“I just saw a UFO,” he said.

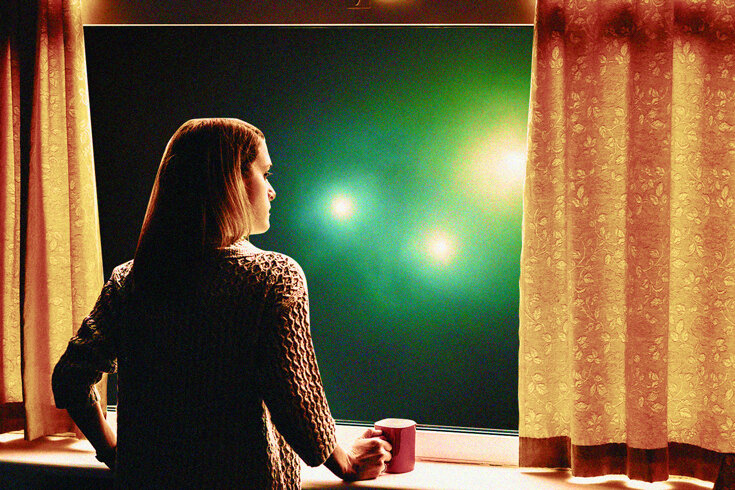

When my brother phoned at eleven one night, I panicked. Nick usually gives me a courtesy text before calling, so my mind went into crisis mode as I picked up the phone. I thought of potential family deaths or the kind of trauma he might come to me about first. I had visions of the night he walked away from a car crash, the only one of his group of four friends still conscious, our mom’s purple Acura a pile of twisted metal. I answered, bracing for the worst. But this felt like a prank. UFOs were the stuff of fantasy.

“Are you on anything?” I asked.

“I’m sober.”

Even as he meticulously explained the encounter, I couldn’t bring myself to accept his testimony. House-sitting for our parents, Nick had been looking out on the backyard under an April night sky when three bright lights, moving at a steady high speed, converged above the in-ground pool. They stopped, according to him, snapping into place and hovering in a triangle formation before beginning to rotate. The triangle’s spinning accelerated, it got smaller, and it vanished.

“I got a video of it,” he said, as if my disbelief radiated over the line. “Near the end. I didn’t record it all since I dropped my phone.”

He hung up and sent me a video over email. Sure enough, two static lights in the sky above our parents’ pool were joined by a third, moving in a direct line at a speed that reminded me of a marble rolling down a slightly uneven table and stopping on a divot. They revolved on an invisible axis, just like Nick said, and disappeared.

I played it over and over, a cold dread crawling up my spine, my muscles tensed ever so slightly in apprehension. My brain started doing gymnastics, trying to fit the image into a rational narrative. Consumer-grade drone technology wouldn’t be available for years, so my knee-jerk reaction was to believe it was a military aircraft. Already, I was in dangerous territory, the stuff of conspiracy theory, but any alternative explanations that came to mind were even more clichéd, if not any less likely to be true. Aliens. Robots. Atlanteans.

I had to admit I didn’t actually know enough about statistics to confidently say a secret government aircraft was any less probable than extraterrestrial visitation or the existence of a technologically sophisticated submarine species that lives in a sunken city that has somehow evaded human detection. If this was real, whatever real meant in that moment, then it would change everything. After all, the existence of UFOs should unite feuding nations in shared curiosity and fear, like in the ending of Alan Moore’s Watchmen, when a staged alien attack defuses Cold War tensions. Intelligent engineering of unknown origin is up there with climate change and pandemics on the list of big deals for the human race.

The next morning, at my customer-service call-centre job, I read the news in between answering phones. Apparently, there had been multiple UFO sightings the night before, all over southern Ontario. But reading about the encounters in print made the proposal of flying saucers difficult to square with my fluorescent nine-to-five present, working for an hourly wage in business-casual dress, selling tickets to the symphony. When I talked about Nick’s video with my coworkers at the coffee machine, needing to share my personal connection to the news du jour, I steeped my story in cynical disbelief. Only crazy people believe in UFOs, even when there’s video evidence. Especially when there are videos. The incident felt notable and dramatic, but I wasn’t ready, emotionally, to accept The X-Files as nonfiction.

