The first thing that I saw when entering the Happy Place was a scene worthy of a dystopian children’s cartoon. One wall in the opening room featured a row of gumball machines (though none were actually operational), and at the far side of the space, there was an attendant whose job it was to hand out single M&M’s with happy faces stamped on them. Dozens of people milled about, and most had their attention directed toward the centrepiece: a pair of gumball–yellow stilettos, each about the size of a bus shelter. Visitors took turns sitting in the toe, hunching down with their hands gripping the sides as though they were getting ready to drive the shoe like a car. Each stared directly into a camera.

The Happy Place is one of the many “pop-up experiences” that now litter many of North America’s larger cities. Created in Los Angeles—seemingly as a response to the popularity of image-based social-media platforms like Instagram and Snapchat—the Happy Place, which came to Toronto’s Harbourfront Centre last November for a three-month run, describes itself as a multisensory experience: visitors walk through a series of rooms in order to look at the wacky set-ups and props, touch the odd decorations, and, in one, breathe in air that smells like cookies. For all intents and purposes, though, it is a sprawling, intricate green screen; its purpose is to provide guests with myriad photo opportunities to later post on social media, all for the price of $30 per person. It doesn’t matter how underwhelming, aesthetically lacking, or void of fun these experiences are in real life—the only thing that matters is that they look good online.

As the name suggests, the Happy Place is loosely centred on the theme of “happiness,” though its delivery on that promise is iffy. Its website contains the following creed: “HAPPY PLACE was created because we BELIEVE that our world today can use a lot more happiness. To make this DREAM come true, we set out on a journey to create a special place where anyone who walks in is surrounded by all things HAPPY.” (Emphasis their own.)

Even with this rich mandate, the Happy Place is, for the most part, interchangeable with the dozens of other pop-up, or so-called immersive art, experiences: they are spaces with bright colours, surreal scenes, and vaguely interesting conceits that manage to spur a fear of missing out among young people.

The trend arguably began in 2016 with the launch of the Museum of Ice Cream in New York. As its name suggests, attendees moved through a series of rooms that each had a loose connection with frozen dairy products—the most notable being a pool filled with faux rainbow sprinkles. The Museum of Ice Cream became famous for its online ubiquity on Instagram (and its long lineups), and was quickly followed by imitators, each featuring a unique theme of their own. There was the Color Factory in San Francisco and New York, with their rooms curated by hue; the Museum of Pizza in New York featured a pie that guests could sit in, and then there was the Museum of Selfies, in Los Angeles, which just seems reductive. Some experiences, like the recently opened Museum of Illusions in Toronto, are permanent attractions, but many are temporary affairs—as fleeting as a feed on social media.

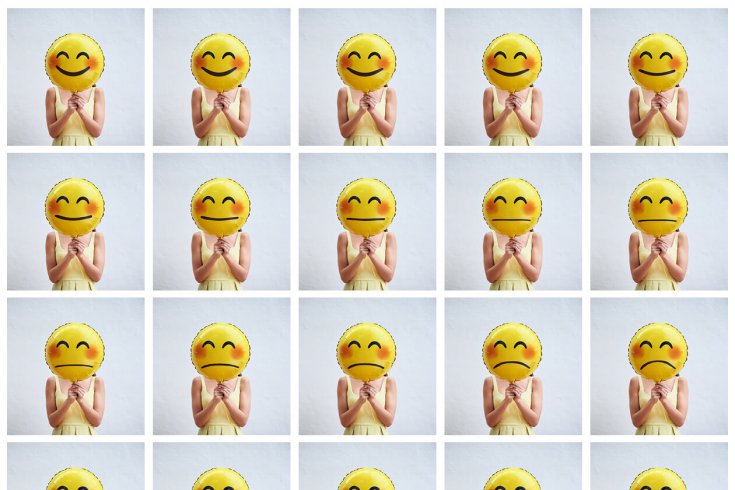

At the Happy Place, like at other pop-up experiences, the ready-made photo set-ups—a confetti dome, a giant cauldron that doubled as a ball pit—are near impossible to replicate outside of the venue: if a person wants the prized photo, they have to pay up. As I made my way into the latter rooms, I came to one section that featured rows of white chains that hang from the ceiling. I watched as a woman moved rapidly through a series of poses—looking over her shoulder, mouth agape in mock surprise, hands cupping her chin—in a manner that was reminiscent of vogueing. After thirty seconds of cycling through facial expressions and body formations, she rushed to her phone, operated by someone I assumed to be her partner (many people in the Happy Place seemed to have brought a loved one for the sole purpose of documentation) to determine if any met her approval. They must not have, as better instructions were given to the photographer and the process was repeated.

