In January, the Alberta Party, a centrist provincial party, posted a video on its official Instagram account. The since deleted video, which is still available on their Twitter feed, was of a man in a blue sweater facing the camera, with the Calgary skyline behind him. But something about him was off. “Does Alberta need a third political party? It depends on whether or not you’re happy with your current choices,” the man stated flatly, before suggesting Albertans seek “another option” on election day. His mouth didn’t form vowels properly. His face was strangely unmoving. And then there was his voice—it didn’t sound fully human.

That’s because it wasn’t. The video was AI generated. In a since deleted post, the Alberta Party clarified that “the face is an AI, but the words were written by a real person.” It was an unsettling episode, not unlike one from the hit techno-dystopian series Black Mirror in which a blue animated bear, Waldo, voiced by a comedian, runs as an anti-establishment candidate in a UK by-election.

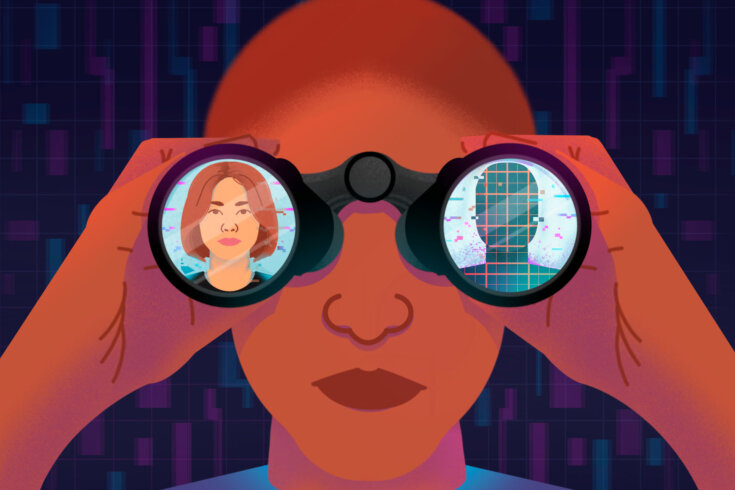

“ . . . wherever the people are well informed they can be trusted with their own government,” Thomas Jefferson wrote in the winter of 1789. In other words, in a democracy, being informed grants people agency, and having agency gives us a voice. AI has the potential to challenge both of these critical assumptions embedded for hundreds of years at the heart of our understanding of democracy. What happens when the loudest, or most influential, voice in politics is one created by a computer? And what happens when that computer-made voice also looks and sounds like a human? If we’re lucky, AI-generated or AI-manipulated audio and video will cause only brief moments of isolated confusion in our political sphere. If we’re not, there’s a risk it could upend politics—and society—permanently.

Much of our fate hinges on our familiarity with what we’re seeing. Take bots, for instance. These automated or semi-automated programs are powered by AI, and social media platforms are already replete with them. They are commonly used to fake follower counts, auto-respond to customer queries, and provide breaking news updates. More concerningly, they’re also used in campaigns to either influence public debate or, in some cases, harass people. But these kinds of bots remain text based. What the Alberta Party created, and what others are making, is much different. It challenges what we see and hear.

In 2018, actor and director Jordan Peele allowed his voice to be digitally altered and then grafted onto a manipulated video of Barack Obama so that it looked like the former US president was actually speaking Peele’s script. This kind of video is made with generative AI and is called a “deepfake.” Peele’s was created as a warning against the potential for sophisticated misinformation campaigns in the future, including the 2020 US election. But that election passed without any significant AI-induced confusion. Instead, “simple deceptions like selective editing or outright lies have worked just fine,” NPR concluded that year in an attempt to explain the lack of deepfakes.

But, at the time, there were technical and cost limitations. “It’s not like you can just download one app and . . . provide something like a script and create a deepfake format and make [an individual] say this,” one expert told the broadcaster. “Perhaps we will [get to that point] over the next few years, then it’s going to be very easy, potentially, to create compelling manipulations.”

We’re there now.

In February, an Instagram account posted a video purportedly of President Joe Biden making offensive remarks about transgender women. The audio had been generated using an AI program that mimics real voices. It was flagged on social media as an “altered video,” but it gained traction and was reposted by some right-wing American media outlets. Even Biden’s supporters have taken to doctoring his voice. “I ran into a very important friend over the weekend,” Pod Save America co-host Tommy Vietor, a White House staffer during the Obama administration, said in a recent episode, before playing a clip of what sounded like Biden. Vietor quickly admitted he’d paid $5 at elevenlabs.com to make the clip.

