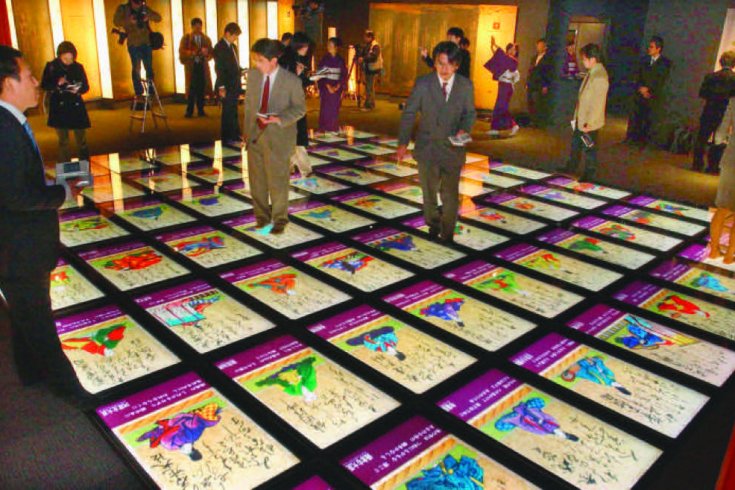

Kyoto—My competition looks fierce: elderly couples with canes and surgical masks. In their favour: the game is one they’ve known since childhood. In mine: familiarity with the technology. My hands are gripping a customized Nintendo DS system whose screen is lighting up with digital watercolours. Each must be matched with one of seventy larger images spread out across a giant floor of plasma screens beneath my feet. When I scramble atop the correct image and click to indicate a match, a motion sensor in the ceiling is triggered. The DS chimes in approval, then brings up the next watercolour. The player with the most matches in two and a half minutes wins.

This battle royal is taking place in Shigureden, an interactive museum dedicated to the poetry card game uta karuta. The basic “deck” for uta karuta is the Hyakunin Isshu, a compilation of one hundred poems by one hundred poets originally assembled by the thirteenth-century imperial poet Fujiwara Teika. During the Edo era (1603-1867), the poems began appearing on playing cards in the houses of Samurai and Shogun nobles, and a game soon emerged in which a reader would sing the lines of a poem and players would scramble to be the first to pick up the matching card. Over the centuries, uta karuta grew into one of Japan’s most popular pastimes; memorizing the poems remains part of the curriculum in some Japanese schools.

Built by the tranquil waters of the Hozu river, framed by cherry blossom trees and a rock garden, Shigureden was partly financed by Hiroshi Yamauchi, the former head of Nintendo, the Japanese video-game-console maker. In a sense, the museum is the most ambitious amusement Yamauchi has ever made, striving as it does to bridge the generation gap in Japan by marrying the country’s rich cultural past with its technological savvy.

Nearly a century before Super Mario stomped his first turtle, an artisan named Fusajiro Yamauchi had a small business hand-making playing cards in Kyoto. His company, called Nintendo Koppai (” in heavens hands”), quickly grew into Japan’s leading card maker, thanks largely to a game he marketed, called Hanafuda, that was well suited to gambling and thus to vast profits for the Yakuza mafia. Over the years, Nintendo turned out other card games, including versions of uta karuta. Then, in 1985, under the direction of Hiroshi, Fusajiro’s great-grandson, the company launched the Nintendo Entertainment System. The small grey console introduced millions of under-eighteens worldwide to the adventures of a red-capped Italian plumber and gave birth to the multi-billion-dollar era of the electronic-entertainment industry. Today, Nintendo holds around $10 billion (US) in assets, and even though stiff competition from rivals Sony and Microsoft has eroded its market share, the company still made nearly $5 billion off its games and systems last year.

With an eye toward the family tradition, Hiroshi Yamauchi, who retired recently at age seventy-eight, offered funding and technical support for Shigureden. As a business and marketing project, the museum has been a resounding success, drawing up to 700 visitors per hour on weekends since opening in January. But achieving Yamauchi’s deeper cultural goals—bringing card games to life for young gamers and convincing members of his own generation that video games are a legitimate cultural enterprise—may prove tougher.

“In past years the old and young had no common [spaces] in life concerning entertainment,” says Katsuhide Tsushima, a professor of digital games at Osaka Electro-Communication University. A trained nuclear physicist and specialist in artificial intelligence, the solidly nerdy Tsushima (he keeps Star Trek models in his office) is the president of Japan’s Game Amusement Society, a consultant for the video-game maker Konami, and the inventor of something called 4-D Tetris. Now in his sixties, he is also, he tells me, a former regional uta karuta champion. Tsushima has visited Shigureden but found Nintendo’s stylized electronic version of the game duller than the old-fashioned playing cards. “Video games are still for young people who aren’t as creative,” he says dismissively. “Game makers are aiming to make young people avert their eyes from Japanese tradition and culture.”

Tsuyoshi Kanda begs to differ. Kanda, thirty, works by day in the marketing department of the Osaka-based game maker Capcom. At night, he guides tourists through traditional tea ceremonies in Kyoto. Equally comfortable serving tea in a samue (an initiate monks robe) and juggling two cellphones in business-casual attire, Kanda embodies both old and new Japan. “Video games are becoming more accepted into Japanese culture,” he says. “I think Mario and Pokémon will be as important as literary characters one day.”

Pokémon, a fictional species of characters created by Nintendo, actually gained renown among the world’s children thanks as much to a trading-card sequel to the original video game as to the video game itself, so perhaps the young are not entirely leaving behind the pastimes of the old. For my elderly rivals at Shigureden, where time is running out on our game, the familiar pictures and verses of the Hyakunin Isshu offer a palatable entry into Nintendo’s world. As my screen counts down to zero, I rush to match one last poem, a lament to fading beauty written over a millennium ago by Komachi Ono:

The blossom’s tint is washed away

By heavy showers of rain;

My charms, which once I prized so much,

Are also on the wane,

Both bloomed, alas! in vain.

In other words, Game Over.