“When all is said and done, the Canadian federation presupposes that, over and above our respective neighbourhoods, towns, cities, and provinces, Canada is considered to be the homeland of all Canadians. . . . Choosing to have feeble federal institutions would be to condemn ourselves to collective weakness in a world that will not be kind to nations divided against themselves. A country, after all, is not something you build as the pharaohs built the pyramids, and then leave standing there to defy eternity. A country is something that is built every day out of certain basic shared values. And so it is in the hands of every Canadian to determine how well and wisely we shall build the country of the future.”

—pierre elliott trudeau

When Canada’s first ministers sat down last fall to “fix health care for a generation,” the entire country was invited to watch live on television. Under the glare of lights, provincial premiers demanded more money and less federal interference in an area of provincial jurisdiction. Charging Ottawa with mismanaging the file, and precipitating the health-care funding crisis, the premiers exhibited noteworthy confidence. Paul Martin, the master slayer of deficits, and, as finance minister in the 1990s, the man chiefly responsible for cuts to health and social transfer payments, was now in the prime minister’s chair. Having told Canadians that a long-term health-care deal would come out of the conference, Martin winced as the demands piled up. Two days in, despite an offer of substantial and sustained federal funding on the table, the conference was deadlocked. It appeared that more money was not quite enough.

Just prior to what was supposed to be a celebratory dinner at the prime minister’s 24 Sussex Drive residence, Quebec Premier Jean Charest told Martin that multilateral discussions were futile, and demanded instead bilateral negotiations between his province and Ottawa. The cameras were shut off, and Martin instructed Alex Himmelfarb, one of his senior advisers, to broker a deal. A full day later, closeted federal and Quebec officials failed to reach common ground. Pushing functionaries aside, Martin finally intervened, and, in the end, accepted Charest’s original demand of federal funding with no real strings attached. The trade-off, in order to pacify Alberta and to ensure agreement from the other premiers, was that, vis-à-vis the ten-year $41 billion health-care package, the same deal must, in essence, be available to all provinces. Without hesitating, Charest agreed.

Martin trumpeted the agreement, calling it “a deal that really embraces the reality of Canada and I am very, very proud of it.” He further described it as “a deal for a decade” and declared “asymmetrical federalism” henceforth the order of the day. It was a sound bite accepted by many journalists and by Liberal Party stalwarts determined to stand by their leader in a minority government. But with a Liberal Party leadership review slated for this March, rumblings of discontent can now be heard. The hushed question has become “Did Martin sell the farm?”

Quebec, long in the constitutional wilderness and refusing to participate in most federal-provincial agreements, is now the lead advocate of “interprovincialism,” and the cleavage dividing the nation no longer falls along the English-French axis, but rather is the provinces versus Ottawa. While there is language in the new health-care accord allowing the federal government to claim victory—the provinces are instructed to abide by the dictates of the Canada Health Act and report on universality, etc.—only time will tell the story of regional compliance. Meanwhile, a principle has been endorsed that sets up the possibility of “sovereignty- association” not just for Quebec, but for all ten provinces.

Charest returned home maintaining that the agreement was the beginning of a new series of initiatives to rectify the fiscal imbalance and lessen the temptation to centralize. He received a hero’s welcome. Paul Martin may be “very proud of it,” but many Liberals believe that when a Quebec premier (of whatever political stripe) is in the ascendancy, there is trouble afoot. On Parliament Hill, one can hear the whispers: “Pierre Elliott Trudeau, it would have never happened under Pierre Elliott Trudeau,” and disquiet about the “reality of Canada” as Mr. Martin sees it. To many, it represents national vivisection.

Watching the September 2004 events unfold filled me with disbelief and, yes, memories tinged with nostalgia. In the early 1980s, with the economy in a tailspin, an energy crisis threatening both treasuries and lifestyles, and the country politically divided over social issues, somehow the most critical matter of the day was to bring Canada’s constitution home from Britain, and to knit Canadians together as one nation, with all its citizens subject to the same rights and responsibilities. It was Prime Minister Trudeau’s vision and the constitutional conference of 1981 was convened to hammer it through.

