provincial government has put an end to the industry Storm set in motion. Since 1954, the interests of private hunters have been secured by the Treasure Trove Act, a unique piece of legislation that permitted the salvaging of treasure (defined as “precious stones or metals in a state other than their natural state”) from shipwrecks. At the beginning of this year, the province repealed the act, following a recommendation from a provincial task force, which cited the need to protect Nova Scotia’s underwater cultural heritage.

The repeal may ensure that Nova Scotia’s heritage stays in the province, but it raises an entirely new problem: without private sector salvagers, no one would find anything. The province lacks the resources to even locate (much less recover) shipwrecks, and the treasure hunting report suggests that a handful of profit-motivated parties—divers and private companies—are responsible for the bulk of underwater discoveries so far; both Storm and Dwyer estimate that number to be close to 99 percent.

Clearly, heritage alone is not enough to motivate the recovery of underwater artifacts; it is the promise of gold that sets salvagers’ hearts racing. For Storm, that silver piece was only the beginning. After auctioning off his gold coins from the Chameau for between $3,000 and $8,000 apiece, he continued to chase riches. In 1968, he located the remains of hms Feversham, a seventeenth-century British warship, part of a fleet sent to attack Quebec. Although glittering prizes were always his ultimate goal, the lure of adventure—like that of the stout-hearted sailors in his history books—gave him momentum. “Just like a mountain climber, you need to climb the mountain because it’s there,” Storm says, in his lilting East Coast brogue. Now in his seventies, he is distinguished by a coarse white beard and skin tanned from years of seafaring.

This appeared in the May 2011 issue.