Today, Ashtanga is at the centre of the multi-billion-dollar yoga economy—one that also includes yoga methods such as Kundalini, Iyengar, and Bikram (the original hot yoga). There are hundreds of yoga studios worldwide dedicated to Jois’s gymnastic religion, plus thousands more that offer Jois-derived techniques through classes marketed with popular terms such as “Flow,” “Vinyasa,” or “Power.” Yoga practitioners are everywhere on Instagram, hashtagging with #YogaChallenge, #OneBreathAtATime, and #PracticeAndAllIsComing, feeding a workout scene hungry for connections between athletics, beauty, and self-realization. The captions speak of “openness,” “surrender,” and “purification.” But what really elevates Jois’s exercises into yoga , many practitioners believe, is the ethics one holds while practising, the purity of one’s intentions, and the philosophical view that the body is a vehicle for piety.

In the wake of recent #MeToo conversations, however, Jois’s legacy is now in crisis. The yoga guru is accused of engaging in repeated acts of sexual misconduct and sexual assault, enabled for decades by a devotional culture that saw him first and foremost as a benevolent father figure. For more than thirty years, practitioners have whispered about the intent—and nature of—Jois’s hands-on yoga adjustments, and rumours of sexual abuse have persisted long after his death. As a long-time Toronto-based practitioner and teacher of yoga, I first heard about Jois’s alleged behaviour several years ago. Over the course of a two-year investigation, I interviewed nine women across North America who all told me they were victims at the centre of the community’s dark secret: Jois assaulted his female students—in public—on a regular basis. The women describe Jois groping their breasts and humping, rubbing, or digitally penetrating their genitals under the guise of “adjusting” their postures, sometimes while pinning them down with his body weight. They’re speaking out now, in part, because of the larger reckoning around sexual assault and toxic power dynamics.

Listen to an audio version of this story

For more Walrus audio, subscribe to AMI-audio podcasts on iTunes.

Six of the women I spoke to for this article had relatively brief encounters with Jois. One studied with him in Manhattan for a week and then for three months at his modest yoga gym, or “shala,” in the Lakshmipuram neighbourhood of the city of Mysuru (which changed its name from Mysore in 2014) in southern India. Another, Karen Rain, practised the Ashtanga method for eleven years, over which she spent twenty-four months in Jois’s shala. Rain was even featured in a famous 1993 video that helped take Jois’s method global. Whether they spent days, months, or years with Jois, however, all of the women describe an environment in which the guru was permitted to freely assault his female students. Many of the women say his status outshone his abuse, allowing him to manipulate a cultural aura of spiritual authority and implied consent.

Rain described in meticulous detail the daily cycle of assault and rationalization in which she was ensnared. She told me that she quit the yoga scene entirely in 2001, exhausted by chronic pain and moral disgust. “It was all projection,” she says. “He could do what he was doing not because he was my father or uncle or doctor. It’s because he had a mystique around him.” In short, Jois may have had a particularly powerful sense of control over his students’ advancement, but he was also operating within a community that, arguably, empowered him to take advantage of students. “The whole culture,” adds Rain, “says, ‘It’s okay.’”

Modern yoga has been fraught with stories of charismatic male yoga teachers who promoted their teachings as spiritually pure and later abused, or otherwise took advantage of, students who believed their mentors were gurus or saints. In 1910, an eccentric American yogi named Pierre Bernard (a.k.a. “The Omnipotent Oom”) was tried for having “inveigled and enticed” one woman into sexual relations—the charges were later dropped, and the incident ultimately brought him infamy. Decades later, in 1983, Swami Muktananda was the subject of an article that chronicled sexual activities he was alleged to have had with young female students; a New Yorker story later reported that at least 100 people believed the allegations to be true but were afraid of being ostracized by the community. That same decade, Yogi Bhajan’s 3HO Foundation, commonly called the “Happy, Healthy, and Holy Organization,” settled several assault lawsuits against its leader, including one case of rape and confinement brought by a woman who entered his circle at age eleven.

In 1991, Swami Satchidananda, who opened Woodstock by leading the crowd in a chant of “Hari Om,” was the focus of protest after allegations of sexual misconduct against female students surfaced; he was never charged and died a decade after the allegations were brought forward. In 1994, “Meditation in Motion” innovator Amrit Desai was removed as spiritual director of the Kripalu Center in western Massachusetts over allegations of abuse of authority and sexual misconduct. That same year, a student sued another prominent yoga guru, Swami Rama, for sexual misconduct; after his death, a jury awarded her almost $2 million, in 1997.

