E

very novelist is an explorer without a map; a miner without a headlamp; a wordsmith capable of more expertly crafted metaphors than these. Yet for every considered paragraph, painstaking outline, and precise choice of font, there are a million ways for even the most nimble author to get lost in the plot. Luckily, as many will tell you, that’s where the literary richness tends to lie.This year’s nominees for the Amazon Canada First Novel Award weren’t shy about plumbing the depths of their respective family histories, of Canada’s history, the minds of their protagonists and, in one case, the underbelly of the country’s arts scene. They rifled through a heady combination of tangible documents and their own dreams and memories for material—some of them incredibly thorny, emotional and, until now, unspeakable. Then, they offered it all to readers. If fiction is, in many ways, the art of revelation, we wanted to know what they discovered while lurking around in the shadows, and what they found out about themselves in the process.

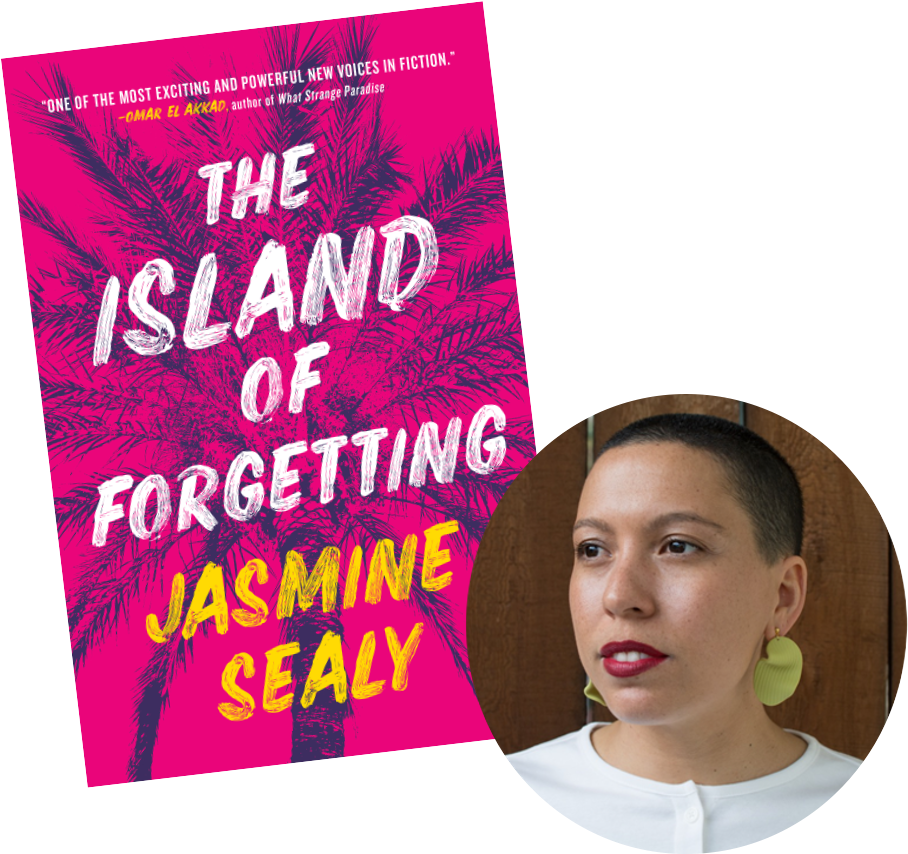

The Island of Forgetting is a novel about silences and secrets—about all the things that go unsaid in a family, particularly between generations. So, in many ways, writing it was about deciding what to keep hidden and what to reveal. I discovered that I loved playing with shadows, that the process of creating a character is as much about what I leave off the page as what I include. Writing this book also led me to interrogate my own self narratives more deeply, to question long-held beliefs and assumptions, and to understand that everyone has a story that is greater and more complex than you can ever truly know—even, perhaps especially, those closest to us.”

– Jasmine Sealy, The Island of Forgetting.

