ARTS & CULTURE / SEPTEMBER/OCTOBER 2023

The Legacy of Saskatchewan’s Most Controversial—and Impactful—Artist Program

The infamous Emma Lake Artists’ Workshops were ad hoc, low budget, and falling apart. They also reimagined the possibilities of art

BY LEE HENDERSON

Published 6:30, Sep. 28, 2023

To get to Emma Lake, follow the number 2 north out of Prince Albert for thirty minutes before pulling a hard left onto the 263. It’s a stunning drive through super-flat Saskatchewan, a dramatic voyage through the abstract quilt work of wheat and canola fields until you pass the unmistakable threshold into Canada’s boreal forest. Ten more minutes through cabin country and Emma Lake is waiting among the poplar woods and mosquito-infested muskeg on the other side.

The lake itself stretches north in three parts. The northernmost section, “Big Emma,” is tranquil thanks to a lack of development, while the southern and central portions offer campgrounds and summer cabins. The waters are filled with pike, walleye, and white sucker, and visitors may see beavers swimming around Cattle Island or black bears foraging at dumpsters. On clear summer nights, the sky can show crackling waves of green and orange. It’s here that, beginning in 1955, painters Kenneth Lochhead and Arthur McKay first coordinated the Emma Lake Artists’ Workshops, where artists would gather and share and create. Or at least they used to, in the old days.

Every August, the organizers invited guest artists from New York or some other faraway place for a weeks-long intensive where the outsiders were tasked with mentoring a dozen or two of their peers. And as artists made the pilgrimage summer after summer, the results would come to define prairie art in the twentieth century.

Emma Lake received a modest budget from the University of Saskatchewan and the province’s arts board in 1955, but the mandate was to invite working artists, not students. And Emma offered nothing of a typical education. There was no structure or oversight for the studio from one mentor to the next. In fact, the mentors were under no obligation to do anything at all. When researcher John King interviewed McKay for an oral history of the Emma Lake Artists’ Workshops—which offers one of the only comprehensive accounts of the early years—and asked why they started the program, McKay answered that they felt Saskatchewan “was a highly under-stimulated area; like, nothing was happening. It was far away from everywhere. We didn’t see any original things and the University provided very few grants for travel—so the only answer was to bring people here.”

Among the guest mentors were some of the most radical—and polarizing—figures in modern art, including Clement Greenberg and Barnett Newman. They inspired locals to consider new techniques, new styles. Some artists took to the challenge, while others bristled at the presumption of an outsider deciding how they should approach their work. According to some critics, these outsider voices even remade the region’s style in their own image. The debate continues, but many can agree that for the nearly six decades it survived, Emma Lake succeeded in creating as much conflict as history.

Emma lake was always the wild younger sister to its sibling in the mountains, Alberta’s Banff Centre for Arts and Creativity. By 1955, the Banff Centre had already been active for twenty-two years and was establishing itself through a mix of theatre, music, and studio arts programming. Unlike the rock-solid infrastructure that developed at Banff, with its enviable library, acoustic performance hall, civilized dining room, and fitness centre, Emma Lake was forever ad hoc, falling apart, and at risk of being cancelled. Banff supports artists; Emma Lake, with its uninhibited water energy, seemed to test them. “The terrible little cottages were most uncomfortable and gloomy and damp,” said painter Robert Bruce, who attended in 1959, according to King’s oral history. “And when we got to the studio, it was raining and the roof leaked. We had a symphony going with all the tin cans and bottles collecting drips.”

But what Emma had was talent. The watershed year was 1959, when New York abstract painter Barnett Newman was invited and his avant-garde ideas immediately began working their way into Saskatchewan’s artistic identity.

Newman was gaining critical favour for the meditative paintings of vertical stripes that he’d been making since 1948—he called them “zips”—which he used to explore our experience of colour. It was an approach to abstraction and picture making that was perfect for Saskatchewan and its swaths of yellow wheatfields, green grasslands, and never-ending blue skies.

