The thirty-kilometre Around the Bay Road Race in Hamilton, Ontario, is the oldest of its kind in North America, and each year in March it attracts upward of 5,000 certifiably insane runners who wear finishing medals like badges of honour. If smog and steelworkers come to mind when you think of Hamilton, think again. Think civic pride. Think rabid-about-any-sport fans. In the pre-television era, Hamiltonians engaged in major betting on victors of the race, which began in 1894, two years before the Boston Marathon. In the new marketing era, city officials have erected permanent signposts, one kilometre after the other, along the entire course.

The first two-thirds of the route is flat and fast, but runners then encounter a series of hills that are usually windblown and must be cleared of snow and ice. Four kilometres from the end, they charge down the steep Valley Inn Road. At the bottom, a dwarf named Stan Wakeman—a regular over the last fifteen years—blasts the Queen song “We Will Rock You.” And then comes a winding, 500-metre climb up the other side of the valley. By this point, many runners—eyebrows iced over and noses like frozen taps—start walking. At the top, on York Boulevard, only three flat kilometres remain before the race finishes in downtown Hamilton. Near the end, even seasoned athletes find themselves limping, bedevilled with hamstring cramps. In 1976, the late Victor Copps—then Hamilton’s mayor—attempted to run the race. He suffered a stroke and was unable to finish.

Africans have won the last five Around the Bay races, but its current hero—a man revered by many of the annual contestants—is skeletal, silver-haired, seventy-four-year-old Ed Whitlock of Milton, Ontario. In 2000, for example, finishers who gathered after the race in the Hamilton Convention Centre to wolf down bagels and bananas broke into sustained applause when Whitlock was crowned, yet again, as winner of his age class. Then a youthful sixty-nine, he had covered the brutally difficult course in 1:57:35. Only forty-nine people beat him to the finish line.

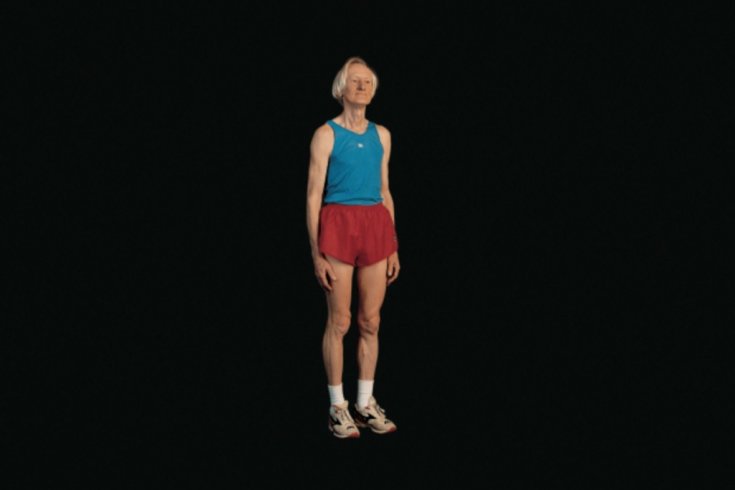

The Around the Bay is for serious runners, and Ed Whitlock—not merely king of this race, but currently the owner of four age-class world records—could be the most idiosyncratic of them all. Most marathoners vary the lengths and speeds of their training runs, and throw in hill and track workouts to prepare for big races, but Whitlock does the same thing day in, day out. He exits his pleasant, two-storey brick home in Milton, just outside Toronto, walks three city blocks, and then runs laps around a 500-metre loop of the Evergreen Cemetery. And this—two or three hours a day, seven days a week (providing that an old Achilles tendon injury does not act up)—amounts to up to 160 kilometres of running each week around a puny cemetery, beside a highway-turned-main-drag in Milton. Down the road, the local Tim Hortons churns out a steady business. A short distance away, a runners’ paradise awaits: rolling hills, isolated rural roads, the Niagara Escarpment. But Whitlock stays put, smack dab in the heart of Anysuburb, Canada, refusing to acknowledge any irony or morbidity when confronted with his own image: an aging speed demon who, thanks to his silver mane and 116-pound frame, looks a bit like a ghost himself, floating sixty to eighty times a day around a graveyard.

During a stroll around his usual training route, Whitlock intones, “A lot of people say, ‘How can you stand the extreme boredom of running around this little loop? ’ Everyone to their own poison, I guess.”

Ed Whitlock is a quiet, modest man who prefers to contain his emotions and excitement about a sport for which he holds several world records. He follows no special diet, having only tea and toast before his morning run, and eschews high-energy drinks or other supplements. He can’t be bothered, either, with stretching, cross-training, or orthotics, and refuses to train with other people. Even Whitlock’s adult sons, Neil and Clive, both runners, have been told not to show up when Dad is training. Clive had the temerity to turn up anyway and run for awhile with the old man recently. “My son Clive came in there while I was running around and ran around with me and I would really rather that he didn’t do that.” Whitlock complained that his son was “always about three paces ahead of me.”

