As soon as Harriet’s in, the second she hears the screen door bang shut behind her, she feels an arm come round her neck.

“Ranald?” She can hardly gasp the name. The arm tightens. Something with a point pushes into the small of her back. Breath—smelling of Juicy Fruit gum—blows hot across her cheek.

She turns her head to the right, and the pressure on her throat eases. It can’t be Ranald. He doesn’t chew gum. And not even Ranald would play a trick like this. “What do you want?” she says. Her voice surprises her—low and calm.

No answer. Just a sharp intake of breath. The arm at her neck is trembling, and she detects a tremor in the hard point digging in just below her back ribs. Is he just a kid? One of the town boys who stand in a sullen pack outside the 7-Eleven?

“Tell you what.” She tries to sound companionable, to take the tone she used to with Ranald when she had to coax him out of one of his sulks, give him some means of retreat with honour. “You can just let go of me. I won’t turn around. I won’t look at you. I’ll never know who you are. You can get out of here, really fast, and it will be all right. You won’t be in any trouble—”

She’s on the floor. On her hands and knees. A second shove, from a foot to her buttock, pushes her flat. She breathes in the dusty smell of the rag rug.

“Where is it?” He sounds as if he’s trying to make his voice deeper and rougher than it is. The foot gouges her buttock. “Where?”

“You mean—my money?” Another gouge. “My purse is in the bedroom. On the dresser. I don’t have much—”

He grabs her bathing-suit straps. Pulls her up onto her knees. She scrambles to get her feet under her. Then his arm is at her throat again. The pointy thing in her back.

“Go get it! Move!” His voice cracks on the last word.

They do a clumsy dance out of the living/dining room, around the corner, past the bathroom. She thinks of something and stops. He shoves her. “Wait.” He shoves her again. “No! Wait. Please. There is a mirror on the dresser. I promised I wouldn’t look at you. So put your hand over my eyes. Or turn us around and back us into the bedroom. That way, you’ll know I haven’t seen you.”

They stand still. She can feel him panting, can smell the Juicy Fruit on his breath. All at once, he swings her to the side, shoves her onto the bathroom floor. She slides on the tile, slams her head against the toilet. Sees stars. Hears him going into the bedroom. A clatter. A thump. Then he’s pounding past her, back through the cottage, out the door and gone.

Slowly, she sits up. Touches her head where it hit the toilet. No blood, but a goose egg rising. Her knees are red from where they skidded on the rug and the tile. Her elbow hurts. And she’s starting to stiffen up all over.

But she’s okay. And utterly amazed at herself. The way she remembered that trick of turning her head so she could breathe. When was the Safety for Seniors talk? Last winter. And she almost didn’t go. Figured it would just be common sense, nothing new. But she did go, and she did learn something. “If someone comes up behind you and puts their arm across your windpipe,” the young police officer told them, “turn your head into the crook of his elbow. That will give you some breathing space.” What would have happened if she hadn’t heard that bit of advice? She might be unconscious. Brain-damaged. Dead, even. She feels her head again. She should put some ice on that lump. She imagines it sticking straight up like a lump in a cartoon, pointy and bald, pain-stars orbiting round, and starts to giggle.

Is she in shock? Is that why she felt no fear, tried to negotiate with her attacker, and even thought to warn him about the mirror? Whenever she has imagined one of Ranald’s threatened scenarios coming true, she has seen herself terrified—witless and begging. Maybe the fear will come later. Right now, she feels proud of herself. Deserving of a treat. Ice cream? A gin and tonic before lunch?

Odd how she thought at first that it was Ranald, that he had driven up a day early without Patrick, hidden inside the cottage while she was down on the dock, and waited for her to come up the ramp. Just so he could grab her from behind and teach her a lesson. “I don’t like you up there by yourself.” When did he start standing too close, literally talking down to her, forcing her to peer up at him like a child? And when did he stop calling her Mom ? He doesn’t call her anything now. Just you. Thank God, he and Patrick aren’t coming till tomorrow. She’ll have time to put some ice on her head. Come up with a story. Anything would be better than the truth—that she left the back door unlocked while she was down on the dock, and one of the yokels, as he calls them, got in. So did she fall down the back-porch steps? Yes. That’s plausible. My injuries are consistent with a fall down the back-porch steps, she thinks, and giggles again.

