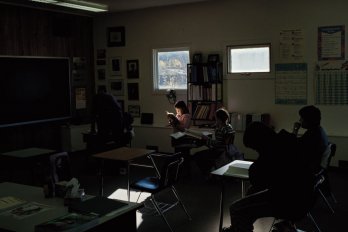

By 6 a.m. on Saturday, December 2, a not-unusual clutch of characters had gathered inside the Rose Donut shop at the corner of Carlaw Avenue and Gerrard Street in east Toronto. Situated in a strip mall, alongside P. K. Fung’s family medical practice, the Big Yard Groceries & West Indian Take-Out (now for sale), a pharmacy, and Coolie’s Bar & Restaurant (with its all-day breakfasts and karaoke nights), the Rose could be anywhere Canada. I go there most early mornings for coffee and to read manuscripts. The shop’s atmosphere — the low babble of a television, the bling-bling of video-game machines, the odd crank talking to himself — helps me concentrate, and on this day there was much to consider.

Leading up to the Liberal convention, in Toronto salons, faux British pubs, and other non-U establishments where the leadership candidates were on parade, there was discernible jealousy that the action was taking place in Montreal. And now the day had arrived and the king would be crowned, but at the Rose, as the sun lifted into view and the morning newspapers were delivered, there was no mention of it. Bleary from a late night at downtown dance clubs, two young men played Chinese chess (xiang qi) as friends looked on, offering advice or critical barbs. One game led to another, the onlookers became players, the others judges. Scores were kept. Next to them sat the lone and elderly white man, as always unshaven and unkempt, a regular who talked to no one in particular about hockey or Pearl Harbor, adding a monologue about the perils of global warming to his verbal sketch.

A black woman pulling a bundle buggy — the contents shielded by a blanket and cardboard siding — entered the shop, positioning herself across from the lonely talker and, eventually, taking the bait. On global warming, she had her own views. “The weather’s too cold… wind everywhere, can’t keep my hat on,” she said, before asking, “When does the No Frills across the street open? ” Pleased to be noticed, the old man said “nine o’clock” and then detailed the horrors of a world gone hot. The woman went silent, stirred her coffee nervously, and descended back into her own solipsisms.

For three years I have started many days at the Rose, and it has never struck me as a mise en scène emblematic of Canada, Canadians, or anything at all. By 8 a.m. on this Saturday, other, less frequent customers had arrived, newspapers were being opened, and more animated talk obscured the sounds emanating from the television. The discussions around me were not about nationhood or leadership, or any other high concept removed from the realities of the working poor, domestic violence, expensive public transit, and crummy weather. And why would these denizens of the Rose be interested in the current language of state? In the week prior to the Liberal convention, words spilling forth from Ottawa had devolved into idle but dangerous abstractions, the rhetoric rootless but still capable of ending Canada before it has fully begun.

On November 27, 266 out of the 308 members of the federal Parliament stood behind Prime Minister Stephen Harper’s motion that the “Québécois form a nation within a united Canada,” a statement replete with abstract nouns and, this being Canada, a hopeful adjective. Two of the more curious supporters of the motion were Stéphane Dion and Michael Ignatieff, in the end the final contestants for the leadership of the Liberal Party of Canada. Dion is the author of the 2000 Clarity Act, a tough piece of legislation meant to keep Quebec sovereigntists (les Québécois?) quiet and Quebec (the territory, the province) inside Canada. In the event of a referendum on independence, the act lays out clear rules for the gamble itself and a clear process after a vote to separate. This was national-unity legislation, and Dion did not mess around. So why would he support something as murky and craven as Mr. Harper’s motion?

Michael Ignatieff is the author of Blood and Belonging, a six-part book (including a fascinating chapter on Quebec) which suggests that ethnic nationalism is symptomatic of failed states, and that for a country to be a country ethnicities (and regions) must sublimate their urge for recognition in favour of the higher calling of civic nationalism. Buying in requires sacrifice but it also provides glue; and as Ignatieff insisted repeatedly on the campaign trail, this elevated social contract represents “the spine of citizenship.” And yet, there he was, a newly minted Member of Parliament and Liberal leadership aspirant, some weeks after issuing his own statement that “Quebec is a nation,” voting in support of Harper’s motion, a brand of nationalism based on ethnic identity, if not blood.

The Bloc Québécois — its very name connoting ethnic nationalism, its existence in the national Parliament suggesting a failed or weak state, or a state unconcerned about longevity — agreed with Mssrs. Harper, Dion, and Ignatieff, and the overwhelming majority of our federal representatives. On cue, after the motion passed, the Bloc then exercised a purposeful elision by announcing that “Quebec is a nation,” full stop. As the hopeful conditional “within a united Canada” did not aid and abet the separatist cause of independence (to be achieved by 2015), the phrase was dropped.