My generation knows the scene well. We watched on television as Trudeau attempted to impose his iron will, insisting that Canada must be more than the sum of its parts. We watched, as the conference tilted toward a stalemate between Trudeau’s charter-based nationalism and emphasis on individual rights, and the “two nations” vision of Canada embraced by most Quebecers. Then, we learned, sequestered away from the main gathering, three old friends—Ontario’s Roy McMurtry, Saskatchewan’s Roy Romanow, and Ottawa’s man Jean Chrétien—huddled around a kitchen table in the Ottawa Conference Centre to negotiate a deal. It is no wonder that the “kitchen chat” included a representative from deal-making Ontario, a Prairie New Democrat with centralist leanings, and Chrétien, a man who supported Trudeau’s drive to keep “Quebec in its place—Quebec’s place is in Canada.”

The next day, the deal was signed. “Behind his Oriental impassivity, one could feel Trudeau literally rejoicing,” said René Lévesque shortly thereafter. “He had put one over on us.” To Lévesque, the accord signed by Trudeau and the nine English premiers was uniquely Canadian, orchestrated “behind Quebec’s back to insure Quebec’s servility to the anglophone majority in Canada.” The memory of Quebec’s “humiliation,” which became known as “the night of the long knives,” has shaped federal-provincial relations ever since.

From 1984 to 1993, as the chief pollster for the Mulroney government, I was in charge of taking the nation’s temperature on constitutional matters. Twice, through the Meech Lake and Charlottetown accords, Canadians said “No” to special status for Quebec, and I very much doubt that this sentiment has changed since. In 1992, on a sweltering late summer’s day, I looked down the barrel of certain defeat of the Charlottetown Accord and tried to explain to then-constitutional minister Joe Clark the dilemma he faced. Sitting in the prime minister’s office in the Langevin Block, I told him, “Right now, the onlyl package a majority of Canadians are prepared to accept would involve giving the ‘Rest of Canada’ those things that Quebec is asking for.” Clark’s view was that such an arrangement would emaciate the federal government, leaving it without the capacity to set national standards.

On offer in the Charlottetown referendum—and in the Meech Lake Accord before it—was, in fact, asymmetrical federalism. It codified conventional practice since the patriation of the Constitution in 1982, namely, that Quebec could opt out of national programs and, provided it administered comparable programs, would continue to receive full compensation from the federal government. In the end, Charlottetown was too much for English Canada and not enough for Quebec. The “Rest of Canada” was unwilling to grant this special prerogative to Quebec, and Quebec rejected the principle that Ottawa had the right to spend funds in areas of provincial jurisdiction.

In the decade following Charlottetown’s defeat, federal-provincial relations muddled along without formal agreements. This laxity contributed to the near-death experience in the 1995 Quebec referendum on sovereignty, a razor-thin victory for the “No” forces. But the confluence of other factors appears now to have resulted in Paul Martin granting to all provinces that which Quebec wants. By charting a course that Canadians had previously rejected, he now runs the risk of setting Canada on a path toward dissolution.

Whether the Fathers of Confederation would have preferred a more centralized state is open to debate. But there is little question that the “French fact” and the need to accommodate Quebec forced Canada to divide “sovereign powers” between two orders of government. It appears that first Prime Minister John A. Macdonald favoured real power in the centre as the provinces were granted authority over “matters of merely local and private nature,” while Ottawa assumed the broader “peace, order and good government” mandate and grabbed a “residual power” encompassing everything not spelled out specifically in the British North America (bna) Act.

