As I write this, one of my cats is sitting on my lap. If a cat is not on my lap, or playing chase across the keyboard, or meowing for attention; if a cat is not calling for more food or fresh water, or seeking the warmth and tickle of my hand and the sound of my voice saying, “Yes, you are a lovely cat,” it is because all three of them have finally wandered away to warmer corners of the house for their naps. Principessa, my clumsy and rambunctious collie, stays outdoors. If she were inside, she would make it impossible for me to do anything besides entertain her and provide her with constant reassurance that she is loved and noticed. Her favourite trick is to run circles around an unsuspecting human, and once her target is sufficiently overwhelmed, to flop on her back for a tummy scratch. There is no such thing in her world as too much attention.

As a veterinarian with a practice in rural Quebec, I live and work with animals, but I still find it hard to let go of a sense of wonder when I consider our relationship to cats and dogs. I continue to be amazed at the way these two particular species have become fixtures on the positive side of our emotional experience—at the same time that livestock and poultry are increasingly invisible, distant from our thoughts and our daily lives. The gap between pets as companions and the flocks and herds of similarly sentient creatures that provide us with food seems to be widening each year. The deeper our empathy grows toward pets, the more startling becomes our indifference to the animals we eat.

After a few thousand years of providing casual companionship and help with hunting, guarding, and pest control, it has taken only fifty years, along with a few technological and medical innovations, to allow cats and dogs to cross the final frontiers that separated them from the most intimate spaces in our homes. Now they sleep in our children’s arms, occupy our beds, stroll along our countertops, and laze in our bathroom sinks.

It was only in 1947 that cats moved indoors full time. This was when clay-based kitty litter was first commercialized, a product that was much cleaner than the sand-, dirt-, or ash-filled boxes that people had previously used. When cats crossed the threshold, their needs became integrated with the family’s. Before, if a cat fell sick, we would assume that it was too late to treat whatever was wrong with it. We assumed the animal would know it was time to head off to a secluded place to die. That was “natural.” Now, we consider it natural to go to extremes to address our pets’ illnesses, prolong their lives, and respond to their suffering from the earliest signs. Even though cats are famously grumpy patients—I can attest to that—they do seem to know we are trying to help. At least, we like to think they do.

These changes have all come about since the early twentieth century, when feline medicine was even more marginal than the lowly canine practice. In those days, veterinarians treated large animals exclusively; the most skilful ones specialized in horses. When automobiles began to replace horses, many veterinarians felt that their profession was on the wane. In fact, the boom in animal care was still to come.

Today, there are 9,602 licensed veterinarians in Canada, of which 4,347 work with pets. With so many cat and dog doctors out there, specialized knowledge inevitably trickles down. Experienced cat owners have learned to identify a few common feline diseases; they know, for instance, that a middle-aged cat who suddenly loses a significant amount of weight might be suffering from diabetes, an overactive thyroid, or cancer. For dog owners, the first signs of bladder infection are small red-tinged puddles in the house. Nutrition and health care (including anti-flea medication that is almost 100-percent effective), along with a few grooming techniques, have made life with pets much more manageable.

Cats and dogs now have longer life expectancies than ever, which has forced us to recalibrate the standard equation of one human year equalling seven dog or cat years. A few years ago, I assisted with the euthanasia of a thirty-year-old Siamese cat—the wizened feline equivalent of Jeanne Calment, who died in 1997 at the record age of 122.

Our connection to pets is so strong that we will do anything to keep them alive. We initially become attached to our animals because of their temperament and idiosyncrasies: kittens are predictably cuddly and playful, dogs cheerful and mature, cats enigmatic. Their habits soon become part of our daily routines, and a source of comfort; health researchers have noted that animals reduce tension and anxiety levels in humans. While people might once have considered it silly to grieve over an animal’s death, it is now perfectly acceptable to mourn the death of one’s pet, sometimes to the same degree as the death of a close friend.

Our pets now share our lives in every way, including many of the same diseases and lifestyle risks: a rising obesity rate from too many cheap and easy calories, hormonal disorders, arthritis, cancers, and the indignities of geriatric life. Like us, they also face the potential dilemma of being unwanted. One of the most common causes of death in cats and dogs is euthanasia for unclaimed or abandoned individuals; the Canadian Federation of Humane Societies estimates that 19 percent of dogs and 43 percent of cats presented to shelters are euthanized.

We love them, we leave them. And still, cats and dogs are the animals we care for the most. We have developed safe and mostly painless ways to tidy up the messy problems of their sex drive (and they go on to behave as if they hadn’t lost a vital part of themselves). Best of all, they look us in the eye and inspire a response.

