Earlier this year, the New York Times released their list of “The 100 Best Books of the 21st Century.” The splashy interactive project was equal parts listicle and ballot, inviting readers to select the titles they’d read and generating an instantly viral personalized graphic that testified to their taste. (I’ve read 41, mine said flatly, a lower figure than I’d been expecting.)

In a section on methodology, the New York Times Book Review explains that staffers “sent a survey to hundreds of novelists, nonfiction writers, academics, book editors, journalists, critics, publishers, poets, translators, booksellers, librarians and other literary luminaries,” asking each of them to pick their ten best English-language titles published in the United States in the past twenty-five years. Staffers kept their definition of best hazy on purpose—it could mean a reader’s favourites, or it could mean the works of literature they thought were most likely to endure. Then, a second (and optional) round pitted two random titles against one another and asked the respondents to choose between them.

Within these restrictions, literary fiction was heavily favoured. Of the top ten titles, only one—Isabel Wilkerson’s The Warmth of Other Suns, a researched epic about the Great Migration—was not a novel. The next nonfiction title to appear, Joan Didion’s The Year of Magical Thinking, clocked in at number twelve. Nonfiction made a decent showing overall. Staples of literary journalism, like Patrick Radden Keefe’s Say Nothing and Adrian Nicole LeBlanc’s Random Family, cracked the top thirty. But underrepresented on the list, among a few other genres, was memoir.

Apart from Didion’s, there were only six other personal narratives in total. This number is debatable depending on where one draws the lines: I did not count, for example, Ta-Nehisi Coates’s Between the World and Me but did count Maggie Nelson’s The Argonauts; while both books have personal and cultural components, only the latter was marketed as a memoir. But however one defines the form, the total hovers near a handful, give or take. This paucity of first-person storytelling is striking. Among the best writing of our current century, have so few people written well enough about their lives to qualify? Where are all the memoirs?

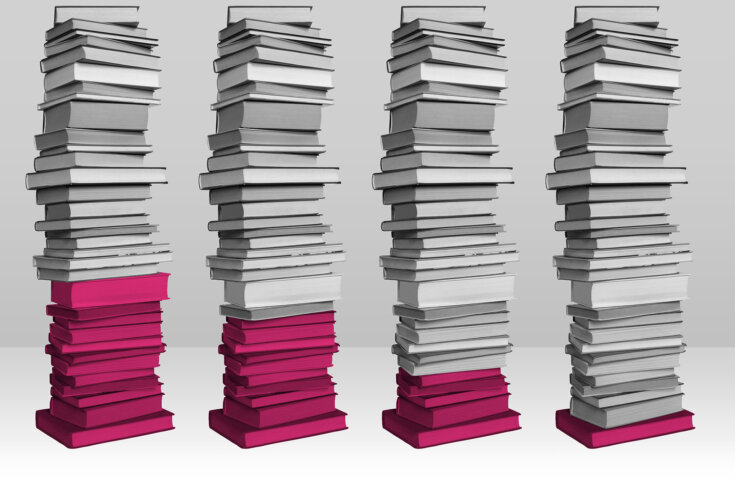

One might also ask this question when surveying recent bestsellers. At the time of writing, all the top memoirs on the New York Times Best Sellers list for hardcover nonfiction were by celebrities and politicians—Ina Garten, Hillary Clinton, an actor who was on Gilmore Girls. The lack of memoir isn’t just the result of a genre popularity contest. It’s an actual numerical decline. In a post on Brevity Blog from earlier this year, Allison K. Williams and Jane Friedman look at the number of book deals for memoirs in the US in the past three years. Using data from Publishers Marketplace, the industry database that reports on trade news and book deals, the authors share that more than 1,800 fiction books were sold in the past twelve months, while the number for memoir deals was lower than 300. In fact, over the past three years, the total of memoir manuscripts bought by publishers—including what’s usually the safer bet: books by celebrities—has actually fallen. Though there will often be a few personal stories, even by non-famous people, that end up being some of the year’s biggest books—think blockbusters like Tara Westover’s Educated or Cheryl Strayed’s Wild—writers who want to enter the genre face an uphill battle.