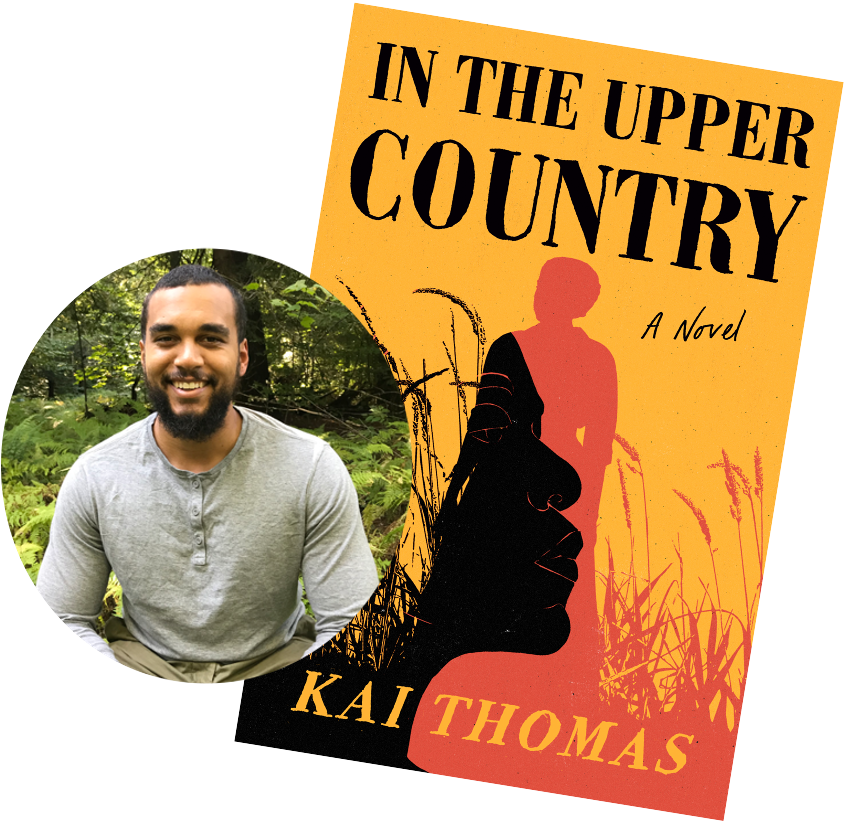

“Fiction is shadow work, isn’t it? On one level, words are the shadows of meaning, and as writers we deal in silhouettes—letters on the page. In another sense, in its substance, a good story is not contented with the portrayal of that which is obvious and already illuminated. We must go to the shadows. What did I find there? Many stories, fascinating and obscured by years of history and forgetting. They were stories of this land and its ecologies—and of Black and Indigenous life here—intersecting in ways I had never imagined. I found stories that gave radically new and interesting perspectives to historical moments, such as the Underground Railroad and the War of 1812. In myself, I discovered surprising connections to these stories through the themes of my own experiences, as well as my ancestry. I found, too, a profound desire to follow my own curiosity and sensibility, and to try, try, and try again to put the words down in the right way.”

– Kai Thomas, In the Upper Country

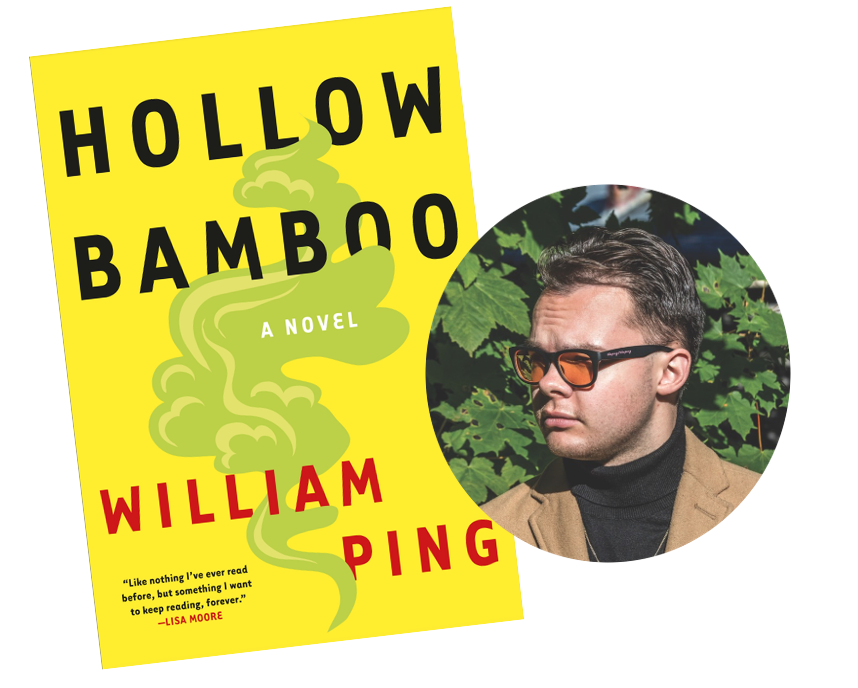

“In writing Hollow Bamboo, I found more information about my own family, but also more mystery. In writing the story of my grandfather’s life, I engaged in a lot of research: from historical documents and university studies, to collecting family anecdotes. A ‘list’ of facts and notable dates helped shape the arc of the novel, but it didn’t always tell me about how these events felt as they transpired. Sometimes imagination is necessary to access a truth beyond facts, and there is a lot of imagination in these pages. That being said, I do think I came to a better understanding of myself, my family, and my people. I think many readers feel that the deep-seated racism in Newfoundland depicted in the book is a revelation.However, I didn’t find that in the shadows. I knew racism was a problem, both yesterday and today. Sadly, it will still be a problem tomorrow. Part of the impetus behind the novel was bringing those issues to light in a context where a lot of people have deluded themselves into thinking: racism doesn’t exist here. Racism does exist in Newfoundland, just as it does across Canada.” – William Ping, Hollow Bamboo

