In ad 1271, Marco Polo travelled to the farthest reaches of Asia and discovered the origins of what had become the linchpin of European social order: spice. Spice ruled the ancient world. Empires rose and fell, religions began and thrived, wars were fought, and fortunes made, all driven by the engine of flavour. Food back then was neither good nor particularly palatable. Medieval man preserved his meat with salt and then cooked it until thoroughly charred. Spice delivered a gastronomic orgy reserved only for the wealthy and the powerful. A pound of ginger would cost you a sheep. Pepper was worth more than gold. Arab traders sold it peppercorn by peppercorn.

Today, the spice trade continues to flourish, but not just in the common and inexpensive herbs and botanicals you find dried on your grocer’s shelves. The substances now more valuable than gold are the biochemical molecules of flavour themselves. Without the potent chemicals carefully designed by the flavour industry, processed food—i.e., food that has been prepared, frozen, canned, extruded, bottled, jarred, dried, or vacuum-packed—would be essentially inedible. About 90 percent of what Americans spend on food goes to buying processed food.

The world market for manufactured flavours is about $8 billion (US) per year. You see them in those cryptic phrases listed on most packaged-food labels: natural flavour or artificial flavour. The typical American eats one out of four meals in restaurants, including fast-food restaurants, and most fast food is dosed with flavourings. Even so-called “white tablecloth” eateries commonly employ sauces, dressings, stocks, and beverages that include flavouring. Two-thirds of the remainder of the American diet consists of processed food, and most of it contains added flavour.

The flavour industry spans the earth, shaping the human palate and, by extension, global culture itself. What we taste, often, is the strange alchemy of a group of specialists who inhabit a parallel world, a place where food is abstract, where strawberry is a relative concept. Food tastes the way it does because a flavour scientist spent weeks combining molecules to make it so.

So when Givaudan, the world’s largest flavour and fragrance manufacturer, invited me to travel with them to China on a TasteTrek, sniffing around for new flavours and ingredients that might prove useful in their global efforts to colonize the human tongue, I packed my bags. If we are what we eat, what are we when what we consume is a simulacrum, a caricature of food, created in a Cincinnati lab?

Shanghai: Pearl of the Orient, whore of Asia. China: Land of mystery and intrigue, the inscrutable east.

Nonsense.

Judging from the massive redevelopment project that is modern Shanghai, China is actively wiping away five millennia of culture and tradition in one sweep of the bulldozer. Construction cranes fill the horizon like wheat in a Saskatchewan field. At last report, Shanghai alone had over 300 high-rise buildings under construction.

My hotel sits on the bank of the Huangpu River opposite Shanghai proper, in Pudong. Fifteen years ago, Pudong was a bunch of rice paddies. Then Beijing decided that it should become one of the financial centres of Asia, so, like a theme hotel in Las Vegas, they invented a city. And it is just as surreal. Gleaming glass towers, thirty to ninety storeys tall, shimmer in the late-setting sunlight. Most sport futurist designs seemingly created by architects overdosed on 1950s sci-fi flicks and episodes of The Jetsons. The Oriental Pearl TV Tower, at 468 metres the tallest tower in Asia, looks like three Styrofoam balls stuck on a metal music stand.

As widely reported, the New China boom has transformed 1.3 billion people into a supercharged mass of industry and enterprise propelled by the fear that it could all end tomorrow. Walking through Shanghai, it struck me as a culture hooked on cocaine; everyone is dancing as fast as he or she can, living intensely for the moment, unaware of where it will lead.