Our constitutional framers never envisaged that issues of “local and private nature” (health care, education, welfare, etc.) would come to matter more to Canadians—and indeed shape our national identity—than the more nebulous or distant prerogatives of the federal government. Furthermore, although the division of powers was laid out in the bna Act, that document was silent on many matters central to Canada’s development: political parties, the roles of the prime minister and cabinet, and the evolution of federal-provincial relations. According to the constitutional scholar Alan Cairns, Canada has been governed by a “living constitution,” malleable and evolving organically, modified more by convention and necessity than by legal precedent.

For decades the power and authority of the two levels of government ebbed and flowed, but by 1940 the ravages of the Depression and a newfound nationalism emerging out of Canada’s war efforts conspired to force a change. That year, the Rowell-Sirois Commission concluded there was a need for a larger federal role in Canada’s social programs to help protect against future economic calamities. Four years later, Ottawa responded by introducing family allowances and, in so doing, established a precedent of federal spending in areas of provincial jurisdiction.

Even more seminal in shaping federal-provincial affairs was the introduction of equalization payments in 1957. Newfoundland had ended its isolation eight years before, and, with regional disparities apparent to all but the blind and/or greedy, Ottawa began transferring funds to “have not” provinces. Inherent inequities militated against full participation in the country’s growing fortunes, and to keep Canada whole and prevent parts from fracturing it was widely accepted that Canadians needed to be each other’s keepers.

This was national-character-defining legislation, and Quebec was a willing partner. While Premier Maurice Duplessis rattled his sabre at Ottawa from time to time (over such intrusions as federal grants to universities), the province was quietly trying to transform itself from a rural, sectarian society into an urban and secular one, and needed to keep the doors open to such federal initiatives.

In 1963, responding to a more aggressive Premier Jean Lesage and his demands to be “maître chez nous,” the federal government demonstrated its flexibility by appointing the Royal Commission on Bilingualism and Biculturalism. The commission reaffirmed that Canada was a partnership based on a historical “pact” between English and French. But this attempt to build bridges was being undermined by massive, multi-ethnic immigration into English Canada. Prior to official multicultural policies, these new Canadians felt little fealty to historical pacts, and were beginning to make demands of their own. Concurrent with this trend was the rise of dissenting voices by provincial governments—i.e., by those jointly responsible for the new entrants—over the federal government’s superior revenue- generating capacity through the Income Tax Act.

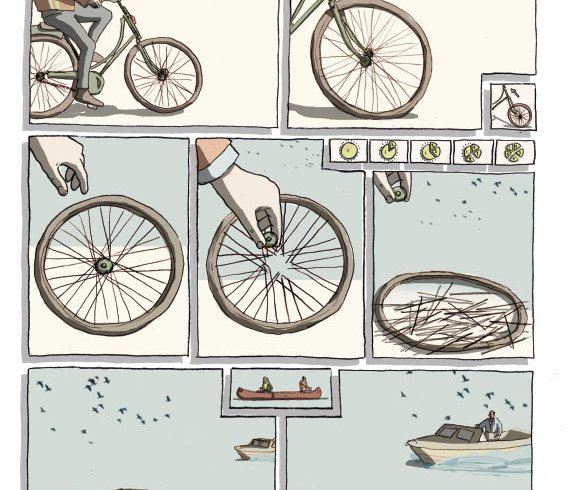

Prime Minister Lester Pearson set out to smooth waters through “co-operative federalism,” wherein national programs would be funded on a 50:50 shared-cost basis and any province that wished to opt out could do so and still be fully compensated. Under this scheme, federal-provincial relations flourished. Medicare, the Canada Pension Plan (cpp), the Canada Assistance Plan, and funding for post-secondary education were all introduced. These areas of “provincial jurisdiction” now had a federal godfather and were part of a network of policies binding the country together. Irresistible as it was to the other nine provinces, Quebec nonetheless took Ottawa at its word and opted out of the cpp, choosing to set up its own plan. This move, the University of Toronto historian Michael Bliss told me, was “the camel’s nose in the tent.”

