Fernand Meyssonnier’s fingers are clutching the back of my ears, pulling my head out as if it were a steering wheel being salvaged from a smashed car. His thumbs dig in and I’m being literally raised up off a chair in his office.

“It’s like this,” he says, pulling harder.

He’s showing me how he used to hold a prisoner’s head at the guillotine. He’s doing a good job of it and I fumble some words, hoping he’ll call off the demonstration.

For fourteen years, Meyssonnier operated a guillotine in Algeria while the country was a French colony. Working alongside his father, he executed two hundred people, all but two of them Algerian. Few people better personify—or are more proud of—the civilizing mission undertaken by France around the world than Meyssonnier.

“When France was in Algeria, there was justice,” he says, sitting back in his chair. “More or less. But now that France is no longer there, the Arabs, they’re worse than the French. It was “the suitcase or the coffin.’ The French packed their suitcases and left and now the Arabs are killing each other.”

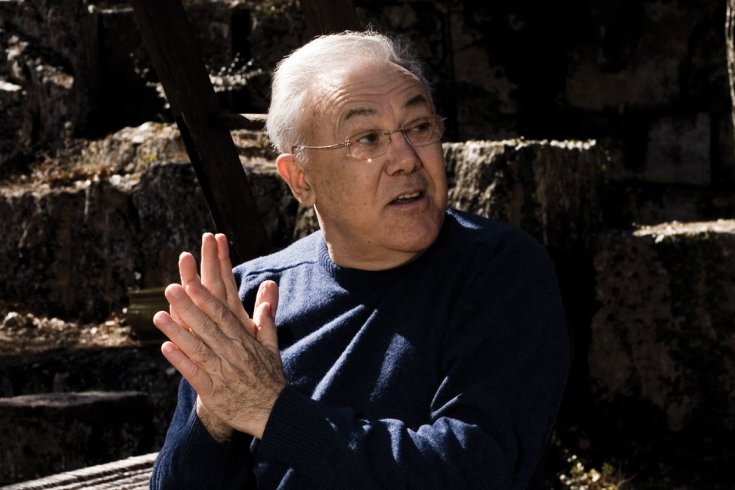

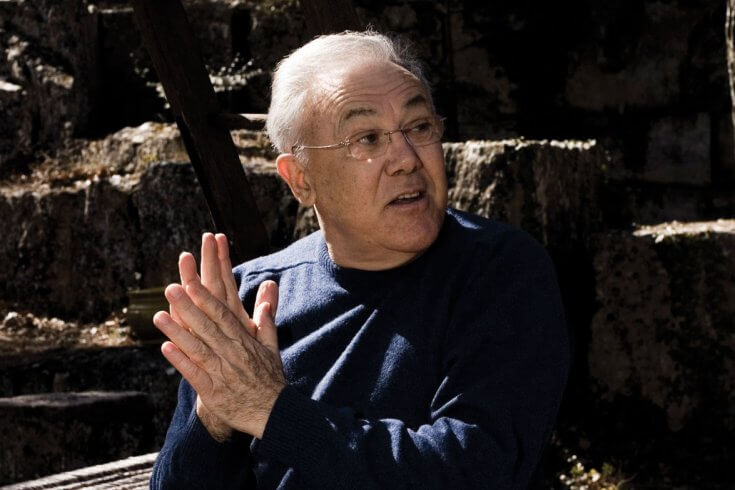

Some people would characterize Meyssonnier as a right-wing Frenchman concerned about foreigners and immigration, issues that have recently dominated the news. But he also looks like any other seventy-four-year-old you might see sitting on a park bench feeding pigeons. He is broad chested, with a large head that age has given the appearance of softly shaped marzipan. His hands are bulky and the gold chain beneath his buttoned-down shirt dangles above his grey chest hairs.

Meyssonnier has been living with his Tahitian common-law wife, Simone, in southern France since the early 1990s. They live in Fontaine-de-Vaucluse, a small town near Avignon that is famous for its resurgent springs and the towering brick archways of the nineteenth-century Aqueduc de Galas.

Meyssonnier says everyone in town knows his past as an executioner, and that any poor relations are due more to jealousy over his successful real estate investments. But there is a third possibility: “I’m pure French, but born in Algeria,” he says. “There you go.”

Were it only that simple. France claims it does not recognize hyphenated identities, the two-for-one-special some Canadians rely on to describe themselves. Nevertheless, it’s a phantasm that permeates France, one that is used to discriminate against those who are not white or not born here.

In fact, even Meyssonnier, who is a French citizen, is known to many here as a pied-noir (black foot)—a European colonial immigrant in North Africa. Most pieds-noirs were French and left Algeria in the 1960s. For the most part, they have been assimilated into French society and no longer experience the discrimination suffered by the country’s African immigrants. Nevertheless, in some ways, they remain apart from their French brethren as symbols of the dirty era of colonialism.

When I first arrived at Meyssonnier’s home, he introduced me to Tama and Michel, two green parrots that can sing the Marseillaise. A model reproduction of a guillotine, built by Meyssonnier when he was fourteen, stood enclosed in a glass case in the living room.