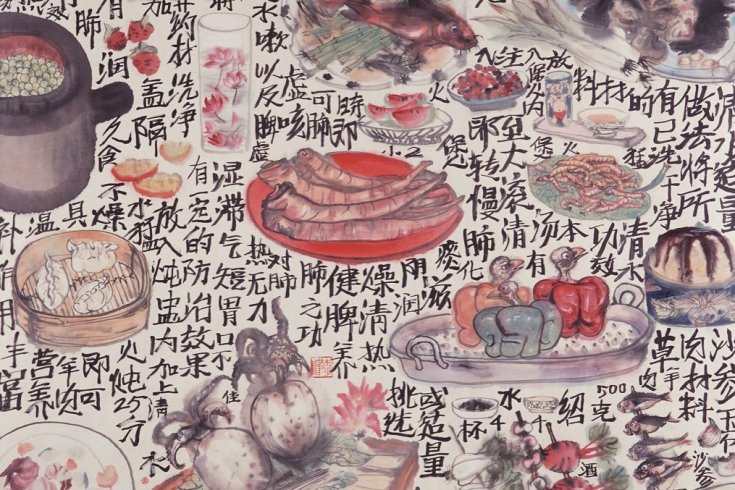

I buy a sizzling lamb kebab, redolent with cumin and hot pepper, from the charcoal brazier of a tattered Uygur street vendor sitting at the entrance to a new subway station. About the only thing left in China that clings to a shred of authenticity is the food. Chinese cuisine flows from a 5,000-year tradition that blends sustenance, medicine, religion, social order, and philosophy. China, I realize, is the perfect backdrop against which to explore how the genuine is transformed into the artificial.

Four days after landing, I meet Jeff Peppet, Givaudan’s global director of marketing communications, and Willi Grab, director of flavour science, at 1221, one of the hip new Western-style eateries that have sprung up in Shanghai. It was Jeff’s infectious, gee-whiz enthusiasm that hooked me on the idea that flavours have something to say about world culture. Willi, a calm Swiss-German with a gentle smile, is based in Singapore and has been chasing flavours for thirty-six years.

Moments after we sit down, the waiter fills our teacups with a mix of green tea leaves, small dried fruits, and scalding hot water. Willi lifts his cup like a sommelier. He sniffs it carefully. “It smells like vettaye,” he says. I don’t quite understand him. “You’re not from the country,” he says, and then repeats more slowly, “vet hay.” I sip my tea. Astonishingly, it tastes exactly as might a field of newly mown hay in the morning dew—grassyu and slightly bitter.

They do the ordering. When the dishes arrive, I dig into something called “spicy beef,” slices of tender sirloin in a rich brown sauce. It’s served with a small round loaf of sesame-seed-coated, scallion-flavoured bread. Willi gingerly smells the bread. “Whoa!” he says, recoiling as if something bit him. His pale eyes twinkle with delight. Jeff smells it too. “Amazing,” he says. I taste the bread. It tastes like . . . bread. Good bread, oniony bread, but bread. I’m starting to sense that my companions are experiencing the meal quite differently than from me. So I ask Willi to describe the dish I’m eating. Suddenly serious, he furrows his brow, chopsticks a piece of meat, and sniffs. “It has a natural beef flavour,” he says, “not a beef that’s planned.” Then he describes something he calls “the pepper note,” which he says features a Szechuan pepper called hua jiao, unusual for its effervescent quality. “Like when you put the tip of a battery in your mouth,” he says. “We say it’s cold, hot, not cold, and not hot, all at the same time.”

As we talk, the world of food science begins to open its doors to me. Taste, Willi explains, holds many properties that make it unique in the pentarchy of the senses, but subtlety is not one of them. Your mouth contains but five types of chemo-sensory receptors that are capable of bluntly discerning just five gustatory qualities: sweet, sour, bitter, salty, and something called umami, which loosely translates from Japanese as “deliciousness.” ( It’s the “mouth feel” you get from mushrooms or beef. Umami has no flavour of its own; it simply makes other flavours taste better.) Your mouth also senses pain, called trigeminal perception, which allows you to discern the hot in chili pepper and the cool in menthol.