I believe that cats have a specific cat-to-human dialect. Nearly every cat I know appears to talk to humans, using sounds and a register that they don’t use to communicate among themselves. One study I still like to cite, even though it was done in the 1940s, concluded that felines have a vocabulary that includes expressions of acknowledgement (“mhrng”), bewilderment (“ma ou:? ”), and anger (“wa:ou:”). (The colons indicate vowel prolongation.) The cat-word I hear most often around my house is “mhng-a:ou,” a complaint applied to the children, the weather, a lack of attention, and most of the time, each other.

I never fail to notice when writers and celebrities admit their attachment to pets. Doris Lessing and Colette have loved their cats in print. Marley and Me, the story of a relationship with a dog, has occupied bestseller lists for more than a year, and Roy MacGregor has followed up with The Dog and I. Interspecies friendships seem to be on the rise.

The manner in which people make pets part of the family is touching; it sometimes distracts me from my disappointment over the conventional brutality of human conflict, our inability to maintain sensible momentum toward social and economic justice, and our muddle-headedness about environmental distress. It’s been a long road to canine and feline integration, but we now seem to have arrived at a place of mutual good feeling. Humans and their cats and dogs have bonded.

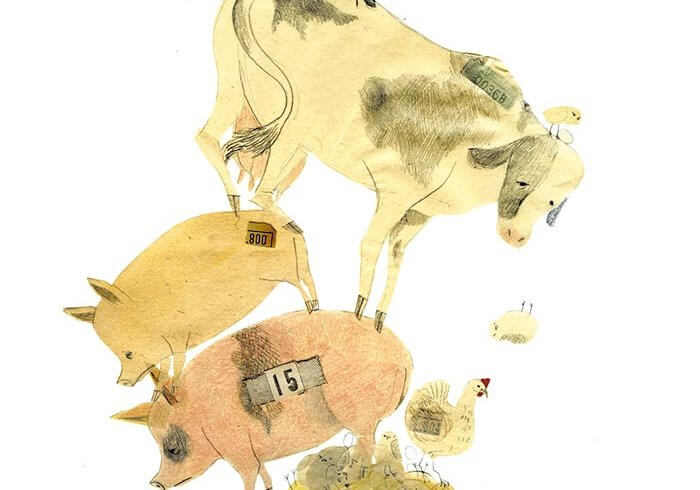

This is the success story of our relationship with animals. Now for the depressing part. When it comes to cows, pigs, chickens, and, more and more in Canada, sheep, it seems as though we would prefer it if these animals were efficient machines or fast-growing plants. In North America, during roughly the same period in which our attachment to dogs and cats has become so intense, we have increasingly segregated these other domesticated animals from everyday life and kept ourselves in the dark about the unpleasant specifics of industrial farming and slaughterhouse conditions.

If only eggs would grow in petri dishes instead of inside hens, locked up in tiny cubicles in windowless warehouses, then this most perfect food wouldn’t be spoiled by our knowledge that something about the process seems terribly wrong. The senses we share with animals tell us it is wrong, but because most of us are physically removed from the realities of industrial farms, these instincts and sensations stay buried, and we are soothed instead by the arguments of advertising and accounting.

On several occasions, I have tried to overcome these instincts through repeated exposure, but this turned out to have the opposite effect. I remain shaken by the scale and structure of industrial farming—by feedlots in Saskatchewan and Alberta that host fifteen thousand head of cattle, by mégaporcheries hidden at the ends of rural roads throughout Quebec (credibly exposed in Hugo Latulippe’s 2001 documentary, Bacon, le film), and especially by our versions of industrial American dairies, which are remarkably inefficient.

On industrial dairy farms, many cows become lame or infertile, or are culled for ground beef at an early age because of the stresses associated with intensive milking. Before a farm can profit from a cow, she must be raised to maturity (which takes fifteen months, during which time she receives vaccinations, other medical care, and specialized feed), successfully impregnated (nine months), and milked through her first lactation cycle (ten months). Not until the second lactation cycle, following another gestation period, does a cow’s milk production pay off the initial investment. Thanks to superior genetics, milk production averages an impressive 9,242 kilograms per cow per year, but individual cows are not valued. Only the sheer scale of the industry and the demand for cheap hamburger seem to prevent the system from collapse.

Cutting-edge poultry and egg operations are even less humane. And when these manufacturers boast of having achieved a source of cheap protein that is safe and nutritious, they fail to mention that the meat and eggs are also tasteless and that the truly affordable wings and thighs contain too much grease, water, and gristle. My kids refuse to eat bland white mass-produced breast meat even when it’s fried in crispy batter and served with honey sauce. They’ve tasted better chicken closer to home, and they’re holding out till it comes around again.