There’s an important difference between what the Alberta Party posted—a person created entirely by a computer—and the synthesized audio-visual representation of a real human, like the sitting president, in a deepfake. Still, the reaction to each is similar: people get confused. One reason for that is unfamiliarity. “One of the key things is . . . digital literacy from a public perspective,” says Elizabeth Dubois, university research chair in politics, communication, and technology and associate professor at the University of Ottawa. “As these innovations become more embedded in campaigns . . . people will generally become literate about what’s happening and how things are showing up on their screen. But in these early stages where this experimentation is happening, that’s when we see the most chance for people to just not really understand what’s going on.”

But the media under manipulation is also important. By doctoring video and audio, these videos upend social expectations about the relationship both have with objective truth, says Regina Rini, Canada research chair in social reasoning at York University. Technically, bots say things verbally—or using text. And while we generally have an innate understanding that verbal or written statements can be untrue or mistaken or deceptive, Rini says, we’re less inclined to be as skeptical in case of audio-visual media. “Everyone knows it’s possible to fake traditional photos. . . . We’ve known it’s possible to tinker with videos,” says Rini. “But the degree of . . . default skepticism has been a lot lower for audio and video recordings.” Generative AI is changing that.

It’s possible that the gradual introduction of AI-manipulated video and audio in everyday discourse will acclimatize the general public to it in the same way that we became accustomed to text-based bots. On the other hand, all hell could break loose if a large number of people are required to assess the authenticity of a video or audio clip before we’re ready. A nightmare scenario, says Rini by way of an example, is if a deceptive video with significant geopolitical implications were to go viral, such as a fake conversation between Joe Biden and Vladimir Putin—“you know, the kind of thing that can start wars.” But even a slow drip could erode the foundation of our shared reality. “The thing that scares me is that we don’t fall for them, or most of us don’t fall for them, but they just continuously pop up one by one over time. And we’re constantly fighting over whether or not we believe in the latest instance of media,” Rini says. “That cumulative effect over time of lots of little instances of that, and some big ones too, eventually to build up to the point where we stop trusting media in general.”

If you think this is far-fetched, consider an example from just outside the political realm. In March, a video clip from something called the Caba Baba Rave circulated on Twitter, amplified by right-wing accounts like Libs of TikTok. Caba Baba Rave is a UK-based drag cabaret. The viral video showed an event where drag and non-binary performers put on a show for parents of very young children. Caba Baba Rave called it “a cabaret show designed for parents, with sensory moments for babies.” The clip caused an uproar, not just because of its content but also claims that the video was doctored. Soon enough, an entire sub-discourse erupted about whether someone had doctored the video to make an ideological point. But the video was real, as Caba Baba Rave confirmed. In spite of that, some users still didn’t believe it was.

Even when social media users aren’t convinced videos are deepfakes or otherwise doctored, the levels of scrutiny currently devoted to just the most benign clips, particularly on TikTok, suggest an insatiable appetite for debate over the veracity of video and audio. In other words, the internet has been primed for exactly the kind of fight Rini warns against—an endless war of meta skepticism.

There’s another, less public way that we may reach a point where the framework of reality starts to bend beyond our understanding. While AI changes the terms of the public debate online, it will be deployed in ways that are less visible too.

It’s already possible for avenues of public consultation, including social media, to be flooded with bot-generated messages, but AI offers potentially more effective, not to mention vexing, scenarios. Here’s one outlined in research released in February from Nathan E. Sanders, a data scientist at the Berkman Klein Center at Harvard University, and Bruce Schneier, a security technologist at the Harvard Kennedy School. A political actor (let’s say a lobbying firm with deep pockets) creates a machine-learning program designed to graph a network of legislators based on their position, seniority, level, past voting trend, statements, or a multitude of other factors, allowing the firm to concentrate their lobbying efforts on those politicians predicted to have the most influence on a given legislative strategy.

The kind of tool Vietor showcased on the podcast introduces an even more bizarre possibility. Maybe you wrap that predictive machine-learning model into a system that has the ability to phone a politician’s office and carry out a conversation about that legislation using an automated, synthesized voice. And maybe that voice sounds a lot like one of their constituents. Or the prime minister’s.

“How do you prevent that from biasing, distorting our political process?” Sanders asked during our conversation. “Our fundamental recommendation in that regime is to make it easier for people to participate. . . . Make it easier for real people to have their voice heard as well.” Sanders pointed out that some AI tools are already doing that, including ones like Google Translate, which make it simpler for some people to get in touch with their representative by translating messages from their language to their representative’s language.

