The men in Sergeant Jamie Bradley’s patrol knew the drill. They had been told that there were suicide bombers in the streets of Kandahar and that the insurgents had scouted the unit. But no one in Bradley’s crew seemed visibly nervous — the risks were the same every time they rolled through the gate of the old factory where the Canadian-led Provincial Reconstruction Team is located. So machine guns were mounted, loaded, and cocked. Radios checked. A crewman opened his M203 launcher and inserted a 40 mm grenade, while the exposed turret gunners wrapped themselves in shemagh scarves to ward off the early winter wind blowing in from Afghanistan’s southern desert. As I prepared to board one of the Mercedes-built G-Wagons, equipped with nearly a ton of plated armour and bulletproof glass, Master Corporal Forbes, our mustachioed crew commander, emphasized the danger that lay ahead when he asked if I was carrying a tourniquet — one of the new ones, he explained, that can be applied one-handed if your other arm happens to be blown off in an attack.

The patrol’s destination was a police substation in the west end of Kandahar, a city jammed with vehicles of all types and sizes, including jingle trucks, whose name comes from the sound produced by the dozens of decorative chains and metal objects hanging from their bumpers. My job was to help the machine-gunner and to assist with first aid if he was hit. I also had to watch the right “arc” of the convoy for anything suspicious. The problem was, everything looked as if it could conceal a roadside bomb: propane cylinders, motorcycles, paint cans — the list was endless. “Yeah,” the driver told me, “you can get tired trying to assess every threat, so you have to filter. What is the most likely one today?”

Wrapped in grey body armour, an rcmp officer was also riding with the patrol, and when we reached the sub-station he climbed out with a C7 assault rifle and entered the building. We were clearly vulnerable. The main east-west road runs next to the station and a sniper could have been anywhere on the high ground. “There isn’t a window in that place,” explained the rcmp officer when he emerged and said that the Afghan officers inside “have two hand-held radios and use a taxi to patrol. The commander says his people bring their own weapons to work.”

Bradley then gave the signal to mount up, and a suspicious car was soon shadowing us. The patrol changed routes, but the car, which matched the model we had been told the enemy was using, stuck close to the convoy. The rear machine-gunner was prepared to shoot at the vehicle if it got too close, but it suddenly veered off. Had a suicide bomber been behind the wheel? It was unnerving being stalked in Kandahar, where escape routes are limited and narrow alleyways often lead to dead ends.

The soldiers, nearly all of them under twenty-five, knew that a few days earlier a bomb had gone off under a G-Wagon transporting an American aid representative. Three Canadian soldiers were injured and the Taliban and other insurgents — called acms, or anti-coalition militias, by the military — only retreated after they realized another Canadian patrol was operating in the area. The Canadian contingent also believed that they were embroiled in an undeclared war that could last for years — one they might not survive. “We get these letters from Canada that start with ‘Dear Peacekeeper,’ ” one soldier told me as he loaded a belt of am-munition into his machine gun. “We get annoyed with that. We’re soldiers, not peacekeepers. We’re sick of it. We are at war here.”

Prior to 9/11, if you told a Canadian commander that he would be fighting Muslim insurgents in the Afghan desert in 2006, he would have scoffed, pointed out the diminished fighting capability of our military, and maybe described Afghanistan’s bloody history. After all, while Alexander the Great managed to conquer the country in the fourth century BC, countless battles during the Middle Ages between Persians, Tartars, and Mongols settled little. Afghanistan has long since seemed to be a rootless place, an unlikely land that had the misfortune of being in the path of the spice and other trade routes and that hasn’t changed much over the centuries. It is a country some-how outside of time, a place to transition through.

Between 1839 and 1919, the British fought the armies of czarist Russia in the “Great Game” to control central Asia, and Afghanistan was repeatedly invaded and its cities ransacked. The locals held out, the imperial interlopers leaving with nothing of substance. Then, during the 1980s, Russia tried its hand again, and was defeated by the US-backed mujahedeen, a loss that contributed to the end of the Cold War and the demise of the Soviet empire. “Every stone in the Khaiber,” wrote British Lieutenant General George Moles-worth, a veteran of the Third Anglo-Afghan War (1919), “has been soaked in blood.”