On the other hand, the 340-odd chemo-sensory receptors in your nose can distinguish an enormous range of odours. When you eat, you smell your food twice; once through your nose as it approaches your mouth (orthonasal perception) and again during consumption as the odour ascends the back of your throat (retronasal perception). Your brain combines this complex scent information with basic taste sensations and trigeminal perception to create what you identify as a food’s flavour.

Though a science, flavour creation is to some degree a literary conceit. To understand it, you must learn to speak it trippingly on your tongue. Every act of tasting has syntax, a succession of distinct flavour sensations that unfold through time. For flavourists, each expresses itself like a well-constructed line of poetry, a series of metaphoric descriptors that attempt to limn the playful dance of experience happening in their mouths. When you eat a strawberry, you don’t apprehend strawberry, you experience a series of stimulations from sweet to sour to lemony to green to hay to sweet, green, sweet, sour, and so on. These are called flavour notes.

Flavour creators often employ the language of music to describe their work. They speak of the top, middle, and bottom notes, of overtones and undertones, of dominants, sustain, and the way a note “comes in.” They also borrow freely from the language of visual art, describing certain experiences as being in the foreground while others recede. They refer to a flavour’s point of focus, its dominant colour, the vibrancy, and the impression it leaves.

Descriptors such as “brothy,” “citral,” “horsey,” and “green” dot the flavour industry’s vocabulary. Within these highly specialized terms there are finer shadings: the green of fresh-cut grass, the green of citrus, or the green of new tomatoes, for example. This vocabulary references a set of training experiences that flavourists undergo to attune themselves to known standards. Hence, Willi’s description of the tea: if you had asked me, I’d have said “green tea,” but to Willi it was wet hay, and he was precisely correct.

Embracing the descriptive language of flavourists forever changes the way you perceive food. No longer are you able to say “what a great pizza” or “delicious pie.” In fact, no longer are you able to conceive of pie as “pie.” Instead, each mouthful presents a postmodern collage of individual stimulations, as distinct from one another as the brush strokes of a Monet or the words of a sentence. The syntax of sensation plays itself out in your consciousness, and your mind assembles its meaning.

As we taxi back to the hotel, I begin to see why flavour creation is as much art as science, for what is art but an attempt to render the essence of human experience in a highly structured—some might say artificial—form?

Wuhan, at the confluence of the Han and Yangtze rivers, is one of China’s Three Cauldrons, so named for its oppressive summer heat. As we deplane, the air hits us in the face like a barber’s wet towel. Historically a trading city at the centre of a hardscrabble region, Wuhan fell into industrial disrepair during the Maoist era. Now, the pace of construction is no less furious than in Shanghai as Wuhan, too, makes itself new. The growl of heavy machinery drowns out everything but the snarling traffic.

The next morning, our TasteTrek officially begins. They split us into two teams of roughly ten members each. I join Jeff on team one, which is anchored by chief scientist Xiaogen (pronounced sho-gun) Yang. A precise and contained man, Xiaogen’s team of flavourists and product designers hail mostly from Cincinnati, where Givaudan maintains its world headquarters for R&D. Willi leads team two, with similar staff from Singapore, including lead flavourist Lee Hiang Phoon, one of the first Asian women trained in the discipline.

At the behest of a client who wishes to create a line of authentically flavoured dehydrated noodles, this China trip will be focused on sampling specific dishes. Givaudan’s previous treks explored places like Madagascar, Mexico, and the rainforests of Gabon, in West Africa. In Gabon, they employed the world’s largest hot-air balloon to fly over the jungle canopy so they could sample organics from the treetops. There, they discovered five previously unknown species of fruits and plants. Today, team one will try to capture the “headspace” of a dish called payulian. In food science terms, headspace is the totality of the aroma molecules given off by anything—a fruit, a flower, or, in this case, an entire dish. Headspace analysis represents a quantum leap forward in the science of flavour creation. This will be our central task at the many restaurants we visit over the next week.