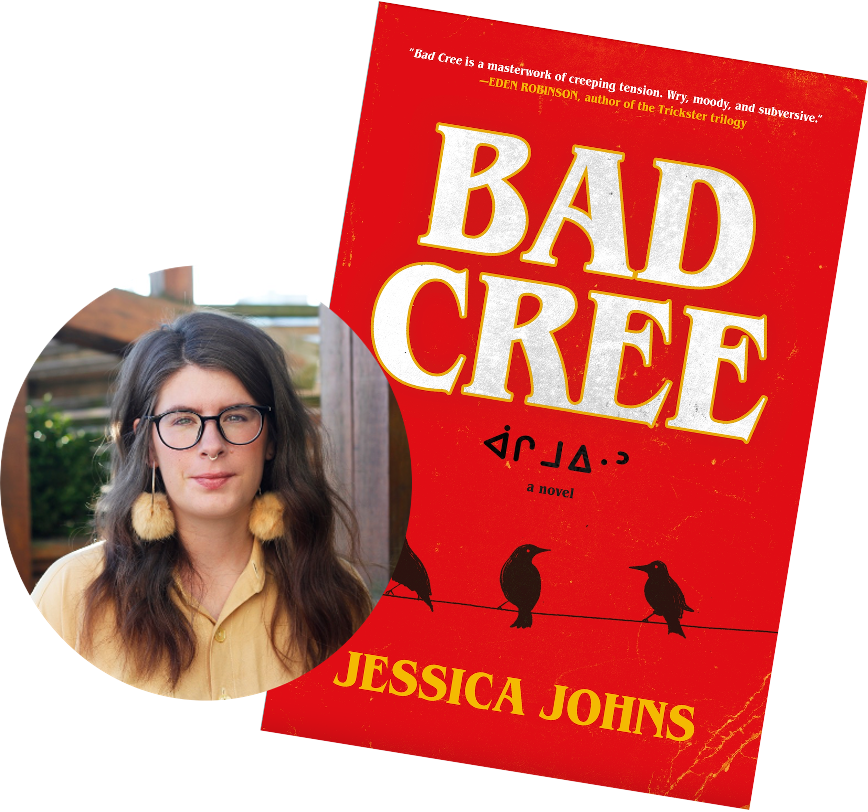

“Bad Cree explores the dark underbelly and the violence of the oil-field industry, particularly in Alberta. Communities in this area experience devastation of the land years after the industry takes hold of the place—a kind of violence that is very common within extractive industries. Marginalized communities are intimately aware of that, but I don’t see it talked about a lot in communities that are more privileged. They have distance.

I really wanted to write a novel that centered Indigenous women and queer Indigenous people, as well as the significance of dreaming for Cree people. What I didn’t know was that Bad Cree was going to be so heavily focused on grief and loss. The characters are all at different stages of it: the grief over their families, the grief over their land, the grief that comes with changing relationships. I think that Indigenous people are always collectively grieving. That experience is not foreign to me at all. I thought and learned a lot about what death means, culturally. I got to feel a lot more connected to what it means to our ancestors when they do pass. That was healing for me in a lot of ways.”

