“Take the third gravel road to the right,” went the directions to Larry Towell’s home in Lambton County, in rural Ontario. “Watch for lots of roadkill.”

On a March afternoon, threatening ice and snow, the landscape in Lambton has an austere, smouldering sensuality familiar to anyone who knows the photographs Towell has taken of his wife, Ann, and their four children. There are fields of tamped-down cornstalks and snow-streaked mud, breaks of trees barren and haunted, blurring up into a low grey sky, the brown river recently thawed. The farmhouses in this increasingly depopulated region tend to be plain, if not abandoned and dilapidated. But Towell’s home, set a kilometre or so off the main road on a bend in the river, has an elegant, funky aesthetic: tall, deep-blue trim crowned with cursive floral stylings, endless windows welcoming in floods of natural light from every direction, a water buffalo skull mounted above a neatly stacked pile of split logs.

When the fifty-four-year-old Towell answers the door, the wood-burning stove aglow behind him, he looks as though he could be one of the Mennonite farmers who live in the region. He wears a long silver beard, round tortoiseshell glasses, and suspenders stretched over a modest paunch, and projects a humble air of hospitality. One would hardly imagine that here, on a thirty-hectare farm in southwestern Ontario, lives a man who has been a member of the prestigious Magnum Photos agency; who currently has a new book, The World from My Front Porch, and a major career survey at the George Eastman House in Rochester, New York; and who hardly a week ago returned from documenting the impact of cheap retroviral drugs on people living with aids in Cape Town’s impoverished shantytowns — work that will be exhibited at the Corcoran Gallery of Art in Washington, DC, in June.

Both the Rochester exhibit and the book prominently feature images of his family, and though different in subject matter from the photographs that have brought him an international reputation, they are emblematic of his deeper themes and his approach to photography. In the tender and playful Naomi, Ann, 1989, a pregnant Ann and their young daughter are curled up naked on an old quilt, smiling with noses pressed together, light and shadow eddying and rippling over their bodies. In Naomi, 1992, a sullen Naomi stands against a stripped, scumbled wall amid the rubble and lumber of a ruined farmhouse. Above a darkened stairway, a cathedral window opens onto a tree and field ecstatic with white light. And in the brooding chiaroscuro Noah, Naomi, Ann, 1993, Ann leans out from the darkness to kiss her brother, Noah, on the forehead, light bursting from a window outside the picture’s frame, elongating the shadow of a pair of spectacles on the table where the shirtless Noah lies, flashing on his face and torso and a tuft of Ann’s long, dishevelled hair.

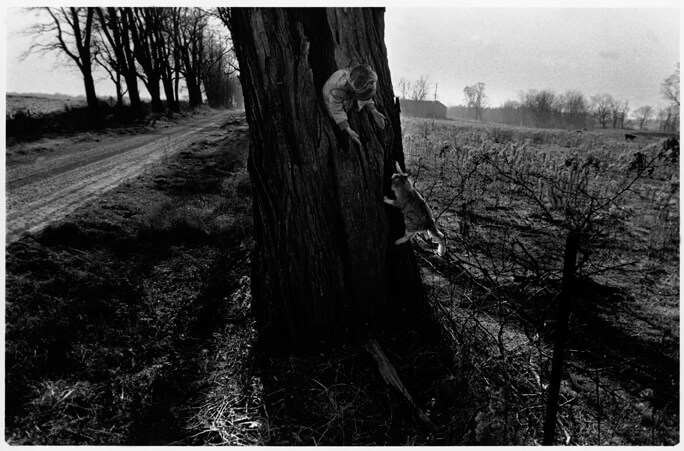

“They aren’t part of a larger project,” says Towell. “I just have cameras around the house, and when I see something I run out and shoot it.” But though these photographs form an extemporaneous family album of sorts, they are rigorous, emotionally complex, and thrumming with metaphors — about love, and intimacy, and family, and childhood, and innocence.

Towell’s work is above all about seeing: seeing what is there, seeing (or at least glimpsing) what it means to be a person. “We decline the artificiality of invention,” he writes in his introduction to The World from My Front Porch, “in exchange for the privilege of witness and the power of seeing.” And that is surely what the aesthetic of photography — and especially black and white photography, from Paul Strand and Walker Evans to Diane Arbus to the present, with its combination of precision and tactile sumptuousness and intimacy — is all about.