In veterinary school, I learned about chicken anatomy and physiology, and about virulent and contagious diseases—serious threats to chickens kept in overcrowded, stressful conditions. Once, we visited a chicken abattoir, following which my roommate was ill for ten days with a confirmed case of campylobacter diarrhea even though she had not come close to a carcass. We also studied the problems of heart failure and ruptured leg tendons, and observed scientists penetrating the chicken genome in pursuit of new ways to maximize production.

Now that I live on a small farm with chickens, I have seen first-hand how they enjoy foraging for grass and scrounging and pecking for earthworms. But in veterinary schools, there is little or no discussion of the value of foraging. Also barely mentioned are the human-animal bond and gerontology, both of which have become serious issues in dog and cat medicine. No wonder there are only about fifty poultry vets in Canada; students don’t want to be chicken doctors.

Domestic chickens have essentially been split into two separate groups. The skinny “frugal” breeds don’t put much flesh on their bones, and their metabolism is devoted to pushing out an egg every day. But at least they are mobile—or would be if they didn’t spend their short, disposable lives in laying cages. The other group comprises the heavy meat-producing breeds with huge breasts and names like Color-Pac or Cobb 500 Slow-Feathering Females. These are genetically selected to grow from a weight of about 40 grams to 2.5 kilograms in only six weeks. They remind me of garden vegetables that must be harvested before they become overripe, lest they rot. Many of these factory birds develop gait problems, waddling around top-heavy. Slaughter must come as a relief; if it is delayed, some birds develop a water-retaining condition called ascites, which is a symptom of heart failure.

Ihave been raising laying hens on our farm for the past few years. Two of them turned three this year and still manage to produce an egg every day or two. Once their laying days are over, we sometimes turn them into slow food, such as poule bouillie, which involves a few hours of slow boiling in the oven or on the stove, then a short broil for crispier flesh. (It’s also slow because you need a few days to get your mind around the fact that you are going to kill.) That is the kind of chicken my kids will agree to eat. They remember the taste for months afterward.

Unlike my love-starved collie, chickens aren’t demanding or particularly needy, and it wouldn’t occur to them to monopolize my attention. A balanced diet, water, a few nests for the eggs, and a place up high to roost at night is all they require, but they don’t mind if I hang around long enough to say a few nice words. Introducing new birds among them has to be supervised and managed gradually, or else there can be fights. (Commercial operations deal with this problem by slicing off the sharp point of the beak.) This year in Canada, few chickens will be sitting outside in the morning sun, feeling the cool summer rains, or taking dust baths—the Canadian Food Inspection Agency has recommended that all poultry be kept under house arrest because of the threat of avian flu.

I’ve tried to make up for this with extras from the kitchen and garden, and with more hay and straw pour leur faire plaisir (as my son says when he digs up earthworms from the garden to give them). My hens have overcome their fear and general dislike of animals bigger than themselves, and one of them sometimes stands still to let me stroke her just above the tail feathers. It’s the same way I stroke my cats. And like the cats, my hens look me right in the eye when I give them the chance.

In the vast numbers of the industrial food chain, chickens, cows, and pigs don’t get the chance to look us in the eye. This detachment hardens us to the periodic culls that such conditions help create. How easily we dispose of our “food animals,” either for economic reasons or out of our sometimes unreasonable fears of animal-spread disease.

For instance, in 2001, foot-and-mouth disease swooped in and knocked the wind out of agriculture in the United Kingdom, resulting in massive culls that were the result of exposure—or potential exposure—to the virus. The numbers climbed quickly into the hundreds of thousands, and there wasn’t enough space to bury or burn the mounting piles of corpses. Some farmers committed suicide in response to this final assault on a way of life already being crushed by industrialized farming. In the end, more than four million sheep, cattle, and pigs were culled, though by September 2001, only 2,030 cases of fmd—a disease usually only fatal to young animals—had been confirmed.

I don’t think this was merely a preventive cull that went awry. I don’t even think it was panic. While I don’t want to minimize the severity and pain of fmd lesions or the importance of keeping domestic herds free of contagious disease (in the same way I do not shrug at mad cow disease, anthrax, avian flu, tuberculosis, or E. coli), I feel the strongest factors that pushed for such a draconian cull were trade and disease status issues (the UK wanted to regain its fmd-free status as quickly as possible)—and our collective emotional and practical detachment from the species involved.

In other words, the conditions and pressures experienced by our “food animals” have direct consequences for how we deal with epidemics and threats of epidemics. These circumstances not only encourage the spread of disease, they also provide an excuse for us to disengage from the animals and to gaze upon herds and flocks with distaste or indifference. We care for our cats and dogs with increasing devotion and tenderness, but the way we currently go about turning cows and chickens into human food demonstrates that our empathy with animals only goes so far.