Few are aware of Afghanistan’s era of relative prosperity, when, after World War II, some rich people and a growing middle class intermingled in the core cities of Kabul, the capital, and, to a lesser extent, Kandahar, where the Canadian military contingent is now stationed. But today — after the ruinous war with Russia, being abandoned by the Americans during the 1990s, and becoming the initial battlefield in the war against terrorism after the attacks on New York and Washington — Afghanistan is a devastated country with little industry and an ingrained suspicion in many quarters of foreigners. Outside of Kabul, it is governed as much by warlords peddling opium as by any constitutional authority.

So why is this beleaguered land still of strategic interest? The answer lies not in historic trade routes or future resource potential — the pipeline delivering oil from the Caspian Sea through Afghanistan’s rough terrain and rougher-still local populations seems more unlikely than ever — but in the long shadow and skewed geopolitics of a post-9/11 world. Like the countless soldiers who have gone before them, the young Canadians seem oblivious to the uncertain strategies that brought them to Afghanistan in the first place. Instead, they think only of the enemy and their own survival. “I’m ready to kill the bad guys,” said one soldier, cradling a ma-chine gun as he patrolled deep into the desert south of Kandahar. “And there are plenty of bad guys here in the hills.”

With so much attention focused on Iraq, Afghanistan has slipped under the radar, but the strategic logic behind the ongoing presence of Western forces remains: Afghanistan was the secure base area for al Qaeda, and the Taliban was its shield. Destroying the shield and ripping out the terrorist infrastructure worked, as incipient democratic institutions suggest, but there has been a counter attack, an attempt to return the country to its pre-9/11 state, and this insurgency is gaining momentum. Thus, Afghanistan is a battleground in which Western forces must be seen to be winning.

But the Americans lost nearly 100 soldiers in Afghanistan in 2005, and domestic opinion will not tolerate US troops coming home in body bags from two hostile battlegrounds for long. In January, President George Bush used the language of soft power to describe the chief goal of Operation Enduring Freedom, the American-led campaign in Afghanistan that Canada and others are currently a part of. It is “to provide stability so democracy can flourish,” said Bush. But outside of Kabul, Afghanistan appears to be descending into an anarchic hell, and democracy seems a long way off.

Even so, Canada has committed almost $1 billion for military expenditures and aid over the next three years and, as part of an aggressive US-led mission dubbed Operation Archer, was set to deploy additional troops in January, making the Canadian contingent 2,000 strong. Furthermore, this sum-mer, Canada will play a key role in the transition from American to nato command, which will allow the US to remove 2,500 of the 19,000 troops it has stationed in the Afghan theatre. Those in charge are aware that our army is now in a firefight potentially as dangerous as the Korean War, where 516 Canadian soldiers perished.

If President Bush employed temperate language and moderate hopes, Prime Minister Paul Martin warned Canadians last July that “we are at war” against terrorism in Afghanistan and that more of our soldiers could die. Soft-power advocates such as former Liberal Foreign Affairs Minister Lloyd Axworthy accept that creating stability (and delivering aid) in failed states must sometimes be done at the end of a gun barrel. But Axworthy fears that Operation Archer is actually the opening act in a dramatic shift away from traditional Canadian “peace-building” and containment policies toward confronting terrorism on the battlefield. In short, without any significant public debate, Canada has moved much closer to the post-9/11 security agenda of the United States and is now taking the fight directly to the lairs and caves of terrorists themselves. In so doing, Canada may well sacrifice the international impartiality it established by not engaging in the Iraq war and, at home, by resisting US overtures vis-a-vis continental missile defence.

Moreover, a tradition dating back to Lester Pearson, in which defence policy is used as an instrument of foreign affairs with the army sometimes used to deliver aid, seems to have been inverted. If one asks the question, “Why is sending troops to Afghanistan more important than sending them to, say, the Darfur region of Sudan, where nearly 300,000 people have died?” The obvious answer is that the United States is at war with terrorists in Afghanistan and Canada has chosen to help its ally.

