In the summer of 1970, Shelly Grimson, a twenty-two-year-old university student with long hair, an army jacket, and a camera, was sent on a mission by poet and editor Gary Geddes: spend three months in and around Toronto taking pictures of an increasingly influential cabal of Canadian poets. Grimson threw himself into the work, and a handful of his portraits were published in the landmark anthology 15 Canadian Poets (Oxford University Press, 1970), edited by Geddes and Phyllis Bruce. Grimson tossed the rest of his film into a drawer and traded a career in photography for one in criminal law, and then real estate. Thirty-two years later, in the fall of 2002, Grimson opened the drawer to rediscover more than a thousand negatives.

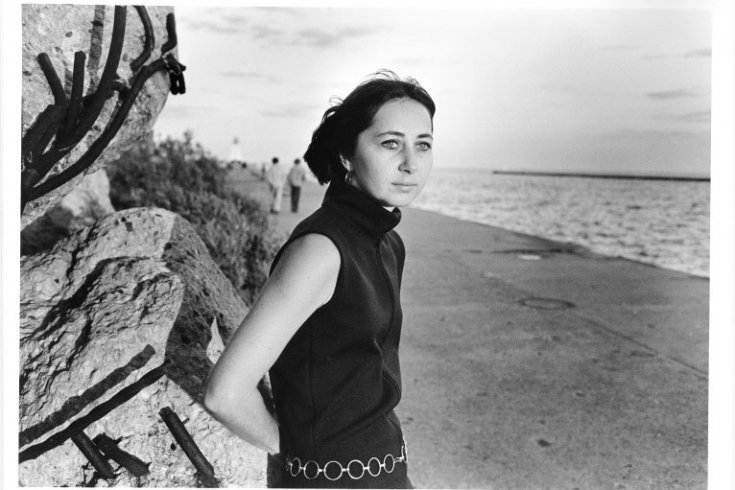

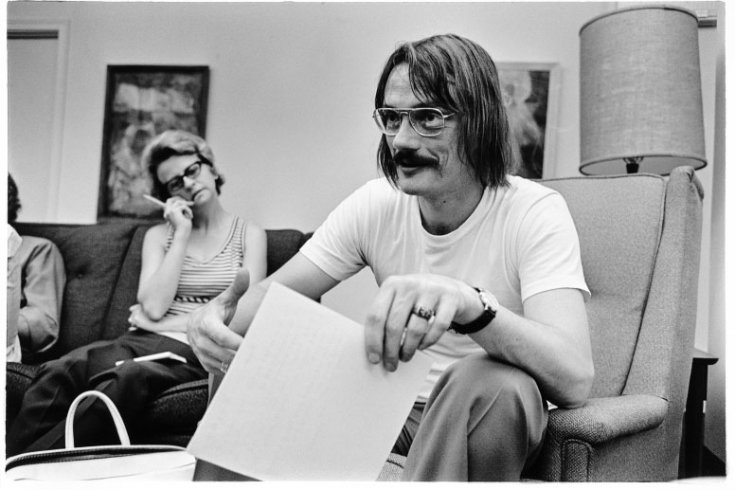

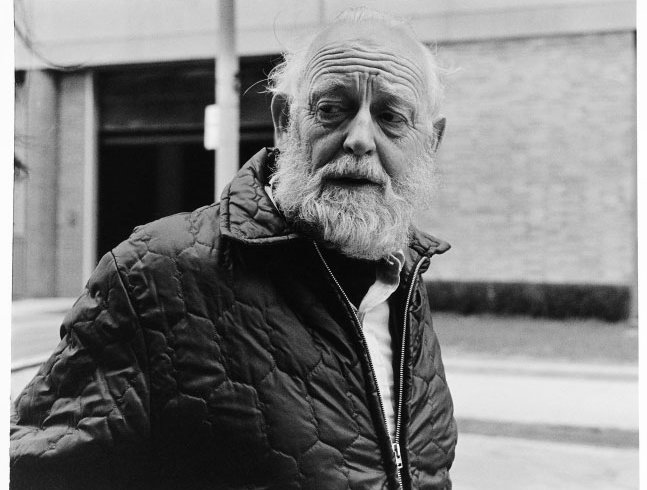

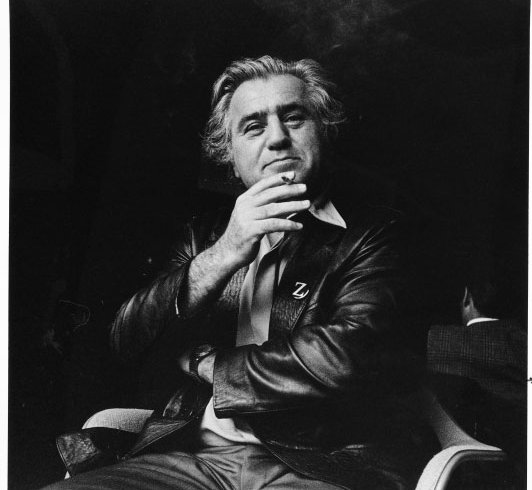

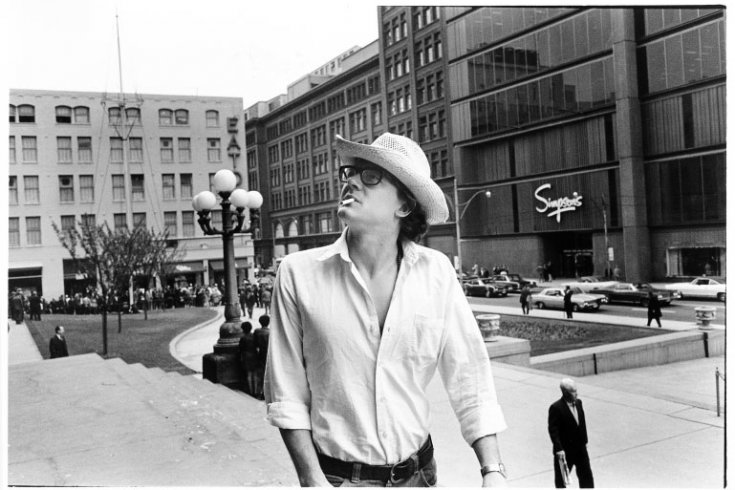

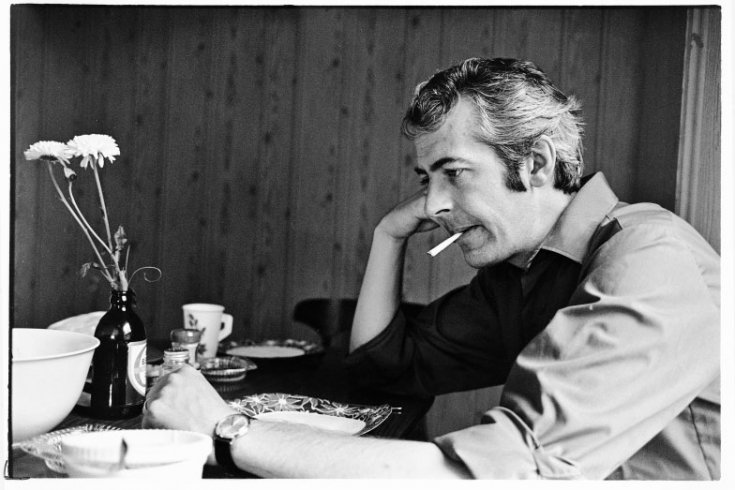

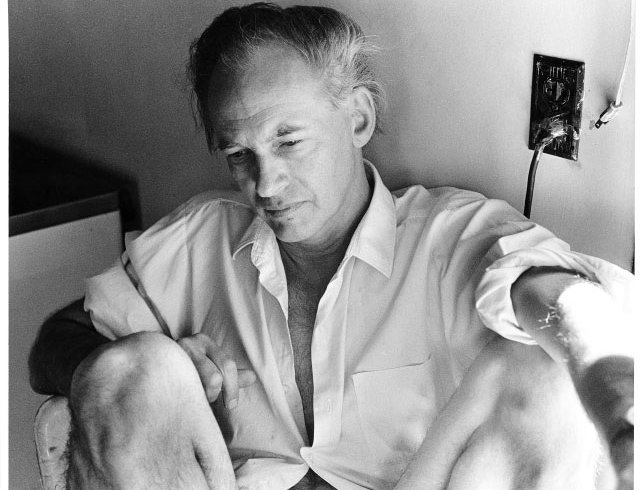

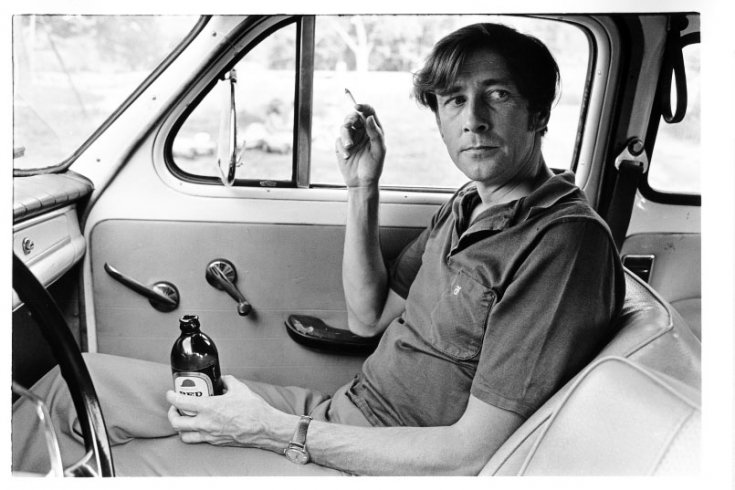

He built a darkroom in his home, and spent a year and a half printing hundreds of photographs, including the thirteen portraits shown here: Earle Birney having a nicotine fit on Charles Street; Margaret Atwood on Toronto Island; Michael Ondaatje inside the now demolished greenhouse at College and University; Margaret Avison at Evangel Hall, a Queen Street mission; Patrick Lane outside Old City Hall; John Newlove and Al Purdy on Ontario farms; Raymond Souster, banker, poet, and publisher, in front of Saint Michael’s College, on Bay Street; George Bowering and Irving Layton at York University; Gwendolyn MacEwen on a Toronto beach; Milton Acorn in a ravine; and D.G. Jones drinking in Michael Ondaatje’s car.