Unlike most contemporary photojournalists, who shoot with high-end digital cameras and print their work with ink and paper, Towell only uses traditional black and white film, whether he is in Gaza, Lebanon, or South Africa, or on his own back porch. “Black and white is still the poetic form of photography,” he says. “Digital is for the moment; black and white is an investment of time and love.” That Towell is concerned with the poetics of photography should come as no surprise. His meticulously realized compositions are saturated with the history of photography and the history of painting.

Towell studied visual art at York University in the early 1970s before moving on to poetry and music; he published several books of his poetry, and continues to record his idiosyncratic brand of folk music. But his impulse toward photography came from a different direction, one that is broadly moral and political. In the early 1980s, while he was living off the grid, teaching guitar, and tending his garden, he made his first trip to Central America. While travelling with a human rights group, he began taking photographs to illustrate the testimonies of the landless peasants in Nicaragua who rose up against the dictatorship of Anastasio Somoza in the late 1970s. “I became a photographer because I wanted to see it,” he says, speaking of how photography drew him in. “And it gave me an excuse to go there.” Bearing witness, seeing: one of the defining features of photography is that it requires the photographer to be there, the light and dark of the actual refracting through a lens and onto film.

Towell’s work is astounding in its coherence. He treats people facing poverty, dispossession, and violent conflict in the same spirit as his own family. “I’m really interested in how people survive, how families survive,” he tells me over coffee at his rustic kitchen table. Mother with Daughter at Grave of Son Killed by Death Squads, 1991, part of an extended series on El Salvador, has a dramatic, classical feel, evocative of a Pietà, but it depicts a wrenchingly intimate moment: in a modest cemetery dotted with small white crosses, a bereft mother sinks into the arms of her daughter before the grave of her murdered son, with the beautiful, sunlit hills of El Salvador behind her. In Guerilla Recruit, 1991, a girl who looks no more than eighteen stands topless, washing her shining jet black hair. Were it not for the AK 47 beside her, it would be easy to imagine her bathing with Towell’s children in the river beside his house on a lazy summer afternoon.

In Jacob Bueckert and Daughter, Temporal Colony, Campeche, Mexico, 1996, part of a picture essay on struggling Mennonite communities in Mexico and South America, a lonely girl in a head scarf turns toward her father at the head of the table. The scene has the pristine quiet of a painting by Vermeer. In Ben Reddekop Wake, Durango Colony, Durango, Mexico, 1996, a body is laid out on a table surrounded by figures shrouded in black, the room behind ablaze with light. All illustrate how, in Towell’s words, photography “can take that which is ugly and make it beautiful, not by misrepresentation, but by stopping to look more deeply at the subject itself . . . The ordinary becomes distinct, the way poetry transforms words. This handling of the ordinary is the life of photography itself. In this ordinariness, photography lives and breathes.” Photography has the power of redemption.

Although Towell has photographed some of the world’s most violent hotspots, he is by no means a war photographer. “The whole adrenalin world of war photography is white, Western, bourgeois,” he says. “The photographs of the violence are shallow. I’ve been photographing El Salvador for ten years. The newsy photographs are gone, but if you go into things deep, that work will stay.”

Towell’s approach to the Israeli-occupied territories and Israel’s most recent incursion into Lebanon has been, as he puts it, to “go narrow and deep.” In Sunlight on Street, Gaza, 1993, feet scoot away from a perfect triangle of sunlight on dark, oily pavement that looks spattered with blood. In a series of pictures shot during the second intifada, young men wield slingshots fashioned from found materials. And in the heartbreaking Boy in Destroyed House, Perimeter of Refugee Camp and Gush Katif Jewish Settlement, Khan Yunis Refugee Camp, Gaza Strip, 2003, a teenager smokes quietly in a house whose roof and walls have been ripped off, the neighbourhood beyond reduced to rubble.

In what may be one of the most powerful and emblematic images of New York from September 11, 2001, Towell photographed a man in a business suit standing in dust and debris, reading a scrap of paper that had fluttered down when the twin towers collapsed. “After some experience in conflict, I realized that violence is easy to photograph because it is already emotional and dramatic,” Towell writes. “Intimacy, the antithesis of violence — though often set against a background of violence and suffering — is actually more difficult to photograph than war, because hope is invisible.” A boy smoking and thinking in a ruined house, a man absorbed in a piece of paper that survived the slaughter of nearly 3,000 people — these are private, intimate moments surrounded by destruction, revealing glimmers of hope because they are testaments to people who survived.