Payulian roughly translates as “spreadface fish.” The head of a spotted silver carp is boiled in two different soups, split open bottom to top, laid flat on a plate, and adorned with a sauce made of cherries, chives, sweet red peppers, and scallions. There is no meat per se, just fish lips and fish brains. “Quickly taste lip,” our daily schedule instructs us, in charmingly broken English, “but slowly taste fish head, then you will find the flavour is excellent and must be your favourite.”

At the Wuhan Fu Yee Hotel, where payulian was invented, they usher our team into a private dining room dominated by a traditional large, round table, Lazy Susan at its centre. Within minutes, the payulian arrives, glistening on the plate in its cherry brown sauce, surrounded by tortilla-chip-sized wedges of a crisp flatbread, and garnished with a purple orchid. Its lush aroma fills every corner of the room. The food scientists stare. Then they whip out their cameras and start taking pictures. Then they sniff, then poke, then prod, then discuss. Spiral pads appear. Notes are scribbled furiously. More sniffing. More talk. Forty-five minutes go by without anyone tasting the fish.

During this process, Xiaogen produces what looks like a clear glass soup bowl turned upside-down, with glass straws sticking up out of it. Called an “aroma chamber,” it’s similar to others he’s had made in a variety of sizes for different applications. This twenty-centimetre round version is specifically designed for prepared dishes. He positions the chamber over various parts of the fish, trying to isolate unique odours. The milling crowd takes turns sniffing the glass straws to determine what yields the fullest aroma.

Finally, Xiaogen removes the dome and the others start tasting. Science aside, they must create a personal sense-memory of the dish so as to better duplicate it in the lab.

While they do, Xiaogen constructs his sampling rig. He screws hand-blown glass tubes into the nipples protruding from the bell jar and attaches hoses to each. The hoses, in turn, connect to little vacuum pumps called “flow metres.” To capture the aroma, the pumps will draw a calibrated amount of air through small, glass-enclosed filters, called “traps,” no more than a few centimetres long and millimetres thin. Like the filter on a cigarette, each trap contains inert synthetic polymer fibres capable of capturing aroma molecules.

When flavourists design food products, they think in terms of a tripartite pyramid divided from bottom to top representing the bass, middle, and top notes. The bass note is the blunt, sweet/salty/sour/bitter/umami sensation in the mouth, and the middle note is the signature flavour, like chicken for example, that generally defines a dish. These notes are the preserve of product designers and chefs whose job it is to duplicate the basic ingredients a manufacturer intends to use in a product. The top note is the aroma, the note that gives a dish its complexity, variety, and unique qualities. Aroma is the great differentiator. This is the realm of flavourists, the alchemical realm in which molecules and ingredients are selected for the ephemeral sensation a consumer will experience when the food transforms in his or her mouth. This is what a packaged-food label is talking about when it uses the word “flavouring.” Headspace analysis attempts to capture the aroma released by the target food, be it a prepared dish like payulian, a fruit on the tree, or a handful of black pepper.

A dish’s aroma, like its taste experience, is dynamic. It begins at point A and degrades over time with a speed unique to each dish. From a food designer’s perspective, the optimum aroma—the one that will make the product a hit with consumers—lies within a segment of that temporal arc. That’s why McDonald’s hamburgers only sit in their warmer for a predetermined period. After that, the burgers might satisfy hunger, but their aroma is gone, and with it their taste. Xiaogen’s sampling process averages the aroma experience over a period of optimum desirability. Payulian, it turns out, smells great for about thirty minutes and then starts to smell like, well, old fish. So fresh dishes of payulian speed from the kitchen every half hour for the rest of the day.

As recently as a few years ago, flavour creation was an analog art form. If a client wanted a payulian dried-noodle product, Givaudan would have sent a flavourist to smell and taste the dish, then, using various known flavour molecules, make a fishy/cherry-ish product and call it Payulian™. Xiaogen will subject the sample we collect today to gas chromatography mass spectrum analysis and produce a far more complete road map of its constituent molecules. Such equipment won’t replace the flavourist—the human tongue remains the final arbiter of successful food product design—but this headspace process allows for the design of flavourings with far greater verisimilitude than those previously attainable by designers alone.