Her purse. Damn. How will she explain having no purse, no keys, no money? She gets up, limps into the bedroom, and there, like an answer, is her purse lying open on the floor. Hanging onto the dresser with one hand, she bends carefully and picks it up. Credit and debit cards. House keys. Only the cash is gone. So, yes, her attacker must have been just a kid.

She should be on the phone right now, to alert the authorities. She almost giggles again. Alert the authorities sounds so pretentious. What could she tell them? That she was mugged by somebody with Juicy Fruit breath? Even if they managed to catch the kid, it wouldn’t make any difference. Boys will always gather outside the 7-Eleven with nothing to do except build up resentment against cottagers like her. Besides, Ranald might get wind of it if she makes a report. She can imagine him badgering an OPP officer, refusing to listen when they try to explain that if his mother did not see the kid’s face—

The car. Oh no.

She runs—stumbles—out of the bedroom around to the back door and looks out. There it is. Of course it’s still there. She’d have heard him driving away. She’d like to go out and touch it, but tells herself not to be silly. On her way back through the cottage, she does allow herself to check that her car keys are on the mantel where she always puts them when she comes in. Yes. There they are, on their ring with the big plastic daisy.

So there’s nothing to be done. She’ll just have her lunch. And she’ll have ice cream after, not gin and tonic before. Because she’s going to have to drive into town to replace her cash. And tomorrow she’ll tell Ranald and Patrick that she fell down the steps. Falling down the steps is less blameworthy than leaving the back door unlocked. Nothing for Ranald to lecture her about. Make her feel childish and stupid about. Yes. That’s what she’ll do.

Harriet is a painter. Right now, she’s in the middle of painting the lake as seen through the living room window. She has set her easel back far enough that it’s going to be as much about the window frame, curtain, and sill as the water.

Ever since she turned seventy, she has been thinking about doing a self-portrait. She never used to see the point of them, though she liked Rembrandt’s renditions of himself through the years. And while she stared into the mirror as much as any girl, her own young face never struck her as remarkable. Good enough cheekbones. Nose a little long, or maybe it was the short upper lip making it look that way. Wide-spaced hazel eyes—her best feature, she supposed, since they most resembled what she saw in magazines.

She’s not sure what Halvor saw in her. “Likely the top of my head,” she used to joke to company, when the talk turned to how they met. He was a tall young Dane whose family had immigrated when he was ten. In the first week of university, when he came up to her at a mixer, smiled down from his height, and asked her to dance, his accent thrilled her. Her own roots were Scots-English, and her family had been in Canada for three generations, so Halvor was exotic in her eyes. Her very own Viking. She liked his long hands and feet, his bony red face, his pale eyes like chips of blue ice. Above all, she liked his yellow hair that always shocked her when she saw it, as if it weren’t quite real. All the men in her family were dark, like her. Her mother was fair, but nothing like Halvor. “Going to stir up the gene pool with that one,” her father, a high-school science teacher, said when she told her parents she was engaged.

Her own hair is white now. If she finds an errant black strand, she pulls it out. She never coloured it, just let it go when it started to turn grey in her thirties, intrigued by the streaks coming in. Changes in her face and body intrigued her, too, over the years. She could never understand other women’s dismay over their sags and bulges and lines.

The only time she did not like how she looked—hated it, in fact—was when she was pregnant with Ranald. She wasn’t one of those women who glowed, who decided they were goddesses or some fool thing. The whole nine months, the nights upon nights she sat up in bed with heartburn, pounding her chest and drinking milk, which she disliked, she felt as if something were being done to her. And her labour was simply appalling. She couldn’t believe it. She alternately screamed at Halvor to go away and screamed for him to come back. Then, when they set Ranald bloody and squirming onto her stomach, the first thing she saw was his hair. Gucky black strands like an old man’s comb-over. Maybe if his hair had been yellow, if she had looked and seen a tiny version of Halvor . . .

“I didn’t know one end of the baby from the other,” she was finally able to joke to friends once Ranald was in school, and she had some time again. “Halvor had to show me how to feed him, how to change him, everything.” She was an only child, but Halvor was the oldest of five. And he loved being a father—would rush home from work to be in time to give Ranald his bath. “These big hands,” she would say, “and so gentle.”