It goes on. In 2012, John Friend, who is a student of both Swami Muktananda and Jois’s main rival, B. K. S. Iyengar, stepped down from his All-American Anusara Yoga brand after allegations surfaced that he had been sleeping with his female students—renewing a conversation within the yoga community about power dynamics and ethical guidelines. In 2016, “hot yoga” pioneer Bikram Choudhury abandoned a fleet of luxury cars and fled his home in California, facing $6.5 million in damages owed in a sexual-harassment lawsuit; a judge later issued a warrant. Separately, Choudhury is facing six lawsuits alleging sexual assault and sexual harassment. (His current whereabouts are unknown, and there is still a warrant out for his arrest.)

As the #MeToo movement hits the yoga scene, women are coming forward on social media, forcing crucial questions into the spotlight that the entire industry must now confront: Is the yoga studio consistently the healing space it is advertised to be? Or has it engendered a culture in which spiritual surrender can be conflated with physical submission? Above all, practitioners must now ask how a culture with such a robust history of abuse has also been marketed as a path to bodily autonomy, spiritual awakening, and a cure-all for both mental and physical ailments.

Meanwhile, the stories keep coming. In November 2017, Rachel Brathen, who is based in Aruba and known as “Yoga Girl” to her 2.1 million followers on Instagram, posted a general call for #MeToo stories of abuse within the yoga industry. “I’ve received 200-plus accounts of abuse, but the emails keep coming in,” she told me in an email. “Almost all are sexual abuse, harassment or rape. Thirty-plus male teachers mentioned, but many are writing in anonymously. It’s everywhere.”

