Listen to an audio version of this story

For more audio from The Walrus, subscribe to AMI-audio podcasts on iTunes.

A white shark is human fear made flesh. It shears the water like a missile targeting its prey, with conveyor-belt rows of serrated teeth and skin so rough it was once used as sandpaper. From a primordial perspective, our fear of these creatures is understandable. But we’re a peculiar species, fascinated by what terrifies us. From Jaws to Shark Week to any news about the long-extinct megalodon, sharks occupy an intersection between terror and entrancement. So when one starts tweeting, of course we follow.

In March 2017, an American research group called Ocearch caught a 600-kilogram, 3.7-metre-long white shark off Hilton Head Island, South Carolina, bolted a flashlight-sized satellite transmitter to his dorsal fin, and named him Hilton. Thanks to Ocearch’s Global Shark Tracker app, researchers and even amateur shark enthusiasts could watch Hilton’s migration as he stormed up and down the eastern seaboard.

Ocearch gives many of its transmitter-tagged sharks Twitter accounts run by a team of staff, volunteers, and scientists. As a part of its program to connect more people with ocean life, it’s working: with nearly 50,000 followers, Hilton (along with @MaryLeeShark and @RockStarLydia), is a minor celebrity. To counter the popular depictions of bloodthirsty predators, Ocearch presents @HiltonTheShark as just a jaunty guy on the hunt for food and love. On January 20, for instance, along with a GIF of a white shark leaping out of the water, his account tweeted: “Doin’ my happy dance here off the coast of Georgia . . . dance with me everybody!” A few months after Ocearch caught him in 2017, Hilton was swimming (and tweeting) along Nova Scotia’s Atlantic coast, and that summer, he became the province’s unofficial mascot.

Thanks partly to this marketing initiative, Ocearch—a scientific non-profit that grew out of a reality-television show—has become one of the best-known, and most controversial, ocean research outfits in the world. At the organization’s helm is Chris Fischer, an academic outsider trained in international sales rather than biology, who views science much like a tech entrepreneur sees any tired industry in need of an overhaul. Traditional academic research has followed a strict process for centuries (research, peer review, publish), through which scientists’ publications become locked in intellectual property. But, in a time when environmental catastrophe follows us like a shadow, Fischer believes it’s now more important than ever that data belongs to and is accessible to everyone—which is why he is unafraid to burn bridges with those who object to his move-fast-and-break-things approach.

Fischer often invokes Jacques Cousteau, the beloved filmmaker, television host, and ocean adventurer who died in 1997, as the inspiration for Ocearch. But, with a start-up founder’s obsession with disruption and growth, Fischer is more like the Elon Musk or Mark Zuckerberg of marine conservation. He even talks with Silicon Valley–esque hubris: “You choose to be an open-sourcing collaborator and explode your science beyond where you’d ever taken it before or to be an institutionally, individually oriented data hoarder and fall behind.”

Ocearch’s attempts to disrupt traditional science is bringing it global attention, but the organization is also at the heart of a bitter fight over truth and influence in the world of ocean science. For years, Ocearch has been accused of running roughshod over the communities where it operates and leaving a trail of bad blood between itself, scientists, and the public, from California to South Africa to Nova Scotia. Fischer appears to brush it all off. For him, the stakes are too high, and he’ll accept nothing short of a scientific revolution. And he may not be wrong—at least, not entirely.

Sitting back on a plastic deck chair aboard the MV Ocearch, the organization’s thirty-eight-metre Bering sea crabber turned shark-research vessel, Fischer doesn’t look anything like his idol Jacques Cousteau. Instead of a French accent, he speaks with a light Kentucky drawl. Where Cousteau was idiosyncratic, in his signature red toque, Fischer often wears a hoodie and ball cap emblazoned with the logos of corporate sponsors. But, like Cousteau, he is charismatic and a natural on camera.

As a kid, he caught fish and frogs in his hometown of Louisville, Kentucky, and spent hours watching Cousteau on television. But he didn’t follow that fascination into a career in science. Instead, he graduated from Indiana University with a business degree and started working in sales for SerVend, a beverage-machine company founded by his father and older brothers.