But when the organizers invited Newman, they had no idea what effect his visit would have on local art. “We had read an article by Eugene Goosen [sic] in the Art News of Barnett Newman’s having a show,” McKay explained to King. “We read the article and thought: Why not? . . . Up to this time, we knew nothing about Newman, so our choices were based on intuition in those days. It was a time when intuition still had free play; in institutions, intuition doesn’t have free play.”

“[Newman] seemed to unlock the potential within us; we were ripe for it,” said painter Ted Godwin. Roy Kiyooka also attended Emma Lake that year, and it came about at a pivotal moment in his development. “I don’t know whether Barney helped to unlock the potential within us,” Kiyooka said chiastically, “but I do know that he helped us to unlock that potential within us.”

Still, art is a messy process. “If the Newman was a ‘peak,’ then I’d sure hate to be there at the bottom,” Robert Bruce told King. He wasn’t won over by the mentor. “As far as I was concerned, [Newman] contributed absolutely nothing artistically.”

But the before-and-after is clear. It was even on display during Ten Artists of Saskatchewan: 1955 Revisited, a recent exhibition at the MacKenzie Art Gallery in Regina. Curator Timothy Long restaged an original 1955 exhibition that served as a survey of Saskatchewan’s leading settler artists during its jubilee year in Confederation. As a vision of art before Emma Lake, it’s enlightening.

Both Lochhead and McKay are featured. Rather than the abstraction they later became known for, their paintings here veer toward surrealism and impressionistic styles. Reta Cowley’s paintings from 1955 are also present: edgier, more urban, and more pictorial than her later landscapes, which have a luminous abstract quality to them. Like Cowley, one of her art teachers, Dorothy Knowles has become widely recognized for her prairie landscapes. Born in Unity in 1927, she died this past May, at ninety-six, after an impressive career exploring light and colour in prairie nature. In 1955 Revisited, we see one of her earliest pieces and can compare it to her mature work.

Roses is a laboured and self-conscious still life of a ceramic vase of fresh flowers set indoors; it lacks not only the spontaneity of her outdoor pictures after Emma Lake but also her later compositional rigour. Knowles would later come to define the Saskatchewan landscape just as one might see that Georgia O’Keeffe captured something essential about New Mexico or how Claude Monet made the Seine his own. But we don’t see that in the 1955 show. We see familiar names but not the kind of picture that would be integral to Saskatchewan’s art identity. To understand the leap, all roads lead back to Emma Lake.