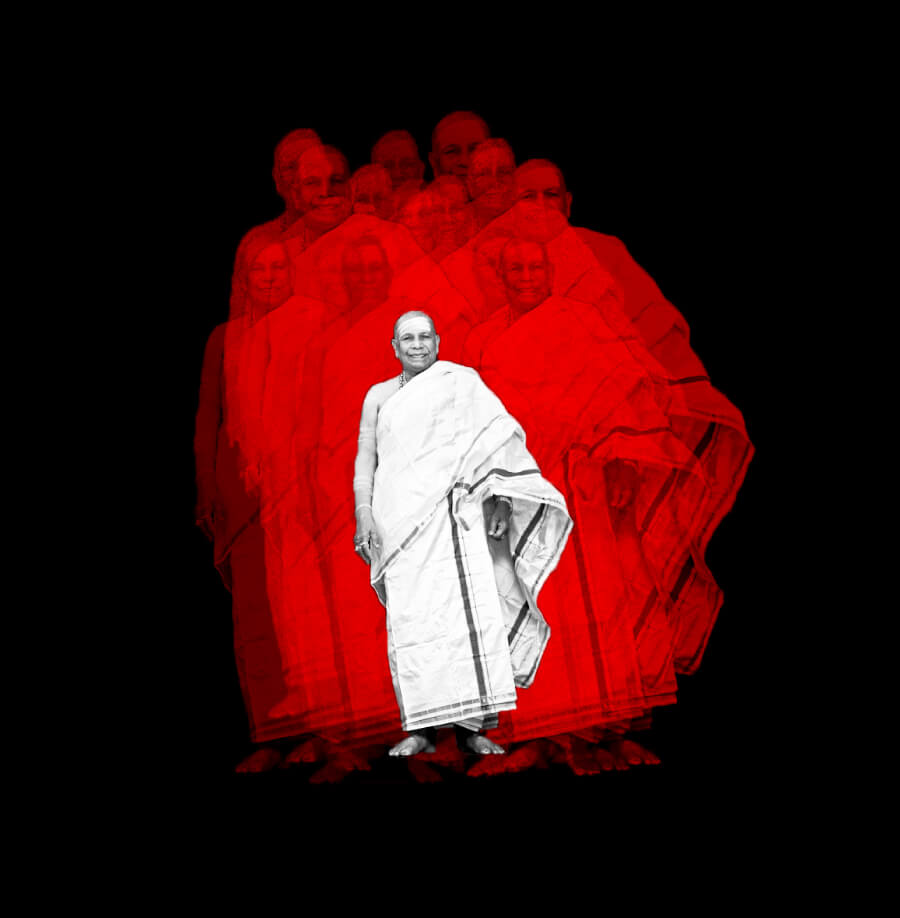

T here are haunting photographs of the formerly svelte Jois from earlier in his life, when he was under the brutal tutelage of Tirumalai Krishnamacharya, a key figure in the modern yoga movement. Jois once had the build of a lightweight boxer and an intense thousand-yard stare. But by the time the first waves of Western seekers started to find his Mysuru shala in India in the late 1960s, Jois resembled a rotund, puckish grandfather. He taught at the local Sanskrit college in Mysuru, where he was also head of the yoga department until his retirement in 1973. Jois preached a strict and exacting yoga work ethic that resonated with bohemian Westerners who longed for a disciplined, hands-on spirituality. “Ninety-nine percent practice, 1 percent theory,” Jois would intone.

He seemed a perfect screen for the projections of prodigal Westerners who longed after the spirit of another age. While Jois taught physical yoga, many of his students also sought an education in surrender and transcendence. Jois obliged, resurrecting the harsh lessons learned in his youth. He quickly became known as a taskmaster who not only sequenced his postures with precision but also manhandled students’ bodies into contorted knots—ostensibly to help them further their practice and, ultimately, achieve serenity.

In 1975, Jois embarked on what became the first of regular teaching tours abroad. (He’s alleged to have assaulted women both on his trips to North America and during their trips to practise at his Mysuru shala.) By the 1990s, core devotees who met Jois and followed him on tour or back to India were selling his exacting choreography on VHS tapes. The students in the video sport the prototypes of current yoga wear and perform a perfect balance of strength and flexibility. The narrative, then and now, was that yoga gives shape to devotees’ lives as much as their bodies. It has the potential to pull people up out of purposelessness, depression, and addiction. It may even heal their physical injuries and illnesses. For students at dedicated Ashtanga studios, the practice convenes a community before dawn, six days a week.

But it’s hard to square the miracle stories with the unvarnished video and pictures that survive Jois. In clip after clip, he stands on the limbs of both men and women as they sink excruciatingly into poses. He wrestles women’s legs behind their heads and presses down on them, groin to groin, as they lie back and stare at the ceiling. Or he lies down on top of them, his nude belly to their backs as they squish into seated forward folds. Some photographs challenge the notion that Jois was “adjusting” students at all. One, taken in the late ’70s or early ’80s, shows Jois draping himself over a woman who is lying on her back. He’s flattening her extended leg to the floor as he presses her other leg out to the side. He uses his free hand to grope her breast. He gazes at her closed eyes with something halfway between serenity and a smirk.

There is almost no historical evidence for yoga teachers physically adjusting their students prior to the 1930s “Mysore Asana Revival”—as yoga scholar Mark Singleton dubs it. At that time, as Singleton contends in his 2010 book, Yoga Body , gymnastics training transformed a practice that had long been taught through oral instruction into a modern form of Indian group exercise for boys. Jois’s American and European students, however, believed his adjustments to be “traditional” and essential to his magic. They and their own students have gone on to normalize these interventions—even when intrusive, forceful, or painful—as a common feature of the yoga mainstream.

The widespread imitation of Jois and other Indian teachers, such as B. K. S. Iyengar, has fostered the implicit expectation among some that a yoga master should know students’ bodies better than they do and that discipline and sometimes pain were necessary to further their practice. One result of this mindset is a culture in which a prominent book on yoga adjustments contains neither the words “consent” nor “permission” within its 184 pages. Yoga Assists was written by the founders of Manhattan’s Jivamukti Yoga School, a key institution in making the Jois method fashionable worldwide.

It’s now worth asking whether the encouragement to submit to physical intrusion and pain through adjustments disarmed resistance to sexual abuse. Katchie Ananda was thirty-five and living in Boulder, Colorado, when she encountered Jois at a yoga intensive held there in 2000. She told me about being both physically and sexually assaulted by Jois over the span of several days. In one encounter, she says, Jois wrestled her into a deeper standing back bend than she was ready for. Her hands were on her ankles—already an extreme position. Jois moved her hands sharply up to behind her knees until she heard an internal rip. Later, an MRI showed a disc herniation, to which she believes Jois contributed.

