The first time I shared a meal with Zacharias Kunuk, we were squatting over the steaming carcass of a freshly killed seal, eating its liver raw. The next time, we sat next to one another at a long table in a downtown Toronto restaurant. Kunuk was hesitating over the lengthy Italian-themed menu. “What are you having” he asked. “Veal cutlets,” I said. He opted for beefsteak, medium. The wine was Zinfandel Primitivo.

Earlier on that February evening, Kunuk had been standing before a packed auditorium at the Ontario College of Art and Design (ocad). The inaugural guest of the 2006 Art Creates Change lecture series, he introduced excerpts from two of his earlier video works, an episode from his thirteen-part television series, Nunavut (1994”“1995), and My First Polar Bear (2000), a documentary about the importance of the animal in the arctic hunting tradition, as well as a clip from the documentary on the making of his much-anticipated second feature, The Journals of Knud Rasmussen. Kunuk’s first feature, Atanarjuat: The Fast Runner, won the Caméra d’Or at Cannes in 2001. Shot last year in Igloolik, Rasmussen will open the Toronto International Film Festival in September.

Based on an Inuit legend, Atanarjuat: The Fast Runner tells the story of two families driven apart by a shaman’s prophecy and the struggle of the next generation as they unwittingly make the same mistakes as their forebears and perpetuate the curse. As Kunuk wrote, “Atanarjuat wasn’t the only legend we heard but it was one of the best—once you get that picture into your head of that naked man running for his life across the ice, his hair flying, you never forget it. It had everything in it for a fantastic movie—love, jealousy, murder, and revenge, and at the same time, buried in this ancient Inuit “action thriller,’ were all these lessons we kids were supposed to learn about how if you break these taboos that kept our ancestors alive, you could be out there running for your life just like him!”

On first viewing, Atanarjuat is perplexing. The opening is elliptical, stirring a nagging sense that readers of subtitles are being left out of the whole picture. A group of Inuit is inside what appears to be a cave; the only light comes from flickering seal-oil lamps. A cackling old man in the midst of a slightly apprehensive group compares his coat with that of a younger man; the old man is a stranger. Then two men are tied together to perform some kind of test of strength. One dies. A younger man then accuses the survivor of murder.

Unlike the typical foreign-language film-viewing experience, the number of syllables uttered by Atanarjuat’s actors doesn’t correspond with the basic sentences printed along the bottom of the screen. The actors are inexpressive compared with those in mainstream movies, particularly in the close-up, the shot that lifted the cinematic form from carnival curiosity to mass entertainment. Indeed, the whole film defies classical shot structures: typically, there is no establishing master shot but rather one continuous shot that is broken by jump-cuts and cutaways. As for what is actually happening, no one gets it the first time through: Something bad is taking place but you’re not certain what it is. Yet the rhythm, once established, is mesmerizing. It’s like listening to Kunuk speak, like being there.

You don’t have to travel to Igloolik to appreciate the art of Zacharias Kunuk but it helps, if only to apprehend the vast whiteness that is his canvas. I did last April, to visit the set of Rasmussen, 3,000 km north of Toronto. I asked him if we could have some time together. He nodded, told me where to go, what time. A couple of hours later, I was watching him smoke endless cigarettes in a barely insulated back room of his modest Igloolik home.

Spend some time with Kunuk and be prepared to wait. It’s a matter of pacing. Ask him a question and he looks elsewhere. He thinks about it so long you might think he didn’t understand you. Seeing him outside of his milieu one suspects he’d rather be home. Admirers greet him with outstretched hands but his expression is neutral; they gush and he nods once. When asked, during the questions after the talk at ocad, if he would consider living and working in any other environment, he replied, “I want to stay. I know the area. I don’t picture myself making other people’s stories.” Later, during one of the evening’s many smoke breaks, he just said it outright: “I want to be hunting with my friends in “”27?c.”

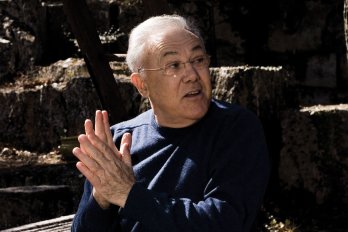

It’s not possible to write about Kunuk without introducing his partner, Norman Cohn. Cohn was not at dinner; he was in Paris presenting Rasmussen to potential international sales agents. An American, Cohn was a hippie videographer in the 1970s—he has shown his work at the Venice Biennale and the Art Gallery of Ontario—until he became bored with the self-referential nature of video art. In the early 1980s, while living in Montreal, he happened on the video work of Kunuk and Kunuk’s late mentor, Paul Apak, and found, as he puts it, “partners with similar vision and shared goals despite wide cultural differences.” That’s something of an understatement: Cohn was born in Manhattan—” 103rd and Broadway”—in 1946; Kunuk was born in 1957 in a sod hut in Kapuivik and didn’t move to a settlement until he was nine.