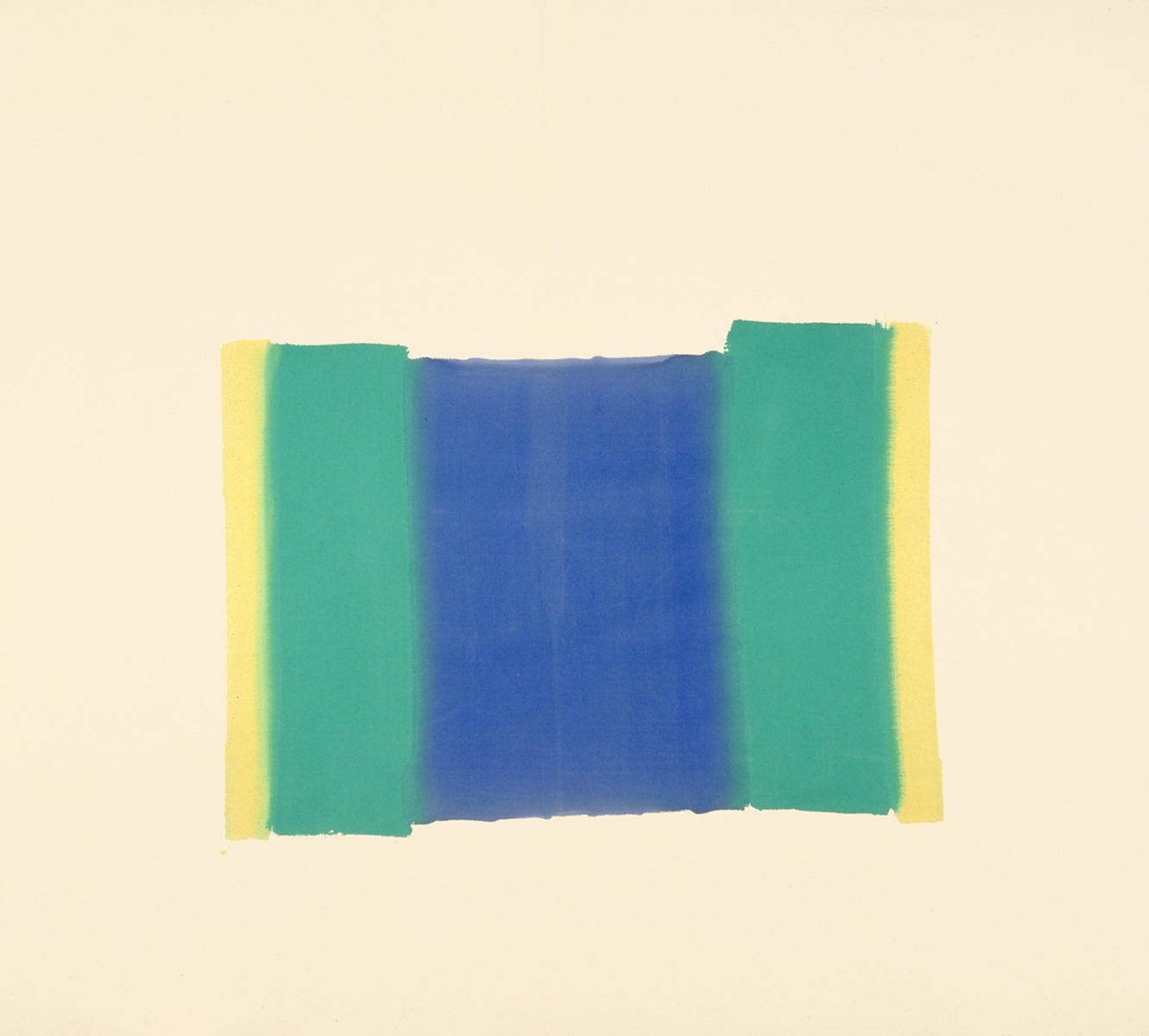

The most pivotal moment of the workshops was the arrival of Clement Greenberg. A bold and controversial New York art critic still famous for his 1939 essay “Avant-Garde and Kitsch,” and in part responsible for Jackson Pollock’s status in American art, Greenberg actively supported artists who shared his ideas about paintings—those who sought in picture making what he called “the ineluctable flatness of the surface.” No illusions. His preferred style was nothing like the emerging postmodernism or early strains of pop art of the time but a much more formal approach that he saw as the rightful heir to the modernist avant-garde and “an authentically new episode in the evolution of contemporary art.”

He rewarded those who felt the same. He chose some of his acolytes in his survey of prairie artists for Canadian Art magazine in 1963. More importantly, he picked works by both McKay and Lochhead as well as by two Emma Lake mentors, the American painters Kenneth Noland and Jules Olitski, for his exhibition first held at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, in which he sought to define the generation after Pollock with the title Post Painterly Abstraction.

John Coplans’s review in Artforum sums up the exhibition: “Abstract Expressionism was loose; the new style is tight. Abstract Expressionism revealed brushstrokes; the new style conceals them. Abstract Expressionism used thick paint; the new style uses thin paint. Abstract Expressionism was dense and compact; the new style is clear and open. Abstract Expressionism used accents of dark and light; the new style employs color.”