Those who see a link between trade and foreign affairs believe Canada has good reason for doing so. The American security agenda extends overseas and across North America, and, as the United States consumes nearly 80 per-cent of Canadian exports and provides nearly 65 percent of our foreign direct investment, its demands for beefed-up Canadian military support, enhanced border security, and diplomatic cover can be rebuffed for only so long. According to military historian Jack Granatstein, Ottawa now realizes “that their policies will have more clout if Canada has military forces to deploy.” Added David Bercuson, director of the Centre for Military and Strategic Studies at the University of Calgary, “The Liberals got themselves between a rock and a hard place, because not going to Iraq posed the question, ‘What are you going to do?’ They clearly picked the Afghan mission as a means of sidestepping Iraq and saying, ‘Look, we are participating in the larger conflict of which you say Iraq is a part.’ ” In the entwined corridors between Defence, Foreign Affairs, and International Trade, and through shuttle diplomacy between Ottawa and Washington, the thinking may be that we will finally resolve the softwood-lumber issue and keep our border open to trade by lessening America’s burden in Afghanistan.

“The Americans were furious,” said Granatstein, commenting on Canada’s non-participation in Iraq. “[They] would have been happy with no Canadian soldiers. What they wanted was one Canadian flag.” Granatstein believes that Jean Chretien supported engagement but that, facing backbench rancour and unalloyed rejection in Quebec of the idea of sending troops to Iraq, he succumbed to the political pressure. Feeling that he had to give the US something, Chretien agreed to send troops to Afghanistan. But he misjudged how rapidly events would unfold, and since 2003 Canada’s commitment has been silently growing.

After the 2004 election, Prime Minister Martin launched foreign policy and defence reviews, the results of which included refashioning the military into an integrated force that could fight shoulder to shoulder with US troops. Bill Graham was installed as minister of Defence, Pierre Pettigrew became minister of Foreign Affairs, and, to increase the military’s profile and signal Canada’s seriousness to Washington, Rick Hillier (previously in charge of land forces) was promoted to general and chief of Defence staff.

Following 9/11, Douglas Bland, chair of Defence Management Studies at Queen’s University, wrote, “One clear message from the ‘9-11’ crisis is that trust [between Canada and the US] is greatly diminished, and now Canadians are exposed to intrusive American demands for changes to Canadian domestic politics.” The thinking goes that Canada must repair the damage done by Chretien, and make up for the lost opportunity. Not assuming real responsibility in the international war against terrorism, Bland suggested, threatens a “radical transformation” in the relationship between Canada and the United States, with the latter moving aggressively to expand its military role in North American continental security.

Though General Hillier is well liked and battle-tested from his experiences in the former Yugoslavia and Afghanistan, his promotion didn’t fit the military’s traditional pattern. According to protocol, it was the navy’s turn to supply the top gun, but the Prime Minister’s Office intervened, Martin clearly wanting someone aggressive — a warrior, not a diplomat. Thus far, Hillier hasn’t disappointed. With Martin’s support, he has announced his intent to recruit 8,000 new soldiers and rebuild the military in terms of both its prestige and effectiveness. More importantly, he created Canada Command, which will turn the military into an expeditionary force, with the infantry, navy, and air force coordinating responses to terrorist attacks, both in North America and overseas.

Hillier wants Canadians to recognize why the changes were needed: “We’re into a new era where instability and terrorists and militia forces are threats,” he said last summer. “Global instability could cause some of these things to come home to roost in Canada, and I want the population to really understand that we are asking these young men and women to die.” That is, Canadian troops are willing to make the ultimate sacrifice in wars that are in the national self-interest.

There was both a plea and a “grow up, Canada” tone to Hillier’s comments, which also seemed to disavow the old notion — espoused by Chretien in 1999 in reference to peacekeepers delivering aid to East Timor — that our armed forces are “always there, like Boy Scouts . . . Canadians love it. They think it is a nice way for Canadians to be present in the world.

“Canada’s 2005 International Policy Statement contains only a few mentions of Canadian soldiers as blue-helmeted peacekeepers operating under United Nations command. Instead, the statement suggests that the Canadian military will now be engaged in “stabilization operations” that require soldiers to wage war to advance foreign-policy goals, something they are now doing by killing insurgents in Afghanistan. The report refers to humanitarian-aid objectives by stating, “Our military could be engaged in combat against well-armed militia in one city block, stabilization operations in the next block and humanitarian relief and reconstruction two blocks over.” In Afghanistan, aid will be delivered in order to win support for the fledgling government of Hamid Karzai.