When Trudeau came to power, he moved away from unconditional transfers. He insisted that Ottawa’s job was to curb the excesses of the regions, and he set out to enforce a national vision around which geographic and ethnic differences would be forced to bend. In 1971, with the memory of tanks on the streets of Montreal still raw in the public consciousness and debate still swirling about his imposition of the War Measures Act, Trudeau gambled that the time was ripe for change. But, at the constitutional conference in Victoria, B.C., he failed to get agreement on a package of reforms when Quebec demanded more control over its own social programs. Dejected, Trudeau stewed for almost a decade before finally threatening to unilaterally patriate the Constitution. All took note, especially in Quebec.

Quebec’s growing sense of exceptionalism would not be daunted by Trudeau’s bloodless rationalism—indeed, the push for independence, many argued, was accelerated by Trudeau’s inflexibility—and, in 1976, Quebecers lined up behind Lévesque, voted the Parti Québécois into power, and awaited the promise of a referendum on sovereignty. Said Lévesque in his victory speech: “On n’est pas un petit peuple, on est peut-être quelque chose comme un grand peuple.” (“We are not a small people, we are maybe something of a great people.”)

With his strong disdain for regionalism, especially in the form of Quebec nationalism, during the 1979 federal election campaign Trudeau dismissed Joe Clark’s “community of communities” vision of Canada as tantamount to reducing Ottawa to little more than a “headwaiter to the provinces.” The country was on a knife edge, with Trudeau ever steadfast in his rejection of special status for Quebec, but saying, in a rare display of accommodation, that a “No” vote in the 1980 referendum would be interpreted as “a mandate to change the constitution, to renew federalism.”

The much more decisive 1980 “No” vote (60:40) was, of course, followed by Quebec’s “humiliation” at the 1981 constitutional conference. Ever since, regardless of the party in power in Quebec City, “parallelism”—the notion that Quebec identity demands that it craft and administer its own programs parallel to, and not in tandem with, either the federal government or the other provinces—has become orthodoxy in Quebec politics.

Like all Quebec-based politicians, Brian Mulroney was in awe of Trudeau and worried that his tenure as prime minister would pale in comparison to The Great Man. Trudeau’s crowning achievements, Mulroney believed, were the Charter of Rights and Freedoms and the patriation of the constitution; his greatest failure, Quebec’s absence as a signatory to the deal. More than the Free Trade Agreement, the Meech Lake Accord was to be Mulroney’s legacy, and proof that he was Trudeau’s better.

Never before had Canada’s elites lined up so solidly behind a single initiative as they did the Meech Lake Accord. All three political parties, business leaders, and virtually every newspaper endorsed it. When Elijah Harper, the Cree member of the Manitoba legislature who held up an eagle feather protesting the Accord, together with Newfoundland’s Clyde Wells, killed the deal, it was viewed as a short pause in the movement forward, a minor irritant to be overcome through a national referendum on the Charlottetown Accord. That unassailable agreement would finally bring Quebec fully into Canada’s bosom.

On Charlottetown, the initial opposition was the lonely voice of Reform Party leader Preston Manning. His message was straightforward: “For the love of Canada, vote ‘No.’ ” While there was plenty in the accord to satisfy Manning (and his like)—Senate reform, unanimity for constitutional amendments, etc.—to him, special status for Quebec was un-Canadian. It was a simple and powerful point that soon resonated among special-interest groups, and those representing women, the poor, and aboriginals added their voices to the mounting opposition. Their concern was less about Quebec’s special status, and more about the failure to grant rights broadly, with fears that the fine print allowed provinces to opt out of federally sponsored social safety-net programs.

In the end, Charlottetown marked both the defeat of asymmetrical federalism and the notion that Canada was a pact between English and French. Instead, English Canada endorsed a vision of symmetrical federalism, where all provinces were to be treated equally. For their part, Quebecers simply viewed Charlottetown’s demise as emblematic of a Canada determined to blunt their national aspirations. Bloc Québécois member of parliament Gilles Duceppe announced: “The way I see it, the population is standing in a kind of steam bath armed with baseball bats. The first to open the door gets one heck of a shot in the mouth.”