Until Ranald was born, Harriet had no idea how much she was counting on her and Halvor’s life together continuing the way it always had. When Halvor went off in the morning to the civil engineering firm that had recruited him right out of university, she would tidy and scrub. She loved their little apartment in the middle of downtown, would never let a hair remain in a sink or a snarl of dust gather behind a door. Once the housework was done, she would read until it was time to fix the Danish open-faced sandwiches Halvor had taught her to make. They would go to bed after lunch, and she would almost have to push him out the door or else he’d be late back to work. Then in the afternoon, she would paint in the sunroom, where there was just space for her easel and a cabinet full of brushes and tubes of oils. Most often, she painted the view from their apartment—roofs and treetops and backyards, all through a criss-cross of electrical wires. She has always loved the backs of things. Her favourite portrait of Halvor is one she did of him from the back. His eyebrow showed, and one sharp cheekbone, the line of his jaw, his neck, and part of a naked shoulder. But the focus was that hair, glorious and yellow, still young and bright, right up until the day he died.

She never painted Ranald, though she did do a few sketches of him sleeping when he was little. He would not sit for her, refused even to try, and she was secretly relieved. The idea of being alone with her son for hours in the taut silence that stretches between sitter and portrait artist filled her with a kind of dread.

For years after Ranald was born and they had moved from the apartment to a bungalow just north of the city, she could not paint at all. It wasn’t just lack of time. Everything around her was too spacious and blank—the lawns, the roads, the shopping malls. She felt as if she were getting lost in all that space—thinning out, stretching, becoming as transparent as the sky. Gradually, as Ranald grew and left her alone for longer periods of time, she managed to gather herself back to herself. She found that she could paint her suburban world from inside the house, framed by a window. It was good practice for painting the lake up at the cottage, which at first overwhelmed her with its immensity.

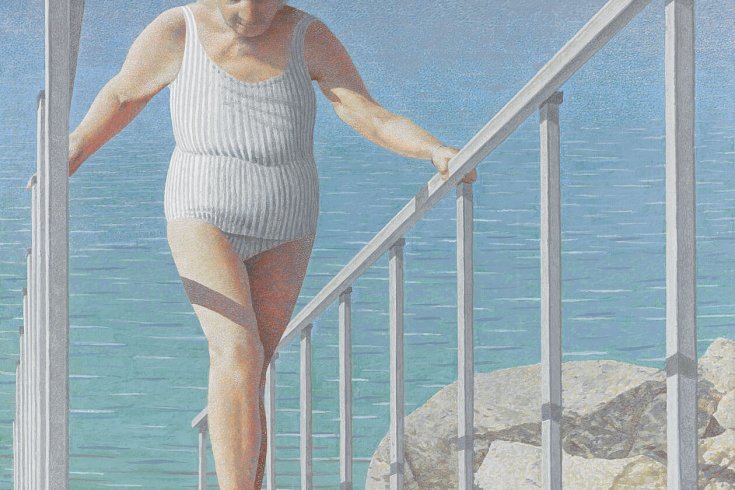

Twice this summer, she has started a self-portrait. She has rigged up a mirror beside her easel, blocked in some colour, then scraped the canvas. She worries about committing something hokey like Norman Rockwell’s portrait of himself painting himself. But she can’t give up on the idea. She has looked through photographs Halvor took of her, thinking she might work from one of them. He’s been dead for eleven years, so the oldest she appears in any of them is fifty-nine. There’s one of her coming up the ramp, head down, watching her feet. She supposes she could age the figure, thicken the body and whiten the hair.

Lately, she’s begun to wonder if what she really wants is not to paint herself but to be painted. To be seen. We will witness to each other’s lives. She and Halvor had that written into their marriage vows.

Lunch. That’s why she was heading up the ramp from the dock in the first place. And some food will raise her blood-sugar level. And that might—what? Wake her up? Make her shake? Cry? Maybe she is in shock. Were it not for her stiffness and bruises, she could believe she dreamed what just happened.

In the kitchen, she cuts a generous slice of the cold meat loaf she brought with her from the condo. She checks that the mustard is out on the Lazy Susan on the dining table, chops up a tomato, puts the chunks in a bowl, then adds some sugar snap peas for green. There’s a half baguette in the breadbox. She puts it on the board with the breadknife and butter bell, chooses an apple from the fruit bowl on the counter, thinks about the three arrowroot cookies sitting in a little dish in the fridge, then remembers ice cream. Her reward for being brave. If that’s what this calmness is.