Fischer was twenty-nine and living in California, commuting to and from countries across Asia for work, when his family sold SerVend in 1997. He decided then that he had a choice: keep selling pop machines or start a new life. Five years later, he was the star of ESPN 2’s Offshore Adventures, a fishing show he says he pitched and funded on his own. He met conservationists through his show, and in 2005, he started bringing biologists on trips to help them catch fish for research. Those scientists, Fischer says, told him how ocean ecosystems could hinge on apex predators, such as white and tiger sharks, which were in trouble due to finning and overfishing. Lose these balance keepers, they claimed, and the ecological webs around them collapse. “Going out and making a fishing show seemed like a really silly thing to do,” he says. “If I wanted to create balance in the ocean, I could be her servant my whole life.”

So he pivoted again, this time turning his ship into a floating lab that he renamed the MV Ocearch—a portmanteau of “ocean” and “research”—his own version of Cousteau’s retrofitted military ship, Calypso. The boat became the base to film his shark-focused docuseries-meets-reality-television show (first called Expedition Great White, then Shark Men, then Shark Wranglers), which premiered on National Geographic in 2010 and chronicled Ocearch’s research expeditions. “I was just young enough and dumb enough at the time that I just set a noble goal to pour the world’s oceans into people’s lives on a scale not seen since Cousteau,” he says, rattling off one of the quotable sound bites he often repeats in interviews.

Fischer is trained as a salesman, after all, not as a scientist—following in the wake of an idol whose methods have been criticized: in the 1950s, Cousteau used dynamite to blow up sections of the ocean floor to study what was living there. Fischer’s critics tend to be researchers who see him as a renegade operating outside the bounds of a tradition that has been fine-tuned over centuries. But, to Fischer, that tradition is no longer serving the needs of a planet suffering from climate change, ocean acidification, and the decimation of wildlife populations. Scientists have been analyzing white-shark populations since the 1970s in the northwest Atlantic Ocean, counting animals snagged as bycatch on longlines offshore and extrapolating those numbers to estimate population size. But this method is imperfect, and it doesn’t account for sharks that stay closer to the coasts. Reliable population numbers for white sharks in this region are non-existent. That’s part of the reason Ocearch and other researchers are tagging: they’re trying to solve a mystery and find out not just how many white sharks there are but where they’re going and breeding. “We need to find the data and manage them,” says Fischer. “If we don’t get the big shark thing right, our kids aren’t going to eat fish.”

But Ocearch may have other reasons for focusing on the conservation of white sharks, as opposed to, say, angel sharks, which are much more at risk but less iconic. According to Bob Hueter, Ocearch’s chief science adviser and a veteran shark biologist from Florida’s Mote Marine Laboratory, “I would be disingenuous if I didn’t say that the selection of white sharks is also based on the public’s reaction to that species.”