Aired from 1993 through 2002, The X-Files was among the most popular American television dramas of its decade. Following the investigations of Fox Mulder and Dana Scully, two outcast FBI agents working out of the bureau’s basement office, the show was a paranormal procedural that borrowed heavily from real supernatural lore to bring a sense of uncanny verisimilitude to its episodic format. Encountering vampires, haunted dolls, the Jersey Devil, and a time warp in the Bermuda Triangle, Mulder and Scully peppered their mystery-solving banter with spooky factoids and trivia along with a helping of fringe science that made even their goofier adventures seem just a little bit plausible. While the agents investigated every possible horror trope, sometimes twice (Scully fought off multiple Mulder doppelgängers in the nineties), they are best known as heroes tangled in an ongoing government conspiracy to prepare Earth for colonization by alien visitors.

Roughly six to eight hours of every twenty-something-episode season were dedicated to a semiserialized plot drawing from real military history and actual abduction accounts. These episodes built the popular mythology of UFOs, aliens, and evil men who smoke cigarettes in gloomy Pentagon offices while watching presidents die. The mythology is so dense, so popular, and so blended with reality that it became the main cultural touch point for UFO phenomena. Fiction co-opted the less-verifiable eyewitness parts of reality to build a realistic mythos, which became the foundation for how we understand unidentified flying objects: as fantasy rather than as an area of inquiry worth investigating. Mulder and Scully were science-fiction all-stars worth emulating only in allegory.

In a May 2000 LA Times cover story titled “Hangin’ Out with Rock’s Rude Boys,” staff writer Geoff Boucher chronicles a day spent with Blink-182 when the band was scheduled to appear on The Tonight Show with Jay Leno. A case of laryngitis contracted by the band’s co-frontman and bassist, Mark Hoppus, meant a last-minute set change that replaced the ultrapopular suicide ballad “Adam’s Song” with “Aliens Exist,” a Tom DeLonge–sung tune. “It’s about aliens that come down to Earth and fly up your butt,” DeLonge told the LA Times. “And it’s true.”

Despite DeLonge’s in-your-face allegation of extraterrestrial probing, “Aliens Exist” is played deadpan on Blink-182’s 1999 pop-punk landmark Enema of the State. The guitarist recites, “We all know conspiracies are dumb,” but that doesn’t stop him from abandoning the tongue-in-cheek, running-naked-through-the-street aesthetic that made his band famous. The song sounds like the frustrated confession of an obsessed young man, with nary a Uranus joke.

Fifteen years after the Tonight Show set, DeLonge’s earnestness on the topic became clear when he quit the band and began pursuing ufology, writing books about alien technology and exchanging emails with US government officials like John Podesta on topics such as Area 51 and the infamous Roswell incident. DeLonge even launched a company called To the Stars Academy of Arts & Science, a startup dedicated to harvesting and learning from UFO technology with the aim of sparking revolutions in science, engineering, entertainment, and consciousness. (While no mention of ESP research remains on the To the Stars website as of this writing, a 2017 preliminary-offering circular archived with the US Securities and Exchange Commission references the company’s research into telepathy.)

DeLonge came across as ridiculous because he was acting like a character from The X-Files. He might as well have joined the Church of Scientology, come out as a flat-earther, or asserted that he could speak with animals like Doctor Dolittle. Of all the things a person could possibly dedicate their life to, UFO research is among the most lethal to one’s public image.

But DeLonge and other ufologists and alleged abductees should have been exonerated on December 16, 2017, when the cover story of the New York Times Sunday edition exposed a clandestine Department of Defense program dedicated to the study of unidentified flying objects. The Advanced Aerospace Threat Identification Program (AATIP) was started in 2007 by Democratic senator Harry Reid. Fuelled by $22 million of untraceable funding, the initiative investigated strange aerial phenomena that demonstrated motion capabilities far beyond the limits of human engineering and interfered with military weapons systems. Luis Elizondo, who ran the program from the Pentagon, characterized the objects as threats to national security that warranted serious research and analysis.

