DC Comics

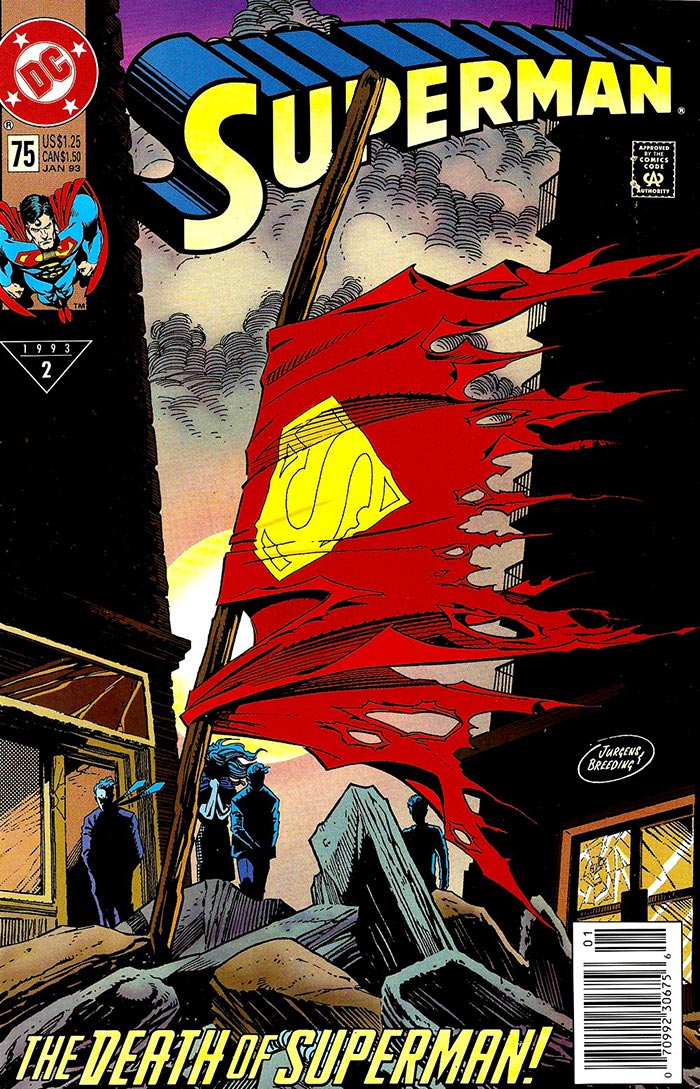

DC ComicsIn January 1993, waiting in line at Lawtons Drugs, I begged my mom to buy me a copy of Superman Vol. 2, No. 75. She was well aware of its storyline, which had made the evening news: Superman was dead, killed in a brutal duel with an alien villain named Doomsday. She took one look at the now-iconic cover, with Superman’s tattered cape tied to a stake like a flag at half mast, and flatly refused.

“Too violent,” she said.

I was only six years old, after all.

Of course, Superman wasn’t actually dead. DC Comics’ writers soon brought him back to complete the three-part arc, later collected as The Death of Superman, World Without a Superman, and The Return of Superman. With more than six million copies printed, Superman 75’s record for largest single-day sales for a comic book was the industry’s swan song for print. However, in many ways, Superman was dead—or at least his relevance was.

Superman’s battle with Doomsday was the last time when Earth’s favourite Kryptonian really held the zeitgeist. While mere mortal characters like Batman and Iron Man have found great success by being reborn in the multiplex, the comic industry’s first titan has been left in their dust.

Sure, the Man of Tomorrow has remained viable on the small screen. There was the cringe-worthy Lois and Clark (1993–1997), with Terri Hatcher and Dean Cain, as well as the teeny-bopper Smallville (2001–2011). And, while comic sales have dwindled in recent years, Supes has nonetheless enjoyed critical success with stories such as Red Son (which reimagines him as a Soviet hero) and Kingdom Come (in which he returns after a ten-year absence to tackle a new class of rogue superheroes).

But nothing in Superman’s twenty-first-century life has seized the public’s attention the way that The Avengers and The Dark Knight films have. The blockbuster movie is our culture’s mega event. Print and television exposure pales in comparison.

Superheroes have become a boon for the Hollywood film industry. In the last five years alone, four superhero movies have made over a billion dollars at the box office: The Avengers ($1.5 billion), Iron Man 3 ($1.2 billion), The Dark Knight Rises ($1.1 billion), and The Dark Knight ($1 billion). Superman, conversely, has failed to make the same leap.

Superman’s modern irrelevance is noteworthy because of the character’s historic role as the comic industry’s greatest conquistador of new media. In decades past, Supes—depicted by talents such as Bud Collyer, George Reeves, and Christopher Reeve—carried comics out of pulp and into radio, television, and film.

