“My name is John!” shouted John Allen Chau from his kayak in November 2018 as he paddled toward strangers on the beach of North Sentinel Island in the Bay of Bengal. “I love you and Jesus loves you!” In response, the people on the remote Indian island strung arrows in their bows. The twenty-six-year-old American missionary and self-styled explorer had elected himself saviour of the souls of the Sentinelese, an Indigenous tribe that aggressively resists contact with the outside world. Save for sporadic visits from an anthropologist with India’s Ministry of Tribal Affairs in the 1960s to ’90s, and two Indian fishermen who were killed in 2006 for venturing too close, the Sentinelese have rarely interacted with outsiders over the past century, making them immunologically vulnerable. Unfazed by the genocidal threat his germs posed and fresh out of missionary boot camp, Chau made repeated attempts to land—ignoring arrows and Indian law—in an effort to bring the Gospel to the Sentinelese. He didn’t survive. That he’s since been celebrated online as a martyr by Christian fundamentalists is sad but not surprising. More alarming is that Chau has been recognized, in profaner circles, for his spirit of adventure.

The New York Times ran with a headline straight out of Hollywood: “Isolated Tribe Kills American With Bow and Arrow on Remote Indian Island.” The article opens with “John Allen Chau seemed to know that what he was about to do was extremely dangerous,” emphasizing the risk and daring of the American’s undertaking. Only the fourth paragraph mentions a Bible, finally revealing the nature of Chau’s illegal mission: converting an Indigenous tribe, against its wishes, to Christianity.

Media coverage of Chau’s acts was disturbing because it didn’t come off as coverage of a crime—at least, not of his crime. Other major news outlets similarly valorized Chau’s legally and morally corrupt foray, highlighting his conviction as if tone-deaf temerity were a quality to admire. Laudatory remarks also came from within the adventure community. “Religious motivations of his trip aside,” Ken Ilgunas, author of This Land Is Our Land and Trespassing Across America, posted publicly on Facebook with a link to the Times article, “this guy seemed like a true adventurer at heart, and I feel a sense of kinship with anyone who dreams of going where they’re not allowed.”

As someone who has been called an adventurer before, I feel more of a sense of kinship with the person on Twitter who suggested this fix for the Times headline: “Remote Community Faces Biological Terror Threat From U.S. Religious Extremist Killed by Local Authorities.” To extol or glamorize any aspect of what Chau did risks condoning a brand of colonialism that should be anachronistic by now, and not just among missionaries. In fact, Chau’s evangelism is too easy a target, and it’s one that eclipses his more fundamental transgression.

So imagine that Chau wasn’t a missionary. Pretend he was just a sturdily secular young man with a winning smile and robust Instagram following, a dreamer who longed to go where he wasn’t allowed—and, to get there, ignored pointed suggestions that he wasn’t welcome. Does a lack of religious zeal change the tenor of his expedition?

Not at all. For what is still missing from this scenario is consent. In its place is a sense of entitlement as extreme as it is commonplace. Chau’s escapade, in the name of God or not, was nothing more than a violation: he was just another person who believed that the world was his to do whatever he wanted in and with.

W e tend to admire people who take risks and pursue dreams, but context puts a crucial warp on these platitudes. Surely it is not enough, in the abstract, to be adventurous or a dreamer or determined in the face of adversity. Rather, what are your adventurousness and dreaming and determination in service of? It was the Almighty, in Chau’s case, but what he really seemed to venerate was the small god of self-gratification. In this respect, when it comes to travellers of the most extreme as well as the most ordinary sort, Chau was no solo crusader.

This is true in a strictly religious sense: the Christian website Finishing the Task (FTT), for example, compiles the world’s remaining heathens-apparent into a convenient database, enabling freelance spiritual swashbucklers like Chau to advance the dark project of divine imperialism. “Here you can find the list of the world’s unengaged, unreached people groups that have no known full-time workers involved in evangelism and church planting!” the site enthuses. “Our goal is to remove a people group once it is confirmed that a solid church planting strategy, consistent with evangelical faith and practice, is under implementation.” According to the New York Times, Chau learned of the Sentinelese through the Joshua Project, which sources some of its data on “unengaged” people groups from the FTT list. When Chau’s death was reported in the media, 963 groups, including the Sentinelese, were on the prioritized-for-ministry list. FTT has since updated its list to only 343 groups, and the Sentinelese, post-Chau, are no longer among them.