The failures of Meech and Charlottetown alienated Quebecers and emboldened Western Canada. The formation of the Bloc Québécois and the entrenchment of the Reform Party redrew the map of electoral politics and, in the 1993 election, led to the near destruction of the Progressive Conservative Party of Canada. The near-tie result of the 1995 Referendum on sovereignty proved that Quebec separatism was alive, and ignited a flurry of debate inside the federal Liberal caucus concerning the next move on the constitutional chessboard.

Prime Minister Chrétien and his chief strategist, the cerebral gutter-fighter Stéphane Dion, came up with a Plan A and a Plan B. The first was a series of efforts to placate Quebec; if that failed, the second would bring the province to heel. The ill-fated sponsorship program and a parliamentary declaration that Quebec was distinct was the carrot; the stick was a Supreme Court ruling on the legality of Quebec’s right to secede and the Clarity Act, a stern piece of legislation that spelled out precisely the terms and consequences of separation.

Having personally experienced the hothouse environment that is the prime minister’s office, I learned to expect the unexpected. Nonetheless, I was astounded by the audacity of Chrétien’s Plan B. In the early 1990s, our polls showed that nearly one-quarter of Quebecers were “soft separatists” who held conflicting views about Canada and sovereignty. They aspired to a more independent Quebec, sure, but only if an economic union (including a common dollar and passports) with the rest of Canada was part of the arrangement. We were always wary of turning soft separatists into hard ones. Chrétien and Dion read the situation differently. They gambled that by telling Quebec an ambiguous referendum question would not be tolerated, and that there might be no economic union if they voted against Canada, the soft separatists would relent and the endless threats would cease. Like Mulroney before him, it was now Chrétien who rolled the dice.

To my great surprise the Clarity Act was not met with howls of protest. Instead, the illustrious saviour of the Quebec sovereignists, Lucien Bouchard, quietly retired, and Jean Charest, the one-time leader of an almost defunct Tory party but with a strong commitment to Canada, won the next Quebec election. To the relief of most, Canada tucked the constitution under the pillow and went back to sleep.

But under this calm exterior, non-constitutional forces were taking shape that would alter the nature of modern federal-provincial relations as much as the cataclysmic events of the early 1990s. Principal among these were a mushrooming federal debt and new realities emerging from free trade with the U.S. By the turn of the century, these forces would lead to a virtual putsch, orchestrated by Jean Charest, and fully manifested at the 2004 health-care conference. Paul Martin’s acquiescence to Charest’s bold move has reshuffled federal-provincial relations and made Trudeau-Chrétien Liberals, among others, question Canada’s very survival.

In 1995, few grand schemes or new national programs ran through Finance Minister Paul Martin’s mind as he prepared the budget. His officials had convinced him that the deficit problem was structural and required drastic measures. They indicated that the Mulroney government had actually run operational surpluses in its latter years, but that the crippling interest payments on the debt had masked any credit the Conservatives might have otherwise received for their efforts. Tinkering around the edges would not work. The cuts would have to be deep, and the pain downloaded to the provinces.

Fortunately for Ottawa, there was always the necessity of dealing with competing and inherently unequal provinces. (A premier’s position on offshore resources, for example, could be reliably predicted based on whether or not his province had resources and/or a shore.) And playing one province off against another, or, to put it more charitably, ameliorating tensions, gave Ottawa legitimacy as the final arbiter of national interest.

It was to be a historic budget and, his focus never too far off the big prize, Martin knew that program-cutting always created more enemies than friends. Knowing that slashing across the board would produce public outrage, Martin opted for less attention-getting cuts—to Defence and to Established Programs Financing, the transfers to the provinces that paid for a portion of health care and postsecondary education.

