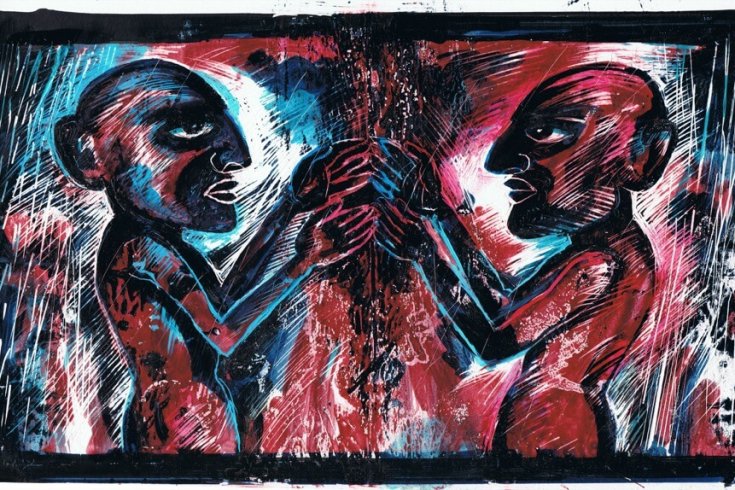

A DIVIDED MAN

For twenty years in a row the mechanic Tito from the town of Vlasenica in Bosnia had been named the best worker in Goose Feathers factory. Then his wife Rosa suddenly died. Some people said that she hanged herself when she found out that, instead of hair, goose feathers began growing on her legs. People just talk.

After that, Tito discovered nightlife and started leaving for work later and coming home earlier every day. His workday was getting shorter and shorter. He became afraid that one day he’d meet himself at the factory gate. One day in December this is exactly what happened.

“You lazy, good-for-nothing bastard. You’re late again. Aren’t you ashamed of all the medals you won over the years?” said the Tito who was leaving the factory. “Death to the working class,” replied the other Tito, who was coming to the factory just to collect his paycheque and go back to the pub. For a while they also met at the house, but stopped because the working-class Tito would be going to work just before the other Tito would be returning from the pub.

From then on they’d only meet on Sundays, when both of them would come to the cemetery to light a candle on Rosa’s grave. When their eyes accidentally met, they weren’t sure whether to hug each other or to pull out their knives. One Sunday in October the working-class Tito watched flocks of wild geese flying away and remarked, “Oooh, look how many feathers the factory’s going to lose.”

“Death to the working class,” commented the lazy Tito, watching the neon sign of his favourite pub, the Cooked Goose. He smiled when he noticed that the other Tito’s hair had begun to resemble goose feathers.

Some say that they never met again.

When the morning newspaper wrote that I was killed last night, I was walking down a Sarajevo street unaware that I was dead. I never read the obituaries. I never read the birth notices. All I ever read were the crossword puzzles and the reports on politics. I found them similar.

“The troubles are over for you, you lucky guy,” Lisa the Fox, the corner store owner, told me when I entered. She’d already phoned my children, she said, to tell them that they wouldn’t have to pay for any food they needed in the next two months. For decades, every time I entered her store, she’d clean the crow shit off my jacket. What changed stingy Lisa the Fox? I wondered as I was leaving. Why was she smiling at me? Over the years I only saw her smile once, and that was when she was strangling me because she thought that I was a shoplifter.

Then my former business partner bumped into me on the street. Tito the Wolf never used that street, because he said the crows always shat on me from the trees. During the past year he’d avoided meeting me after I took him to court after he’d cheated me.”I just called your children to tell them that I put some money in their bank account for their future,” he told me quickly. Before running away, he gave me a handkerchief to clean crow shit from my jacket.

Passing the restaurant where my wife Margareta the Pig and I often lunched for many years, I saw her through the window chatting and holding hands with our long-time lawyer and friend Harry the Snake. He never missed sending me a Christmas card and never missed sending me bills. Through the window I read from her lips that she had already told the children the truth and that she’d kept her promise to love me till I died. And now I had. Then I saw her asking the waiter to give me back our wedding ring and some napkins to clean crow shit from my face. I walked away, telling her that I still loved her. But I doubted she could hear me.

“What a horrible morning,” I said to my children when I came home. Instead of kissing me as usual, my daughter Jane the Crocodile and my son Malcolm the Dingo jumped on me and threw me into the bathroom, which I’d avoided for years. While they locked the door behind me, I saw them wiping crow shit from their shoulders. With my wig.

What’s wrong with my face? What’s happened to my broken wings after I put on my jacket? What’s wrong with the morning newspaper I still have under my arm opened at the crossword puzzle facing the political news? I’m still sitting here in the bathroom. Just watching my face in the mirror. And wondering why a flock of crows sits on my roof, talking to one another in a language I’d forgotten long ago.