Similar lists exist for the secular. If a missionary website didn’t galvanize the young American to seek out the Sentinelese, he might have found inspiration in Fodor’s or Reader’s Digest. Both outlets (among countless others) have run variations on a “top coolest places you can’t go” article, with North Sentinel Island listed alongside the Lascaux caves and the Svalbard seed vault as some of the world’s trendiest forbidden places. For self-styled explorers, other lists detail off-limits mountains, with sacred Navajo or Tibetan sites or havens of endangered species presented as alluring territory for adventurous dreamers. Climbing on certain peaks has been banned at the request of Indigenous peoples, yet these lists blithely urge readers to “click through and keep dreaming.”

Because there’s nothing wrong with dreaming, right? Or is there? Dreams can nurture a sense of entitlement that eventually finds expression, in some form, in reality. The average tourist might not add North Sentinel Island to their bucket list, but they probably share, to some degree, Chau’s longing to experience the outer edges of the world and a wilful blindness to the impact of being there. A certain breed of traveller craves visiting “untouched” places and interacting with “authentic” peoples, and a certain breed of tour operator promises to deliver you to and among them—for a price. Or rather two: one you fork over and one the place or people you visit must pay.

Survival International, a non-profit that works for tribal peoples’ rights, has documented a troubling rise in the popularity of “human safaris,” in which tourists seek out fleeting, zoo-like glimpses of uncontacted Indigenous peoples. In the Andaman and Nicobar Islands, part of the same archipelago as North Sentinel, you could, until recently (and possibly still), peer out of a tour bus at the Jarawa, a group of hunter-gatherers through whose traditional forest territory the Andaman Trunk Road was built. Similar sightings of Peruvian and Brazilian Indigenous tribes are available if you quietly ask the right guide. And, if these experiences aren’t thrilling enough, several organizations offer “first contact” treks, including ones in Papua New Guinea to visit “undiscovered tribes” who have “never seen a white man.”

Done well, tourism focused on local peoples can give them more control over their destiny and widen the hearts and minds of travellers to the wonders and complexities of the world. Done poorly, tribal tourism denies people the dignity of being left alone—denies them, even, recognition as people. Either way, travel has a tendency to bring out the Chau in all of us. We want what we want when we go abroad, which often is the untouched, the authentic—even as our arrival, by definition, undermines those very qualities in a place or of a culture and contributes to the slow, involuntary conversion of one way of life into another.

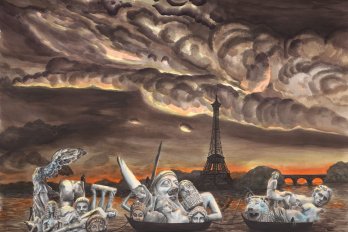

When Chau first attempted to land on North Sentinel, after bribing Indian fishermen to drop him offshore, a kid shot him with an arrow that pierced the Bible he was holding in front of his chest, or so Chau claimed in posthumously recovered letters. The scene he describes is suspiciously cinematic, possibly lifted straight from The Lost City of Z, a blockbuster film that details the exploits of twentieth-century British explorer Percy Fawcett who disappeared in the Amazon while searching for an ancient city. The film exalts the whole obsessive enterprise of exploration with lines from a Robert Browning poem: “Ah, but a man’s reach should exceed his grasp, / Or what’s a heaven for?”

Heaven, in this case, symbolizes noble striving at best or tragic overreaching at worst, and history is full of Fawcetts and Chaus and casual tourists crossing lines they shouldn’t have crossed to reach it themselves or to impose it on others. In one of his final notes, found after his death, Chau wrote, “Remember, the first one to heaven wins.” Perhaps we need an equally powerful line or image to encourage the opposite of grasping in travel: the virtues of humility and holding back. The poet Christian Wiman offers these words: “Once more I come to the edge of all I know / And believing nothing believe in this: ”

The blank space that marks the end of Wiman’s poem hints that there are things we cannot and should not know and places we have no right to go, not without invitation. British climber George Mallory’s famously glib answer as to why he aspired to summit Everest—“because it’s there”—doesn’t cut it anymore. When it comes to travel, how can we foster an ethic of restraint and reverence and the sort of curiosity not secretly convinced of its own superiority? A sense, if you will, of the sacred?

Respectful pilgrimages rarely make the history books or headlines, which is all the more reason to pay them attention. Consider the 1971 “antiexpedition” of Norwegian eco-philosopher Arne Næss and his friends to Tseringma, also known as Gaurishankar, in Nepal, a then unsummitted 7,181-metre peak sacred to those living in its shadow. In a pointed critique of mountaineering’s culture of conquering, Næss’s team travelled light, consulted with a local lama as to how high on Tseringma they could respectfully go, and invited villagers along not as porters but as colleagues. A few years later, other foreigners would claim the first ascent of Tseringma, but forget them. Remember Næss and team, who climbed to a certain height, took a look at the summit from a distance, and turned back.