In provincial capitals, Martin’s move highlighted the inherent problems with shared-cost programs and with federal spending power. Everything was fine as long as federal and provincial priorities meshed, but when one side changed—in this instance, the federal government’s commitment to deficit reduction over social spending—the other was left with the same costs and fewer funds to cover them.

Martin’s cuts galvanized the provinces into more collective and cohesive action. Under Chrétien, Ottawa de-emphasized first ministers’ conferences. In response, the provincial premiers resuscitated the annual premiers’ conference, and, at their Calgary meeting in 1997, produced a startling declaration: “In Canada’s federal system . . . the unique character of Quebec society, including its French-speaking majority, its culture and tradition of civil law, is fundamental to the well-being of Canada. Consequently, the legislature and government of Quebec have a role to protect and develop the unique character of Quebec society.” The Calgary declaration went on to state, “If any future constitutional amendment confers powers on one province, these powers must be available to all provinces.”

Resolutely maintaining their post-patriation sulk, Quebec was not party to this agreement. The “sitting premiers” recognized, however, that reforming the federal-provincial power imbalance was impossible without Canada’s second-largest province. Only a united front would succeed. Post-Meech and Charlottetown, the nine premiers also realized (after much agonizing) that their previous insistence on equal treatment for all provinces was a non-starter for Quebec and that they must satisfy its demand for even greater autonomy.

Meanwhile, another change was producing cleavages of a different sort. Free trade with the US was realigning provincial commerce from an east-west to a north-south axis and creating increasingly distinctive and dissimilar regional economies. In 1989, only Newfoundland exported significantly more of its products to the US than to the rest of Canada. By 2001, every province but Manitoba had a bigger trade balance with the U.S. than with their sister provinces. And this continuing trade activity is making east-west links ever more tenuous.

Quebec and the other provinces finally had something in common: Their trade focus was now outside Canada, and, as their economies evolved differently, the benefits of staying together as one cohesive unit—and being treated equally within that unit—were diminishing.

Jean Charest was a reluctant entrant into the hurly-burly world of Quebec politics and, initially, the “golden boy of Canada-Quebec politics” had his image more tarnished than burnished. In Quebec, support for a leader is based on defending the province’s interest, and, until recently, the former federal Tory was mostly failing the test. Fighting his former mentor, Lucien Bouchard, on the hustings, and accused of being a turncoat, Charest seemed to have the cards stacked against him. Though victorious in the provincial election in 2003, his government soon found itself in trouble, as a majority of Quebecers recoiled at the Liberals’ initial volley of cost-cutting and union-busting.

Ultimately, Charest knew that the constitutional file lies dormant in Quebec for only so long and that success meant, at least, bringing the province in from the wilderness. Charest’s ascent actually began quietly in the fall of 2001, when his party released “An Action Plan: Affirmation, Autonomy and Leadership.” It was a bold document asserting that Quebec’s interests were best pursued within the framework of federalism. The rest of the blueprint insisted, however, that federal-provincial relations would have to be radically altered if those interests were to be satisfied.

At a time when interprovincial trade was becoming less significant, Charest’s new federalism was defined by increased “interprovincialism” and a new alliance with the other provinces. The agenda was clear: reduce the federal- provincial fiscal imbalance; recover tax points from Ottawa; limit federal spending power; and gain a greater role for provinces in international treaties and agreements, including those with the World Trade Organization and the Free Trade Area of the Americas. The demand for the reinstatement of a veto and constitutionally guaranteed representation on the Supreme Court were added for good measure. The vehicle to achieve this agenda was not another round of constitutional negotiations or referenda, but a Council of the Federation, through which Quebec would play a leadership role. Charest was building a Trojan horse to house the ambitions of Quebec and was going to recruit the other premiers to roll it up to the gates of Parliament Hill.

