On September 17 last year, New Democratic Party leader Jagmeet Singh was heading into Parliament when a pair of protesters started heckling him. By then, far-right groups had been holding daily demonstrations in Ottawa for nearly three years, ever since the end of the so-called Freedom Convoy, so a run-in like this was hardly unusual. What made it different was what happened next.

As captured on video, Singh was walking away, ignoring a rather wonkish question about a possible no-confidence vote, when one of the protesters called him a “corrupted bastard.” At that point, Singh—well dressed, as usual, in a tailored suit and pink turban—stopped, spun on his (presumably) designer heel, and headed straight at the two men.

“You wanna say something?” Singh asked. “You wanna say something to me?” The heckler—clearly the guilty party, as even his compatriot acknowledged with a traitorous nod in his direction—pleaded ignorance and pretended to be absorbed by something on his phone. Singh wasn’t having it. “’Cause you’re a coward, you’re not gonna say it to my face,” he said, his nose inches from the other man’s. “That’s what’s up.”

The video went viral, with YouTube comments revealing a common theme: “Not a Jagmeet fan at all, but good on him for calling buddy out who was a coward!” “Not a fan of this guy at all but respect for him for standing up for himself instead of walking away like many would, and giving these keyboard trolls a reality check.” “Go ahead and say it to Mr. Singh’s face if you have the balls.” And so on. The message was clear: when Jagmeet Singh confronts right-wing weirdos, people take notice.

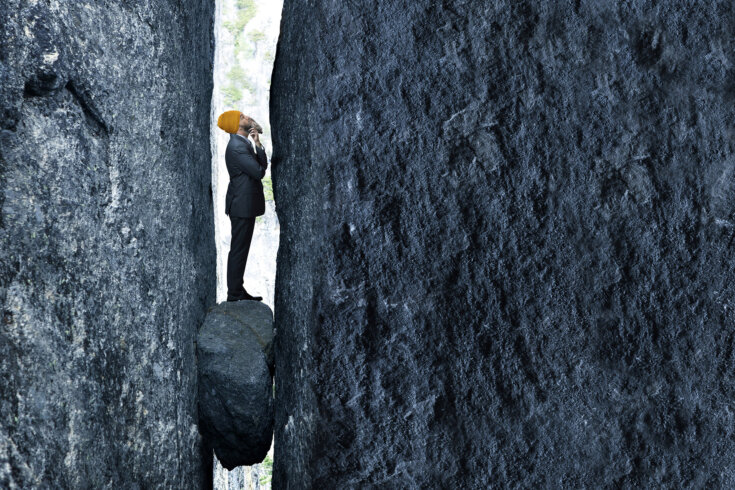

The problem is that, in his nearly eight years leading the federal NDP, this side of Singh has shown up far too rarely. That shouldn’t be the case. Singh’s personal story is unlike any other in Canadian politics: a practising Sikh, a survivor of childhood sexual abuse, a criminal defence attorney who worked his way through law school. An intelligent and charismatic figure, he can claim tangible policy wins that Justin Trudeau would never have enacted on his own. Without the NDP’s supply-and-confidence agreement with the Liberals, there would be no Canadian Dental Care Plan, no Pharmacare Act, no Early Learning and Child Care Plan—goals that the progressives had been working toward for decades. On paper, Singh is a once-in-a-generation political talent and has achieved more than some prime ministers.

But that’s just on paper. In reality, Singh is a failure—although, to be fair, his failures are shared by every single one of his predecessors. Singh, for all his gifts, hasn’t figured out how to make the NDP a serious prospect for power. He hasn’t come up with a vision for the party that is sufficiently bold or clear enough to differentiate it from the Liberals. And he appears unable to decide whether to take the party to the left or make a play for the mushy middle. The very supply-and-confidence agreement that has resulted in so much progress has also bound his fate to Trudeau’s. He’s proven that the NDP, as always in its history, is most effective at the national level when it has a vulnerable Liberal government to dangle over the ledge.

Singh also hasn’t come up with a social democratic version of the Conservatives’ anti-Trudeau populism. In Europe, leftist parties have recently found success in both articulating an alternative to dead-end liberalism and stopping the far right: see Die Linke’s resurgence in February’s German elections or the Nouveau Front Populaire’s victory in last year’s French parliamentary vote. But the NDP hasn’t figured out how to translate that particular playbook here. Although Singh is now, on the campaign trail, trying to distance his party from the Liberals, it isn’t resonating. In poll after poll, the NDP just keeps sliding.