Xiaogen begins his sampling and . . . nothing much happens. Let’s face it, science is slow. Watching air being drawn through a tube is somewhat less exciting than waiting for water to boil. So after a couple of hours, Jeff and I slip out to brave the liquid heat on a walking trip to the nearby wholesale fish market.

Food people salivate at the prospect of visiting local markets. Each journey holds the promise of undiscovered wisdom, transcendence in the form of strange dried reptiles, obscure botanicals, or local ingredients that have never seen the light of a wok outside Wuhan. At the first market we visit—a couple of long, cinder-block buildings with tile-paved corridors running widthwise through them—small stalls line each aisle, most run by families specializing in local seafood. In one stall, bins of medium-size turtles extend their odd necks from their green-brown shells. In another, a young couple sits washing a twisted clump of several hundred shiny freshwater eels writhing in a laundry basket. Jeff gets particularly excited at a stall whose walls are lined with jugs of marinated mushrooms in every hue and shade. Fresh fungi, in indescribable variety and profusion, fill open tubs in its centre. The heady odour hits me like hashish, and I suddenly understand the concept of umami, that rich sensation that fills your mouth like a warm, thick broth.

“Over the last fifteen years, we’ve had an explosion in the availability of ingredients,” Jeff says as we stroll on. “We’re now able to get fruits and vegetables all year round with no seasonal issues. New foods from around the world are commonly available on supermarket shelves in places like Cincinnati. Even our best chefs feel they can get ingredients in the US as good as those from the countries where they came from.”

“Still,” he adds, “the average American eats like shit.”

We pass a man selling fish skin by the kilo. Not only do Americans eat badly, Jeff argues, but they are, as a culture, tremendously resistant to culinary change. He points to the soft-drink manufacturing industry, long aggressive when it comes to “the next new thing.” “But what got launched last year?” he asks rhetorically. “Lemon and vanilla. There just isn’t a desire in the market for complexity.”

We leave the market and walk out on the boiling streets. Jeff sounds alternately like a frustrated gourmand and a pragmatic marketing man.

“On our first TasteTrek, to the jungle of western Gabon, we came back with maybe a dozen great new flavours, mostly tropical fruit, each with something unidentifiable in them. When we demo’ed them, the product development people found them ‘interesting.’ They know that if you don’t put them together with something simple and familiar, like strawberry, the American public just won’t buy it.”

Givaudan manufactures over 6,000 flavours called strawberry. That’s right: 6,000. And they continue to make new ones. “The strawberry you pick in Provence is totally different than the one cultivated in California,” Jeff says. “If you take a strawberry-flavoured taffy, it’s nothing like a strawberry sorbet, and nothing like the strawberry you pick fresh in the field.”

And of all those thousands of strawberry flavours that end up in gums and sodas and yogourts and candies and ice creams, why do so few actually taste like a strawberry?

“That’s why we keep making more of them,” he replies.

In reality, strawberry Jell-O is not trying to taste like a fresh strawberry. It wants to be Strawberry Jell-O™, a branded, identifiable flavour that may bear little relation to nature. That’s why Givaudan also makes 4,000 varieties of orange, 3,000 different flavours called chicken, 5,000 individual beefs, and a few thousand butter flavours. And that’s just for the North American market. Asia and Europe have thousands more of each, specific to their culinary preferences.

Yet despite the tendency of US consumers to gravitate toward the known, adventures in the flavour trade do expand the American palate. Latin American cuisine is a good example. The huge increase in first-generation Hispanics created a niche the processed- food industry quickly moved to serve by duplicating the traditional cooking to which these consumers were accustomed. As Latin American food penetrated the consciousness of non-Hispanic Americans, processed products featuring these tastes flooded the supermarket shelves. Most resembled dumbed-down versions of the spicy and distinct originals. As a culture, America has an almost infinitely elastic ability to co-opt and commodify resistance. It doesn’t reject the new and different, as China does, it recontextualizes them, converting them into pale imitations of themselves.