For much of my visit, Meyssonnier’s wife remained invisible, a disembodied voice shouting down from an upstairs bedroom. She’s been living common-law with Meyssonnier since the two met forty-three years ago in Tahiti. Their forty-two-year-old daughter Taina still lives there, where she works for the tourism board.

Meyssonnier is disappointed that his daughter hasn’t shown much interest in his former career. It was different in Algeria, he says. There, the work of an executioner was appreciated and respected by both the French and Algerians alike.

“In France, being an executioner is like being a printer or a hair stylist,” he says. “Whereas in Algeria, an executioner had power. People didn’t do it to earn a living. My father would have continued doing the job for free if they’d stopped paying him.”

When Meyssonnier’s father wasn’t executing people, he was running a bar in the capital, Algiers. Because the work of an executioner is often passed down from one generation to the next, it was Maurice Meyssonnier who invited his son to join him at the guillotine.

Leading me to an office on the second floor of his house, Meyssonnier begins sifting through records that he keeps in brown cardboard boxes. The papers have faded to the colour of the naked Hawaiian women posing in pictures on the wall, but the patriotic tri-colour embossments still stand out.

Meyssonnier picks up one binder and turns to five pages of hypnotically fluid script. It’s his father’s execution log from 1956 to 1959.

Zahane Amed Algiers 19 June 1956

Ferradj Abdelkader Algiers 19 June 1956

Belkhairia Mahmed Constantine 7 August 1956

“They admitted their crimes,” he says, flipping through the pages. “Even as they were taken to the guillotine, they were bragging about what they had done. You give a bomb to a terrorist, it’s not to celebrate July Fourth, eh”

He says a few of the convicts, however, were simple criminals taking advantage of the chaos in Algeria to break the law. He could always tell them apart from the mujahedeen at the guillotine. “Some collapsed or pissed themselves or threw themselves on the ground. But the ones who believed in the ideal of Algerian independence, the guys who died saying, “Long live a free Algeria,’ showed an extreme courage that even the French didn’t have.”

Meyssonnier was sixteen when he saw his first execution, in 1947. He nearly didn’t go because he was afraid it would be too gruesome. He ended up standing within two metres of the guillotine. People were whispering. He heard the call to prayer and roosters crowing. Then the prisoner was mounted on the guillotine.

“Was there blood” says Meyssonnier, surprised at the obvious question I ask him. “But of course! Yes, yes. Five, seven litres empties out. It’s not the electric chair, eh Jets of blood spray out three metres. Like two glasses being emptied.” His hands jettison two imaginary drinks.

“The smell of human blood is unique,” he continues. “Just like the horse butcher doesn’t smell like the regular butcher. Human blood, you have to wash it off, it smells. We washed the guillotine, but not with soap.”

In slow motion, he mimics holding a heavy hose, like a scene out of a fireman’s pin-up calendar.

“Pwwssshhhhh! That’s what we do. With a jet of water, it’s clean. But the smell—it’s an odd, characteristic smell.”

Meyssonnier’s main job during the execution was keeping a condemned man from retracting his head on the guillotine. Not even the lunette, the wooden brace that secured a person’s head in place, was enough to stop some individuals from trying to withdraw their heads (like turtles retreat into their shells.) If that happened, the blade could miss cutting along the jaw line and leave the head partially attached—requiring either another go with the guillotine or cutting the head off with a knife—a gory ending that no one liked.

Hence, Meyssonnier would hold a convict’s head tight behind the ears. Vas-y, he’d tell his father, and without another word, Maurice Meyssonnier would pull the lever that released the blade.

“The blade weighed forty kilograms, but travelling down 2.35 metres of space, it becomes 700 kilograms,” he says. “That cuts, eh.”

It was dangerous work, least of all because the convicts sometimes tried to bite. It’s amazing that neither Meyssonnier was assassinated during “les événements,” the French term given to the Algerian War of Independence, which bled on for eight years and claimed at least 300,000 lives. Meyssonnier left Algeria by boat in 1961, a little over a year before the country declared independence. He was thirty years old. His father, who was fifty-nine, made the mistake of staying, and was caught and tortured.

“It was madness,” says Meyssonnier. “Everyone leaving and he, the executioner, decides to stay. They strangled him, punched him in the ribs, everything.” Meyssonier’s father died of throat cancer two years later, back in France.

More than 900,000 pieds-noirs fled the country in 1962, most of them moving to France. Roughly 91,000 harkis, Muslim Algerians who fought alongside the colonists or helped their cause followed. Today, the Arabs who left for economic and political salvation live mainly in high-rises in the banlieues, teetering on France’s economic and social fringe.

“Immigration in France—the Arabs, the blacks—it’s terrible,” says Meyssonnier. “You go to the thirteenth arrondissement in Paris, where the Chinese are, there’s no problem. The Spaniards No problem. The Portuguese Nope. Italians None there either. The only problems are with the blacks and the Arabs.”