Despite documented video evidence of silvery shapes in the sky moving at impossible speeds and pivoting with grace, military personnel rarely reported close encounters for fear of ridicule. Such stigma seems to be the root cause of the program’s 2012 decommissioning. According to the New York Times’ sources, Department of Defense officials still independently investigate UFO reports, but they do so without departmental financial support. Frustrated with the continued secrecy, the defunding, and the overall lack of seriousness afforded a topic he still sees as high priority, Elizondo resigned from his government position to enter the private sector. He and two other former Pentagon officials now seek the truth alongside DeLonge at To the Stars Academy, corroborating the paranoid punk rocker’s radical and fantastical world view.

UFOs are real in the most clichéd sense, which makes them nearly impossible to believe in if you didn’t already entertain their existence before 2017. In borrowing from the highly stigmatized UFO-sighting subculture, The X-Files made us associate legitimate unknown phenomena with a very good but also extremely silly television drama. Now that AATIP has been dragged into the light of day, the UFO episodes of Mulder and Scully’s adventures almost play like historical fiction rather than sci-fi. Almost. Because the U in UFO is a scary U. The unidentified. The unknown. The unclassifiable.

By the end of its initial, nine-season run, The X-Files provided answers to all of its alien mysteries. In real life, Elizondo and DeLonge don’t have those answers. No one does. The narrative is unfinished, and it will remain that way if we can’t accept that the pariahs weren’t lying when they told us about the shining lights in the sky.

It’s ironic that The X-Files’ accuracy makes it so difficult to believe the assertions of UFO spotters. Not only did the show endeavour to portray abductees and witnesses in a sympathetic light—often to tear-jerking effect, as in the case of recurring character Max Fenig, who endures a lifetime of torture made all the worse by society’s unwillingness to accept his story—but, in the show’s finest hour, season three’s “Jose Chung’s ‘From Outer Space,’” Mulder shares a powerful monologue about the influence of popular culture on highly stigmatized communities. Urging author Jose Chung to abandon the writing of a nonfiction book about the alleged abduction of two teenagers by a lava monster named Lord Kinbote, who hails from the inner space of Earth’s core, Mulder says:

You perform a disservice to a field of inquiry that has always struggled for respectability. You’re a gifted writer, but no amount of talent could describe the events that occurred in any realistic vein because they deal with alternative realities that we have yet to comprehend, and when presented in the wrong way, in the wrong context, the incidents and the people involved in them can appear foolish, if not downright psychotic.

In the world of the show, Mulder is the voice of compassion. But, to a viewer, every episode of The X-Files functions like Chung’s book. Even when it’s serious, the show is still fantasy—created, presented, and consumed in a reality that largely dismisses the nonreligious paranormal. The X-Files uses its UFO mythos to teach us about faith, skepticism, human connection, and trust. But its most straightforward lesson, that we should take UFO sightings seriously, falls victim to our deeply ingrained reading habits regarding genre fiction. We dismiss it as an entertaining vehicle for a deeper meaning. Sci-fi isn’t supposed to be literal.

Even writing this, I feel torn between what I know from the news and my expectations of reality. I’ve seen video evidence of a UFO. I’ve read the New York Times exposé and subsequent reports. On their own, they should provide me with enough of an informed vantage point to accept our strange new skies. But, for some reason, I can’t fully accept this as one of Mulder’s “alternative realities.”

The truth is out there, and I’m filled with a DeLongean frustration that society is more concerned with the explainable earthbound threats facing the Pentagon and the increasingly rigid lines of partisan human-on-human conflict. We should be trying to figure out this UFO thing. We should be dedicating all of our time to searching for answers to skyborne unknowns. We should unite as a species out of shared curiosity and, possibly (if Elizondo is right about UFOs being a threat), self-preservation. I should quit my job and join To the Stars—but I can’t bring myself to put my money where my mouth is.

Fifty-one percent of my mind thinks buying stock in DeLonge’s firm would be a very funny joke but ultimately not worth the $350-minimum price tag—despite the US military’s continual validation of DeLonge’s views. Cynicism informed by pop culture always conquers fear. My paradigm is jammed by The X-Files. I want to believe, but I can’t.

Excerpted with permission from Be Scared of Everything: Horror Essays by Peter Counter (Invisible Publishing, 2021).