On a chilly afternoon last autumn, I padded down a faint path beneath a grove of hemlock trees in British Columbia’s inland temperate rainforest. The moss on the ground was as thick as a mattress. Above, grey-green beards of lichen hung from the branches. Located along the province’s eastern flank, bordering Alberta, the inland rainforest gets much less attention from environmental groups than BC’s coastal rainforests, where activist blockades of old-growth tracts regularly make the news. But cold-climate inland rainforests are even rarer ecosystems.

Listen to an audio version of this story

For more audio from The Walrus, subscribe to AMI-audio podcasts on iTunes.

The older the forest, the more lichen it has, explained my guide, Michelle Connolly, an ecologist who recites their names like poetry: peppered moon, netted specklebelly, pink dimple, cryptic paw. New species continue to be discovered here, making this forest among the most lichen-diverse places on the planet. As we walked, she described the area’s remaining ancient cedars, which grow up to four metres in diameter and can be close to 2,000 years old. The inland rainforest is also home to around 2,400 plant species, many of them rare, and wildlife such as wolves, wolverines, and southern mountain caribou.

But this patch of forest is also under threat. In 2021, Connolly co-authored a peer-reviewed study that found that BC’s inland rainforest—which once totalled over 1.3 million hectares—was endangered, according to International Union for Conservation of Nature criteria, and could experience ecological collapse within a decade if current logging rates continue. The study found that 95 percent of its core habitat, forest located more than 100 metres from a road, had been lost since 1970. “We’re fighting over the last pieces,” Connolly says.

Historically, lumber and pulp mills processed most of the wood harvested in BC, but Connolly is battling with a newer, rapidly growing global industry: wood pellets. Roughly the size and shape of cigarette filters, wood pellets—also referred to as biomass—have long been a niche fuel for wood-burning stoves, furnaces, and boilers. But demand from overseas electricity plants, which can switch from burning coal to burning pellets with relative ease, has driven a dramatic expansion: from less than 2 million tonnes of production globally at the turn of the millennium to around 60 million in 2018. A $9 billion global industry, according to a 2020 estimate by a US research firm, the pellet market is expected to double again in the next five years. European power plants have been among the biggest consumers—pellet-fired power plants are uncommon in North America—but demand from Japan and South Korea has also increased in recent years.

The Wood Pellet Association of Canada claims that BC’s forests produce more pellets than anywhere else in the world. Prince George, a town about a ten-hour drive north of Vancouver, sits at the industry’s epicentre. It’s also Connolly’s home base. By day, she’s a project manager at a charity called Ecotrust Canada, but on the side, Connolly, forty-three, runs Conservation North, a tiny volunteer environmental group that has become something of a mosquito in the ear of local pellet companies.

Connolly doesn’t stand alone. The pellet industry has faced a global backlash over its claims that burning wood, unlike coal and other fossil fuels, is “carbon neutral” and helps arrest climate change. The pro-pellet logic: if new trees are planted to replace those that are cut, as is required in BC, the emissions will be cancelled out as the new trees sequester the carbon released when the pellets were burned. The Paris Climate Agreement supports this rationale, excluding burned wood from a country’s carbon budget as long as the forests are replanted.

Critics, however, say this science is completely faulty. A forest of saplings may take a century or more to mature into an ecosystem that holds as much carbon as the one it replaced. An open letter from 500-plus scientists and economists sent last year to world leaders warned that burning pellets “is likely to add two to three times as much carbon to the air as using fossil fuels.” Nearly 800 scientists and academics, including two Nobel laureates and three winners of the US National Medal of Science, signed a similar letter in 2018. “The whole thing boils down to the obvious fact that burning things emits carbon quickly and regrowing things to sequester carbon takes a long time,” says Mary Booth, director of the Partnership for Policy Integrity, a US-based environmental nonprofit critical of the pellet industry. In other words, climate change will have wreaked havoc long before those young trees mature into an ecosystem that holds as much carbon as the one they replaced.