– Jessica Johns, Bad Cree

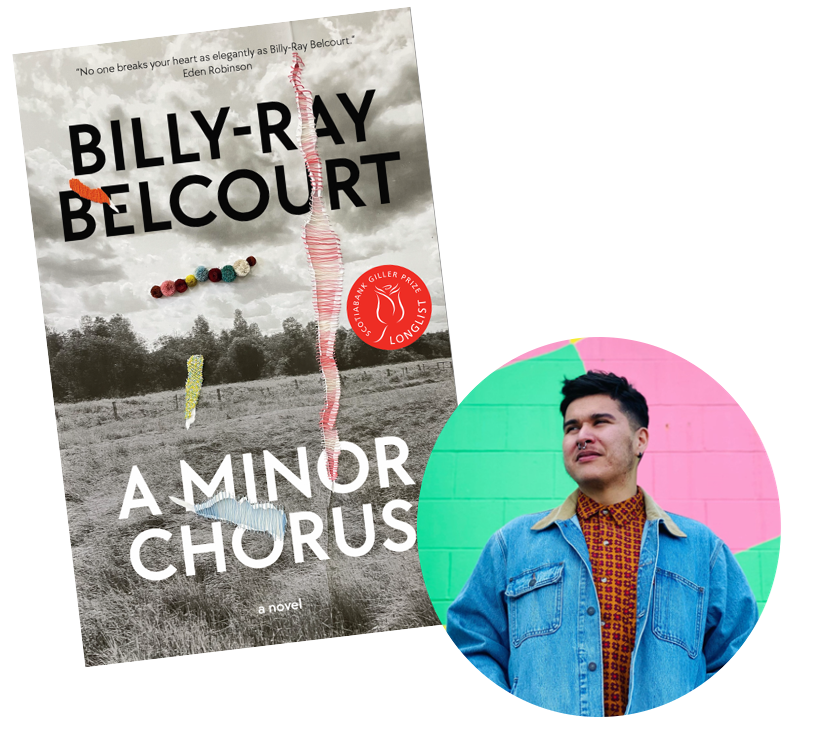

“‘The shadows’ evoked firstly for me the unconscious. So much of writing the novel involved writing into the unknown, into what didn’t immediately emerge as subject matter. I ended up landing on a narrative voice much like my own voice after a year of experimentation and false starts. The story I could tell was inside me all along—a story about rural Alberta and the afterlives of the long twentieth century. Herein lies another shadow: the deep shadow of history. I believe that the people most brutally affected by historical violence are rarely empowered to give expression to their experiences of that violence. I wanted the novel to illuminate the ways ordinary people, both Indigenous and non-Indigenous, make sense of their enmeshment in structures of oppression and, importantly, in practices of freedom. The present is made up of the past: it’s a simple statement with intensely material and emotional consequences. The form of the novel allowed me to explore terrains of experience that are outside my immediate vicinity; I could tell a larger story of how people desire flourishing and love against the grain of racism, misogyny, and homophobia.”

– Billy-Ray Belcourt, A Minor Chorus

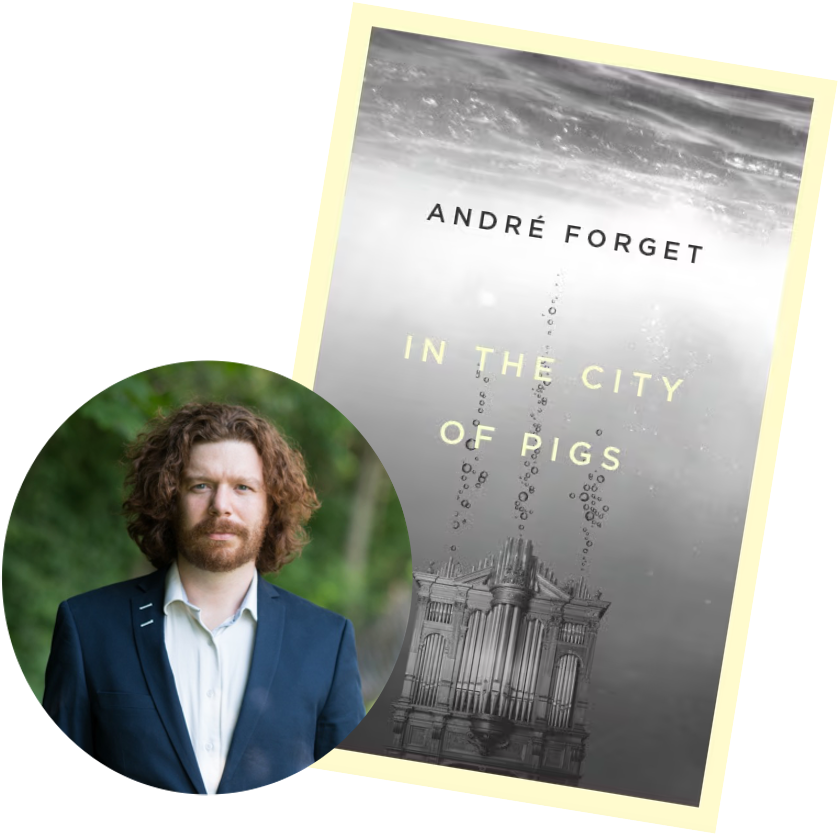

“When I started writing In the City of Pigs, I thought it was just going to be about music and the people who make and perform it. I did not realize I was also going to end up writing so much about development, modernity, capitalism, and Toronto. I suppose what I discovered was my own deep ambivalence about all these things. Toronto crept into my writing because I was living abroad and missing home. The more I wrote, the more I came to realize that I love the city the same way I love art—that is to say, with a mixture of exasperation and disgust. On the one hand, there’s the cosmopolitanism and liveliness, the subtlety and excess; on the other, the self-satisfaction, venality, priggishness, greed, and myopia. Perhaps this is one of the reasons I’m drawn to the novel as a literary form. It leaves you with a lot of room to be ambivalent, to look at something and say, ‘I can’t stand this, but I’d be heartbroken if it stopped existing.’”

– André Forget, In the City of Pigs