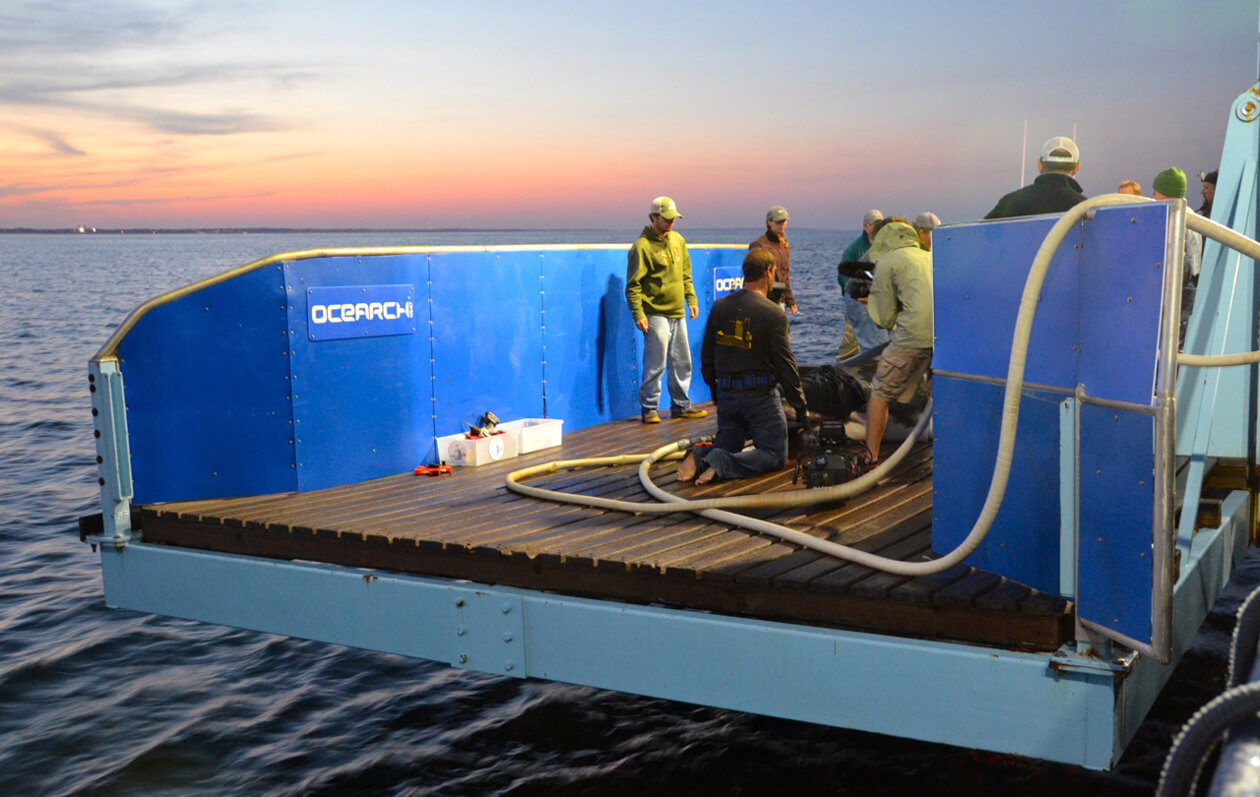

Ocearch’s tagging methods are unconventional, but that’s exactly why fans tuned in week after week to watch Fischer catch sharks on TV. While many researchers embed pop-up satellite (PSAT) and acoustic tags under a shark’s skin with a harpoon while it’s swimming or while it’s restrained along the side of a boat, Ocearch instead hooks the shark and lures it over to the ship and onto a specialized hydraulic lift. With the shark in position, the lift is raised out of the water, and a swarm of crew members and scientists rushes the deck, covers the shark’s eyes with a wet towel, and shoves a hose in its mouth to keep water flowing through its gills so it can breathe. They give themselves fifteen minutes to take samples, including blood, parasite, and muscle (plus semen if it’s male, and they perform an ultrasound if it’s female). And in addition to the other two tags, they bolt a smart-position and temperature-transmitting (SPOT) tag to its dorsal fin. By the time the shark is lowered back into the water, it has three tags pinging data to Ocearch’s app—and, soon after, a Twitter account. As Fischer says, they’re maximizing data from every shark they touch.

But lifting a 500-plus kilogram predator out of the ocean is inevitably a frenzied scene, and things didn’t always go smoothly in the beginning. Shark Men featured Fischer, his crew (including his long-time captain and collaborator Brett McBride), and shark biologist Michael Domeier, who came up with the idea of taking sharks out of the water for SPOT tagging in the first place. More Deadliest Catch than The Undersea World of Jacques Cousteau, the series seemed to exaggerate petty conflicts and dramatized the danger of working with white sharks. In the first episode of the second season, the crew accidentally gut hooks a shark while tagging near the Farallon Islands off San Francisco. McBride has to reach into the shark’s throat backwards through its gills just to cut the largest part of the hook out—all while the shark lies on Ocearch’s tagging platform, out of the water. But part of the hook remains lodged in place, and after the shark swims off, a local marine sanctuary suspends Ocearch’s tagging permit until the organization alters its techniques—all while cameras are rolling. Later in the episode, a stressed Domeier tells Fischer his professional reputation is on the line. Domeier was using unorthodox tagging and sampling methods and had potentially injured an animal he was studying. “My name is on all these permits,” Domeier says. “You guys can go home and make a fishing show—I’m stuck with this mess.”

“Yeah, my name’s on the permit too,” Fischer responds, arms crossed, looking exasperated.