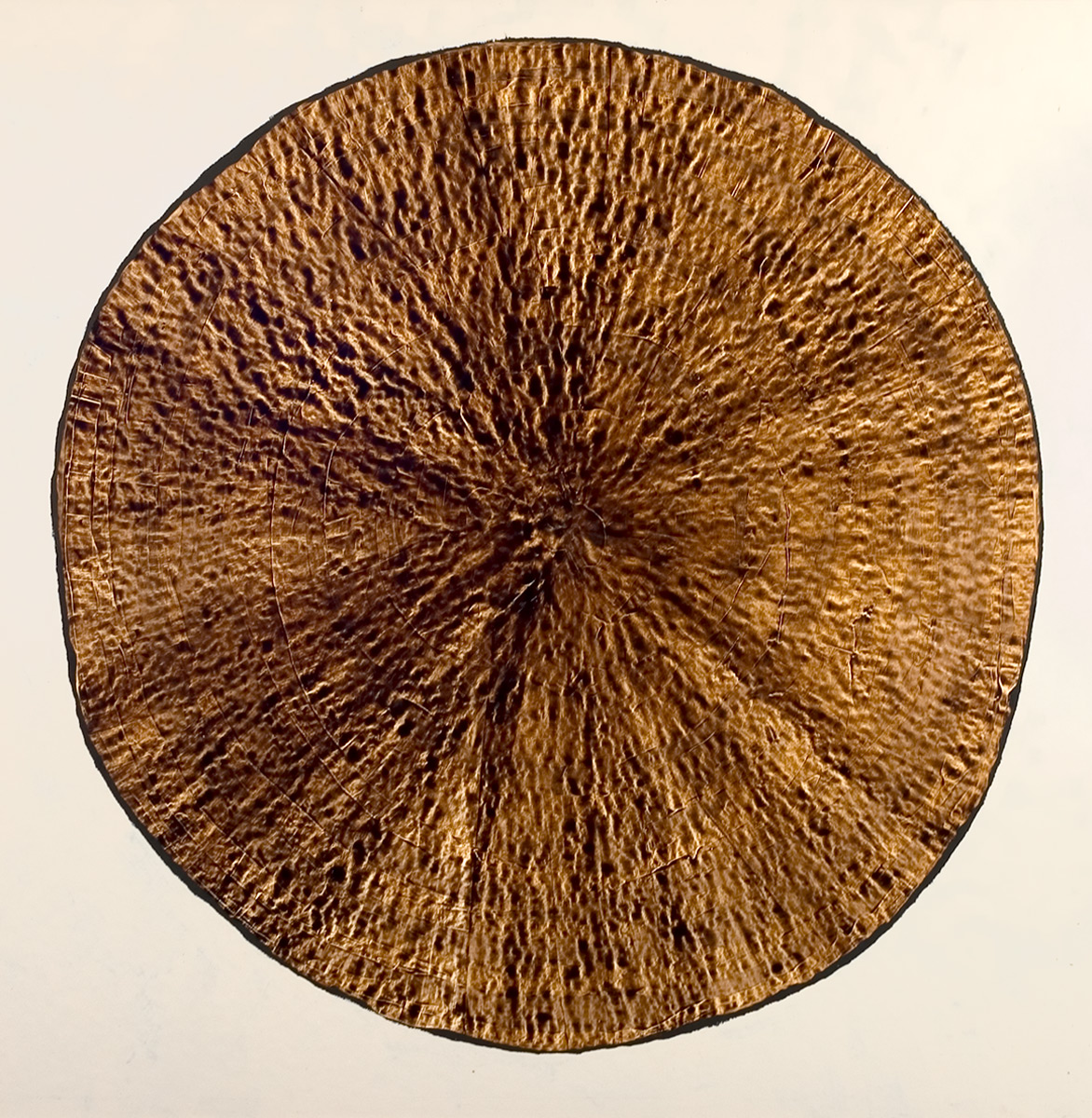

This style became associated with the “colour field movement,” or “hard-edge abstraction,” and it came to dominate in Saskatchewan. For decades, critics, curators, collectors, and artists associated Greenberg’s visit with the province’s enduring identification with the style, which stuck around in certain areas even after it had long gone out of fashion elsewhere. From the 1955 Revisited show, Knowles, Cowley, McKay, and Lochhead, among others, would be associated with this movement. We see, for example, McKay’s practice develop from an impressionistic big-sky, little-town landscape in 1955 Revisited to variations on Greenberg’s flatness with minimalist paintings like Circle and Enigma, both selected for the Post Painterly Abstraction show in 1964.

