In late summer 2003, Johanny Peña’s baby son was dying of an extremely rare genetic condition when she unexpectedly became pregnant with a second child. A prenatal diagnosis revealed that the unborn female also had the disease, called Niemann-Pick Type A, which is a neurodegenerative disorder caused by an enzymatic deficiency that results in major organ failure and death by age two or three. Peña, who is originally from the Dominican Republic, was offered an abortion but could not bear the thought of terminating her pregnancy. She said, “If God put her there, he did so for a reason.” Doctors at the Hospital for Sick Children in Toronto offered a ray of hope: a cord-blood stem-cell transplant. Peña was told that although the transplant wouldn’t cure the disease, it might delay the child’s symptoms and prolong her life.

Scientists are discovering more and more about the therapeutic value of umbilical-cord stem cells, which contain hematopoietic progenitor cells (hpcs). Cord-blood stem cells have been used primarily, and most successfully, to “regrow” blood in children who have undergone chemotherapy for leukemia and lymphoma, but cord-blood transplants have also been used to treat other blood and genetic diseases in children. (To date, the limited volume of umbilical-cord blood available for therapeutic use means it has not yet been widely used for adults, who require larger doses.)

Umbilical-cord stem cells are now a viable and, for infants and children, often preferable alternative to transplants of bone marrow, which also contains hpcs. The human leukocyte antigen (hla) match between donor and recipient need not be as exact, and there are fewer cases of rejection. Stored cord blood is more readily available than bone marrow, which in most cases must be extracted in a surgical procedure at the time of transplant. Unlike bone-marrow donation, the collection of cord blood is painless: it can be collected in utero, during a Caesarean section or after a vaginal birth, with minimal risk. In the United States, Europe, and Japan, more cord blood than bone marrow is used for childhood transplants.

Three months after she was born, Francheska Peña became the youngest person with Niemann-Pick Type A to undergo a cord-blood stem-cell transplant in North America. Matched cord-blood cells had been obtained from a public cord-blood bank outside Canada, and the girl’s mother, now twenty- eight, is grateful to the anonymous donor. Franscheska’s regrown blood has normal levels of the formerly missing enzyme, and although her health remains fragile and her development is severely delayed, she has outlived her brother, who died before his second birthday.

If this sounds like a success story, one key fact is being overlooked. Peña’s doctors had to turn to another country to get the life-saving cord-blood stem cells because, unlike many other developed countries, including the United States, Canada does not have any large public-access, taxpayer-supported cord-blood banks. Instead, policy-makers have stood by while the collection and “banking” of this valuable resource has been commercialized, with parents who can afford it paying around $1,000 plus a yearly fee of over $100 to store their child’s cord blood. Upwards of 40,000 cord-blood samples are stored privately in Canada—approximately twenty-five times more than are stored publicly—and they are only available to immediate family members.

The chance of a family with no known risk factors needing this blood is remote. Dr. John Doyle, a pediatric hematologist at the Hospital for Sick Children, says that only about 1 in 150,000 families will use the cord blood they’ve paid to store if there is no diagnosed cancer in a sibling and no known metabolic disorder in the family. (Doctors can put families with children at serious risk in touch with private banks, which will usually waive initial costs.) Meanwhile, every year Canadian children who need transplants from an unrelated donor die because a match cannot be found.

The commercialization of cord-blood banking is striking in a country whose blood-supply system is based on the principle that blood is a public resource. Blood donations are voluntary and represent citizens helping each other and the community. Private cord-blood banking also stands in sharp contrast to Canadian practices and policies around other transplantable human tissue. Canada has long-established, publicly supported tissue centres, where donated skin, corneas, and heart valves are available to surgeons and their patients.

Umbilical cord-blood banks, which are just over a decade old in Canada, have set up business during a period of strong federal support for the commercialization of research. The Toronto Cord Blood Program, a public bank established at Mount Sinai Hospital in 1996, morphed into Mississauga-based Insception Biosciences, a private banking and research company, in 2004, a move facilitated by the hefty investment of venture capital. Insception, which is promoted on an Industry Canada website as a biotechnology success story, and Lifebank Corporation, a publicly traded company located in Burnaby, British Columbia, along with at least ten other smaller private banks in Canada, dwarf the country’s only two public initiatives: the Alberta Cord Blood Bank, a non-profit bank established in 1996 and plagued by uneven support, and the fledgling Héma-Québec bank, launched in 2004, which has stored only about 300 units to date.

Canadian commercial banks market themselves aggressively to expectant parents. Lifebank distributes thousands of cord-blood brochures to expectant mothers in prenatal kits distributed by Z Retail Marketing, which specializes in cross-marketing “leading Canadian women’s clothing retailers and prestigious health and beauty products.” Insception holds information sessions in Toronto hospitals with maternity wards. Françoise Baylis, a bioethicist at Dalhousie University and co-author of Canada’s original stem-cell guidelines in 2002, confirms that private storage in cases where there are no known risk factors is “extremely expensive insurance for an unlikely event,” but notes that private banks often hard sell their services using the rhetoric of being a good parent.