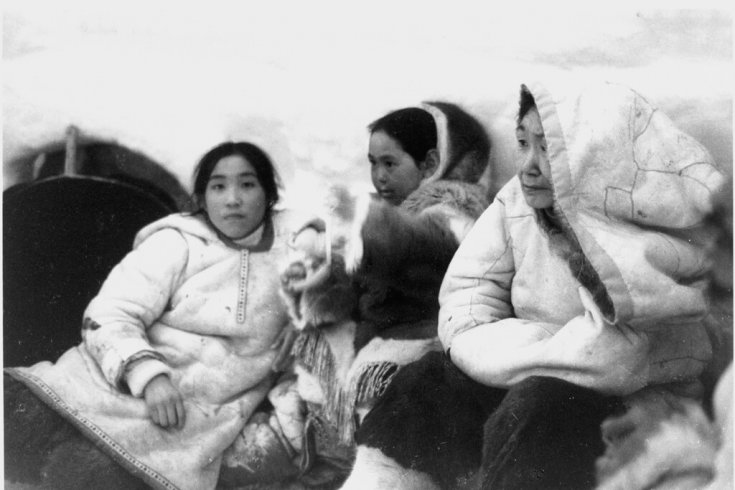

Igloolik is an island community off the coast of the Melville Peninsula, and it makes a compelling local case study. In 1973, and again in 1977, local residents rejected government offers to deliver English-language radio and TV by satellite. “We saw what happened to other communities who had it,” said Kunuk. “It changed their lives. They stopped visiting each other.” With the introduction of consumer video cameras, however, Kunuk recognized the potential of recording his father’s hunting stories and the elders’ storytelling. The 4,000-year-old way of life of the Inuit was in danger of extinction, and Kunuk’s project was to recreate it as it was lived with the specific intention of perpetuating the traditional ways. A talented sculptor, Kunuk sold some carvings in Montreal in 1981 and came home with a camera and recorder and the community’s first television. His initial efforts were in black and white because he could not figure out the controls. Apak, the local producer for the fledgling Inuit Broadcasting Corporation, hired him as a cameraman in 1983.

Cohn travelled to Igloolik in 1985 to give a camera workshop and stayed on to live. He has collaborated with Kunuk and Apak on every project since—they founded Igloolik Isuma Productions in 1990—including Atanarjuat, released three years after Apak died. Nonetheless, Cohn stands back and allows Kunuk to have the spotlight. Kunuk is the official director of Atanarjuat but both men share nearly every job category and Rasmussen’s credit roll will reflect that: co-screenwriters, co-producers, co-directors. Lately, Cohn has also handled the videography.

Since hunting is of necessity central to traditional Inuit culture, Kunuk’s early works are in essence wildlife films. For a southern audience, a wildlife film has a specific connotation: animal preservation. From the Undersea World of Jacques Cousteau and Mutual of Omaha’s Wild Kingdom to the more rarefied musings of Jane Goodall and David Attenborough, beyond a certain First World sentimentality, all have in common that the only killers are animals.

In the cool arctic world of Zacharias Kunuk, animals are in focus all right—within the crosshairs of a rifle. Viewed in an uninterrupted stream of videotape, one ticks off the checklist of species killed in action: whale, polar bear, walrus, caribou, seal, Arctic hare, loon, and salmon. Even the caribou’s parasites wind up in a human gullet; the hide, flopping amply now that its owner is in a pot, abounds with lice, a delicacy favoured by children.

Kunuk understands the high-contrast value of blood on snow. The tableaux he presents would disgust a vegetarian: these are family picnics from a horror film, the rich gore spread like a floor-level buffet. In episode nine of Nunavut, entitled “Aiviaq” (Walrus Hunt), the camera watches over the shoulders of two hunters at the prow of an open boat putt-putting toward an ice floe. Occupying the centre of the screen are two walruses, a behemoth bull and his cow, like fat tourists lounging on a beach about to be set upon by cannibal pirates. “Want to shoot” asks one hunter. “You haven’t shot one in a while.” The gun kicks, the cow drops, her mate stands oblivious. Then he too is dispatched, his huge bulk rolling into the sea, blood jetting into the surface foam.

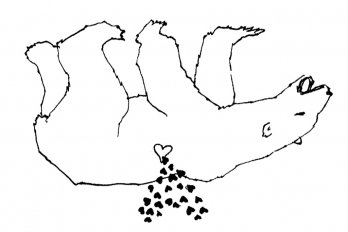

In My First Polar Bear, the bear is hunted over a number of hours, run down and tired out; the sled dogs are baying for his blood. Then the prey is within range. The bullet registers as an insult, the bear turning on one of the circling dogs as though it had bitten him. The animal urgency starts to register when the bear begins vomiting blood. The bear staggers, fatally punch-drunk, then collapses. What follows is an anatomically exhaustive lesson in butchery. The hunters approach the massive animal and roll him on his back, compare his paws with their measly mitts, then pull out their knives and help him out of his birthday suit. The moment comes when the bear’s stomach is cut open and its contents sluice out, revealing an intact seal flipper. Kunuk’s unblinking camera completes the circle: What goes around comes around. “We show it as it happens,” Kunuk said.