“BC has nuked so much of our forests that everything remaining in a natural state at this point is really important,” Connolly says. “The pellet industry has the capacity to obliterate what’s left”—a trajectory she intends to stop.

The pellet industry makes a number of green boasts, chief among them that pellets are a sustainable by-product of forests already being cut. This claim is based on the fact that pellets can be made from lumber waste, such as sawdust and slash (larger debris left by logging). In the early days of pellet production, lumber waste was indeed the principal raw material, but Conservation North, which keeps tabs on local plants, has found that whole trees increasingly feed the industry.

To demonstrate, Connolly invited me along to visit the Pacific BioEnergy plant in Prince George. The company has since closed permanently: rising operating costs forced it to sell its contracts to Pinnacle Renewable Energy, a nearby competitor. But, at the time, as the second-largest pellet producer in BC, it was Exhibit A in Connolly’s argument that pellet companies tend to consider any tree for which they don’t have a use “waste,” even if it’s still in the ground. Wearing black combat boots, Connolly clambered up an earthen bank to inspect an enormous pile of logs at the facility. She slid her hand across the cut ends as she walked along the pile, noting the species—the peeling white bark of birch, the stringy red bark of cedar, the rough brown bark of Douglas fir—and their diameters. Most trees were under a foot thick, but some were much larger. She stooped to count the rings on the biggest one: it was more than 200 years old. This, for Connolly, was clearly not slash. “The industry hides what they’re doing with obfuscating language about waste and forestry residuals,” says Connolly.

Pacific BioEnergy did not respond to repeated interview requests, but its website acknowledges the use of whole trees as feedstock, or raw material, while seemingly downplaying their role: the company claims to use only “low-grade timber that has no other economic value,” which generally refers to trees unsuited for lumber or that have been damaged by fire, rot, or insects. Still, such trees have tremendous ecological value. “Bark beetle outbreaks and wildfires are normal, natural disturbances, part of how forests rejuvenate themselves,” says Connolly, citing evidence that “disturbed forests are actually even more important for some wildlife” than undisturbed ones. And so-called low-grade trees still capture plenty of carbon.

Pacific BioEnergy marketing materials depict a virtuous loop of carbon-sequestering trees, forestry by-products, and power production. But audits by the Sustainable Biomass Program, a third-party certifier, reveal a different story: that the company’s use of whole logs ballooned from 6 percent of its feedstock in 2019 to nearly 50 percent in 2020. Satellite imagery of the site from Living Atlas of the World, a geographic image database, appears to reflect a rapid shift away from waste-based pellets. The only feedstock visible at the Pacific BioEnergy site in a 2015 image are lumber residuals—as waste materials are known in industry parlance. In a 2018 image, logs cover an area roughly equal to that of residuals; in an April 2021 Google image, log piles spread across the equivalent of four soccer fields surrounding the plant, roughly six times the area of residuals.

In the forest I visited with Connolly, we saw orange flagging tape printed with “Pacific BioEnergy” tied around some stands of trees, identifying them as a future logging site. When Conservation North first discovered this, in 2020, Connolly went on the evening news. She referred to the forest as “old growth.” John Stirling, at the time Pacific BioEnergy’s CEO, countered that assessment on air: “We are not clear-cutting in old-growth forest!”

He was technically right. In BC’s drier landscapes, trees more than 140 years old meet the provincial definition for old growth, but Connolly says that, in the rainforest, old growth is defined as more than 250 years old. Like the logs she found at the Pacific BioEnergy plant, the trees in the tract were just a few decades shy of the official threshold, but Connolly tells me that’s beside the point. “To an ecologist like me, it was old growth. But, even by the strict forester’s definition, it’s future old growth.”

Connolly claims that, after the news segment ran, Stirling told her they would consider preserving the tract. (Stirling did not respond to multiple requests for comment.) They were, she says, on cordial terms as a result—Pacific BioEnergy seemed open to finding more sustainable sources for pellets, including focusing on suitable secondary forests that have either been replanted or have regrown naturally after being cut. But, according to Connolly, things soured when the company’s workers saw us inspecting their log pile. As we pulled out in her pickup to leave, Stirling screeched up in his, blocking our exit. He was livid.