She isn’t even angry with Halvor. For years after his death, if something bad happened, she would get furious with him for not being there to help her deal with it. Well, maybe that’s the last bit of her grief gone. She’s heard of people forgetting what their dead spouses looked like, having to use photographs to bring them to mind. That’s not happening to her, surely. She could still paint Halvor from memory.

She carries her cobbled-together lunch to the table and sits down. Saws off a slice of baguette and butters it. Patrick gave her the butter bell after she complained that because she was on her own, it took her forever to work her way through a pound of butter, so her choices were rancid or hard. There you go, Harriet. All your butter problems solved. She likes Patrick. He’s short and plumpish, a little like her. The two of them can smile directly into each other’s eyes while Ranald stands apart and watches. Patrick teaches grade three—“They’re just getting interesting at that age, Harriet, turning into real little individuals”—and he acts as a buffer between her and Ranald. “Now, can I trust you two while I go and do the dishes?” Treating the tension between them like a naughty joke, something to shake a finger at.

She crunches a sugar snap, thinking how much Halvor would have liked Patrick. Halvor was the one who first got the news that Ranald was gay. She herself had suspected it for years. The guilt she felt was not about that, but about his having gone to his father. Wasn’t the mother supposed to be the approachable one when it came to things like that?

But right from the first, Ranald had been like a little pebble. She skidded off him. Couldn’t get in. Trying to interpret his shrieking, wordless demands exhausted her and scattered her wits. She could hardly get a sentence out to Halvor, and when she tried to return to a painting she had started in her seventh month, it was like staring at some stranger’s graffiti.

Even when he went from being a baby to being a little boy, Ranald stayed closed off from her. She would find him hunched over a skinned knee, crying soundlessly, and would have to beg him to let her see it, let her clean it and put a bandage on it. The two of them spent their days living for the moment Halvor walked through the door. Harriet should have been jealous of the way the boy ran to his father, but all she could feel was guilty relief.

So of course he came out to Halvor. It happened when he was in third year, doing a combined major in art history and math. They had sold the bungalow by then and moved into the two bedroom–plus-den condominium Harriet still lives in, and that Ranald is pressuring her to sell. She remembers trying to paint that afternoon in the south-facing den she had turned into a studio, but not being able to concentrate, too aware that Halvor had been with Ranald in his room for hours with the door shut. Was Ranald having second thoughts about being an architect? Then when the door opened and she saw them standing together—the boy with his father’s height, her hair, and a perfect mix of their features—she knew exactly what they had been talking about, what had happened. Ranald’s eyes were wet. He came to her and hugged her, awkwardly. She has tried to remember the embrace alone, to forget the small gesture Halvor made just before it, as if cuing his son to do something he had managed to convince him to do.

Harriet goes to saw off another slice of baguette, then thinks no. The last time he saw her, Ranald asked pointedly whether she had been gaining weight. Patrick said, “Ranald!” but did not contradict him. She has thought about asking Patrick to call her Mom . Would Ranald take it badly? Probably.

She shakes her head, putting the breadknife down. She did her job, all the mother things, as well as she could. She walked Ranald to school, holding his wrist, since he would not open his hand to hers. She hosted birthday parties with balloons and paper streamers and themed cakes—cowboys, pirates, space rangers. She made Halloween costumes and stuck drawings onto the fridge door and took pictures at every milestone. But all three of them knew it was a waiting game for her. Just a matter of getting through, doing her time, till she could get back to her brushes and paint. “I was a fake mother, Halvor,” she says, chewing a chunk of tomato. It’s the first time she’s talked to him today. “Totally bogus.” Harriet, you did your best. When she imagines him answering her, his accent is as thick as it was when they first met. And the boy survived. He’s as happy as he’s going to be. So.

She’s pretty sure that’s what he would say, the attitude he would take. He didn’t seem to mind having to be a parent and a half. And the two men loved each other — no doubt about that. She remembers them bent over the blueprints of this cottage—Ranald the young architect answering the questions of Halvor the engineer. The happiest she ever saw Ranald was when he and his father were supervising the construction.

“I still get a laugh out of the ramp,” Halvor chuckled to her in bed that Friday night after they had driven up to the cottage to spend the weekend by themselves. It was the last night of his life. “He’s got his old parents in wheelchairs already, in his mind.”