The steak consumed, the internationally renowned filmmaker retired to the patio for an Export A. Another dinner guest asked him how old the bear was. Kunuk shook his head. “No idea.” How much does a bear like that weigh He shook his head. “No idea.” What sort of rifle do you use “A point two-forty-three.” Kunuk is not an animal expert. He’s an expert at killing animals and harvesting their bounty.

Cohn describes Kunuk as a hunter who happens to make movies. Indeed, it’s tempting to describe Kunuk in cuddly terms until you’ve seen him plug a bobbing seal at fifty metres with his rifle. Kunuk’s view through the camera is similarly uncompromising. Cohn has spent the better part of twenty years in the company of Kunuk, and no one knows him better. “The idea that the job of a filmmaker is to travel would to him seem sort of insane,” said Cohn, when I visited his Igloolik shack last April. “Our style is inside looking out rather than vice versa, the community expressing itself to itself and others are welcome to watch.”

While Kunuk the hunter continues his traditional craft—for hunting as practised by the Inuit is an art—Kunuk the filmmaker understands the vitality of change. “Atanarjuat was timeless,” said Kunuk in an interview last year in Igloolik. “It could have happened 1,000 years ago, it could have been 500 years ago. In that time period nothing had changed, people had the same clothes, the tools were the same.” With The Journals of Knud Rasmussen, he said, “we’re moving closer to our present. The next thing to do was a real story, not a legend.”

Between 1921 and 1924, Knud Rasmussen, a Danish ethnographer of one-half Greenlandic Inuit extraction, travelled by dogsled with a variety of companions from Thule, Greenland, to Nome, Alaska. Recounted in the Report of the Fifth Thule Expedition—he had made four earlier journeys around Greenland and established a reputation as a peerless Arctic traveller—Rasmussen’s mission was to study and catalogue the life, customs, rituals, songs, and dialects of the natives he encountered. Unique among the Western explorers who travelled through these lands, Rasmussen was conversant in a Greenlandic variant of Inuktitut. Coincidentally, Nanook of the North, Robert Flaherty’s pioneering documentary set among the Inuit of northern Quebec, premiered in New York City in 1922.

True to form, Kunuk and Cohn reversed the perspective. The story is told from an Inuit point of view, through the eyes of the local inhabitants who received these curious visitors. By no means first contact—that came as early as 1576, when British explorer Martin Frobisher arrived in Baffin Island—it was nonetheless a fulcrum moment in Inuit history, when the natives were under intense pressure even from within their own ranks to abandon both their traditional lifestyle and their shamanistic belief system and adopt Western norms, particularly Christianity.

Like Atanarjuat, Rasmussen is structured around the tension between two families, each led by a rival shaman. One, Umik, cravenly embraces Christianity as a means of increasing his influence in the community; the other, Aua, rejects the notion for the simple reason that he has all the help he needs. Kunuk and Cohn make no bones about proselytizing on behalf of shamanism. In the screenplay, Aua’s spirit helpers are as real as anyone else in the story. Not that Kunuk doesn’t accept the validity of Christianity. On the contrary, he said, “Jesus was just another shaman who walked on water.”

Watching Kunuk and Cohn shoot Rasmussen, it might as well be a Zen exercise, like waiting at a seal hole. Nestled in an igloo, they shoot and they shoot and they shoot. Actors come and go through a scene but the camera whirs on. Kunuk is looking for a moment; it could be just one expression, as though hunting for the lost face of an ancestor.

From an international filmmaking perspective, the pressure is immense. If Atanarjuat represented a leap forward both in fiction and filmmaking, Rasmussen will confirm the genius of its co-creators or send them back into obscurity. But I can’t help feeling that Kunuk, the hunter who happens to be a filmmaker, will not care or even notice one way or the other. He’s been doing his thing for twenty years; a bad notice isn’t going to stop him any more than some bad weather would keep him from hunting.

On my last day visiting the Rasmussen set, I spent a few hours with Kunuk in his smoking room. I asked him if he could suggest something special I might take home to my children. He reached up to a wall shelf and brought down a brown leather satchel. Inside were a number of wolf claws. “We came across a pack,” said Kunuk. He gave me three claws, one for each boy. Later that day, I took a last look around the Igloolik Isuma office: the Caméra d’Or, surely the film world’s most prestigious prize for first films, hangs like a framed diploma on the office wall of a dentist. It’s something to be proud of but it’s not a shrine.

Outside the Toronto restaurant for an after-dinner smoke, I asked Kunuk if he’s heard any news about a sale from Cohn, his spirit helper in the white man’s world. He shook his head. He wasn’t even sure where Cohn was. “I think he’s flying back from Paris tonight,” he said, blowing smoke into Toronto’s sky. “Back home,” he added, pointing to a spot low on the horizon, “the moon would be right about there.”