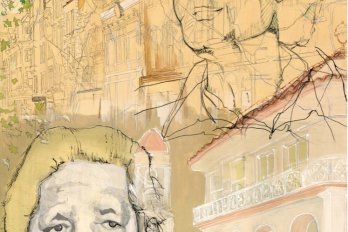

caracas — Despite previous disappointments, I always retain the faint hope that the hotel I have booked will turn out to be a delightful little place that perfectly captures the local charm of my foreign destination – in this case, Venezuela. So it is with a particular thud in my heart that I arrive at the front door of a Holiday Inn-style hotel, cut off from downtown Caracas by a network of expressway-like roads and attached to a sprawling indoor shopping centre, which comes about as close to capturing the authentic sights and sounds of Venezuela as, say, the West Edmonton Mall.

Looking on the bright side, I figure that such a dreary complex will at least be safe. After all, it’s in a well-to-do part of town, far from the desperate poverty of the shantytowns that surround the city. But, it’s the well-to-do parts of Caracas that are actually the dangerous ones. The week before my arrival, anti-government agitators in an exclusive neighbourhood near the hotel had started bonfires and set up barricades in the streets. It’s the rich who are agitating in Venezuela these days, hell-bent on overthrowing their left-leaning, democratically elected president, Hugo Chavez, whom I have come here to interview for a book on the geopolitics of oil.

Chavez himself comes from modest roots (the son of low-paid schoolteachers), and he swept to power in 1998 with massive support from the nation’s poor, who make up well over half of the country’s population. Since then, the well-to-do in Venezuela have been pushed out of their privileged positions running the country and been left raging from the sidelines. They now seem to spend much of their time plotting Chavez’s downfall. A key tool has been their ownership of local TV stations, which, along with exhaustive coverage of Hollywood celebrities, focus tirelessly on the evildoings of the president. In the highly polarized atmosphere that’s resulted, the elite has collected enough signatures to force a recall referendum on Chavez’s presidency; the results were still pending at press time.

Back in April, 2002, a faction of the elite, headed by a prominent business leader, organized a coup in which Chavez was taken prisoner. But no sooner had the fashionable set turned up at the palace in their finery to celebrate than tens of thousands of poor people clogged the streets, demanding their president back. Much of the army ended up siding with Chavez, who had risen through army ranks himself. Within forty-eight hours, Chavez was back in charge, more than ever the hero of the poor and the scourge of the rich.

For a guy who remains in the crosshairs of the country’s powerful elite, Chavez is remarkably cool. Trying to get into a public event where Chavez was speaking, I was asked for my press pass. Since I didn’t have one, I flashed the most official-looking thing I could find – my University of Toronto library card. Several guards scrutinized it carefully and then, without even checking for overdue books, waved me through. I suspect my Rogers video card would also have worked.

Security is a little tighter at the presidential palace. But once inside the iron gates, I discover a lovely colonial-style palace, all gleaming white, with a courtyard full of palm trees and flowers, and rooms with intricately carved, gold-trimmed furniture and elaborate chandeliers. Crisply dressed waiters serve guests ice-cold drinks from silver trays. I’m led through a stately room where historic dignitaries stare down from heavy portraits high on the walls. A sudden turn and we’re heading up an unadorned back stairwell to a small, rather ordinary conference room, where Chavez rises to greet me, wearing casual garb and Hush Puppies.

Venezuelan presidents are typically distinguished-looking white men, descendants of the country’s Spanish conquerors. But Chavez is part black, part Indian, a descendant of the conquered people whose traditional place at the palace would more likely be in the pantry. This seems to irk the rich, who have been known to refer to their president as “the monkey.” What irritates them more are his close ties to Fidel Castro, his efforts to redirect the country’s substantial oil revenues from their hands to the general welfare, and his determination to steer Venezuela onto an independent course rather than accepting the package of neo-liberal policies aggressively peddled by Washington. Chavez has even tried to organize southern nations to band together to better resist Washington’s dominant influence.

This sort of behaviour could land Chavez in serious trouble – particularly if George W. Bush is reelected. The Bush administration considers Venezuela under Chavez to be, if not a rogue state, then at least a mighty annoying one.

Chavez suspects Washington was involved in the April, 2002, coup. But he is apparently not cowed by the prospect of facing the fate of Haiti’s Jean-Bertrand Aristide, another democratically elected president who offended both the local elite and Washington. (Finding his palace surrounded by armed thugs earlier this year, Aristide discovered he had little choice but to submit his “resignation” to U.S. army personnel, who were on hand to provide him with one-way passage out of the country he had been elected to govern.)

“The Bush administration has been invaded by madness,” Chavez tells me, echoing a sentiment heard in just about every corner of the world, but rarely so openly expressed by a national leader. But, then, Chavez has a reputation for being something of a free spirit. He’s known for speaking openly and passionately, holding forth for hours at a time at public events without notes, sometimes even breaking into song. Watching him at the speaking event prior to our meeting, as he heartily belted out popular love songs for the boisterous crowd, I was struck by this unique presidential package – military man, orator, class warrior, crooner.

My interview with him stretches to two-and-a-half hours. Towards the end, an official comes in to point out that pressing matters of state await his attention. Chavez responds with a request that they bring us some ice cream. Shortly, chocolate sundaes, with cherries on top, are brought in. In between mouthfuls, we talk about the invasion of Iraq – and its relevance to Venezuela.

Like Iraq, Venezuela is rich in oil – and it has the added advantage, from Washington’s viewpoint, of being close by, not to mention being short on Islamic fundamentalists. On the other hand, it would be hard for Washington to come up with a justification for intervening in Venezuela, since it isn’t headed by a demonstrable villain like Saddam Hussein. Chavez is certainly no dictator. Indeed, dissent is amply tolerated here, as the fiercely anti-Chavez media illustrates.

Chavez believes the Bush administration invaded Iraq to get control of its oil and that it harbours similar ambitions towards Venezuela’s oil. “It’s the people around Bush, the great oil interests,” Chavez says, then in a sing-song voice, he gently chants: “Cheney, Cheney, Cheney.”