And that’s the most crucial test of all, for any party leader, of any affiliation: can you win, or at least gain ground? Singh hasn’t led the NDP to anything remotely resembling victory—quite the opposite. During his first campaign as leader, in 2019, the NDP’s parliamentary seat count plummeted from forty-four to twenty-four, behind even the Bloc Québécois, and it remains unchanged today. If the polls are accurate, the party stands to fare even worse when the writ drops this spring, potentially losing as many as half its seats.

The NDP’s predicament might not be Singh’s fault; any other leader of Canada’s “party of conscience” could have wound up in similar straits. But this is the price a man like Singh must pay for believing in political possibility, rather than just scrambling for position from the Liberal back benches like so many power-hungry, ideologically chimerical nobodies before him. Canadians get involved with the NDP—they vote, they volunteer, they run for office—because they have faith that the party means something. Under Singh, it’s not clear what that meaning is.

Singh’s challenge has become especially acute given the scrambled stakes of the coming election. What was once a referendum on Trudeau’s performance is no longer that. The Liberals’ fortunes have improved since the prime minister announced his resignation, with poll trackers giving the party a ten-point boost, most of which has come at the NDP’s expense. It’s a familiar pattern in Canadian politics: the NDP does well when the Liberals are either assured victory or absolutely cooked. Right now, the Liberals are neither—which might explain why one poll has the NDP down to ten points, which would be the party’s worst showing in decades.

Nor has the current trade war with the United States been good for the NDP. Voters appear to be sailing for safer harbours, and if anyone has benefited from Donald Trump’s tariffs on Canadian imports, it’s once again the Liberals. Although the Conservatives still hold the lead, it’s narrowed considerably, and one poll suggests that most voters think newly minted Liberal leader (and prime minister) Mark Carney, a former Bank of Canada and Bank of England governor, would handle trade negotiations with the US better than Pierre Poilievre of the Tories.

So where’s the NDP in all this? Singh is struggling to break through. He’s proposed a 100 percent tariff on Tesla imports—a good idea and a trollish jab at Trump ally Elon Musk. But Singh swiped it from former Liberal leadership contender Chrystia Freeland, who’d suggested it weeks earlier. In his talking points, Singh has tried to connect the potential damage of a trade war to Canada’s ongoing affordability crisis. This sort of thing is the NDP’s bread and butter—using a top-of-mind news item to draw attention to a broader economic concern. But what this connection actually means, and what the party will do about it, remains vague.

In any case, right now, Canadians seem more interested in a steady hand at the wheel of trade negotiations than a discussion about wealth redistribution during a hypothetical tariff-inspired recession. In provinces where the NDP has formed a government, the party might be perceived as a reliable steward of the economy, but these are all places where they occupy the ideological space that would otherwise belong to the Liberals. In Manitoba and Alberta, the Liberal brand is so toxic as to be practically non-existent, while in British Columbia, the Liberals function as the centre-right party to the NDP’s centre-left.

On the federal level, of course, the NDP has never come close to taking power. And if Singh can’t convince Canadians his party represents more than a protest vote, it never will.

Once upon a time, the NDP would have been well positioned to capitalize on a moment like this: economic precarity, political upheaval, a convenient enemy south of the border. Today, Canadians of all stripes are suddenly economic nationalists, urging boycotts of American products and protectionist policies for domestic industry. In its earlier years, the NDP was very much this kind of party, with leader David Lewis forcing a weakened Pierre Elliot Trudeau—sound familiar?—to create Crown corporations like Petro-Canada and interventionist tools like the Foreign Investment Review Agency, which screened new ventures to ensure they helped our economy. (Now, of course, Petro-Canada is privately owned, and the since renamed Investment Canada is a rubber stamp.)

At the time, the NDP was almost torn apart over just how far to take these matters, and the party’s internecine battles in the late 1960s and early ’70s have become the stuff of Canadian political legend. Back then, a radical movement calling itself the Waffle—a tongue-in-cheek name for an internal faction fed up with the NDP’s hemming and hawing—tried to seize control of the party on a platform of far-left nationalism and nearly succeeded. The Waffle’s founding manifesto was prescient. “The major threat to Canadian survival today,” its authors wrote, “is American control of the Canadian economy.”

