Let there be no love poems written

until love can exist freely and

cleanly. Let Black People understand

that they are the lovers and the sons

of lovers and warriors and sons

of warriors Are poems & poets &

all the loveliness here in the world

We want a black poem. And a

Black World.

Let the world be a Black Poem

And Let All Black People Speak This Poem

Silently

or LOUD.

—LeRoi Jones (Amiri Baraka), from “Black Art” (1966)

From the Hotel Theresa in Harlem, I crossed Seventh Avenue to the restaurant where I would bathe myself in the cuisine of the slave: grits and scrambled eggs, Canadian bacon, hash browns, and innumerable cups of coffee, which in the sixties, was extremely strong and real and fine, anticipating the special coffee shops you get in upper-class neighbourhoods today; and from the restaurant, I walked to the office of the New York Amsterdam News. Here I knew I would get help in locating James Baldwin, who was after all the reason for my being in Harlem. Somebody in the editorial department must know how to find Jimmy. I had already scoured the Red Rooster, day and night, from the previous Saturday.

The man who would provide this information was the most unlikely one on the entire newspaper staff. He was probably also, apart from the office cleaner, the lowest paid. He was the telephone operator. The man every person who called in had to talk to. The man who listened to every call: protest, complaint, congratulations, and as an extracurricular activity, a bonus on the monotony of saying, “Good morning, the Amsterdam News!,” and, when it was proper, “. . . and power to the people, Brother!,” making a date with a voice he speculated belonged to a body “built by Fisher,” a woman who might turn out to be “foxy.” Fred.

Fred accompanied me, after his shift ended at five o’clock, first to Small’s Paradise, to have southern-fried chicken with waffles and, of course, a double shot of Cutty Sark Scotch whisky and soda water; then through the barbershops where the gossip is more reliable than the news in the Amsterdam News and the New York Times, where you got another lecture on blackness, where you got your shoes shined, polished with your shoes still on, so diligently that you could feel the blood coursing through your toes; and a haircut if needed, as you relaxed in the womb of black popular culture, second in significance only to the Negro Church. Here, in the barbershop, one of many along Lenox Avenue, is the uncle of the Right Honourable Errol Barrow, the premier of Barbados.

And across the street from the barbershop is another Barbadian, a bibliophile and proprietor of the Frederick Douglass Book Center, a man who petitioned several mayors of New York, wrote letters to the New York Times, for years pleading, arguing, threatening, and eventually winning his case to change the name for the black population in America, and for black immigrants who come to America, when that name appeared or was used publicly, from “Negro” to “Afro-American.” The man is Richard B. Moore, a man who liked the books he sold more passionately than the customer who entered his bookstore to buy a book, so much so that he would refuse to sell a book that a customer asked for if he felt it contained a history of African culture in which he had a scholar’s interest.

A woman comes into the bookstore.

“Mr. Moore, boy, how?”

“How?”

“I looking for a particular book, boy.”

He recognizes her Barbadian accent. A bond is developed. He puts aside his formality of speech and he becomes a different man, dressed like a barrister-at-law, in white shirt, red tie, black jacket, and dark grey trousers. And brown shoes, polished deep into their cracks, and shining almost like the sun.

“And what the name of this book is?”

“I don’t really know. But it is about Africa. And the origin of names. And I trying to see if I had a’ African name, years ago, back in Africa. You know how I mean?”

“How you mean, ma’am! I know how you mean.”

“You could put your hand ‘pon this book, for me? You have this book in your bookstore? You think you could put your two hands on it, for me?”

Mr. Moore goes into the back of the store, where the shelves climb the walls to the ceiling; and I can hear him, blowing dust from the jackets, and see him in the small space looking into the shelves . . . and miraculously, he finds the book the customer is looking for. I can see him from where I am sitting in the congested store. And he wipes the book on the sleeve of his black jacket, and blows away the clouds of particles from the back, and he puts the book away, back into the shelves. And he returns to the customer. The customer is counting her chickens. But the news is sad.