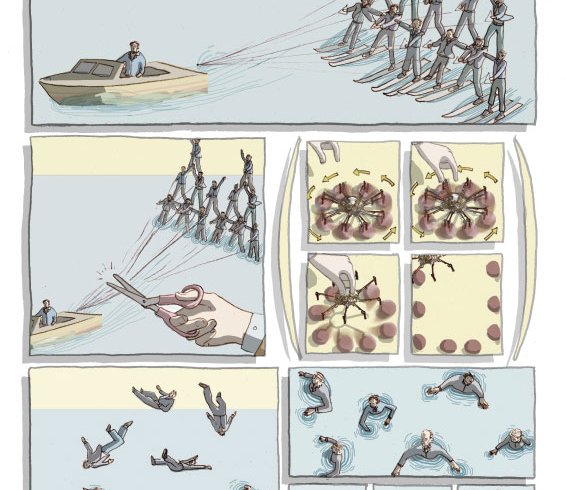

By advocating “interprovincialism” and uniting the provinces under the Council of the Federation, Charest was staring down “divide and conquer federalism” and confronting Ottawa with an alignment of virtually identical interests. All the provinces agreed the federal government should address the fiscal imbalance by transferring more funding, if not tax points, to them; all wanted unique arrangements with Ottawa to better conform with their particular economic conditions; and a number sought more direct authority to strike deals with their increasingly important trading partners to the south.

One thorny problem remained. While the premiers were united in their desire to squeeze more money out of Ottawa, national programs—and none more so than health care—formed a major part of the Canadian identity. The solution was to resolve that all provinces had an equal right to opt out—a prerogative that the nine non-Quebec premiers were unlikely to exercise, at least not at this point in time. With this compromise, Charest was extending Quebec’s historic insistence that Canada was two nations to the idea that it now consisted of ten.

Two days into the September 2004 health-care conference, Paul Martin didn’t know what hit him. His own staff, renowned for their research and exquisitely calibrated political antennae, had apparently failed to alert the prime minister about the extent of trends in provincial capitals. When Martin, having impetuously trapped himself by telling Canadians that a health-care deal would come out of the conference, finally agreed that he could concede to the provinces’ demands only if Quebec agreed that the other provinces get similar treatment, the premiers knew victory was theirs.

Martin was outflanked by a Quebec premier who proved himself as capable of manipulating federal-provincial affairs in favour of the regions as Ontario had historically been brokering deals favouring Ottawa, and as capable of defending provincial rights as Trudeau had been in defence of Canada. Charest returned to Quebec to a hero’s welcome. The province had been brought in from the cold, and the ghosts of Lévesque, Parizeau, Bouchard, and others were vanquished by a canny “Quebec Liberal” who, in effect, won sovereignty-association through federal accommodations.

Charest maintained that the agreement was the beginning of a new series of initiatives to rectify the fiscal imbalance and make sure Canada “resists the temptation to centralize.” In a speech last November, he offered his own version of history, saying, “Our country was constituted federally, specifically to establish an asymmetrical system, to allow for differences . . . . Indeed, each province joining Confederation was treated differently . . . . When Quebec is the sole government responsible for implementing a particular international agreement, it should clearly be the one making the international commitment.” He further added, “A Quebec jurisdiction at home remains a Quebec jurisdiction in international relations.”

In the post-conference discussions concerning the promised national childcare policy, Quebec argued that because it already had the best program, not only would it not abide by national standards, it would do nothing new, and simply accept its share of federal funding. If previous accommodations allowing Quebec to opt out of the national programs qualified as “the camel’s nose in the tent,” we are now seeing the rest of the camel.

Pierre Trudeau set modern constitutional wheels in motion to stop what he viewed as a cycle of blackmail, where one province held up the national interest by bargaining solely for its own parish. The precedent embodied in the most recent health accord is an invitation not for one blackmailer, but for ten. Taken to its logical conclusion, this is Frankenstein federalism, with Ottawa sleepwalking as the nation is reduced to a patchwork quilt of unequal parts.