Lifebank and Insception market themselves to parents not only on the basis of current treatment realities, but on the notion that cord blood may soon offer biological insurance against a whole host of diseases. “Extraordinary new uses for stem cells are currently under investigation and the possibilities are endless,” enthuses Lifebank’s website. Inception submits that “scientists are actively testing the potential for using stem cells to treat such diseases as leukemia, Parkinson’s, heart disease, diabetes, multiple sclerosis, stroke and spinal cord injury.” But according to professor John Dick of the stem-cell biology program at the University Health Network in Toronto, “you are into never-never land” with such claims. “Sure, there is promise, hope, all those kinds of things. But there is a huge amount of biology that is unknown,” he says. Dr. Martin Champagne, who works at l’Hôpital Sainte-Justine in Montreal and has performed more cord-blood stem-cell transplants than any other Canadian surgeon, is also cautious about future applications of the treatment: “A few years ago, we were enthusiastic about gene therapy. Now it’s stem cells. But there is a lot of scientific uncertainty.”

The fact remains that cord-blood stem cells are a proven lifesaver, particularly for children who have been treated for cancer. Three years ago, it was Champagne who urged Héma-Québec, the province’s counterpart to Canadian Blood Services, to establish Canada’s only comprehensive publicly supported cord-blood bank. “I don’t know why there is not more interest in cord blood in the rest of Canada,” he says. More than one-third of terminally ill Canadian children who needed transplants from an unrelated donor could not find a match in 2005, reports Dr. Lothar Huebsch, former president of the Canadian Blood and Marrow Transplant Group. Huebsch estimates that each year, a matching source of hpcs from an unrelated donor cannot be found for between fifty and seventy-five children (and more adults) with acute leukemia, most of whom die from their illness. (The best source of hpcs is an hla-identical sibling without the disease, but only about a quarter of those who need transplants have such a sibling.)

A large supply of publicly banked cord blood would significantly improve the odds that children in need of a transplant could find a suitable match. The Society of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists of Canada supports public banking, stating in their 2005 clinical-practice guidelines that cord-blood stem cells “have greater potential as a collective asset than as an individual asset.” The guidelines go on to recommend that eligible pregnant women be encouraged to consider public cord-blood donation by their prenatal providers. Currently, doctors estimate that less than 1 percent of cord blood is banked in Canada; most is simply discarded.

Importantly, routine umbilical cord-blood collection would mean the banked blood would match the genetic heterogeneity of the population. What’s more, a large Canadian cord-blood bank could, because of the diversity of the population, be a resource for the rest of the world, according to Dr. Paul Caulford, head of family medicine at Scarborough Hospital, which services people from more than ninety different countries of origin.

The United States already has twenty-two large public cord-blood banks, and Congress recently allocated $12 million (US) to establish a national cord-blood inventory and help build a public stock of 150,000 cord-blood units. This initiative came in the wake of a landmark 2005 report from the Washington, DC-based Institute of Medicine, which provides expert advice to the government and the public. The report concluded that by increasing the size and quality of the cord-blood inventory, nearly 90 percent of all patients who need a transplant should be able to find a suitable hla match in either the bone-marrow or cord-blood inventories—three times the number who find unrelated donors in the United States. In fact, as doctors and advocates have repeatedly pointed out, Canada lags behind much of the developed world on this issue.

Canadian Blood Services, funded by the provinces and territories (excluding Quebec), is the obvious body to set up a national public cord-blood bank. Indeed, the deputy ministers of health have asked cbs to assess the need for, and costs of, establishing such a bank. Presentation of a feasibility report, originally scheduled for last year, has been delayed until probably the middle of this year. If the report recommends a national bank, and the provinces and territories agree to fund the project, it will take time to get it established and build up inventory. (Héma-Québec was able to act relatively quickly because only one province is involved; national health initiatives and reforms in Canada are often slowed or stymied by the need for agreement among the provinces.)

For the foreseeable future, then, Canadians outside of Quebec who want to donate to a public bank have essentially one option, the Alberta public bank, and transplant surgeons will continue to rely on other countries to obtain cord blood. This means that some patients who need hpcs from an unrelated donor—those who aren’t as lucky as Francheska Peña in finding a match—may well die waiting.

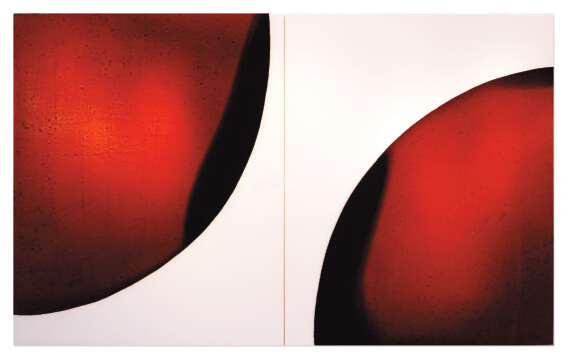

Vehicle 1 (2006)

Vehicle 1 (2006)

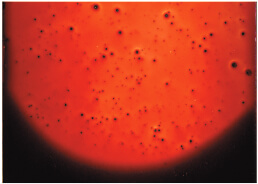

detail from Phase (2006), blood preserved on white plexiglas with multiple layers of clear resin with UV coating

detail from Phase (2006), blood preserved on white plexiglas with multiple layers of clear resin with UV coating