“I sorry-sorry, ma’am, to have to tell you that I don’t have such a book. I can find you a book that is similar, though, ma’am. But I will keep looking for the one you want. I will keep looking . . .”

“You keep looking,” she tells Mr. Moore, encouraged. “You keep looking. ‘Cause I want to find out if I am a’ African. At least if I have a’ African name. I damn tired being called a Negro, in the papers, in this country.”

And gaily, like a woman giving herself the promise that the lottery ticket she has just purchased will bring in the “dookey,” she leaves the bookstore and swings back toward Seventh Avenue, and the Apollo Theater, with a smile of emancipation on her black face.

“I just couldn’t sell she this book, man. This book too important,” Mr. Moore says, holding the book to his chest, with both hands. The book is Muntu: An Outline of Neo-African Culture. It is written by Janheinz Jahn. It was published by Faber and Faber in 1961. It was first published in German in 1958.

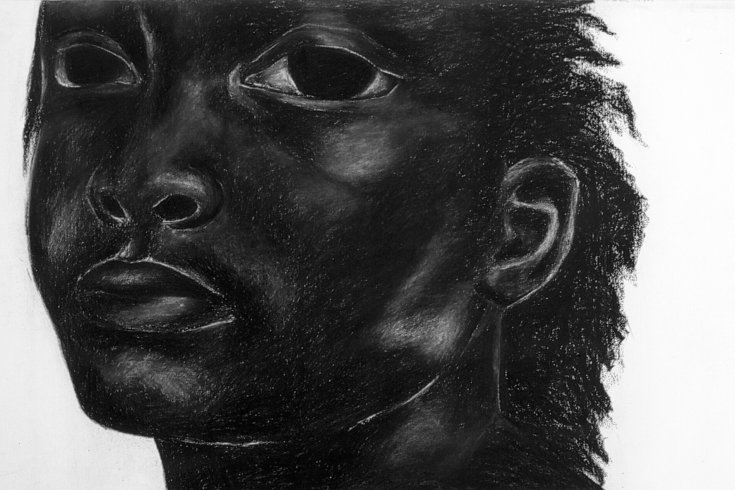

I wonder how this woman, who, from the way she looks, if one can make such a generalization, is a simple woman, and whose language, in her short conversation with Mr. Moore, does not exhibit a post-secondary education, has become nevertheless so intellectually fascinated with Africa and African names. But you know from her appearance, bright-coloured print dress, long to the ankles, with an African pattern and design, strong black features, as my mother would describe her, a mark like a tribal slash on her left cheek—more likely an accident suffered in childhood than an initiation into womanhood back in Africa—and fierce, black, shining hair coiffured into an Afro, and shining beads of lima beans, painted red, black, and green, round her promising, luscious neck, showing just that suggestion of sensuality round her breasts, you know this woman will get her way with Mr. Moore. And someday get her own copy of Muntu.

“This is philosophy!” Mr. Moore says. “Heavy reading! She won’t understand what Janheinz Jahn is saying, anyhow.” Then he said, “Coming up on Friday night? I making cou-cou and steam’ red snapper.”

This was an invitation I would not miss. And during my stay in New York and Harlem, looking for James Baldwin, I would accompany him home, on Fridays, when he closed his store, with a brown-paper parcel, wrapped and sealed with Scotch tape under his arm, briefcase in the other hand, and under that arm, a copy of the New York Times.

“She wouldn’t have been able to follow Dr. Janheinz Jahn! You don’t think so?”

“Muntu is some heavy shit!” I said to myself.

I never did invite my guide and new friend, Fred from the Amsterdam News, to Mr. Moore’s brownstone in Brooklyn. This was family, something to be kept within the clan, the Barbadian tribe; something I did not want to share with a black American. But Fred did not mind, because he did not know.

He continued to shuttle me round Harlem; showed me which steps to take to get to Father Divine’s temple; introduced me to some of the characters on the street, his friends included; and went with me religiously to the Red Rooster, to wait, like a detective, for James Baldwin to show up, while we listened to Marvin Gaye, while we drank Cutty Sark with soda water.

“Still looking for Jimmy?”

“This brother’s from Canada.”