“Now I see how you operate, Michelle,” he said. “This is not okay.”

“You’re right, John. I’m sorry,” said Connolly, who regularly inspects log piles at plants and on forest roads in the area. “I’ll ask for permission first next time.”

“I don’t think you’ll get it,” said Stirling.

An aerial view of industrially logged primary forest in the inland rainforest. Video courtesy of Conservation North

Connolly has cropped hair and a no-nonsense bearing. She grew up in the suburbs of Vancouver and, in 2011, came to Prince George to attend graduate school at the University of Northern British Columbia, where she earned a degree in environmental studies. She fell in love with the inland rainforest—and a wildlife biologist—and plans to settle on a small homestead outside this town of 80,000.

Prince George is the hub of a sparsely populated region, a place where the acrid aroma of smouldering slash piles lingers in the air, where lots on the outskirts of town are stacked with freshly milled two-by-fours and telephone poles, ready for export. Mr. PG, a famous eight-metre-tall wooden statue of a lumberjack with a Pinocchio-like nose made of a log, looms over a main intersection. But the economy is shifting. Even with the steep rise in lumber prices, mills have steadily shuttered over the past couple of decades. Since 2000, BC has lost around 50,000 forestry jobs, about half of the provincial sector. Lumber production in the province has declined in recent years, and while lumber’s export value remains more than ten times that of pellets, biomass is ascendant.

There’s not much of an environmental movement in Prince George outside of Conservation North, which is run out of Connolly’s home. The four-woman operation has organized small rallies in town. As often as possible, the crew piles into a four-wheel-drive truck to scour the logging roads that branch like mycelia from Prince George.

One Saturday, we drove to meet a local trapper who often supplies the group with tips about where logging is taking place. His traplines once netted around 200 martens, a type of weasel with valuable fur, each year, but as a result of habitat loss from logging, “now I’m lucky to catch twenty,” he says. “We can only trap where the habitat produces extra animals. If we started trapping base populations, we would be out of business.”

Despite the clear-cuts we passed, the mood was light. At one point, there was an extensive conversation about the importance not of living trees but of the fallen ones that accumulate in mature forests and serve as habitats. “We’re obsessed with dead trees and members of the weasel family,” joked Jenn Matthews, Conservation North’s former outreach coordinator.

Connolly can come across as a polite ecology nerd, but her end goal for the forestry industry may sound radical even to some environmentalists. She wants to put an end to all logging of BC forests not yet disturbed by industrial activity—primary forests, ecologists call them—and restrict future logging to secondary forests. As we drive, the scenery alternates between barren clear-cuts and strikingly uniform secondary forests. Doused with herbicides that prevent less-desirable broadleaf species from taking hold, these areas are left to regenerate for a few decades before being harvested. She believes the ecological value of primary forests accrues over millennia—they not only provide richer wildlife habitats than secondary forests but can store between 50 and 60 percent more carbon. “Primary forests are nonrenewable by definition—they don’t come back,” says Connolly. “So what we’re proposing is pretty reasonable.”