Within the publishing industry, it’s become a truism that memoir is difficult to sell. I hear it anecdotally from my friends who are trying to find a publisher to buy their books, and even from the editors who hope to acquire them. Memoir is “so hard right now.” In an Instagram post from earlier this year, literary agent Carly Watters addresses this perception directly. Across a carousel of slides, Watters identifies some of the pitfalls facing would-be memoirists. Many of these problems coalesce around a story being too internal—while it may be the cathartic expression of a deeply personal experience, there is not enough material there to be of interest or value to a reader. A successful personal story, Watters says, must have two key elements: accessibility—a way into the story that readers “understand and can believe”—and, the trickier one, unbelievability—“the sense that [the writer’s life] is so unlike our own lives that we are wildly curious about [it].” Tacked onto the end of the second criterion, almost like an afterthought, is that this accessible, unbelievable story should also be “very well told.”

Plenty of books do this. And still it doesn’t seem to be enough to give the memoir genre a more muscular presence in the literary landscape. Readers seem to reach for these books less—which is presumably why fewer of them are being acquired for publication. Why are we so bored by one another’s lives? One explanation Williams and Friedman offer is the idea that, while genres have fans, memoirs are a weird exception to this rule. Nobody is “a fan of memoir,” they suggest; instead, they are a fan of an author and their body of work. I’m not sure I buy this explanation, which seems to disregard the inherent pleasures of the genre, which aren’t all that different from the joys of reading fiction: immersion in the architecture of another mind, or a writer’s attention to language, or a sense of narrative propulsion. Perhaps another reason for readers’ memoir fatigue is that we’re inundated with what happens in other lives already. We get enough material from social media feeds, TikTok “Get Ready with Me” videos, and viral personal essays—a form that endures, despite repeated claims of its death. Maybe people feel they don’t need to go looking for more.

But some of us do. In these explanations, one factor that feels strangely neglected is the how of the telling. Maybe the real difficulty facing memoir isn’t that the bar is being winched higher and higher, but the opposite. With all this emphasis on the contents of the story—that it be serviceable to the point of literal disbelief—the form in which it’s told falls by the wayside. If you boil them down to single-word subjects, spectacular books like Melissa Febos’s Girlhood and Leslie Jamison’s Splinters tackle ostensibly unspectacular experiences—femininity, divorce. But it’s the elegance and particularity of how each story is told that puts both books at the height of the genre and continues to stoke my hunger to read memoir at all. I love the genre because I like to see how people try to tell the story of their lives, rather than the specifics of what happens as those lives are curated for me.

A number of literary strategies have evolved to make memoir feel more relevant to a reader. One way of reading the subgenre of personal nonfiction that also traffics in criticism or pop culture—that “braids personal narrative with cultural criticism,” as such books often promise in their jacket copy—is that it’s an attempt to make more people care about a life other than their own. If readers can’t be moved to pick up a book because of who wrote it, or even the events the writer lived through, maybe they’ll be hooked, instead, if it comes with a tour through pop culture touchstones they already know and love. This has been both a boon and a liability to the genre. A lot of books shuttle capably between first-person writing and engagement with cultural-critical sources and are made more powerful for having staged the encounter, like Jia Tolentino’s Trick Mirror or Cathy Park Hong’s Minor Feelings. But it’s a move that, when done uncarefully—as it sometimes is—can feel to the reader like being woken from a dream or force-fed a vegetable.

Such formal Frankensteining is a canny move to try and leverage a larger audience. It makes sense when you look at the bestseller lists, where most of the nonfiction titles are about things rather than people. They’re big-ideas books about subjects like politics and history and tech. But memoir has to be able to find an audience without always needing to be dressed up as something else. Personal stories, even ones that aren’t explicitly blended or braided with outside sources, do open up onto bigger social questions. Doing that is part of the memoirist’s job, and I suspect it’s also part of what draws readers to the genre. Whether publishers understand that this is part of the books’ appeal, and not a weakness the reader needs to be distracted from perceiving, is unclear.