“I don’t like to be responsible for any other person when I run,” he says. “When you run with other people, you have to modify your behaviour to conform with the group, whereas when I run by myself I only have to please myself. I do what I want.”

Whitlock gently refuses to run with me around the cemetery, but he will discuss the world record in his quiet, organized house. A gorgeous print of a sketch by the Italian artist Alberto Giacometti hangs in Whitlock’s front hall. Classical music rises faintly from the stereo. There are few signs—wet running shoes airing out on the front porch, medals and trophies not obviously displayed—that a world-record-holding marathoner lives here.

Born in the London suburb of Surbiton on March 6, 1931, Whitlock grew up in a middle-class family, witnessed the bombings of World War II, studied mining engineering at the University of London, and became a competitive runner in the same era that Roger Bannister was chasing the four-minute mile. In a culture that venerated track-and-field events, Whitlock became a talented cross-country runner and an impressive university athlete, but not a star of international calibre. His fastest mile was about 4:25, far from Olympic speed.

After graduating from university, Whitlock emigrated to Canada in 1952 and worked as a mining engineer in Sudbury, Timmins, Toronto, and Montreal. He married Brenda Collins (still his wife), had two sons, moved up the ranks on the job, but didn’t train or race seriously again until the age of forty-one. He raced well at shorter distances in his forties, but more than twenty years would pass before he would run times that, for his age group, made him an international phenomenon.

Whitlock currently holds thirteen Canadian track records, thirty-three Canadian age-class bests in road race events ranging from the mile to the marathon, and world age-class records for the 3,000 metres indoors, and 5,000 and 10,000 metres outdoors. However, his most significant achievement to date—the one that has made the reclusive and, at times, downright recalcitrant man into something of a media darling—came on September 26, 2004. That day, at the Scotiabank Toronto Waterfront Marathon, Whitlock broke his own world record for men over seventy, covering the distance in 2:54:44. Whitlock is the only man over seventy to have run a marathon in under three hours, the unofficial dividing line between fit runners and the seriously fit. Non-runners may have trouble visualizing Ed Whitlock’s speed. Consider this: most of us over the age of, say, thirty could not run for more than 100 metres at the pace Ed Whitlock maintains throughout an entire marathon.

Ed Whitlock’s world marathon record for men seventy and over will likely stand for a long time. In the near future, it may only be broken by himself, as it appears that he is actually getting faster. The thought of Whitlock inspires other competitive runners to keep training despite the injuries that come with middle age. Whitlock swallows with difficulty and shifts in his seat when faced with this observation. “I’m not a person who is inspired by other people. Therefore, I have difficulty imagining that someone would be inspired by me.”

Organizers of the Rotterdam Marathon, one of the most elite races of its kind, have invited Whitlock to compete in their twenty-fifth anniversary race on April 10, 2005. He has accepted. Although it’s common for race organizers to bolster the prestige of their own events by inviting elite athletes and offering to pay their way, this marks the first time in the history of the Rotterdam Marathon that race organizers have invited an athlete at the master’s level (over forty) to one of their races.

“I am not an enthusiast of air travel. It’s not so much the plane I object to. It’s the airports,” he told me, hinting that the whole international travel ordeal will unfold for him at a pace torturously slow.

Whitlock may feel it ungentlemanly to carry on too much about his late-life running career. He refuses to speak about running in terms of his private dreams and passions, but suddenly reveals a glimpse of the tenacious obsession required to become the best in the world at his sport. He is chatting about the first time he set the over-seventy world record in the time of 2:59:08. It was at the 2003 Scotiabank Marathon in Toronto. Media interest in his story had been building prior to the race, and Whitlock concedes that he felt some pressure to become the first person over seventy to break the three-hour barrier for the marathon.

“It would have been a disgrace to run over three hours. An absolute disgrace,” he says.

In Whitlock’s own mind, it may well have seemed a disaster if he had failed to break the world record that day. But outside the academy of runners, Canadians, on the whole, didn’t know about the world record attempt, or care about the result. They wouldn’t have felt more than a speck of the passion they seem to display, once every four years, when Canadian athletes take to the Olympic track. The only reason that Ed Whitlock is not as familiar to Canadians as Donovan Bailey or Perdita Felicien is that he became a world-record-holding runner when many think older people should be settling into lawn bowling or, worse, giving up entirely and waiting for the end.

Whitlock, for one, doesn’t seem fazed by the ageing process. “As far as I’m concerned, I intend to keep running until something stops me.” For now, Ed Whitlock will keep training for Rotterdam by circling his lonely cemetery.