“No, your career’s not at stake, Chris,” Domeier says. “Mine is.”

Domeier was called out for using such invasive tagging methods, and Fischer earned a reputation as a maverick. The pair’s relationship eventually disintegrated when Fischer says Domeier refused to give Ocearch part ownership of tagging data. Domeier declined to be interviewed for this story (“I have put my unpleasant experience with Ocearch behind me and would prefer to simply leave it there”), but in 2015, he told Outside magazine: “Scientists work in a world where we are measured by the value of our intellectual property. . . . Fischer latched onto one of my ideas, and it has done well for him.”

Since the Farallon incident, Ocearch has stirred up controversy almost everywhere it has gone. It has been criticized for chumming—dumping large amounts of fish guts and blood into the ocean as an attractant—in South Africa, where the group was blamed when a bodyboarder was killed by a shark near Cape Town (even though the city stated there was no evidence Ocearch’s chumming actually caused the attack). And, in 2016, after it was denied a permit in Massachusetts state waters, it started chumming and tagging in federal waters near the border of an area studied by Greg Skomal, a state biologist and a former Ocearch science partner. Skomal is adamant that Ocearch’s chumming changed the behaviour of sharks in the area. And while the government of Western Australia turned down the organization’s offers to help with local white-shark projects, inferring Ocearch’s tagging practices could place unnecessary stress on the animals, Western Australia Today reported that the state government was accused of “using information from the monitoring network to target great white sharks as part of catch and kill orders.” Fischer is quoted saying it would be “concerning” if Ocearch’s data were used.

In 2012, Ocearch’s reality show was cancelled, but Fischer concedes this was for the best. Ocearch was on a “path to abundance,” he says, which starts with on-the-water research and ends with changes in policy. “You can’t get meetings with policy makers and presidents if you’re the wacky guy on TV on Tuesday nights,” Fischer says. But getting off television also put his organization in a precarious financial situation, so he started selling and landing sponsorships in exchange for “brand-integrated content.” In effect, Ocearch became a conservation group with an advertising arm.

Today, MV Ocearch is plastered with decals of corporate sponsors, including outdoor-recreation-gear brands. Fischer has figured out a way to turn corporate money into funding for both scientific research and online entertainment for millions of people. Where, traditionally, biologists have tended to focus on populations over individuals, Ocearch knows that popularizing a single shark like Hilton means an audience is more likely to care about the larger issue. While these models may raise ethical questions from academic purists, they allow Ocearch to run a huge ship and buy the best equipment for scientists who work on the boat for free. And the more exciting results those scientists produce, and the more people who are following their work, the more sponsorship the organization can attract to sustain future work.

“Chris is abrasive and competitive, but it’s not easy to keep a group like that going,” says Pete Klimley, a retired shark biologist from the University of California at Davis who worked with Ocearch during the third season of Fischer’s show. Klimley admits he and Fischer had some difficulties—an understatement, considering Fischer had to settle with Klimley over payment for his stint on the show—but he also admires the bold attitude of his former colleague. “[Fischer] goes some place, and he says, ‘I have this boat, and I have some money to get you some tags, and you can do things you ordinarily couldn’t do because you didn’t have enough money for it,’” Klimley says. “That’s not a bad thing.”

In 2017, Fischer partnered with the private Jacksonville University, where students in the school’s marine science, engineering, film, and communications programs can use Ocearch as a learning platform. The organization has also escalated its collaboration rhetoric, making open-source research—meaning any scientist anywhere can access its app’s tracking data—a pillar of operations. “We’re on the cusp of a movement to transform science,” Hueter says. “As a scientist, you work on your own and you hold on to your intellectual property. But this approach to science is not working in a time when we urgently need data out there for policy decisions.”

Of course, scientists collaborate all the time. Massachusetts-based researcher Simon Thorrold, who gets samples from Ocearch expeditions, for example, also gets them from another colleague unaffiliated with Ocearch. And, in December 2018, forty-six researchers from all over the world released a paper laying out the work they all believe needs to be done in white-shark science. But none of that impresses Fischer. “I’m talking about radical collaboration,” he says. “They’ve come together, and yes, they’re collaborating, but they have no scale.” He wants scientists all over the world sharing data with each other through Ocearch. “It’s accelerating the pace of science so that we can do a better job of protecting the oceans,” says Hueter.

