Have you stood in front of a newsstand lately? 400 Star-laden Pages. 115 Things To Do With Cheese. The 27 Faces Of Infidelity. Numbers and lists dominate the mediascape. Why? Is it a brutish apotheosis of private property—thoughts as things, and the more the better? Is it the end of civilization? In a word (actually, over 1,500 of them!), yes.

I don’t want to be curmudgeonly about our modern lust for lists. Culture and language sometimes evolve in slatternly ways, and today’s guilty pleasure can become tomorrow’s fresh new aesthetic. I understand the lure of lists. I recently found myself sitting in my parked car, unable to turn off Jian Ghomeshi’s cbc radio show, 50 Tracks—a public debate about who belongs on a list of the fifty most important Canadian songs ever. And although critics scorned The Greatest Canadian, I thought the show at least nudged our celebrity worship in the direction of history and public figures whose accomplishments go beyond putting their hands up the vaginas of cows (an event I regret catching on The Simple Life).

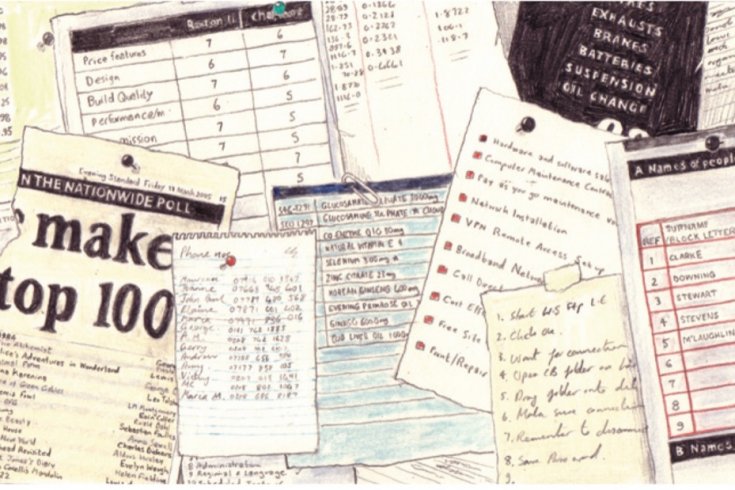

So I’m curious about what our trust in lists means—from the New York Times’ “100 Notable Books of the Year” and the Fortune 500 to the endless gush of long and short lists for book prizes. Why are we such suckers for numbers? To me, numbers flaunt a kind of bogus, unearned power, like border officials or the doormen of trendy clubs. They are tiny tyrants who don’t have to earn their authority: Hey man, I’m a seven. I come after six. Who are you? I think our childish investment in numbers and ranking reflects a cultural anxiety—a mistrust of ambiguity, real debate, and complexity. To the American public, for instance, John Kerry was both too wordy and too much like a word—too open to interpretation, fluid, unfixable. But George Bush, with a blunt self-confidence unfettered by knowledge, comes across blank and solid, like a good ol’ digit. (And he is a digit—George II). Kerry was old-fashioned text; Bush is proudly inarticulate and numerical, a president with a tidy to-do list of imperial chores.

But lists are deeply American, from the itemization of rights in the Declaration of Independence to the annual ranking ritual of the Oscars. The possibility of rising up the list from the bottom of the heap to Number One is what the American Dream is all about. Not that Americans invented the list—it goes back at least to the Ten Commandments and other itemized religious proscriptions. But Letterman’s Top Ten list may have given the form its particularly modern, arch, semi-hip tone. Canadians imagine we’re above such vulgar competition and so we’ve been slow to jump on the bandwagon. But it turns out we absolutely love to judge, rank, and ruthlessly exclude! We jammed the phone lines of Canadian Idol and formed mean-spirited voting blocks to ensure Don Cherry’s place on the short list of The Greatest Canadian. How ironic that the competitive free-for-all of The Greatest Canadian ended up enshrining a socialist like Tommy Douglas! (What’s next for the cbc, cock fights?)

Writers tend to hate lists, with their collective, unauthored look. They especially hate the short lists for book prizes. They moan that juries are “political” and they shudder at the concept of ranking books like seeded tennis players—unless they land on a short list themselves, when suddenly the idea of competing with others takes on a noble burnish.