Are Canadians prepared to accept a wider role for the military — one that includes sending soldiers abroad to fight and be killed? While Conservative Leader Stephen Harper promised $17 billion for the armed forces over the next five years and an elite airborne battalion of 650 soldiers, judging by the winter election debates, the answer is decidedly no. Over four debates in both official languages, not once was the issue of Canada’s entry into Afghanistan and engagement with the war on terrorism seriously raised. One was left to wonder whether Canada has become a myopic, even parochial, state that is not ready to engage in the fight against international terrorism.

The irony of this situation is that the icon of Canadian peacekeeping, Pearson, actually countenanced peacemaking and the use of force when necessary. He did not insist that the army was best suited to delivering aid rather than firing bullets. After winning the Nobel Peace Prize for helping resolve the Suez crisis in 1956, Pearson, who later became prime minister, engaged in a bitter dispute with Washington over defence. He wanted to create an expeditionary force similar to the one currently fighting in Afghanistan, believing that many foreign conflicts — often steeped in ancestral and/or ethnic claims of entitlement — required more than negoti-ations and foreign aid to solve. In short, he wanted to create a rapid-reaction “stability” force that could be deployed to wage war if it meant a lasting peace could be achieved.

Under Pearson, the military made plans to purchase a squadron of transport jets with global reach, as well as ships that would carry the revolutionary tilt-winged aircraft. When Trudeau replaced Pearson as prime minister in 1968, he halted these initiatives. In the ensuing years, Canada’s military declined from nearly 100,000 troops to less than 60,000 today. The Vietnam fiasco and the easy political play of distancing Canada from US militarism changed the attitudes of Canadians, who increasingly embraced the idea that their soldiers were peacekeepers. It helped that peacekeeping was cheaper, since it didn’t require the government to constantly update the military’s arsenal or replace worn-out equipment, such as the critically important Hercules aircraft.

In a prophetic warning just prior to 9/11, Gordon Giffin, then the US ambassador to Canada, said: “If [Canada’s] defence relationship erodes in a meaningful way, it could affect the fabric of the whole relationship.” And since 9/11, politicians on both sides of the House of Commons have supported rebuilding the military along the lines that Pearson long ago envisioned and the White House now wants. Estimates for such an upgrade begin at $30 billion.

The mission in Afghanistan is the first example of what a more robust Canadian military can do. After a long period in which our overseas war fighting capacity was confined primarily to bases in Europe — where 10,000 soldiers trained, many in tanks or in planes with nuclear-tipped weapons, to fight in an anticipated third world war as part of nato — Canada is now engaged in a counter-insurgency campaign that brings all the elements of the country’s power to bear: military force, diplomacy, economic power, and development assistance. The experience will illustrate how Canada might be involved in the war on terrorism in the future.

One unique aspect of the new strategy is the way that development and humanitarian aid are being used specifically for the purpose of building loyalty toward coalition forces and democratic reforms. The American, British, and Canadian governments all have representatives from their international development and relief agencies stationed in Afghanistan; the Canadian International Development Agency (cida) alone plans to spend $616 million there by 2009. But the responsibility for taking aid workers into and out of remote areas falls to the patrol company, which is part of the Canadian-led Provincial Reconstruction Team (prt) in Kandahar, where Sergeant Bradley and nearly 200 other soldiers are based.