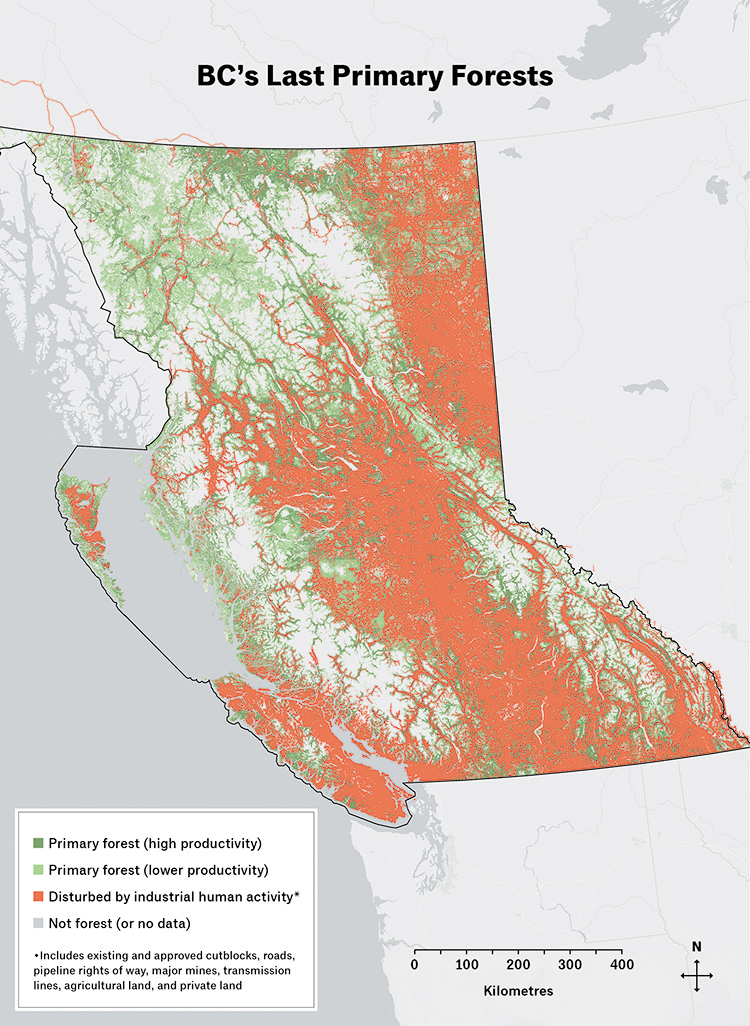

Unable to find a catalogue of all the primary forests remaining in the province, Conservation North stitched together ten government data sets to fill in the picture. The resulting map, which the group titled “Seeing Red,” resembles a splotch of blood oozing across the landscape. It illustrates their main finding—75 percent of the province’s primary forests have been cut.

Yet the industry continues to expand. North of Prince George, where some of the biggest tracts of primary forest remain, Peak Renewables plans to build Canada’s largest pellet mill, in the heart of the boreal forest. These forests, stretching through Alaska and into Siberia, store about twice as much carbon in their soil, trees, and other vegetation as tropical rainforests. Responsible for storing about 17 percent of the earth’s carbon, Canada’s boreal forests have been referred to variously as a “carbon bomb” and a “giant carbon shield”—the former if destroyed, the latter if allowed to remain intact.

Meanwhile, at the United Nations Climate Change Conference in Glasgow last year, activists protested an event hosted by the World Bioenergy Association, with one protester stopping a train of wood pellets bound for the Drax Power Station, in North Yorkshire, which the company claims produces enough electricity to power the equivalent of 4 million homes. Drax has been making inroads into the pellet industry in Canada—earlier this year, it purchased Pinnacle Renewable Energy—and in the southern United States, North America’s other pellet hot spot. Subsidized by the UK government, Drax consumes pellets at a rate equivalent to about 194 hectares of forest per day, according to one estimate.

I asked BC’s Ministry of Forests to clarify the province’s rationale for promoting the pellet industry as sustainable despite the fact that pellet-burning power plants emit more carbon per kilowatt of energy produced than coal-fired plants. A spokesperson responded with a short series of bullet points and added, “Sustainably resourced BC forest products and reforestation efforts are at the core of our international efforts to address the global climate emergency.”

Booth, the American scientist, thinks this is deeply misguided. Nothing that’s combusted, she says, belongs in the same climate-friendly echelon as emissions-free wind and solar. “I understand people burn wood—I burn wood,” says Booth. “It’s just that treating it as renewable energy and incentivizing it is a huge mistake.” Every dollar subsidizing pellets as a green fuel is one that’s not going to wind, solar, or other truly clean energy sources.