In Fischer’s ideal universe, no one would be worried about intellectual property or the intricacies of interpretation; they’d be concerned only with getting the facts out into the world. In a rapidly changing ocean, the clock is ticking. We live in a society bombarded day after day with devastating news about the environment, and we’re primed to be outraged over claims about the dire state of white sharks and the ocean. But what if these claims aren’t quite true?

Sharks had always been seen as trash fish, says Hueter, but after Jaws was released in 1975, shark panic spread across North America—turning them into man eaters. Populations started to decline from overfishing until the 1990s, when the US government passed a ban on fishing white sharks. Population estimates have since rebounded. (White sharks have also been listed as endangered in Canada since 2006, though some say the data that supported this designation was sparse.) While it’s true there is a “white-shark data deficit,” as Fischer often says, we likely aren’t actually running out of time. “There is no evidence that the populations are in trouble,” says Chris Lowe, director of California State University’s Shark Lab. And as for Fischer’s talking point about white sharks being a keystone species responsible for overall ocean health, Canada Research Chair in fisheries ecology Aaron MacNeil calls it “a really good guess, but we don’t actually know.”

In mid-September last year, Ocearch brought its bravado to Nova Scotia as part of its ongoing North Atlantic White Shark Study. It arrived on the province’s south shore to local fanfare and with a permit from Fisheries and Oceans Canada (commonly known as the Department of Fisheries and Oceans, or DFO) to tag up to twenty white sharks. Ocearch anchored near Hirtles Beach, a swimming and surfing hotspot, and the LaHave Islands, popular with kayakers, snorkelers, and scallop divers—and began chumming. Local resident Seth Congdon and two of his friends were mackerel fishing near Ocearch’s ship when he says a crew member told them about a white shark they’d earlier tagged and named Hal, after Halifax. When Congdon joked that they’d been swimming in the same water earlier that day, he says the crew member recommended he and his friends stay out of the water. They were chumming pretty hard, Congdon remembers the man saying. Word got out about the interaction when Congdon’s friend and local surfer Jefferson Muise went to the CBC after he says neither Ocearch nor the DFO got back to him with answers. Community members suddenly realized how little they knew about Ocearch’s operation. Ocearch’s chief science adviser, Hueter, responded by telling a community newspaper that the account was a “complete fabrication; never happened.” In a story published by Halifax’s The Coast magazine, MacNeil responded, accusing Ocearch of having only a “candy shell of science.”

Muise isn’t naive. He knows that in the summer and fall, when he’s out in the waves, he’s sharing the water with white sharks. And he’s familiar with the uneasy feeling, well known among surfers, when the water feels suddenly, inexplicably “sharky.” (Muise has a soft spot for the animals and even dressed up as Hilton once for Halloween.) He’s not wrong to be concerned. While scientists are still debating whether chumming could endanger people close to shore by altering shark behaviour, it’s not something many researchers are willing to risk. Heather Bowlby, head of the DFO’s Canadian Atlantic Shark Research Lab, travels offshore when baiting for white sharks. And Chris Lowe, who regularly tags sharks off the coast of Los Angeles, says, “There’s no way I’m going to chum or bait along a public beach.”

Fischer himself dismisses the criticism. Scientists who publish groundbreaking work have a better shot at getting academic funding. So, in Fischer’s mind, any biologist not interested in working with Ocearch is a data hoarder more interested in getting ahead than saving sharks. “We had to totally disrupt the whole way science was done,” says Fischer. “They don’t collaborate. . . . If you really look at any of them, they all have a different agenda. It has nothing to do with sharks.” Tell that to biologists who have dedicated their lives to this work, and you’ll get a different opinion. Lowe says Ocearch isn’t so avant-garde but, rather, at its core, is a scientific lab like any other. The only difference is that its facilities are mobile, allowing it to flit from location to location—armed with cameras and corporate sponsors and Twitter accounts—leaving disapproval and resentment in its wake.

There’s no middle ground in a revolution. Ocearch’s style might not be a good way to make friends, but it’s a great way to get attention.

The Writers’ Trust of Canada supported the author of this story.