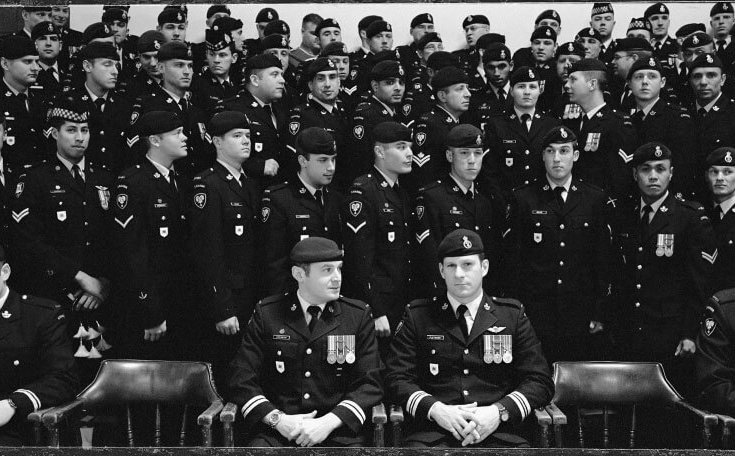

Unlike traditional Canadian peace-keeping units, which would deliver aid but not engage either side of the conflict, prts, in what could be a model for future expeditionary forces, are front-line fighting units. Most of the soldiers come from 3rd Battalion, Princess Patricia’s Canadian Light Infantry, based in Edmonton, and many do not want their names used in print, fearing the enemy has ties to jihadist groups, including al Qaeda and its supporters in Canada. “We are targets and they want to kill us to stop our work,” said a US aid representative whose convoy was attacked later in the week. “They will do anything to stop us helping the Afghan people.”

Soldiers and aid workers make these dangerous trips to remote areas to assist populations terrorized by insurgents not only to get help there, but as a show of force. “The war will be won in the hinterland, with the people,” said Colonel Steven Bowes, the prt commander. “The enemy uses these areas as sanctuaries, and conventional military operations can only succeed up to a point. Projects that improve the basic living standard are a start, but we are not into development for development’s sake.”

The Afghan government will eventually have to fill the void. But as a source at the Afghan Ministry of Interior pointed out, until “our security institutions are rebuilt the country will have to depend on the West.” As the insurgency becomes bolder, there is both a race against time and a recognition that this could be a long and protracted war. Does this mean years of suicide bombing directed against Canadian soldiers?

On January 16, Taliban insurgents assassinated Glyn Berry, a senior Foreign Affairs official and head of the prt. The insurgents drove a car laden with explosives into a Canadian convoy of G-Wagons in which Berry was riding. Three Canadian soldiers were also injured in the attack, two critically. Such attacks, military analysts say, may be the first stage of a last-ditch effort. “Our enemy is losing the fight and they resort to suicide attacks that kill more Afghans than coalition forces,” says one top Canadian military official. “The Afghan people, based on our latest information, resent the [insurgents] not the coalition forces.”

In December, I joined a long-range Canadian patrol on its way to the remote Maruf district of Kandahar Province. The troops were armed to the teeth, as the route is well-travelled by insurgents entering from Pakistan. There were no real roads so the patrol drove through wet and dry wadis (ditches) to reach this vital district. The situation could go either way here. Insurgents control the rough, hilly area we moved through and regularly terrorize the local villagers into providing food and information. The patrol reached a forward operating base staffed by French special forces. Their job at this location, which reminded me of the terrain described in the book Beau Geste, was to track down and kill the elusive insurgents who intermittently attack the base. “They tried to rocket us the other night,” the commander told me. “We have systems that can track and kill them at night — and we do just that.”

The loyalty of the people in the valleys was split. Half wanted nothing to do with the insurgents while the others supported them — but only, the unit believed, because they were being coerced. That is where the prt came in. Regular visits by aid-agency representatives, as well as small but important construction projects such as water-diversion schemes (vital to the drought-wracked region), not only improved the lives of local people but made them much more likely to assist coalition forces. The prt included two rcmp officers, whose job was to help establish effective policing in Kandahar Province. “With increased security, which includes the elimination of the [insurgents],” one aid-agency representative explained, “we will eventually be able to push development in here. But not yet.”

At one point, we approached an impoverished village. It consisted of a series of walled compounds interspersed with terraced fields for small crops. The village elders welcomed us into their fastidiously clean mud houses. Reclining on mats and cushions, the soldiers asked what assistance could be provided. “Better irrigation control,” was one answer. The village needed a small dam to divert water to the crops. When we asked about security, the men became reticent. It later emerged that local police had been collecting an illegal tax.

The strategic use of aid may offend some, but this approach is gaining credibility and has been adopted by cida and Foreign Affairs. This was not the case back in 2002, when cida field representatives were unwilling to support a battle group from the Princess Patricia’s Canadian Light Infantry that had arrived in Kandahar shortly after Afghanistan was invaded by Western forces. cida officials claimed the soldiers were engaged in war, not peacekeeping; in the end, the regiment had to spend $40,000 of its own money to drill wells and refurbish schools. But cida is now working closely with the military.