“The Bohemian Embassy was a coffee house on St. Nicholas Street [in Toronto] where they had a weekly poetry night. If you were a poet wandering through town, that’s where you would read. They had painted the inside black, and they had an espresso machine, the first one anyone had ever seen, which was worshipped like a god. The poetry scene was like an anthill – if you didn’t know it was there, you would think nothing was going on, but once you were in it, there was much furious activity: people reviewing one another’s books, people attacking one another, people praising one another, people having affairs with one another, and people striking up friendships. Some of them would be refugees from respectable life, and some would be patrons of the arts, and they would do things such as take Milton Acorn home to stay the night, because he wouldn’t have a place.

“On one memorable occasion, at a beautiful house, which had all-white upholstery, he [Acorn] fell into the fireplace and got covered with soot, and then went into the beautiful white bathroom and had a bath. In the morning there were black handprints everywhere.

“Many people had been writing secretly; suddenly there were places where they could get published. It was like opening a floodgate; a surge poured through. You wouldn’t find that now because the floodgates aren’t closed, there’s no buildup – you don’t get a sudden explosion.

“John Newlove was in some ways the most representative of that early group, because he was a complete loner. He came from rural Saskatchewan, and he made his own way. There were no grants, or creative writing programs back then.”

—Margaret Atwood