“Canada?”

They did not think of Canada as a place where black

people lived.

“Did you say Canada? Now, ain’t that a bitch!”

“Brother’s from Canada. Looking for Jimmy . . .”

“Ain’t that where there’s all that motherfucking snow, Jack? Snow like a bitch, bro!”

“And when you find Jimmy, what you gonna do with Jimmy? Or Jimmy do with you?”

They all laughed heartily. I could not understand the reason for their merriment. But I knew that something “heavy was going down.” I would understand, later on.

“The brother works for the Canadian Broadcasting Company—cbc. Don’t you see this goddamn big, heavy Nagra tape recorder the brother’s carrying?”

“Been wondering what the fuck this thang be!”

“Jimmy’s in Greece!”

“Greece?”

“Motherfucker’s been gone, now . . . two-three months! Holidaying with them Greeks! And Giovanni. Ain’t that a motherfucker!”

“Jimmy’s gone!”

“Jimmy’s gone, yeah!”

“Tell me how long the train’s been gone!” And they shared slaps into opened palms. “Tell me how long the motherfucking

train’s been gone, brother!”

“When’s he coming back?”

“Jimmy may never come back. Giovanni’s Room, brother. Jimmy’s gone to Giovanni’s room, in Greece.”

“Thought Giovanni was Eye-talian!”

“Now, ain’t that a bitch!”

And Fred stepped in and made a suggestion. It was said in such an offhand manner, as if he was not serious, as if he was posing the question because he already knew the answer it would demand, and the laughter it would cause, and the impossibility of bringing it off.

“Try to get Malcolm. Get an interview with Brother Malcolm, brother.”

“With Malcolm X?”

Malcolm X, the man who had surrounded a Harlem precinct with hundreds of his followers after the police had brutally beaten and arrested a member of the Black Muslims on a trumped-up charge. He had then, with a wave of his hand, disbanded his followers, causing a police officer to say that he had too much power for one man; too much power for his own good; that it was not healthy for one man to have so much power.

I had read about Malcolm X in popular American magazines, especially Time and Life; and I had glanced at the pages of Muhammad Speaks, the official organ of the Black Muslims in America. But I was not up to interviewing Malcolm X.

At this time, I was aware of Malcolm’s rivalry with and disgust for Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., whom he regarded as a pork-chop-eating nigrah. This condemnation had great psychological implications: it cast aspersions on Dr. King’s dietary habits. The Muslims do not eat pork. And visiting their restaurant in Harlem, I had my surfeit of potato pie, since I could not buy a pork chop on Black Muslim premises.

“Yeah! Why you don’t interview Brother Malcolm, brother?”

I was terrified by the suggestion. And even though I had read as much as I could about Malcolm X, who was already challenging Dr. King for supremacy among the black masses, in ghetto and in slum, although I had read about him in Ebony, in Newsweek, and in the New York Times, I still did not feel I was up to this confrontation.

I knew a little about the streets of Harlem, both from the ordinary map showing the names of avenues and streets, but more importantly from the mouth of one of Harlem’s most illustrious sons, James Baldwin. This Harlem was Lenox Avenue on the west, the Harlem River on the east, 135th Street on the north, and 130th Street on the south. And Baldwin himself says, “We never lived beyond those boundaries, this is where we grew up.” And in 1937, the storefront church, at which he was the celebrated “boy preacher,” was the Mount Calvary of the Pentecostal Faith Church, on Lenox Avenue, known locally as “Mother Horn’s Church.” It was Mother Horn, the pastor of this storefront church, who asked the question, “Whose little boy are you?,” a question whose piercing cultural and racial irony followed Baldwin all his life, from that time in 1937.

“Whose little boy are you?”

Fred took me into every storefront church he could think of after we had visited the Muslim Restaurant on Lenox Avenue. This restaurant was historically singular. It did not serve anything made from pork. In Harlem? Who would dare to introduce these dietary restrictions in Harlem, a culturally pork-eating society? Hog maws, pork chops, barbecued ribs, the snout, the ears, the tails, the trotters—and Virginia hams—going to waste? Who is this new Messiah, this new Deliverer, to tamper with the fundamental backbone of Harlem’s culture?