In 2005, Christopher Nolan resurrected the once-exhausted Batman series with Batman Begins. The following year, it seemed a no-brainer that Superman would once again reign atop the industry, when Bryan Singer, director of X-Men and X2, made Superman Returns. Not so. The film failed to excite fans and barely broke even at the box office.

Superman Returns’ first mistake was that it didn’t properly reintroduce the character. Singer tried to short-circuit the typical franchise reboot. His film’s plot confusingly picked up where Reeve’s Superman II (1980) left off, ignoring III (1983) and IV (1987).

But this doesn’t get to the larger problem, which is how poorly Superman resonates with contemporary audiences. Victory comes too easily for the last son of Krypton. Modern Moviegoers find it easier to relate to a Batman who hides blood, sweat, and tears beneath his cowl, than a Superman who can bounce a bullet off his eyeball.

Things weren’t always so. There’s a very good reason why so many Seinfeld episodes have Man of Steel Easter eggs. Superman has endured for over seventy-five years because he is the archetypal North American hero. His is the ultimate orphan narrative, which resonates with our shared desire and struggle for authenticity in the face of conformity and alienation.

Superman first came on the scene in 1938 with Action Comics No. 1, but his origins reach back into the ’20s. He was created by Jerry Siegel and Joe Shuster, first-generation Jewish immigrants. Much like Superman’s father, Jor-El, sent his only son from the imminently doomed Krypton to Earth, the Siegels and Shusters had escaped the increasingly anti-Semitic Europe for North America.

Shuster grew up in Toronto, where he worked as a paperboy for the Toronto Star, which would later be the inspiration of the Daily Planet, Metropolis’s daily newspaper. His family was desperately poor, and couldn’t afford to nurture his nascent artistic abilities. Undaunted, he sketched on discarded rolls of wallpaper.

Eventually, Shuster’s father gave up on his failing business and moved the family to Cleveland. Joe was nine years old. In Cleveland, he met Jerry Siegel, and together they created the character.

Superman is a manifestation of the Jewish experience in North America. Originally named Kal-El, he adopts the waspy alias Clark Kent, and hides his true identity behind a middle American visage, so as not to alienate his adopted home. As Quentin Tarantino points out in Kill Bill 2, Superman reverses the traditional superhero binary, making the day-to-day Kent persona his secret identity, while Superman is the real Kal-El.

Nonetheless, while this reversal makes Superman distinctive, it also represents a disconnection between generations of superhero fans. We cannot suspend our disbelief enough to accept that when Kal-El throws on a pair of glasses, everyone—including Pulitzer Prize–winning investigative reporter Lois Lane—sees Clark Kent. And the glasses are just the tip of the iceberg when it comes to Supe’s limitations as a character. His herculean abilities make him unsuitable for today’s problems. (Consider the hunt for Osama bin Laden in Kal-El’s world. He can fly at Mach speeds, see through walls, and hear any sound. The search would have taken minutes, not years.)

Superman has dealt with problems like these before. During World War II, for example, DC’s writers had to address the concern as to why Superman didn’t just fly to Europe and zap the Wehrmacht with his eyebeams. Instead, he focused on the homefront, battling street gangs and Lex Luthor’s corporatism.

Unfortunately, such plotlines are much better suited for a character like Batman, whose vulnerabilities feel more real to us. Moreover, almost any story that attempts to make Superman vulnerable relies on kryptonite, comics’ most used and abused plot device.

Undaunted by these challenges, Supes is back in the blue and red spandex with a new movie currently in theatres. Man of Steel is directed by Zack Snyder, who made 300 and Watchmen, and is produced by The Dark Knight’s Nolan. The movie takes us back to Krypton and on to Kansas, where we follow Kal-El as he becomes Clark Kent and ultimately Superman.

In keeping with Superman’s mythology, Clark’s adoptive family teaches him to conceal his identity. Nonetheless, he feels compelled to use his powers to help people. General Zod, a Kryptonian war criminal previously depicted by Terence Stamp in Superman II, arrives to threaten Earth’s fate, following the standard supervillain manual. Superman springs into action, destroying a huge swath of the world to save the rest.

Impressively, Man of Steel grossed over $116 million on its opening weekend, besting Toy Story 3’s previous record for a June opening. However, Superman’s box office gross fell 65 percent the following weekend, a colossal drop off. Such a top-heavy reaction confirms the franchise’s hollow cachet.

Consequently, insofar as the zeitgeist is concerned, the Man of Tomorrow is a has-been, a nostalgic brand to be bought and sold, not a rewarding character with new depths to explore. Superman is still dead, making Man of Steel the most-expensive and, briefly, most-watched funeral of our time.