I am a wriggling, water-borne spore. My life depends on how vigilantly I navigate treacherous currents full of predators. I chase drifting morsels of decaying flesh (my food), and kill off rivals (for what their brains, when consumed, might unlock in my own consciousness). For a scavenger like myself, these are inspiring waters, and after a few minutes of bottom feeding I advance up the food chain. Now I am a trematode, one of those ghastly liver flukes you get when you drink from the banks of the Mekong River. I look like a cartoon hot dog with eye stalks and tusks.

These are the early stages of my life in Spore, Will Wright’s sprawling interplanetary video game, released last fall, in which almost everything in the game’s universe is an interactive, customizable element. The game was inspired in equal measure by the theory of evolution and Star Trek, and the choices my creatures make at the beginning determine what kind of civilization I can create later, so that my vegetarian, politicking tribe of yellow-spotted ostrich pigs progresses in democratic parity with rival species, sharing knowledge and tools, while my scorpion dogs roam their world in gangs packing stone axes, fire sticks, and spears; they raze nearby villages and steal the inhabitants’ tools, ideas, and dna.

At every level of my spore’s evolution, I get to design my own tribe, city, planet, all the way up to, as Wright puts it, playing strategy games in a “toy galaxy.” At the cosmic stage, I can begin to farm planets and terraform dead moons. I become a panspermic gardener seeding meteors through the atmosphere of lifeless planets and waiting for life to grow up so I can abduct and crossbreed species from different planets and start a new civilization in a neighbouring star system. It’s a vertiginous climb up the evolutionary chain from liver fluke to galactic poacher, but I believe I’ve stayed true to my roots.

Spore is an evolutionary extrapolation that miniaturizes the chaos of eons into hours of fun. I am the fickle overlord of a lively galaxy; I plant civilizations and control their inhabitants at will. But even when I’m a lonely scorpion dog on the hunt for nothing other than flesh to eat and one of my species with which to mate, I can’t help but wonder at the intelligence behind what I’m seeing—the colossal algorithmic undercarriage that creates the game’s illusions. I can’t see it, but I know it’s in there: millions of lines of proprietary, top secret code. I marvel at this computational madness, not because I presume Spore has more code than, say, one of the games based on Tom Clancy’s novels, but because Spore is a game about creating life and manufacturing reality. Proponents of intelligent design might have accidentally found in Will Wright their greatest educator. Once I possess all the skills I need to operate an entire planet, I can instantly become a god.

That he draws on both creationism and evolution isn’t surprising, because absurdity, irony, and satire are a part of Wright’s style. In his own very Sporian definition, evolution is an “interplay between competition driving cooperation, driving specialization, which then brings the competition to the next level.” But I believe it was Roddenberry, not Darwin, who asserted that every species will one day fly a spaceship. So far, three of my five personally designed species own craft capable of travelling at the speed of light, and I don’t expect my other two creatures will veer off to become burrowers or marsupials. I’m certain that all my avatars will one day meet in outer space.

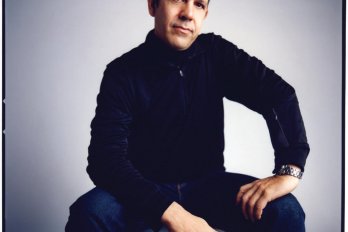

It took Will Wright seven years to complete Spore, which sold more than a million copies in the three weeks after its release. This was entirely predictable. In 1989, he released SimCity, in which play-ers assume the role of architect, urban planner, real estate developer, unelected mayor, and Jane Jacobs, and it was an immediate success, positioning Wright at the top of the video game food chain. Maxis, the company he started with his partner Jeff Braun, has gone on to create more than two dozen Sim games, including the highly addictive SimTower and the bad-dream-giving SimAnt, as well as SimFarm, SimSafari, and Sim-Health—all in addition to the blockbuster Sims series, launched in 2000 and now in its third and most ambitious iteration. In Wright’s new game, Sims 3, released this month, your avatar is free to leave the compound that limited its movement in Sims and Sims 2, so an entire neighbourhood is now yours to survey, manipulate, and obsess over.

Video games are poised to outsell movies, and in the gaming world nothing sells like Sims. The franchise has grossed over a billion dollars; there’s talk of a live-action Sims movie; and every new launch propels Wright out on the lecture circuit, where he talks about his creations with the soft, methodical, flawless articulation of a high school chemistry teacher who explains what panspermia means before teaching you how to make crack cocaine.

In the year of Pong, the legendary first-generation video game launched in 1972, Will Wright is twelve. The Wrights live in Atlanta. His father, Will Wright Sr., is the successful inventor of a packing material. His father and grandfather were both engineers who graduated from Georgia Tech. Like his dad, young Wright likes to take things apart and build things from scratch. Wright found that as a child he flourished best in a local Montessori school that encouraged freethinking and praised creative problem solving. Instead of following his father straight into the world of engineering, he went to the New School in New York and built a robotic arm, then dropped out to play video games and design his first, a million seller called Raid on Bungeling Bay. Summarizing his career for New Yorker writer John Seabrook, Wright said, “SimCity comes right out of Montessori—if you give people this model for building cities, they will abstract from it principles of urban design.” When other games were copying Mario Bros. , Wright started his career inspired to make games out of Erector Set and Lego. His interests have always seemed to combine equal parts childish delight, adolescent fantasy, and complex thinking—your Sims 2 avatar is reading the newspaper on the toilet, and Wright studied Abraham Maslow’s 1943 paper “A Theory of Human Motivation” to get you there.