This explained the insult Malcolm X levelled at Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. His face was always shiny. His face was always well shaven in its healthy appearance. And this is why—and for other reasons, of course!—Malcolm X thought Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. was a pork-chop-eating nigrah.

In the beginning, at the time I was trying to meet Malcolm X, there was this clear enmity: an absolute despising of the man, for his celebrity status, perhaps; for his success in leading peaceful marches in the image and philosophy of Mahatma Gandhi, which turned out to be brutal for those taking part in the marching. The Negroes—the term used in this time—in the thousands, tasted the unwrapped, brutal, nasty violence of their “fellow Americoons,” as soon-to-be President Lyndon Johnson seemed to say, a man who, like George Bush the Second, did not understand entirely the pronunciation of certain words. And in fact, if you looked closely, and without the white liberal perspective, you could see that white Americans regarded black Americans as coons. Take for instance the statements at this time of another distinguished white American, the novelist William Faulkner, about the civil rights movement and the peaceful Negro demonstrations for voting rights, particularly in the South. Faulkner lived in Mississippi and, like most Southern whites, advocated a “go slow” support of these demonstrations, warning white America—that is, the white North—that if this Southern attitude of “go slow” was ignored, there would be riots in the streets, and blood would flow.

And Faulkner thought fit to add, “If it came to fighting, I’d fight for Mississippi against the United States even if it meant going out into the street and shooting Negroes. After all, I’m not going to shoot Mississippians.”

Faulkner was asked if he meant to suggest that Negroes were not also “Mississippians.” He could not explain the confusion in his statement, and probably compounded it by saying, “No, I said Mississippians—in Mississippi the problem isn’t racial.”

I was getting tired, physically and emotionally. The southern-fried chicken, the chicken and waffles, the late nights listening to jazz in the Harlem clubs, the Apollo Theater and those clubs downtown, like the Five Spot and Birdland, had taken their toll on me. I was prepared to forget the interview of Malcolm X. I was going home. Home to Canada. On the new Underground Railroad, the Greyhound Bus.

The question asked of me, in my search to find Malcolm in Harlem, was the same, regardless of who asked.

“Why?”

I tried to explain to all of them: the waitress at the Muslim Restaurant; the man at the Muhammad Speaks newspaper office; the women dressed in long white dresses and white scarves that proclaimed a new, controlled, but nonetheless specific sensuality in this outfit meant to promote chastity and at the same time reverence of the black female body; and more than that, putting that black female body beyond the reach of the lasciviousness of the “nodding black man on the corner” and, in particular, from the clutches of the Man, meaning the white man who had had his fill of black women in various conditions of rape, of mistress, and of sadism. These new Black Muslim women asked the same question.

“Why?”

I could have said many things. But I found myself claiming a loyalty to Canada, for the time being: a loyalty that spat in the face of American racial segregation, a loyalty that presented Canadians, falsely, as morally superior to Canada’s “American cousins.”

“We,” I would tell them, mentioning the ethnic diversity in Canada, showing Canada as a symbol, Canada a neighbour, but superior to the United States. “We want to do an impartial interview with Mr. Malcolm X. We want to present him speaking in the narrative of his own words.” This seemed to please the waitress in the Muslim Restaurant.

This seemed to please the newspaper reporter. This seemed to please the man who phoned me about finding Malcolm. “We’ll get back to you,” the voice on the telephone said, and instantly I was cut off. I knew the meaning of this assurance. It had been said to me many times, applying for jobs in Toronto.

“We’ll get back to you.” the voice on the telephone said, and instantly I was cut off.

I knew the meaning of this assurance. It had been said to me many times, applying for jobs in Toronto. “We’ll get back to you.” I gave up hope. Even though the assurance had been spoken with a black voice. I decided to spend the remaining time visiting Greenwich Village bars, sitting in the same seat—the barman told me so!—at the Ninth Circle that Dylan Thomas had kept warm on that historic night, when he boasted of having broken all records for the number of whiskies drunk on this single seat; reading the Village Voice while pausing to drag my feet in the three inches of roasted-peanut husks that made a carpet on the floor; and dreaming of becoming a poet; and checking out Miles Davis, and Paul Chambers, and Cannonball Adderley, and Jimmy Witherspoon, and hanging out at the Five Spot.