I ask Jeff about the rest of the world. “In flavour profiles, the Asian and South American markets seem to be looking for authenticity,” he said, “but that is changing.” He points to Kentucky Fried Chicken’s phenomenal success in China. “The Chinese want to see how Americans eat, whether or not they can afford it. Now, if kfc becomes the restaurant meal of choice, rather than an occasional treat, it’s more possible that a packaged food with American flavour profiles and taste components will be successful here.”

When we return to the hotel, Xiaogen’s work nears completion. He has flushed the contents of his microfibre traps with an odourless, tasteless solvent called “hexane,” and now syringes the clear liquid onto a slip of absorbent paper, passing it around the room. Everyone sniffs and nods, big smiles on their faces. We have a winner.

“Peppery,” says someone. “Fermented like soy sauce,” says another. Others suggest it is oniony, caramelized, and like fried doughnuts. When the strip gets to me I sniff gingerly. The aroma is astounding, a full evocation of the richness and densely layered experience of payulian. If I close my eyes I can see the steaming fish glistening before me.

And yet . . . I sense something else, too, a certain plasticity, an acrid artificiality that I can’t deny. Perhaps this is a trick of mind, a function of the sample’s abstraction from anything recognizable as food. I ask Xiaogen about this. His face immediately lights up in a startled smile. “You are very sensitive,” he says. “You are smelling the hexane solvent. Most people can’t perceive it.”

We go through life thinking that we smell and taste what others do, that we all share a common sensory experience of the world. But it’s not true. Taste and smell are highly subjective, and the range of sensitivity that doctors consider normal is wide. Age, gender, race, genetics, and other factors all play roles. In hexane, I smell something that exists far below the sense threshold of most people. I learn, in a flash, that I have a great nose.

“Look there,” says my native-born photographer Kevin Lee, pointing to a sign in a shop window. It is three days later, and we are boarding a bus that will take us from our hotel in Shenyang to today’s restaurant. After a blur of samples from blood sausage to stewed pigeon soup, I’ve joined Willi on team two to test a renowned hot pot made only in this remote northern city. I look where Kevin points to see a small ma-and-pa type restaurant: a few cheap tables and a Formica counter, a middle-aged couple eating from bowls of brownish stew. Kevin points to a sign in the window and translates it as “fresh dog daily.”

Shenyang, situated just 130 kilometres from the North Korean border, is known throughout China as the “City of Dog.” It clings alternately to its Maoist past and its love of a labrador lunch. (Even within the world of canine consumption, gourmands differentiate. Black dog is considered much more desirable than white.) In the town centre, we drive past a ten-metre-high statue of the Great Leader urging the peasants and workers forward into a glorious socialist-realism future that never was.

At the Guo Fu Fei Niu restaurant, they seat us in front of a pot of soup boiling over an individual burner. Cooking a hot pot is a personal art. You add beef, vegetables, and sauces to taste, cooking each bite as you eat. Arrayed on our table are plates of exquisite mushrooms (three or four different varieties), beef marrow, coriander, fish balls, and the main reason we came here, fat beef. Fat beef is thinly sliced rib-eye steak processed with a proprietary technique that transforms the lactic acid built up during slaughter into glutamic acid, the main ingredient in monosodium glutamate, msg. Glutamic acid occurs naturally in food and accounts for umami. The beef on these plates is, without question, the most tender, most flavourful I’ve ever had.

As we gorge ourselves, Willi walks around the table, periodically sampling each person’s broth to find one closest to the client’s target. An hour later, he has set up his rig over two pots and is busily sampling. Though a highly accomplished scientist in his own right, Willi is old school. His scientific equipment consists of two silver architect’s lamps with their sockets removed and a bunch of rubber tubes jammed into the rear vent holes.