Wright describes the worlds he creates as “metaverses,” a synonym for virtual reality drawn from Neal Stephenson’s 1992 science fiction novel Snow Crash. It’s the book that put the word “avatar,” meaning our digital proxies, into the mainstream. Its hero is an avatar named Hiro Protagonist. “So Hiro’s not actually here at all,” Stephenson writes. “He’s in a computer-generated universe that his computer is drawing onto his goggles and pumping into his earphones. In the lingo, this imaginary place is known as the Metaverse. Hiro spends a lot of time in the Metaverse. It beats the shit out of the U-Stor-It.” Which is where Hiro’s owner lives: in a storage box.

Snow Crash was to the science fiction of the 1990s what the late David Foster Wallace’s 1996 novel Infinite Jest was to metafiction: a new satirical frontier. In the former, Snow Crash is the name of a virus that kills both the online avatar and its human host. In the latter, Infinite Jest is the name of an underground movie so amorally entertaining that viewers are instantly addicted, watching repeatedly until they become incontinent and die. When the wife of the first victim finds her husband dead in his recliner, she rushes over, “crying his name aloud, touching his head, trying to get a response, failing to get any response to her, he still staring straight ahead; and eventually and naturally she—noting that the expression on his rictus of a face nevertheless appeared very positive, ecstatic, even, you could say—she eventually and naturally turning her head and following his line of sight to the cartridge-viewer,” where the deadly Infinite Jest was playing.

If Stephenson’s Snow Crash or Wallace’s Infinite Jest were to appear in a literal form rather than a literary one, it wouldn’t be a virus or a movie; it would be a Will Wright video game.

Wright is an artist in the mould of a Jim Henson or a Dr. Seuss. Both successfully combine mass entertainment with complex moral lessons that work for young and old alike. Sims lets children play at being adults in a version of the real world populated by avatars who lose their jobs, find religion, and go crazy. In Sims, it’s hard to stay friends, it’s hard to remember to eat well, it’s hard to get enough rest, it’s hard to pay the bills on time, and find time to study, and do all the chores, and look after the kids. It’s just like adulthood!

My avatars are all of the Kermit genus, with soft contours and bright colours, capable of floppy and floppier gestures, which even at their most gnashing and bloodthirsty are totally non-threatening. Sims lets children and adults examine the consequences of behaviours they may not have experienced in real life. What if I don’t do the dishes? What happens if I flunk out of school? What happens if one person in the family gets all the attention? What if I become a hazardous drunk, or have seven children, or throw a party on Sunday night at three in the morning just to see what happens? What makes playing Sims novelistic is the sensation of igniting fate—of watching as one small choice sparks a whole chain of events. And by reducing all of life’s decisions to a mouse click, Sims allows us to see how many little things we must do to keep the stitching of our lives together.

It’s not in the verisimilitude of his detail that Wright achieves realism; his imagination is too driven by pop culture to follow a straight Raymond Carver or John Cheever narrative. But a Sims life can start to resemble, in its absurdity, a story by Rick Moody or Amanda Filipacchi. Sims has made kitchen-sink minimalism the most popular genre in the video game industry. Everything we do in Sims, like taking care of children, doing chores, making dinner, disappearing into our work, hosting parties, is what video games are meant to relieve us from. Is Sims just another way for us to neglect our duties in our real lives? It still seems improbable that after eight years a game about doing the things we groan about all day is still so popular.

But this is what makes Sims so addictive: it feels like a legitimate way to examine our lives, even if we’re aware of its infinite jest. In Sims, learning to

do the dishes is enjoyable. Green fumes rise from plates of food that have sat out too long; I click my mouse, and they’re gone. But for every achievement I make in Wright’s Metaverse, I am reminded of something I’ve failed to accomplish in my own. Sims is constantly reminding me how important it is to pay attention to these little things, but it’s so much fun ignoring them.

Wright’s next move with Sims could be to improve the psychological detail. Novels don’t need action; their unique strength is in mapping the psychological landscape. While Sims has novelistic potential, the game’s roots are still in theatre and sport, and might always be. But what would it be like if Wright were to turn his attention to a study of the human mind and make a bestselling game out of Sims neuroses?

Unlike most video games, Wright’s require players and their creations to interact cooperatively. But as much as I see communication as a key to the survival of my vegan super-race in Spore, I also recognize that there are other spe-cies, like my carnivorous interplanetary pirates, whose rule is based on violent oppression, demagoguery, and greed. In fact, most of my Spore creatures do things I wouldn’t endorse, like fighting another species to extinction. And if I care to look closely at my Sims avatars, I can see that they are sex obsessed and chore averse and financially labile. What does this say about me, us, Will Wright? And, more important, what does it suggest about the future? Imagine when Spore and Sims begin to conjoin and the game goes massively multi-player online, so that communication is actual and virtual economies flourish, and wars between species and galaxies exist in real time, and the equivalent of a url could take your avatar to a sleazy, Mos Eisley–like nightclub where you might meet a hot avatar, an avatar who might turn out to be that “special someone,” and you can’t help but think it’s ironic that you first made contact on a distant planet you intended to detonate.