By combining aid and military power, and by assuming a bigger role in Afghanistan, Ottawa also hopes to avoid repeating one of the harsh lessons of the Bosnian conflict. Even though the army spent years in Bosnia and Kosovo, when it came to decision-making Ottawa had very little say because the Canadian presence wasn’t large enough. “You never got credit for it because it was a small contribution, relatively speaking, not enough to be above the radar,” says Hillier. “So we never got a seat at the leadership table and we never got a chance to influence places like Croatia, Bosnia, and Kosovo in accordance with Canadian values and in accordance with our interest.”

On this point, Lloyd Axworthy and Hillier could not be further apart. Ax-worthy believes that under Martin there has been a clear break between the military and Foreign Affairs, and that Canadian defence policy is falling in line with US foreign-policy goals. “I don’t think Foreign Affairs acts as the source any longer for the peace-building approach,” said Axworthy. “Prime Minister Martin has bought into the kind of approach that says you have to flex your muscles to show that you are smart or effective. But I think we had a pretty effective foreign policy without going around and beating up people.”

Axworthy believes the armed forces should be peacekeepers first and should be equipped to respond rapidly to emergencies around the world. He would use diplomacy and aid to solve disputes, but not necessarily involve troops in combat. “When I was in Foreign Affairs,” said Axworthy, “I always argued for effective armed forces, but not, as our present chief of staff says, to ‘go out and kill people.’ ” As a result of Canada’s more aggressive posture, he said, we have ended up with troops in Afghanistan but not in Darfur. “There, I think, is the nub. Do we simply want to be part of this US-led counter-force strategy or do we want to provide the ability for people to go in and save lives rather than take lives?”

To counter the current trend toward a more interventionist military, he believes Foreign Affairs needs to develop a wider peacekeeping strategy, one grounded in the delivery of humanitarian assistance. “Look at what we learned in the past year,” he said. “There were far more lives taken by the tsunami and by earthquakes [than war].” He also doubts that Canada’s approach to fighting terrorism in Afghanistan will effect real change. Noting that the country is the world’s largest supplier of heroin, Axworthy asked: “If you have all sorts of warlords making money off of heroin, what are our 2,000 people doing there? Isn’t the whole question of controlling drug trafficking and the money that flows to criminals and terrorists a much more serious issue than chasing the Taliban back into the hills?”

With the shift in focus in Ottawa, and with so many military resources now tied up in Afghanistan, it is unlikely that Axworthy’s views on peace-building will resonate anytime soon. As of January 2006, Defence Minister Bill Graham had avoided speculating on how long we would be in Afghanistan, but Jack Granatstein believes that Canadians could be there for decades.

In the end, public opinion, which has yet to truly engage the Afghanistan question, may decide how long the army stays in that country and whether the rebuilding of the armed forces should continue. Polls consistently show that Canadians, perhaps because they have basked under the US security umbrella for so long, would quickly cut spending on the military if the money was shifted to health care. It is also unclear how Canadians would deal with a steady flow of dead soldiers coming home from Afghanistan. If that happens, Michael Adams, author of American Backlash, said that growing differences between the United States and Canada could surface if the public decides that Canadian troops have become mere foot soldiers in America’s “war on terror.” Canadians, he said, are far less militaristic than Americans and stand to the left of their US counterparts on most major issues. “The question is whether Canada will have the political will to stay in,” said Granatstein. “And that will depend on casualties and politics. But certainly the military is thinking they are in for a long haul.”

Darkness has fallen over the Canadian base in Kandahar, and the Muslim call to prayer echoes from minarets across the city. As the Allah hu Akbar chant fades, a Canadian soldier climbs to the top of a wall. He plays “Scotland the Brave” on his bagpipes, the mournful strains of the Highlands sounding eerily out of place in the desert. It leaves some soldiers homesick for friends and family thousands of kilometres away and makes all of them aware of the military family they have in Afghanistan. “This is the finest unit of men and women I have worked with — ever,” said Regimental Sergeant Major Ward Brown, a twenty-six-year veteran. “They put it on the line every day. Canadians should know we are at war here and their best are engaged in the fight.”