He drowned the next morning. He had gone for the swim he always took while she fixed lunch for the two of them. She got interested in a talk show on the radio and didn’t notice for a while that he had been in the water longer than usual. The autopsy showed signs of a heart attack.

Harriet forks a bit of meat loaf. Dips it in mustard. Feels a twinge in her elbow and wonders what her attacker is spending her money on right now. She can just hear Ranald: He’s probably divvying up the cash among his friends, having a big old laugh about how easy it was. And he’ll be back. But he’ll bring his friends with him. They’ll take baseball bats to the windows, get in and trash the place. And God help you if you’re here when they come.

“Keep your hopes up, Ranald.”

The tone of her voice shocks her—not just the fact that she has spoken aloud. She’s been talking to Halvor for years, but never to Ranald. Would she ever say something like that to his face, something flat and hard like a slap, when he gets going about how utterly helpless she is? Maybe. It would upset Patrick. But for once she can imagine herself doing it.

She’s always been so careful around her son. There’s never been a big blow-up between them — she’s seen to that. For the first year after Halvor drowned, Ranald could hardly look at her. Hoping to siphon off some of his rage, she made a point of telling him that she blamed herself for his father’s death, that she couldn’t stop wondering whether Halvor had called for her. He never swam far out. If the radio hadn’t been on, might she have heard him?

As the years passed, she and Ranald achieved a kind of sullen peace. The question they both knew he was silently asking in those early days—why couldn’t it have been you in the water instead of him—was never given voice. She wonders sometimes whether he ever voiced it to Patrick. She can imagine Patrick listening calmly, then forgiving and comforting Ranald as he would one of his grade threes.

Harriet finishes her apple and decides she doesn’t really want ice cream after all. Instead, maybe when she gets back from town, she’ll treat herself to a gin and tonic. She carries her lunch dishes into the kitchen, puts them on the counter, and squirts dish detergent into the sink. Then decides the cleaning up can wait. And she doesn’t really have to go to town right now either, does she? She could she leave it till tomorrow morning.

So what does she want to do? She stands still in the middle of the kitchen, feeling vague, distracted. Maybe a nap?

Curled up on the bed, still in her bathing suit, she stares at the wall where the first painting she ever did of the lake is hung. For a year after Halvor drowned, she didn’t paint at all. Then when she did finally pick up her brushes, she took the lake as her subject. This first one shows the end of the dock in the foreground—the spot where Halvor would have entered the water. It’s not terribly good. The waves are too opaque. She’s gotten better over the years at capturing their translucence and movement. But she never paints the lake alone. Always, there is something solid—a bit of the dock, the frame of the window—as a counterpoint to the water. Context. Something to ground it.

She turns onto her back. Sighs. This nap isn’t going to happen. She gets up and pads barefoot into the living room. There, propped on her easel, is her half-finished painting of the lake as seen through the window. It’s going to be good. One of her best. But it needs something. It’s too neat. Predictable. She picks up a brush. Puts it down. Studies the tubes of paint she selected, the coloured stains on her scraped palette. Finds herself, oddly, thinking about her car keys. The plastic daisy on the key chain. Should she add them in, maybe have them sitting on the windowsill? Would that give the painting some oddness, a bit of an edge?

This is getting silly. She needs to get her act together. Do those dishes. Then drive into town and get some money.

She changes out of her bathing suit into shorts, a T-shirt, and sandals. Washes and dries the lunch dishes. Goes and gets her car keys. Scoops them up. Turns toward the door. Stops. Turns back. Stands looking at the arrangement of objects on the mantel.

Something is wrong. Something is missing. She didn’t notice before, at least not consciously, because she was so relieved that the keys were still there. But now she takes inventory. There’s that piece of driftwood shaped like a horse’s head that she and Halvor found. The Mason jars of rocks and shells they collected over the years. Framed photographs. She and Halvor on the deck raising champagne glasses to the newly finished cottage. Ranald and Patrick in their white tuxedos, paddling their canoe up to the dock, where the wedding guests waited. And, in the middle, a long shiny space free of dust.

The wooden bookmark. That’s what’s gone.

Ranald whittled the bookmark for her the summer he went to art camp. He was twelve. When they picked him up to take him home at the end of the month, he held it out to her, eyes averted, mouth grim. He had shaved an oblong of pine thin at one end. At the thick end, he had shaped a raven—caught the hulking posture of the bird, and, with just a few nicks, suggested ruffled feathers.