On health care, the disparities are already obvious. Some provinces charge their residents annual premiums, while others do not. Pay-as-you-go fees for access to private care are tolerated in some jurisdictions, and not in others. Last year, Alberta joined Quebec in refusing to participate in the newly created Canada Health Council, after Premier Ralph Klein had mused that Alberta might withdraw from the Canada Health Act altogether. Should the Supreme Court rule that same-sex marriage is legal, Klein has threatened to invoke the notwithstanding clause to ensure this right would not apply to his province. The implementation of the Kyoto Protocol is similarly threatened by Alberta’s assertion of “provincial rights.” This “firewall mentality” can be viral. Newfoundland’s Danny Williams left the most recent first ministers’ meeting taking umbrage at the reasonable proposal of retaining 100 percent of offshore oil revenues if Ottawa’s contribution to Newfoundland’s equalization payments could be “capped” once its economy equalled Ontario’s.

In the end, providing generalized opt-out options sets up the very real prospect that any provincial government may take a pass on any new program that does not meet its taste. On immigration, demographic studies indicate a looming labour shortage and suggest that Canada must dramatically increase its annual quota and take advantage of skilled labour pools in Asia. But even if Ottawa sets new immigration targets, BC, for example, could declare it already has too many immigrants and refuse to co-operate with new initiatives. Infrastructure funds for cities might be redirected by rurally populated provinces for use in agriculture instead. A new national student-loan program might be accepted by one province and rejected by others because they have different policies concerning university tuition.

The premiers have further stated that the concessions won to date are insufficient to meet their larger demands for pan-provincialism. They announced their intentions to use their “unique relationship . . . to enhance the profile of Canada in the United States” and “to help to resolve trade disputes.” Charest has revealed that this means that provinces will have the power to enter into bilateral negotiations with the US on matters of provincial concern. So, while harbouring no ambitions to form provincial armies or set foreign policy, BC might lead negotiations on softwood lumber, Alberta on beef, etc. Again, on the surface this seems innocent enough, but how likely is it that a BC delegation—with a vested interest in higher lumber prices—would be mindful of the needs of Saskatchewan or Ontario whose interests might be quite different?

As talks concerning continentalism—expanding nafta, combined with defence and perimeter-security co-operation—heat up, how can a weakened and marginalized federal government champion Canadian interests? And, on the other side of the equation, with regional economies becoming increasingly independent at home, but increasingly dependent on the vagaries of the US market and trade policies, how can the provinces defend their individual interests against the world’s only superpower? And how can an increasingly fragmented nation stand up to those voices on both sides of the border advocating seamless integration between our two nations?

National vivisection will not happen overnight but, as they have said for decades in Quebec, through “the politics of little steps.” It begins with unequal access to services, continental drift, and unequal rights, and then mutates into the erosion of any sense of shared, national purpose.

In the shadow of the Rocky Mountains rests one of the most breathtaking and majestic golf courses in the world. It has two levels of green fees—one for Albertans and a higher one for all others. The rationale is that because Albertans have used their tax dollars to develop the property, they “deserve” to benefit from their investment. This justification has nothing to do with golf. Rather, it is a reflection of a mindset and belief system that speaks to a sense of entitlement and proprietary exclusion. When what is considered by Canadian citizens to be “ours” excludes other Canadians, it is a small step before a shared national vision becomes “every man for himself ” provincialism. Is it only Alberta’s oil, only Quebec’s hydro-electricity, BC’s salmon, or Newfoundland’s potential offshore reserves? After three decades of mining national public opinion, I doubt such fragmentation would be embraced by a majority of Canadians in any single province, and I find myself remembering Trudeau—“Choosing to have feeble federal institutions would be to condemn ourselves to collective weakness in a world that will not be kind to nations divided against themselves”—and awaiting the next side-deal that will push Quebec ever closer to full independence.