“You have no idea of how much I’m betting on Saskatchewan as N.Y.’s only competitor,” Greenberg wrote to Lochhead in 1963. High praise, but Greenberg lost his shirt, we must admit.

The prairie art scene is contrarian and skeptical through and through, and no acclaim goes without some side-eye. Ronald Bloore, a remarkably fluent abstract artist, noted in a 1964 Canadian Art article that the workshops “poisoned the integrity” of the local artists and that Emma Lake “grew, achieved maturity, faltered and finally substituted for creative exploration an imported, critically secure painting theory.”

The writer Robert Enright noted in a 1984 issue of Canadian Art that “to understand how modernism established its grip—some would say stranglehold—on the collective imagination of Saskatoon’s artists, one has only to study the history of the Emma Lake Workshop.”

Imported or invited, stranglehold or inspiration, Greenberg’s visit still ripples. But I would argue that he was never more of an influence than the workshops themselves. The place, the sheer incredibleness of the location, and the workshops’ focus on process and dialogue and relationships—that is the primary influence on how art developed there through the century.

Artists need a place to explore and experiment, one that tests them in unexpected ways. Emma Lake provided that. Maybe the best example of this occurred in 1965, when one of the most influential process artists came all the way to Emma Lake only to embark upon a complete comedy of errors. Everything went wrong, and it was perfect.

The organizers decided to invite John Cage. His process often produces no clear product. He’s very relational. In 1952, he staged a nonconcert that some consider the first “happening,” a performance event where indeterminate elements just “happen.” His most famous piece of music is “4′33″,” four minutes and thirty-three seconds of a musician sitting at a piano playing nothing: silence. What did he accomplish as a mentor at Emma Lake?

Cage, whose transcendental experiences with nature often occurred when going off into the forests of New York with a wicker basket, collecting boletes and morels, apparently could not conceive of the scale of the wilderness around Emma and “got lost in the muskeg,” as Godwin put it, after he went out alone on just such a mushroom forage. “Yelling, startled moose,” Cage wrote of the experience. “8:00 darkness, soaked sneakers; settled for the night on squirrels’ midden. . . . Rationed cigarettes (one every three hours: they’d last ’till noon) Thought about direction (no stars).” He wandered until a search party found him the next day.

The disasters kept piling up. There was a forest fire nearby. McKay fell ill and had to hand over administration to another artist. Knowles got sick and left after a few days. And the cook was terrible and “up-tight.” Sculptor participant Ricardo Gómez described to King how “the atmosphere was tremendously electric. In a way, it was beautiful that it sort of culminated in that fantastic mind-snapping event where everything—it was just fantastic. Every conceivable thing that could possibly go haywire with anything, did.” Ironically, many who participated seemed to think the two weeks with Cage were inspiring, even if they appeared to have no immediate impact on the local psyche.

Chance, randomness, and uncertainty were all essential to Cage’s process. They also define the history and future of Emma Lake. After a few decades of sporadic programming, the Emma Lake Artists’ Workshops have been indefinitely closed since 2012, suffering from a lack of funding. There have been efforts to revive the program, though no resurrection has yet occurred.

According to Abstract Painting in Canada, Greenberg once said to Godwin: “The history of Canada is written in the landscape.” Greenberg was not wrong. But the history of the land is on another scale entirely and far more enduring than the history of a nation-state. And an artist is only ever beholden to the long history of the universe.

The only mandate Emma Lake ever required of its participants was time alone together in the sanctuary of this awe-inspiring landscape. They just needed to bring themselves fully. Six decades of the Emma Lake Artists’ Workshops granted Saskatchewan a dynamic, unpredictable relationship to contemporary art, and we are all worse off for their absence.