The narrow end of the bookmark is what she had felt poking her in the back.

“How dare you!” She can hardly get the words out, her jaw is so tight with rage. Rising. Filling her up to her hair roots. “How dare you!” She grips her car keys. Stomps to the back door. Yanks it open. Slams it shut behind her and locks it. She can feel her blood pulsing as she starts the car. Righteous wrath. That’s what this is. And it feels good. Feels good even just to say it. “Righteous wrath!”

She wasn’t sure she liked the bookmark at first. But she tried, loyally, to use it. The thin end wasn’t thin enough. It bent the covers of her books and kept falling out. So she tried opening letters with it, but the edge was too dull. Finally, she said brightly to the young Ranald, “I want people to see this. I’m going to display it on the mantel in the living room.” Ranald said nothing, his face as closed to her as it ever was. And in bed that night, Halvor made one of his rare criticisms. “You should have told him what the problem was. That way, he could have fixed it. Or he could have made you a new one. A better one.”

It was one of the few times she got really angry with Halvor—a deep, sulky, childish anger that hung between them for more than a week. It would have been so easy to make things right—agree with her husband and tell her son the truth. And maybe, she realizes now in the car on the way to town, if Halvor had said “why don’t you” instead of “you should have,” she might have approached Ranald. Had that conversation. But she never did. The bookmark, still useless, stayed on the living room mantel. Years later, when the cottage was built, she brought it up and displayed it there.

She drives straight to the 7-Eleven. And there they are, slumped against the wall in their hoodies like crows on a wire. She pulls into the parking lot. Brakes hard. Gets out and slams the car door behind her. Marches straight toward the line of boys, thinking righteous wrath. Crackling with it.

Their lips curl at the sight of her, then sag as she keeps coming. When she doesn’t stop, they glance at each other and melt away, back behind the wall, down the alley. All but the one in the middle. The one who recognizes her. He stands as if impaled by her approach, his eyes frozen on hers.

She plants herself in front of him. Glares up at him. The boy’s lip and chin are a rubble of pimples and stray black hairs. What is he — fifteen? She leans in and takes a whiff. Juicy Fruit.

She puts her hand out. “Give it back.”

He blinks. Slumps. Reaches into the pocket of his hoodie jacket and pulls out some crumpled bills.

“No. Not the money. You can keep that. But you’re going to earn it.” She keeps her hand out.

More slowly, he reaches under the bottom of his jacket. His jeans pocket. A secret place, hidden from his gang. He pulls out the bookmark. Holds it toward her.

“Handle first!”

He turns it, and she takes it from him. Holds it up in front of his face. “My son made this. For me. When he was younger than you. Look at me!” The eyes jump back to hers. “He made it! Do you understand what I’m saying to you? You can make things!” Oh, she could grab him by the shoulders, big as he is, and shake the living daylights out of him. She could haul back and slap him silly.

“Turn around.” He does. “Pull your hood down.” His hands shake. His hair at the back is a greasy mullet. “Put it back up.” He does. And yes. There it is. Exactly what she needs.

“All right. You can turn around again. Look at me. I’m a painter. I need you to pose for me with your hood up. I’ll paint you from the back. It’s hard work. You have to stand still for long stretches until I say you can take a break. That’s how you’ll earn the money you took from me. And if it takes longer than this afternoon, I’ll pay you more. Come to my place in an hour. You know where it is.”

Back in the cottage, she retrieves Halvor’s photograph of her coming up the ramp and tapes it to the top of her easel. The angle is going to be tricky. Everything as seen through the hidden eyes of the hooded figure that will occupy the foreground. The window will be centred. Through it, a bit of the lake will show. And off to one side, in the bottom corner of the window frame, she will paint herself. The way he saw her.

That’s important. She has to capture the aloneness. The unawareness of being watched. Waited for. It’s not just a question of adding years. She has to look at this woman and see someone she no longer is. Get past the familiar. Paint what is already strange and gone.

It’s easier to imagine the boy. Sent there by his gang to get money. Distracted by the bookmark. Looking at it and seeing a dagger. A raven totem. Picking it up. Turning and holding it to the light. Catching sight of her coming up the ramp.

With a few strokes, she outlines the woman ascending. And from behind, the hooded figure waiting. Watching.

She paints. It would be so easy to lose track of time. But she keeps an ear cocked for the sound of the back door opening.

This appeared in the May 2016 issue.