Well, I’m a writer too, fonder of words than numbers. I like a nice indented paragraph. I was looking forward to using long, silky sentences, full of Jamesian subordinate clauses and “on the other hands” to explore this topic. I wanted to build a swell of curvy, nostalgic dunes of “running text” (as the editors of Us Weekly magazine sometimes refer to prose) to create an argument against the pandering primacy of numbers.

But . . . prose is so boring! And you have to figure out what you think about things and stuff. Better to take advantage of the crisp Armani tailoring of a list. Yes, it flatters your intellectual posture right away, just like a uniform!

So here is a list of thirteen possible reasons why, for better or worse, human beings love to list:

1. A list turns information into technology. We’re all too busy to contemplate, for god’s sake. We need to prioritize. A list is about the bottom line: Tell me what I need to know, fast.

2. A list conveys authority, hierarchy, and a sense of order. This is comforting in a world of falling towers and bad TV. A list implies that someone is in charge. A list is also post-postmodern. Everything is not relative! But we’re busy, so we need an intellectual valet—a list.

3. A numbered list seems scientific and therefore more credible than the stuttering human voice of prose. A list radiates the calm algebra of objective truth—even though most lists (and especially the short lists for book prizes) are wanton acts of subjectivity.

4. Lists prosper in times when open political debate is considered mildly treasonous. A list has the look of a corporate decision, or a memo. A list has no sense of humour. (Harper’s Index is an exception: a list of neutral statistics reorganized in the service of irony and political satire.)

5. TV shows such as American Idol, Canadian Idol, or The Greatest Canadian allow us to weed out the weaklings, an unpleasant human predisposition we never seem to outgrow. From the pecking order of the schoolyard to the high-school prom-queen competition to rating women in a bar, we love to rank and be ranked. Maybe it’s biological; we have to know where we stand with others, who the alpha males and queen bees are. Or maybe the wound of not being chosen for the dodgeball team is partly healed whenever we vote someone else off the list. When we dump the talented, unslick, slightly plump girl off Canadian Idol.

6. Lists run deep, they are primal. This is the only explanation for the success of the Bo Derek movie 10.

7. In music, the individual iPod playlist has become a form of musical expression in itself. The new version is iPod shuffle, which takes your playlist and randomizes the sequence. This has a modern, biodynamic flair, like the endless possible recombinations of the genetic code. What is the slogan for the iPod shuffle? “Life is random.” This pretends to subvert the traditional, hierarchical list—but a list it remains!

8. Numbers look more modern than words. Text messaging uses “2” and “4” because they are shorter than the words. Numbers are tidy, minimal, and lower-case: the equivalent of the neutral, non-narrative geometry of modern interior design. Words are fat. Numbers are thin. Numbers are cool.

9. Lists represent the triumph of personal opinion over evidence or informed debate. Bush didn’t need hard evidence that Iraq had weapons of mass destruction; it was his opinion that they existed, and that was enough. Invading Iraq was simply on his list of imperial to-do chores as president.

10. Lists are the spawn of journalism and the media, used to eliminate fine shadings and contradictions. The belief that truth might reside in small, incidental details belongs to the world of fiction. Journalism works on the principle of prioritizing—what belongs on the front page, what news story should lead. This requires a number of subjective decisions that create that simulacrum of objectivity—The News.

11. The indented paragraph begins to have a dated look. Magazine editors now “package” stories, breaking up scary blocks of text with sidebars, boxes, and snappy design elements intended to make print look more like TV. I can always tell the ages of my email correspondents by whether or not they use paragraphs. Punctuation, upper case, salutations—that’s for people who don’t have a life. Imagine Virginia Woolf ending a letter to Vanessa Bell with an emoticon . . . Dear Vanessa, I fear one of my headaches is coming on, so I must be brief. Do tell me what you think of my recent scribblings. ; ) Virginia.

12. Here is a list of the narrative elements of the novel Mrs. Dalloway: i) Mrs. Dalloway buys flowers for her party; ii) a former boyfriend shows up unexpectedly; iii) a variety of emotions are experienced by the hostess and her guests as the party unfolds.

13. What is the opposite of a list? A personal letter, a poem, a page of a diary, a piece of music—possibly the last bastions of uncommodified, unranked, un-numbered self-expression.

But that’s just my opinion—and opinions are what feed our appetite for lists.