During that same event, Jois leaned into her and pressed his groin directly onto hers while she was on her back with both legs behind her head. “I remember registering that this was wrong,” she wrote in a public Facebook post. “But I was also completely absorbed in the sensation of having my hips opened, probably past what they could handle.” Charlotte Clews’s experience at an event in Boulder followed the same arc. At twenty-seven, Clews was living in Boulder and felt she’d found a home in the yoga community’s athleticism and was progressing toward the most demanding postures. During one practice, Jois tore her hamstring attachment as he stood on her thighs and pushed her torso into a deep forward fold, with her legs open in a wide V. She persisted through the pain until Jois again approached her to hold her steady as she bent over backwards into a series of “drop backs.” He pressed his groin directly against hers as he supported her as she arched up and down. She had never been touched in that way in that posture before.

Clews tells me that she was trained to believe that pain in practice was irrelevant and that injury was a risk in Ashtanga. But part of her also believed that a “good” student—who properly submitted to the teacher—would not get hurt. The group considered it to be a special honour when Jois assisted them. Clews remembers no impulse to tell her friends about the pain she was in, nor to resist Jois, in part because he was supporting her lumbar spine, which made resistance nearly physically impossible. She says Jois later insisted that she fold her right leg in lotus position despite her ankle being sprained. When she didn’t comply, she says, he aggressively torqued her legs into position and badly reinjured the ankle. It didn’t occur to Clews at the time to blame Jois for the pain, she says. She felt she was choosing the experience.

I n November 2017 , Karen Rain published a #MeToo statement to her Facebook page. She described being regularly assaulted by Jois between 1994 and 1998. Like other women I spoke with, Rain says that Jois assaulted her when he was adjusting her. In her case, the assaults occurred in various postures, including one in which she was lying on her back with one of her legs pulled up straight alongside her body and with her foot over her head. “He would get on top of me,” she says, “as he did with many women, in the attempt to push our foot down over our head, and he would basically hump me at the same time.”

Other women describe similar instances in his classes, with presumably similar tactics—using the opportunity to adjust women as an alleged means of assault. Marisa Sullivan remembers sitting on the stairs outside the open door of Jois’s shala on her first day in Mysuru in 1997 and seeing him put his hand on a woman’s buttock and stare off blankly into space. She watched, aghast, as he kept pawing the women. As the days stretched into weeks, she commiserated with two other American students who were also appalled. When it was her turn to practise in the room, she was hypervigilant, trying to time her postures to avoid vulnerable positions whenever Jois passed. When he did touch her, she froze.

But she had also prepared for years for this opportunity, had come a long way from New York City, where she lived, and felt socially invested. “I feared my position in the community if I spoke out,” Sullivan says. “But much more than that—I had lived through sexual abuse at home and my truth was denied. I did not want anyone taking away my truth that the way I and other women were being touched was wrong. I heard too many devotees support Jois’s actions with varying excuses.” She made a choice to stay. “I said, ‘I’m here. I’m just going to dive in. Enough with this questioning.’ I’d always been on the outside of communities.”

After that moment, she began to let Jois physically adjust her. Suddenly, he began showering Sullivan with attention. She felt that she blossomed. Soon, she would either kiss his feet or bow down at the end of each session. But, a few weeks later, he assaulted her while she was standing in a forward bend, her legs spread wide and her arms raised up and over with her hands reaching toward the floor. First, he pushed her hands to the floor, which she found agonizing. In that position, she was immobilized. Suddenly, she says, Jois walked his fingers over her buttocks, landing on her groin, where he began to move his fingers back and forth over her leotard.

Hawaii-based Michaelle Edwards describes a similar incident that took place in 1990 at an event with Jois on the island of Maui. Edwards was in Paschimottanasana (an intense seated forward fold) when Jois laid down on top of her, pushing her deeper until she could barely breathe. He then reached underneath her hips to use his fingers to grope her. “I was shocked and thought maybe he was confused about what he was doing,” she says. “And then I really felt molested and very uncomfortable to have his weight on me.” Edwards told Jois “no” repeatedly. Then she tried to move him off of her. Finally, she was able to stand, only to see Jois smiling. “He began to call me a ‘bad, bad lady.’” At the end of the class, she saw people treating him “as though he was some kind of deity or enlightened being.”

Jois’s status made it hard for many women to feel as if they could come forward about their assault. In 2000, says Anneke Lucas, Jois sexually assaulted her during a yoga intensive in the ballroom of the old Puck Building in downtown Manhattan. Lucas, a New York City–based writer and now the executive director of a non-profit, had come to Ashtanga practice as part of her path to healing after surviving sex trafficking as a child. Jois groped her a few days into the workshop. “I sensed that if I were to respond in public, he would have experienced the humiliation he’d just made me feel. He would be angry, and send me off,” Lucas wrote in an article first published on a prominent New York yoga website in 2010 and reissued in 2016. “I thought I might be banned from my community that had come to feel like home. I felt confused, felt helpless, and held my tongue.” In the article, she describes how she later confronted Jois about his actions, writing that she asked him, “‘Guruji, why you no respect women?’”