But the tide of anti-Americanism currently sweeping Canada recalls nothing so much as the free trade wars that roiled the country in the ’80s. In his first term as prime minister, Brian Mulroney began negotiating a free trade deal with the US, which both the Liberals and the NDP opposed. “With one signature of a pen,” Liberal leader John Turner told Mulroney during a televised debate, “you’ve thrown us into the north–south influence of the United States and will reduce us, I am sure, to a colony of the United States.” (The fifty-first state, indeed.) In the 1988 election, the Liberals made their opposition to free trade a signature issue, while the NDP—in a misguided attempt to maximize the party’s appeal, and over the furious objections of its trade union members—mostly stayed quiet. Of course, Mulroney’s Progressive Conservatives won. We’re still living with the consequences.

The Liberals, like every other centre-left party in the Western world, eventually dropped their opposition to free trade, and under Jean Chrétien, Mulroney’s Canada–United States Free Trade Agreement became the North American Free Trade Agreement (which, in turn, Justin Trudeau was forced to renegotiate as the Canada–United States–Mexico Agreement, a mostly meaningless update that nonetheless allowed Trump to claim victory). The NDP’s position on free trade, meanwhile, has softened to the point of meaninglessness: free trade is good when it’s good for Canadian workers, bad when it’s bad for Canadian workers, and such agreements must always include social and environmental protections. It’s not altogether different from that of the Liberals, who at least have the decency to be more specific.

If Trump follows through on the full extent of his threatened tariffs, they’ll devastate the Canadian economy, and the infrastructure of global trade is now too entwined for any kind of unilateral rollback to be the answer. But governments around the world are currently reassessing the wisdom of the neoliberal turn of the ’80s and ’90s. The free trade era may have resulted in some economic opportunities and cheap goods, but it’s had devastating consequences, the sort its opponents—the early NDP among them—warned of from the very beginning: the decline of manufacturing in places like Canada and the US, the creation of vast swaths of exploitation in the Global South, and, as it happens, the very economic and social erosion that has given rise to reactionary populists like Trump.

Trump has proven, in this and many other arenas, that the so-called rules-based international order is only as stable as the mental well-being of whoever happens to be the president of the US. If the NDP had remained true to its roots, it might have had a meaningful battle plan for fighting Trump’s trade war. As usual, though, the party is missing in action.

After this election, regardless of the outcome, Singh will probably face a leadership challenge. Even if he hangs on, he’ll still be brought down by a familiar nuisance. Pretty much since the NDP’s founding, in 1961, as an alliance between the Canadian Labour Congress and the Co-operative Commonwealth Federation, the party’s chief internal struggle has been the age-old question of whether it should tack to the centre or the left—whether it should try to beat the Liberals at their own game or remain faithful to its organized-labour and prairie-populist origins.

Over the years, the party has vacillated, with mixed results no matter the approach. From the ’60s through the ’80s, when the party was at its most progressive, its highest seat count was forty-three. Jack Layton, the architect of the NDP’s push to the middle, oversaw its stunning rise to 103 seats and official opposition status in 2011, but that owed just as much to the collapse of the rudderless Liberals and the useless Bloc Québécois as any brilliant strategy on his part. And in the next election, under Thomas Mulcair—Layton’s all-but-anointed successor, an avowed moderate, and a former Liberal to boot—the party’s seat count plunged back down to forty-four. Under Singh, of course, it’s only dwindled further.

One of Singh’s chief shortcomings might be that he represents neither faction of the party. He’s avoided the obvious mistakes of Mulcair, who allowed the Liberals to outflank the NDP from the left. But he’s also failed to inspire the kind of grassroots energy that can transform a candidate—or a party—into a movement. Nor has he managed, like some skilled leaders, to turn this ambiguity into a unifying force. Instead, he’s muddled along, earning political victories without political power.

That might be why the version of Singh who appeared in that viral video, his finger in the face of some right-wing nut job, felt so refreshing and so unfamiliar. No one should expect a politician to solve all our problems. But it’s nice to see one who isn’t afraid of a fight.

On Friday, April 25, join us for The Walrus Talks at Home: Tariffs. Four expert speakers will discuss what the U.S. tariffs on Canada mean, both now and in the future. Join us online. Register here.