To be clear, technology is no stranger to politics. “We should expect that, with any new technologies, people are going to try and figure out whether or not there’s a way to make politics better, more effective, cheaper,” says Dubois. Sanders echoes this, pointing to existing tools like mail merge, a method for sending personalized messages in bulk, that political parties and candidates have used for many years. “I don’t think it’s really that different from using the AI tool to take, you know, three or four facts about you and then trying to generate a more personalized message.”

In Canada, rules dictating AI use during a political campaign aren’t specifically articulated in the Elections Act. But Elections Canada does have rules against impersonation or false representation with the intent to mislead. “Misleading publications” are also prohibited—that’s “any material, regardless of its form” that purports to be from the chief electoral officer, returning officer, or political candidate. Other than in instances that might relate to impersonation or misleading publication, Elections Canada does not “actively look for deepfakes, fake images and videos,” the agency said in an email.

But Elections Canada is only concerned with election periods. Government legislation would cover everything else. However, the use of AI for political purposes doesn’t appear to be mentioned in Canada’s new AI law that is moving through Parliament, and an email to the office of the minister for innovation, science, and industry, seeking clarification, went unanswered.

For Mark Coeckelbergh, professor of the philosophy of media and technology at the University of Vienna, AI may help push typical persuasion into more negative territory. Politicians naturally try to influence us, he says, but “the problem with many of these technologies is that they enable the more manipulative side rather than persuasion by argument and information,” he says. “What you’re doing is you’re treating people not as autonomous, enlightened kind of subjects . . . you’re treating them like lab rats or any kind of thing you can take data [from] and you can manipulate.”

How far could that manipulation really go? Politicians and political candidates are already capable of lying to voters. In one recent high-profile case, Republican George Santos admitted that his résumé, on the basis of which he campaigned for—and won—a seat in the US House of Representatives, was filled with fabrications, including about his education and work experience. If a real-life human can deceive voters so easily, could a fabricated one do the same?

Last year, the Synthetic Party, a Danish party founded by an artist collective and tech organization, drew attention for trying to run candidates led by an AI chat bot named Leader Lars. To run an actual AI-generated candidate in a riding in Canada would likely require some level of fraud. However, the toughest barriers to navigate—identification (the list of acceptable documents is long and not all require a photo) and the recommended 150 signatures from riding residents—are not insurmountable. Campaigning would be via social media. Debates could be ignored, as they sometimes are by real candidates. Under these circumstances, could an AI-generated candidate convince people to vote for it without them realizing it was fake?

Sanders doesn’t think a full AI candidate would pass muster. “I think, in general, it won’t be possible,” he says, noting that we as a society would be able to catch something like this before it happens. Dubois suggests what she sees as a more likely scenario: parody content, like the fake clip of Joe Biden, gets mistaken for communication from a real candidate. “We know that when people are scrolling quickly, they sometimes get confused, they don’t notice the label, they think it’s really funny, so they’re going to share it anyway,” she says. “And then, because they shared it, they are a trusted source to someone else, and then somebody else sees it. So you could imagine that sort of knock-on effect.”

“I think someone will try it, perhaps as a stunt,” says Rini, adding that its success might be geography dependent, like in a rural area where voters might be less likely to attend in-person events. Or it might just be about finding the right opportunity and party. “If you targeted an extremely uncompetitive house seat in the United States . . . and for whatever reason the primary wasn’t closely contested, [it] might not be hard to pull this off.” Canada’s bilingual political scene may offer a different kind of opportunity—not to fabricate a candidate but rather language, with a deepfake that makes an anglophone candidate fluent in French. For his part, Coeckelbergh is more certain about the possibility of an AI-generated candidate. “Absolutely. It’s going to happen.”

In fact, one might not even need to hide it. About two-thirds of the way through Black Mirror’s “The Waldo Moment,” a TV executive, Jack, argues with the cartoon bear’s human creator and voice, Jamie, about Waldo’s legitimacy as a candidate. “Waldo’s not real!” Jamie says. “Exactly . . . He’s not real, but he’s realer than all the others,” Jack replies. “He doesn’t stand for anything,” Jamie says. “Well, at least he doesn’t pretend to!” says Jack.

There’s a chance we’ll all end up siding with Jack, no longer debating about our political beliefs but whether we can believe—let alone believe in—anything at all. There’s also a chance we might prefer this debate to one about reality. We may find it more engaging anyway.