Towell’s interest in “landscapes of destruction” began when he started shooting with a panoramic camera. But here, as elsewhere, his focus is on the human dimension. In these pictures, he explains, “rather than taking the traditional approach of looking at landscape through human beings, I look at human beings in the landscape. I use the panoramic in the same way I would use a 35mm, but with the panoramic the landscape is naturally brought up.”

Perhaps the most striking of Towell’s landscapes of destruction were taken in the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina. In one of the series, Waveland, Mississippi, September 5, 2005, a Catholic church is razed to its foundation, a sculpture of the Virgin Mary in the foreground, the glistening sea behind. Another is of a house that has been literally ripped open, its contents — mattresses, furniture, clothes, everything — strewn about, again with the serene sea in the background. Neither of these images has any people in it, but in a way human beings are a spectral presence. These are, after all, places where people worshipped and lived, places where their private and spiritual lives were sustained, exposed now in all their vulnerability to the forces of nature. Human beings in the landscape.

To get a tour of Larry Towell’s house is also to get a tour of its history, and of Towell’s history and sensibility. Vintage family photographs. Children’s drawings. Books. Endless guitars, including one that looks like it was made from an old oil can. Cameras. Knick-knacks. The leftover lumber from the beautiful, rough-hewn wooden floors in the extension he built to the original farmhouse was found discarded in a nearby forest. Some of the windows, which offer a view of the long fields he sharecrops out behind the house, were salvaged from ruined farmhouses back when he thought he might want to build a house of his own. “I’ve always been a junk collector,” he says. “As a kid, I collected feathers and bones in the woods; now at a clash site I bring all of this stuff back.”

In addition to reproductions of his photographs, The World from My Front Porch contains a generous sampling of Towell’s collecting habits: arrowheads, old family photographs, drawings and a rusty surveyor’s chain from Samuel Smith (the nineteenth-century surveyor whose house and land Towell now owns), slingshots made by Palestinian kids, bullet casings and missile shards, crude paintings made at his behest by political prisoners in El Salvador. Towell seems especially fond of the children’s drawings he recently brought back from South Africa. “It’s a habit I started in art school,” he tells me, “appreciating the beauty of simple things — things that aren’t in the art world but are art in the real sense of the word.” And that is perhaps the underlying point: Towell’s commitment to the redemptive power of beauty, the sense of hope that beauty inspires, is always rooted in the concrete reality of human life. Whereas digital images are for Towell ephemeral, photographs are unique things with histories, like bones and feathers.

If Larry Towell’s house has the idiosyncratic, homey clutter of the obsessive junk collector, his basement darkroom is all business. In the front room is a table covered with proof prints for his contribution to the Magnum aids project, for which he is on a tight deadline. On the wall is an archive of past and current projects. Then there is the long stainless steel sink, and a separate room for an enlarger on tracks projecting onto an old blackboard, which enables him to create oversized prints. He points out that he bought it cheap, because traditional photography is out of fashion.

“In photography, there are no words, only symmetry and emotion,” Towell writes. “There is a meditation to the still image however, that comes from stopping to look at the geometry of the world with all of our senses in order to capture a bit of it and confine it to one small space in recognition of a personal point of view. Photography casts aside the clutter, the commotion, and the noise of the world, in order to keep its form, shape and substance true to itself and in one complete thought.” He may be a purist who respects the hard discipline of art, developing and printing his black and white photographs in the basement of his house, but he’s by no means reductive. That’s why he brings home debris from the places he photographs. That’s why he records sounds from those places, and makes video sketches of them, such as Indecisive Moments, a video diary he made in the occupied territories.

Towell’s world is big and various, and not all of it is amenable to still photography. “When I feel like I’ve exhausted the material in a place, or there just aren’t any pictures,” he says, “that’s when I turn to video and sound.” But in the end what endures is that investment of time and love, the narrow and the deep, the poetry of simple things and ordinary life: his daughter wading into the Sydenham River with her two-year-old brother in her arms, the water rippling with light; five Mennonite women in identical dresses and broad-brimmed hats in Durango, Mexico, running through a wild, dusty gust of wind. “Your pictures are who you are,” Towell says. “The worst danger is losing your identity.