For other women, it could be difficult to reconcile Jois’s touch, which was so often characterized as a spiritual payoff, with the reality of the abuse. Michelle Bouvier told me that Jois groped her groin twice at a 2002 event in Encinitas, California. Then twenty-four years old, she remembers at first being shocked and then trying to ignore him by syncing up her energy with that of the older woman beside her. “I thought, ‘This is not really real anymore,’” Bouvier tells me. “[But] if I had thought there was anything spiritual about this scene, that feeling was gone.”

At least one other woman chose to confront Jois directly. Maya Hammer visited Jois’s Mysuru shala in the late ’90s, at the same time as Sullivan (the two later travelled together). She was twenty-three at the time and living in Kingston, Ontario. Early into her practice at the shala, Jois groped Hammer’s breast. At first, she thought it might have been an accident. By the third day, he was leaning forward into her buttocks and groin region. She was shocked. After a call home to her father, Hammer set out to confront Jois. She told me that he denied groping her, then promised that he wouldn’t keep doing it, and then waffled when she demanded a refund. She stood her ground until he reluctantly fetched $200 in cash from the back room and thrust it at her. She left the shala soon after.

It wasn’t the only time Jois was confronted. At another event, in 2002, Micki Evslin, who was then fifty-five, attended an event with Jois in Hawaii, where she lives, as part of his American tour that year. Evslin remembers being excited by the prospect of meeting the master. She was in a standing forward fold when she saw Jois’s feet approach from behind. He then penetrated her vagina with his fingers. “He had to use a lot of force,” says Evslin, in order to stretch the fabric of her clothing. Before she could react, Jois moved on down the line of bent-over practitioners.

Jois’s host for the Hawaii event asked not to be identified but did tell me about the incident. After hearing about the behaviour that was taking place in class, the host intervened by calling a meeting with Jois, his daughter, Saraswathi Rangaswamy, and his grandson, Sharath Rangaswamy (who’s known more commonly as Sharath Jois). Saraswathi and Sharath often travelled with Jois and are now the lead teachers of his shala in Mysuru, now called the K. Pattabhi Jois Ashtanga Yoga Institute. Today, the Ashtanga community calls Sharath “Paramaguru,” a name that implies he now holds his grandfather’s “lineage”—a putative combination of ancient techniques and inherited authority. “It was not my intention to shame him,” the host wrote in an email, referring to Jois. “But to delicately inform him that in the West, such behavior could result in a law suit.”

The host writes that Saraswathi interjected: “‘Not just the West, but anywhere!’” Sharath, the host adds, then said that if Jois continued such behaviour, he would not teach with his grandfather anymore. (The Walrus has reached out to Sharath multiple times about these allegations and his response to them. He has yet to comment.) Up until then, it had been an accepted practice for Jois to squeeze the buttocks of women who lined up to greet him after every class and kiss them on the lips. According to the host, this behaviour stopped after that confrontation and Sharath and Saraswathi no longer allowed Jois to say goodbye to practitioners at the end of class.

I n over two years of investigating, I haven’t encountered or heard of a single senior student who publicly confronted Jois or who issued a public statement about the assaults during his lifetime. On the contrary, until recently, the community has been largely silent. Among students who are now able to acknowledge his behaviour, some say it was isolated, that it died with him, and that, on the whole, Jois’s practice has enlivened and empowered countless people.

Six of the women in this story have stayed in the yoga industry, working quietly to heal the power dynamics they endured. Lucas trains yoga teachers in trauma sensitivity before sending them to teach at Rikers Island under the banner of her non-profit organization, Liberation Prison Yoga. Sullivan now teaches chair yoga to cancer patients in dementia nursing homes, seniors’ centres, and homes for the mentally ill. She also leads yoga-inspired workshops celebrating women’s sexuality. Edwards has become an advocate for safety and agency in the yoga industry. She has innovated a theory of movement she says is rooted in evidenced-based biomechanics and which she hopes will mitigate a rising tide of yoga injuries. She advocates against the authoritarian teaching methods of the past. “My experience of Jois and the abuse,” says Edwards, “actually helped propel me in a different direction with yoga and bodywork. It was a springboard to find something that originated from within, rather than from teachers who sought control over their students in ways that did not feel safe, spiritual, kind, or compassionate.”