While the flow metres suck air through Willi’s traps, I ask flavourist Lee Hiang Phoon just how precise this process needs to be in order to succeed. “This soup’s aroma might have thousands of molecules in it,” she says. “I’m going to recreate that flavour with maybe thirty-five or forty ingredients. Still, we need as much information as possible to know which notes are most impactful.”

Why so few?

“Flavouring is an abstraction, just the aroma and the retronasal impression of the dish. An aroma can remind you of things, but it’s not a photograph. What I’m trying to do is give you a reflection, a caricature at best.”

She asks me if I know why food manufacturers use flavours in the first place. I have always assumed that the extremes of heat, pressure, and stress inflicted on food during the manufacturing process destroyed what flavour there was. “Partially true,” she tells me. “But they use flavour precisely because they don’t want to use too many natural ingredients. If you put twenty tomatoes in a bottle of spaghetti sauce, you’ll get good flavour, but the cost will be high. If you reduce the amount of natural things and put in flavour, it becomes cost-effective.”

Is it cheaper to manufacture all the chemicals, starches, emulsifiers, msg, salt, and flavours that replace the tomatoes than to use tomatoes themselves?

“Yes,” she says, “a flavour not only substitutes for ingredients, but also for cooking processes. Rather than adding ten different spices and meats and slow cooking it for six hours, you can add a flavour compound that contains all that, including the slow-cook flavour. This speeds up production.”

“Plus,” she adds, “flavours are very concentrated. Spaghetti sauce typically contains less than 1 percent flavour.”

That’s why flavouring appears nearly last on most labels. The amount required to almost completely flavour a product is minuscule. A 355-millilitre can of cola, for example, contains just one-fifth-of-one-percent flavour, about two-thirds of one millilitre. The rest is sugar water.

Jeff has been listening in on our conversation. “From a consumer-acceptance standpoint,” he interjects, “labels are what processed food is all about.” The life of a processed-food product begins with a descriptive brief, usually created by a client’s marketing department. The brief outlines the general nature of the product, the demographic of its intended consumers, and, most critically, its labelling requirements.

The most significant trend in food manufacturing over the last twenty years has been the development of products that can be labelled “all natural.” The typical consumer believes that naturally flavoured processed food is somehow healthier than artificially flavoured processed food. The distinction is laughable. “Flavours are value-neutral from a health standpoint,” says Jeff. “They are chemicals. The only difference between a natural and synthetic flavour is the source material and derivation process.”

Take cherry, for example. What gives cherries their “cherriness” is a molecule called benzaldehyde. To make natural cherry flavour, you start with cassia, a tree bark related to cinnamon and, using chemical-free processes like pressure and steam, extract from it cinnamic aldehyde. This can then be converted into benzaldehyde, the base of natural cherry flavour. To make an artificial cherry flavour, you extract the benzaldehyde from coal tar or petroleum using chemical processes. The molecules resulting from both processes are identical, although the natural flavour costs ten to fifty times more to produce.

Aside from flavour, the other ingredients in “all natural” foods—starches, proteins, fats, etc.—are often dramatically modified from their naturally occurring states in order to produce products that better withstand the intense processing required to manufacture safe packaged food. “All-natural processed food is an oxymoron and a myth,” says Jeff. “But the idea that it’s better for you is deeply ingrained in society. It’s become a key to success from a consumer-acceptance standpoint.”

Food preference is driven by lifestyle, and, with wealth, people want to eat better, to eat leaner and healthier. Of course when we talk about Americans, we’re talking about leaner and healthier canned foods, and frozen foods, and dried, extruded, reconstituted foods. Foods that are easy and convenient. So people read about new international cuisines, new flavours, new Food Channel dishes and want them, but only badly enough to pop them in their microwave or add hot water. Better living through chemistry. And now the whole world wants it.