APrince George forester tells me he appreciates Connolly’s concerns but thinks her idea about making pellets from only secondary forest is economically impossible. “I’ve submitted cutting permits for probably 5 million cubic metres of timber”—a cubic metre is roughly equivalent to the volume of a telephone pole—“and every single one has been primary forest,” says the forester, who didn’t want his name used because he didn’t have permission from his employer to speak to the press. BC’s secondary forests are generally less than sixty years old, he says, and have not yet matured enough to make logging on a large scale financially viable. “If you didn’t log primary forest,” he says, “there would be no wood-pellet industry, there would be no sawmill industry, there would be no forestry industry.”

Forestry, which contributed $5.6 billion to BC’s GDP in 2020, accounts for nearly a third of the province’s export value. Despite that, Mike Morris, the provincial legislator for the Prince George region, wants to prepare for a different economic future. “The industry has had a pretty prominent hold on all levels of government for the past seventy-five years,” he says. “We’re coming to a period where we are out of harvestable trees. And I think BC has an opportunity to change direction. Whether they want to or not, I think it’s going to be forced upon the province.”

Bob Simpson, the mayor of Quesnel, a small city south of Prince George and home to Pinnacle Renewable Energy, has a vision for what a lower-pellet future might look like. The town’s Forestry Initiatives Program—billed as a plan “to reinvent the forest sector from the ground up”—has emerged in response to multiple mill closures in the area and a recognition that pellet plants are not going to pick up the slack. “We’ve seen the writing on the wall and we’re doing a transition,” says Simpson.

Currently, about 90 percent of the pellets produced in Canada are shipped overseas. The pellet plants, which are run largely by machines, employ only about 300 people across the province, which means they have done little to replace the forestry jobs lost in BC. (The Wood Pellet Association of Canada says the industry employs 2,500 people when indirect jobs are included.)

Given that the pellet boom has benefited shareholders more than it has rural communities, and given its climate downsides, Simpson would like to see the province shift support to other forest products—especially so-called value-added products that result in a higher ratio of people employed per tree cut. This could include furniture manufacturing, but Simpson also sees promise in mass timber (a class of engineered wood products that can substitute for steel beams in large buildings) and technology to convert wood fibre into ingredients that substitute for petrochemicals in adhesives, plastics, and personal protective equipment. Besides providing economic diversification, such wood products are not combusted, which means they continue to store carbon.

When I spoke with Simpson, the mayor had recently come from a meeting with staff at Drax. “We pointed out that they’re just replacing the burning of coal with another emissions source,” he said. That kind of accounting mystifies him. “You disappear the pellet emissions on the premise that they’re being recaptured by the forests you’re regrowing—which is not guaranteed by any stretch of the imagination, particularly as climate change accelerates.” This fact hits close to home in Quesnel because the region has been ravaged by wildfires in recent years. In Simpson’s telling, the conversation didn’t go well. “The fellow from the UK and I agreed to disagree.”

BC’s inland rainforest once sustained vast numbers of southern mountain caribou, which survive the snowy winters by foraging for lichen. Partly as a result of forest loss from logging, the caribou are now an endangered species, with just a few thousand remaining in the province.

Before leaving BC, I drove with Connolly two hours north of Prince George to a place where one of the last herds congregates during the autumn rut. Antlers clashed. Lichen were munched. Some caribou napped on the ground; others pranced about, their breath steaming in the cold. As a migratory species, explains Connolly, caribou are especially sensitive to the confluence of habitat loss and climate change. Here, they feed on ground lichen. But, once the snow covers this resource, the caribou will move to lower elevations, where they can feed on species like horsehair lichen and witch’s hair lichen, which grow on branches up to three metres above the ground. They can reach those branches only because they’ve evolved oversize hooves that allow them to stand on top of the snow—otherwise the lichen would be too high.

If the caribou can’t reach those grazing grounds because development has fragmented the corridors through which they must travel, or if the snow isn’t deep enough to form an adequate stepstool, they may go hungry. The variables for survival are so finely tuned that there’s little room for error, says Connolly. “As the climate changes, they’ll need space to move around, to adapt.” But that space—that forest—may already have been processed into pellets.

This story was produced in collaboration with the Food and Environment Reporting Network, a nonprofit investigative news organization.