As guests move deeper into the Happy Place, the rooms come with enforced rules. Lines are formed, though they move quickly enough because, in some cases, each group is given about forty-five seconds to take pictures. When participants get to the ball pit, they are told that they are only allowed to jump in once. “You guys wanna do the duckys?” a worker called to a group near me. “The line’s right here.” The “duckys” referenced a claw-foot bathtub filled with yellow balls. The three surrounding walls were wallpapered with rubber duck patterns. A family was occupying the tub at the moment, and a second employee, wielding a phone, walked in a semicircle around it, taking shots from every angle in the hope that at least one would suffice. “You can’t come backwards, so if you want to do it . . . ” the first attendant stressed, trailing off. As she talked, she looked down at her phone and quickly refreshed her Instagram page.

The ducky room was what brought Magdalena Gizicki to the Happy Place. She made the decision to go with her boyfriend after seeing a photo of the tub in an ad; she had her heart set on getting some Instagram-worthy pictures in there for herself. Her experience, however, wasn’t as idyllic as she’d hoped. Gizicki told me that, while she was in the tub, she asked a staff member to take a photo of her throwing a yellow ball in the air by using her iPhone’s “burst” feature. Instead, the staff member took only a few regular snapshots, none of which showed the ball. “That was a disappointment for me,” Gizicki told me. “Once you leave one room, you cannot go back. I didn’t anticipate that. I did feel a little bit rushed when I was in there.” But the trip wasn’t all for naught: before posting her photos on Instagram, Gizicki went on the internet to ask advice on how to photoshop the missing ball into the air. She got the perfect picture after all.

The urge to seek out and photograph eccentric experiences isn’t a symptom of our collective obsessions with social media—it isn’t even a recent phenomenon. As literary scholar Terry Castle explains on her website, early photographers were staples at fairs and carnivals throughout North America around the turn of the twentieth century. “They came equipped with painted backdrops of Niagara Falls, beach, boat and other novelty props for comic portraits,” she writes. Part of their allure of these scenes seems to be that they offered guests a photo of themselves to take home and show to others—it was proof that the subject had gone somewhere and experienced something special.

Photography has long played a crucial role in how we shape the narrative of our lives. Milestones are documented, creating an archive that can be looked back on for years to come. But the value of facilitated photographs—whether a carnival’s fake backdrop of Niagara Falls or giant stilettos at the Happy Place—are a bit more difficult to parse. The photos are blatantly staged and not attached to important life events. Rather, they’re about creating evidence of having participated in a grandiose hypervisual event that mirrors that one-upmanship of social media.

But there is still a difference between old carnivals and the current crop of pop-up experiences. Carnivals and fairs always featured a range of activities for their guests—there were games, rides, prizes, and wonders of all kinds. Photos were a treat, a way to remember a well-rounded day. Guests at pop-up experiences appear to be there for one reason only: to document themselves in a place that has been carefully designed to give every attendee the exact same photos and, by extension, the same memories. At the Happy Place, for example, guests don’t have time to actually play in the ball bit—groups are given one minute, which is spent posing for a camera. The prize that guests are vying for at a pop-up experience is a photograph that racks up likes on social media.

I entered the Happy Place feeling skeptical of the organizers’ mission statement, but it should be noted that there is a science between aesthetics and happiness. Ingrid Fetell Lee examined the connection between the two in her recent book Joyful: The Surprising Power of Ordinary Things to Create Extraordinary Happiness. Using historical texts and scientific studies, Fetel Lee explains that bright colours, confetti, illusions, and clouds all have the ability to alter and uplift our spirits. “A body of research is emerging that demonstrates a clear link between our surroundings and our mental health,” she writes. “Joy isn’t hard to find at all. In fact, it’s all around us. The liberating awareness of this simple truth changed my life.”

Still, I found it difficult to feel particularly joyful in the Happy Place. I don’t think I was alone in this sentiment either. After moving through the room with the duckys, I entered the next area and found a three-dimensional XO sign not unlike the popular Toronto sign that sits outside city hall. I watched one woman climb inside the middle of the O, which was shaped like a heart, prop her feet upward and flash a smile worthy of a toothpaste ad. “Sorry, you can’t sit in the heart,” a timid employee announced. “I saw someone do it on Instagram yesterday,” the woman snapped back, and she proceeded with her photoshoot. When she was finished, she stormed away with her arms crossed.

And it’s this reason that the Happy Place does not seem very happy. Unlike the aesthetics of happiness that Fetell Lee outlines in her book, all of which can be found in the world at little to no cost, the Happy Place appropriates the aesthetics of happiness but offers few personal moments of joy. Everything has been carefully planned, directed, and timed, and the idea of happiness has been completely commodified. The result is an experience of vapidness.

There were, however, some moments of genuine joy I witnessed during my time at the Happy Place. As I stood near the exit watching people’s elaborate photoshoots within the confetti dome, I noticed a young child, no older than six, walking towards the exit with her parents. She had a pilfered pile of confetti clenched tightly in her fist. It was a small token, but at least it was something tangible.