His meddling done, supported overwhelmingly by Parliament, and with the country more “asymmetric” than ever, Harper skipped off to Latvia — once a province, now a nation — to troll for help from nato partners for his misadventure in southern Afghanistan. For his efforts, the prime minister was told that Canada is not nation enough to ask for military assistance in Kandahar Province (where, after all, the locals are rough customers, with guns, religion, and opium), that this chapter of the Great Game is unwinnable, and that the nato partners, if they joined at all, would sequester themselves in the relative calm of Afghanistan North.

As the prime minister engaged in high-stakes failed diplomacy, back home the Assembly of First Nations got up to its own mischief. Given the olive branch extended to the Québécois by beneficent Ottawa — or at least to some of them; or perhaps to all those excluding the Anglos, the northern Cree, distrusted allophones, and the Haitian cab drivers clustered miserably at Place Bonaventure in Montreal — Phil Fontaine, head of the afn, exercised another purposeful elision. He insisted that aboriginals, as first peoples and being original, thus also deserve nation status — even though, given that they are recognized as the Assembly of First Nations, one would presume that their nationhood has already been conferred. (That certain legal and constitutional experts argue that the Québécois’ new status holds no legal or constitutional water is, in this field of gravitational politics, almost entirely irrelevant.)

Civic nationalism, it could be argued — though outside of the Rose Donut shop few arguments make sense these days — involves rights and responsibilities, giving as well as taking. But after bouts of celebratory drinking, restorative sleeps, further kicks at the federal can, and sober second thoughts, the fact remains: the Bloc, the first newly spoiled child of Confederation, continues to demand billions annually from Ottawa (to pay for Quebec’s education, health care, policing, and probably for the propaganda materials necessary for the next referendum on independence). At the same time, the afn (now nations squared, I suppose), in their turn, demand that billions flow their way. And why not? In this new game of Canadian realpolitik, the idea is to hold hostage any institution naive enough to think anyone anywhere gives a tinker’s damn about anyone other than themselves.

Thus: “Be it resolved that the Québécois are a nation within a disunited Canada; that the Atlantic provinces, being no longer contiguous with the rest of Canada, are now free to do as they please (we can be very helpful to others); that the federal government is an existential construct, a being for nothingness, but useful as a cash register; that Ottawa extend billions annually to sovereign Quebec, preferably in large sacks of $20 bills, for easy distribution; and, finally, that it be constitutionally recognized that separateness is etched in our dna, as are bad manners, hissy fits, greed, and other deadly sins.” Being reasonable, it was so resolved.

Thus: “Be it resolved that the aboriginal peoples of Canada are constitutionally recognized as a founding nation and a third order of government, are dirt poor and deserve compensation immediately, and are justifiably mad as hell at all other orders of government for high crimes and misdemeanours.” Being reasonable, it was so resolved.

Thus: “Be it resolved that I, Ed Stelmach, the new premier of the province of Alberta, being a reasonable man in unreasonable times, quite admire this nation-within-a-nation thing that Quebec has and which the aboriginals will surely soon have, and that Alberta will be demanding the same (once someone somewhere tells me exactly what we are talking about); be it further resolved that the government of Alberta Nation believes in not governing — that is, our nation will be unique, and therefore will be justified in receiving nation status and all the extant powers that this entails, by virtue of the fact that it will never, under any circumstances, involve itself in, slow down, or regulate the economy.” The sentiment of the times being live free (from responsibility, from giving) or die, it was so resolved.

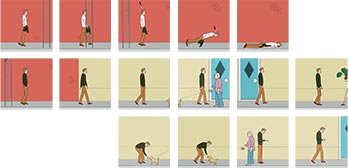

Back at the Rose Donut shop, the clock struck nine, and at that precise and precipitous moment a town crier stormed in brandishing copies of the Declaration of Independence, Hamlet, and Being and Nothingness. “This room is filled with the state’s non-being,” shouted the cloaked figure, before dispensing his texts to the collected few. “Your masters are playing games of chance and semantics. At first glance they appear harmless, but they are not. You must fight back or you too will become disassembled. First, you must become one, and then you must become none.”

Short hours later, emerging from the fog of abstractions, the newly formed Rose Collective issued the following resolution: “We may look like a Bantustan, but we are a republic with the powers of direct taxation (no taxation without representation), with our own militia (to guard us from distant, aloof, and acquisitive foreign governments), and laws allowing our citizens to shoot stray dogs (in case the food runs out). We adopt these measures with some reluctance. Given that Canada has been sold, bartered away, and no longer exists in any meaningful sense, what choice did we have?”