I was tired of Harlem. Harlem was too intense in offering what it had to offer. The food was too rich. I had become a pork-chop-eating nigrah. The watching of men and women on the street corner was too intense. It was no longer a diversion. The soapbox speakers were proclaiming doom. And doom was too quick and instant for a life not yet lived. I had written no poems. “The fire next time” came through Baldwin’s nostrils like a prehistoric monster breathing fire. Harlem was preparing for a twentieth-century exodus back to Africa. All this feeling and emotion was like a too-rich curry, with chicken and basmati rice.

I was getting dressed to visit Basin Street, to hear Jimmy Witherspoon. I had never had too much love or appreciation for the blues. But I was keen to accompany some friends. As we were deciding on the time to leave, the telephone rang.

“It’s for you.”

I took the telephone.

“Mr. Clarke?”

“Yes.”

“Hear you looking for Mr. Malcolm.”

“Yes.”

“Why?”

I became nationalistic. I became Canadian. I thought I would use the pronoun “we,” so I said, “We . . . we at the cbc, the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation in Canada, want to portray Mr. Malcolm X, impartially, and we will publish everything Mr. Malcolm X says in the interview . . .”

“We will call you tomorrow morning. Nine o’clock,” said the voice of the man on the telephone. It was a deep voice. It was a sure voice. It was an intelligent voice.

“Congratulations, brother!” they all said.

“Let’s smoke some shit!” one said, offering me what was in his tobacco pouch.

“I’ll stick to Cutty Sark,” I told him. I took my own tobacco pouch from my pocket, and shook it, and got ready to stuff my Peterson of Dublin pipe, as I had seen Harry J. Boyle do.

We are ready now, Friday night! The eagle is flying tonight, Jack! And the four of us drove the Porsche, stick shift, and zoom-zoom, zoom downtown to Basin Street.

My brier is going like a well-attended fire. Coltrane is blaring through the speakers, and the automobile is filled with the fragrance of Estée Lauder Youth-Dew, which we all wear, because we read in a magazine that John Coltrane wears Youth-Dew, that every great black musician wears Youth-Dew.

“Yeah, man!” somebody says. And adds, “Because he’s trying to kill the smell of grass!”

We continue, zoom-zoom, zoom, to check out Jimmy Witherspoon at Basin Street.

“Everything’s Gonna Be Alright!”

And we become weakened by the power of his music, enervated; and we realize that he is talking directly to us; and I am in his thrall but I feel like the little boy facing Mother Horn, at the Calvary Church, nothing more, nothing less than a storefront, with the question, “Whose little boy are you?”; and I have no answer, just as the little boy had no answer.

Jimmy Witherspoon becomes separated from his sweating face. We are in a congregation, musician and audience, clapping, shouting, rejoicing. There is a dismemberment of face from torso. Suddenly, the face is on a vinyl disc. It is revolving at thirty-three-and-one-third revolutions per minute. The shouting continues. The rejoicing. Tambourines are beating against thick sweaty palms that have a lighter complexion than the back of the same hand, and the palms are tough leather, scarred and calloused, and hardened by manual labour in the winter. And my head is spinning, too.

Two hours later, on the way back home to the brownstone, someone says, “The brother talked like a motherfucker! Never knew the brother could talk so much shit, Jack!”

“And the number of raw oysters he eat? At least five servings!” another voice says.

I was in another world.

The next morning, the telephone rang. It was nine o’clock. We were already up, going back over the drama and the humour of the previous evening. And the telephone ringing did not interrupt our teasing. And no attempt was made by anyone else in the brownstone to answer the telephone. It seemed as if they all knew it would be for me. So I went to the telephone.

“This is Malcolm X.”

It was the same voice as last night’s caller.

[click here to listen to Austin Clarke’s interview with Malcolm X]