Maya Hammer now works as a certified psychologist. Evslin still practises a personalized version of Ashtanga at home but only attends the occasional class. Michelle Bouvier, Katchie Ananda, and Charlotte Clews still teach yoga, but in a post-Ashtanga, feminism-informed mode.

Rain, however, has happily left yoga behind. Over the years, she’s healed her yoga-related chronic pain through physical therapy. She healed her spirit, she says, through dance. She now works as a Spanish interpreter and educational assistant, often with undocumented Latino children at a local public school. She’s been trained as a mandated reporter for suspected child sexual abuse and has emerged as a powerful advocate for restorative justice within the community she fled so long ago.

For Rain, one of the most disturbing features of her recovery has been to come to peace with her own participation in the “illusion,” as she calls it, that there was something spiritual about the postures or the man who taught them. “The Ashtanga yoga I knew was sanctioned physical and sexual abuse,” says Rain. “People thought yoga postures were spiritual, and they were seeking something through them. Those two things combined helped maintain the fantasy about Jois.”

Rain’s willingness to challenge that fantasy has sent shockwaves around the world. Responses to her allegations, which were first made on social media and her blog , have been fraught and polarized. On dozens of comment threads, people debate why Jois’s alleged behaviour wasn’t addressed while he was alive and lament that his family members are the ones who have to deal with the repercussions. Others defend Rain, try to educate each other about rape culture, express grief and betrayal, or wonder whether it all matters today. A petition is circulating online, asking Sharath to issue a statement that acknowledges his grandfather’s abuse.

Rain has argued for Jois’s portrait and all feel-good images of him to be removed from yoga altars and websites. She wants people to reconsider using the honorific “Guruji” when referring to Jois. Beyond this, Rain has also called for those who may have witnessed Jois’s alleged abuse to testify to it, so that those who’ve come forward can feel safer and more visible.

Sharath Jois has not yet responded to Rain or the petition. He has, however, issued a new code of conduct for Ashtanga teachers that they have to follow to stay authorized by the institute in Mysuru. One new stipulation demands that teachers provide “an environment free from sexual harassment”—at the same time, it offers little guidance on how to create such an environment nor does it offer a possible accountability process for those who might violate it.

A few Ashtanga teachers are trying to imagine a progressive way forward for their beloved method. Greg Nardi, who runs an Ashtanga school in Fort Lauderdale, Florida, with his husband, has spoken out passionately against the knee-jerk response to defend Jois instead of his victims. “Many well-intentioned and good people were complicit in upholding a harmful power structure,” Nardi posted publicly to his followers on Facebook. “It is an imbalanced power structure that allows men to live blind to the harm that they perpetrate and that prevents them from being held accountable. Many dogmas surrounding Yoga pedagogy need to be revised including the belief in methods and gurus as infallible, and the subsequent emphasis on submission rather than intuition and reasoning.”

Jean Byrne, a yoga scholar and long-time Jois student who runs three Ashtanga studios in Perth, Australia, announced in a public post on Facebook that she was removing Jois’s portrait from their practice spaces and instituting the use of “consent cards,” by which students can silently indicate their permission to be touched. For a culture where adjustments have been accepted as part of the practice for decades, this is truly revolutionary.

What will replace the portrait of Jois on the altars of yoga studios around the world? Ashtanga practitioner Dimi Currey offers a restorative idea. She never met Jois. She’s practised in Vermont since 2012 and says that Ashtanga helped her recover from an abusive relationship. Currey argues on Facebook that Ashtanga exists today as much because of the silencing of Jois’s victims as it does through his students’ evangelism. The method might not have spread if the truth about its founder hadn’t been covered up. “Maybe instead of Jois’s picture in studios, on altars,” Currey says, “maybe it is [the victims’] pictures that belong there.”

If you have information on this story, Keybase is a secure and anonymous way to reach the writer, Matthew Remski . You can also share information with our digital editor, Lauren McKeon .

April 25, 2018, 6:17 p.m.: A previous version of this article incorrectly stated that the majority of assaults experienced by Karen Rain occurred in a posture in which her big toe was hooked with her finger over her head. In fact, the assaults occurred in various postures, including one in which she held her foot over her head.

Update, April 30, 10:17 a.m.: This article has been updated to reflect that Anneke Lucas says she confronted Jois about his alleged behaviour shortly after it occurred.