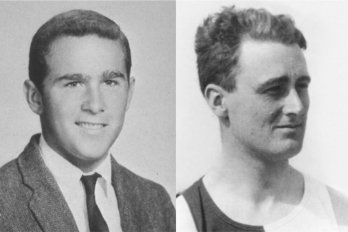

bangkok—At the Copacabana Club, dozens of women in stiletto heels and skimpy skirts sit provocatively behind a plate-glass window, where men order them by number. Up the red-carpeted stairs there are 150 rooms, including party suites with whirlpools, saunas, beds, and framed photos of nearly naked women fondling themselves on sheets of satin. The club’s owner, Chuwit Kamolvisit, has a degree from the National University, in San Diego, loves Elvis, rides a Harley, and rents out women by the hour. Sporting satin shirts and a pencil moustache, he revels in his title as Bangkok’s undisputed King of Commercial Sex.

Although prostitution is officially out-lawed in Thailand, over a hundred massage parlours have operated unhindered in the capital for longer than anyone can remember. Chuwit raked in a fortune at Sea of Love, Emmanuelle, and other deluxe “spas” while police drank in his lobby bars. So he was stunned in May when officers suddenly arrested him on unrelated charges.

Two months later, the forty-two-year-old tycoon held a press conference and demanded to know why he’d been arrested when hundreds of policemen had spent the last decade accepting his generous bribes. Chuwit estimated he’d forked out $2.5 million (U.S.) in extortion fees, imported cars, golf-club memberships, boxing tickets, and home repairs – all to ensure business as usual. “I used to buy whole trays of Rolex watches for police officers,” Chuwit spat. “I used to carry cash in black plastic bags for them.”

Thailand’s prime minister, Thaksin Shinawatra, an ex-cop elected partly on a promise to rid the country of “dark influences,” expressed little dismay at Chuwit’s claims. Thaksin was quoted as saying that underpaid, under-equipped police “may have to get money from the lesser evil so they can go on catching the greater evil.” When the prime minister was a policeman he’d had to pay for his own gun, handcuffs, and typewriter; now he promised to clean up the force with a massive shake-up and improved salaries.

In one of many editorials on the subject, the Bangkok Post stated matter-of-factly that almost every Thai, from the richest businessman to the poorest street beggar, has experienced police corruption. Junior officers supplement meagre wages (as little as $200 a month) by accepting money from drivers who want to avoid a traffic ticket. Street vendors, motorcycle-taxi drivers, and sellers of underground lottery tickets are all able to peddle illegal services because they pay “tea money” to the cops. In Thai, such payments are called suay – which means, roughly, “paying tribute” to people in power. The custom dates back hundreds of years.

Chuwit does not appear excessively worried about corruption, only upset that it stopped working for him. His raucous and sometimes comedic campaign to bring down dirty cops trans-fixed the nation, grabbing front-page headlines for months. At one point his entourage of reporters, supporters, protesters, and bodyguards was large enough to literally stop traffic. One day, Chuwit waved his secret list of one thousand bribe-takers and threatened to name names. “Sleep tight, all police,” he taunted. The next day, he sealed his own lips with masking tape. He invited photographers to watch him pray, posed mockingly in front of a stack of coffins, and carried a placard that read, “May those who do not admit the truth rest in peace.”

At the height of the drama, he disappeared for two days and then re-emerged, dazed and dishevelled, by the side of a road. He held two news conferences in hospital to recount how he was allegedly forced into a taxi by rogue policemen, blindfolded, and kept captive at an unknown location. He later led reporters to the ditch where he claimed to have been dumped, lolling about in the grass to re-enact the scene for photographers. A columnist in The Nation, a Thai daily, quipped that Chuwit was single-handedly raising TV ratings: “We want to know what he’ll reveal next. We want to know if he’s still alive. This is one helluva show, folks. This is reality TV, Thai-style.”

Throughout the theatrics, Chuwit failed to cough up a shred of proof. “I have no evidence, yet everyone in Thailand believes,” he boasted during an interview. “They know I speak the truth.” Bangkok police kept adding to his list of charges – procuring underage girls for prostitution, defamation, fabricating his own abduction. He upped the stakes by dropping cryptic hints before a parliamentary committee on police affairs: “Inspector T” and “Captain S” took regular kickbacks, he said; a “tall commander” owned a stake in two massage parlours; Station “H” had the worst extortionists.

His innuendoes delivered impressive results. Dozens of police officers, including four senior station commanders and the head of a special investigation department, were demoted, suspended, or transferred in disgrace.

Meanwhile, Chuwit is being hailed as a public avenger. At his Copacabana club, he lights up a Mild Seven, settles into a high-backed leather chair, and allows himself a satisfied smile. He may yet go to jail, but he’s savouring the small victories. His new book, The Golden Bathtub, became an instant best-seller. His talk show, Chuwit, Alone and Shabby, was a smash hit. In late September, he launched a new political party.

Chuwit acknowledges that in the West, a man such as he wouldn’t stand a chance in politics. But he reckons he’ll be rewarded for pointing fingers. Thai culture traditionally places great value on avoiding conflict and maintaining Jai Yen – a cool heart. “Thailand needs someone like me,” he says, “someone who is not afraid to talk.”

So far, the promised government “crackdown” on massage parlours has hit only Chuwit. Undercover cops visited his establishments one September night, had sex with several women, zipped back up, then whipped out their badges.

Yet all his establishments continue to operate. Chuwit says that if politicians seriously wanted to ban sex in massage parlours they could simply stop issuing licences to pleasure palaces such as his. But he predicts that both prostitution and corruption will continue to be a part of everyday life in Thailand. You cannot stop people from buying sex, because, he says, “it takes five, ten minutes to do it.” And how can corruption be seriously tackled when almost everybody is involved?