That night, I meet with Lee Hiang, the flavourist from team two, in our hotel lobby. She’s a petite woman with short black hair, and a wide, ready smile. Flavour is a man’s world, born from the same culinary traditions that gave us generations of male chefs. Lee Hiang’s status as one of the first Asian women so trained gives her a unique perspective towards her craft.

“Eating is pleasure,” she says. “In traditional Chinese culture, cooking is an art. There are different kinds of braising, slow cooking, and different ingredients like suet and whey. All require special cooking procedures.”

She elaborates on the Chinese philosophy of food, how all meals are conceived with the Taoist balance in mind, the yin and the yang of the food mirroring the spiritual balance of the consumer. Achieving that culinary rigour isn’t easy. “The soup we sampled yesterday would traditionally be made by the daughter-in-law to balance the ‘heatiness’ of another dish,” she says. “Heatiness is a yang concept, so this soup would provide the yin balance. But to make it, it would take seven hours simmering in small pots placed over hot coals. To serve the main meal at 11 a.m., she would have to get up at 3 a.m. to cook. The flavour I create will be an evolution of that tradition. It’s not just about concocting aromas, it’s about a history.”

One of the biggest changes in new China is the way people gorge themselves. There are twice as many obese Chinese today as there were just ten years ago, and an estimated 200 million Chinese are overweight, a 40-percent increase over the same period. I point out to Lee Hiang that even if she comes up with a flavour that was an exact match, a dried-noodle product still won’t be nutritious, won’t be healthy for you, won’t harmonize your spirit. She’s helping the instant-noodle industry by giving them all these great authentic flavours, but really . . .the food’s not getting any better, is it?

“But,” she responds, “say that I make a product for Myanmar. The Burmese people don’t have much money and they want what they buy with their few cents to really taste delicious. So we give it to them. We put in beef flavours where there is no beef present, all to make the food taste better. It’s not just a simple flavouring; at the end of the day it’s about customers.”

Those of us who care about what we eat hold a vague, ironic bias against processed foods. We think them inferior even as we buy, defrost, and microwave them up for dinner. But the vast majority of the world’s population cannot afford to make value judgments about food; they need to feed their families and stay alive. If the flavour industry can give the joy of Fat Beef Hot Pot in a twelve-cent, Styrofoam noodle bowl, are they not making a positive contribution to culture, making meagre lifestyles richer?

We return to Shanghai the next day, utterly exhausted. Late that night, after the feasting and toasting of our victory banquet is done, Jeff, Willi, and I retire to the bar at the hotel. A Filipina lounge singer does a perfect Shirley Bassey imitation while we smoke Cuban cigars, sip eighteen-year-old scotch, and ruminate on the journey completed.

As the smoky-peat, cherry-sour astringency of the liquor hits my tongue, Jeff asks me my favourite dish of the trip. I stop in mid-sip. Honestly, I can’t say. In fact, I hardly remember anything identifiable as a “dish” at all. What I remember is wave after wave of flavour sensations, each distinct from the last. Perhaps with time I will once again be able to assemble them into a totality called a “dish,” but sitting here, listening to jazz, I am nowhere near that level of sensual literacy. Like my two-year-old son, I am still singing the alphabet song phonetically, not quite sure yet what is an elemenopee.

I take a pull on my Montecristo no. 4 and think about the majesty of flavour creation. Food is life. But whether a vegetable freshly picked or meat well-aged, all that we eat has begun its inexorable march to decomposition; it is slowly rotting. Food is death. We consume death to live.

Flavourings, on the other hand, have a sense of timelessness about them. They are designed to resist the natural degradation that occurs when ingredients are cooked or cooled. In their struggle to provide constancy through the manufacturing cycle they rage, if you will, against the dying of the light.

“We don’t want to resist change,” Willi argues mildly, “we want to control it. We want to design flavours that do not change before you eat them, but only while you do so.”

We sit in Shanghai where our trek began, blowing smoke into the filtered air. Life. Death. The authentic and the artificial. The yin and the yang. All things balance as we eat our way to our ends.