After spending some time with Meyssonnier, it’s easy to see Europe’s boiling immigration problems as a potential calamity—a subject he is passionate about. “We have to help the blacks of Africa in their homelands,” he says. “Give them systems to pump water, not powdered milk.”

When I ask Meyssonnier why he hasn’t left France, considering his unhappiness with the direction it is taking, he sighs and shrugs: “And go where” He has never returned to Algeria. He has never seen pictures of his old house there. In fact, he has avoided all photographs of modern-day Algeria entirely.

Instead, his vision of France beckons. It would be a society that championed the death penalty, that eschewed harsh life sentences, and that likely had far fewer communists and immigrants. It would forbid police brutality—the kind he has seen in U.S. television footage.

“Here, it’s the opposite. They burn cars and we say: ‘Why did you burn the car, oh-oh-oh.’” Meyssonnier coos softly, shaking his head.

His words turned out to be prophetic. A few days after my visit, France exploded in ethnic rioting. The spark came in the deaths of two young men, accidentally electrocuted while hiding from the police. Over a three-week period, youths, primarily of North African and African descent, burned nearly 9,000 vehicles, damaged 200 buildings, and killed a senior citizen. It was unlike anything seen in France in decades. A state of emergency was declared and 2,888 people were arrested.

A few weeks later, France’s National Assembly voted to uphold a law decreeing that schools must call attention to the positive role France played as a colonial power. Despite thousands of additional police sent to patrol suburban housing projects this past New Year’s Eve, people still torched 425 vehicles, more than the previous year.

Teeming ghettos; angry, unemployed youths; burnt cars. It has been reduced to a simple equation and glaring headlines, but the reality is more complicated. The socio-political landscape is deeply and subtly stratified, and the country is governed by an economy that coddles the employed and locks out most others, particularly the country’s North and West African immigrants. They remain separate, trapped by history. Like Meyssonnier.

Back in Fontaine-de-Vaucluse, a faded, poster-sized photograph hangs above a night table in Meyssonnier’s guest room. It’s a picture of Meyssonnier and his wife, taken in the early 1980s at Roissy Airport in Paris. Fernand and Simone look elegant yet out of place, dressed in knee-length fur coats, standing in front of the airport’s space-age terminals. The photograph seems to sum up France so well—here was a Frenchman who had lived in France for decades, but who, in some people’s eyes, may as well have arrived yesterday.

Later on, when I finally meet Simone, I ask her what she thinks about her husband’s work as an executioner.

“It’s too bad, because it’s interesting,” she says while feeding almonds to the parrots. “Sometimes I listen to him, but I’m not into it. My daughter likes it even less. When the book [an autobiography titled Paroles de Bourreau that was published in 2002] came out, her girlfriends said, ‘Hey, this Meyssonnier, is he related to you? ’”

Later that morning in his office, Meyssonnier shows me a catalogue listing a series of torture and punishment artifacts he has been collecting for over thirty years. Selling the collection and leaving the money to his daughter has become his main preoccupation. He values the entire collection at $800,000, including the guillotine from Algeria (item 305, $450,236.51) and a preserved nineteenth-century assassin’s head (item 218, $6,282.37).

What worries him greatly is the possibility that he may die before selling the pieces. Two years ago, he was diagnosed with stomach and liver cancer. He has been in remission since having 400 grams of his liver removed, but he credits his longevity to a $3,830 monthly medication program.

Meyssonnier says he has approached the French government about his guillotine, but it has yet to express interest in it or the rest of his collection.

“They’re hypocrites,” he says. “In France, there’s this belief that we never relied on torture. That it was the Germans, the Italians, the Spanish. But there has been horrifying torture. I’ve seen history.”

Seen it, but never lost sleep over it. Meyssonnier says he has never had a dream, let alone a nightmare, about his executions.

“That said, if I’d executed a criminal knowing he was innocent, well, then” He inhales deeply before continuing to answer a question he has surely been asked before.

“I would have been unhappy. And that doesn’t mean it’s me. I was given an order. But to have participated in a crime—because killing someone who is innocent the guys we did were still bragging about their crimes. So there’s really no doubt possible.”

I wait for more, for some sign of reservation or the doubt he has dismissed. But Meyssonnier’s silence fills the room. He looks weary, aged.

Back in the living room, a large bronze bust sits atop shelves of wine glasses. The head is Meyssonnier’s, and it seems especially lifelike because someone has placed a straw hat and eyeglasses on it.

“I don’t want to be buried,” he says when he sees me examining the bust shortly before leaving. “All that rotting. I prefer to be incinerated, and I’m going to have the ashes put in that.”

Simone, who is lying on the couch across the room, rolls her eyes. Perhaps the thought of Meyssonnier floating around here in the spiritual realm seems weird even to her. I ask Meyssonnier if he’s afraid of death. He laughs.

“If me, I, was afraid of death, well that, that would be idiotic, eh Really. The guy kills 200 people and now he’s afraid of death No. On the other hand, I wouldn’t want to be guillotined, eh. That, I wouldn’t like.”