How beautiful we all were. Even Milton Acorn in his way. It was the summer of 1970, exactly half my life ago. I’m twice as old now as I was in the picture [opposite]. It’s a real two-pronged feeling looking at these pictures. You think, oh God, these sweet people. And then you think, oh God, but we’re all old now. They kind of mock us. Poetry was a big deal in the Sixties. It was part of the counterculture. There was rock ‘n’ roll, but poetry was somehow there before rock ‘n’ roll. We were on two crests back then. There was an international crest, which had to do with the movement of poetry off the page and out of the university, into the coffeehouses and magazines, and onto the street. But we were also part of Canadian history. A few years before that, there were maybe two or three anthologies of Canadian poetry published. All of a sudden there were all these new presses: Coach House, House of Anansi, Talonbooks, and Contact. So the number of poets was accelerating. More and more of them were showing up all the time. We read each other’s books, edited each other’s poems, travelled across the country to read. There were a few who had been my heroes, who were older than me, like Margaret Avison, Irving Layton, and Raymond Souster, who I didn’t see all that often. But some people I saw all the time, like John Newlove and Margaret Atwood. It’s a good thing that Raymond Souster was there. He was kind of a bridge between his generation and our generation. Souster ran Contact press. He published my first book, John Newlove’s first book, Margaret Atwood’s first book, Milton Acorn’s first book. This was a whole generation that wanted to know how to make a poem. You couldn’t just get by on personality and friends.”

—George Bowering