In July, we partnered with the podcast What Happened Next, produced by author Nathan Whitlock. It’s a terrific show about, in Whitlock’s words, talking to “other writers about the times between books, when a book is no longer new and it’s time to write another one.” A couple of weeks ago, Whitlock spoke to writer and journalist Deborah Dundas, formerly the books editor for the Toronto Star and now one of its opinion editors. The occasion for the interview was Dundas’s first book, On Class, published by Biblioasis in 2023. But the two began by talking about Andrea Robin Skinner’s memoir that exposed her stepfather’s sexual abuse and Alice Munro’s knowledge of it—a story Dundas edited for the Star.

Here is an excerpt of that specific section of the exchange, which includes revelations that, to our knowledge, haven’t been aired yet. Of course, we encourage you to listen to the rest of the interview, available here, and to look for new episodes, which drop every Monday morning.

The excerpt has been edited lightly for clarity.

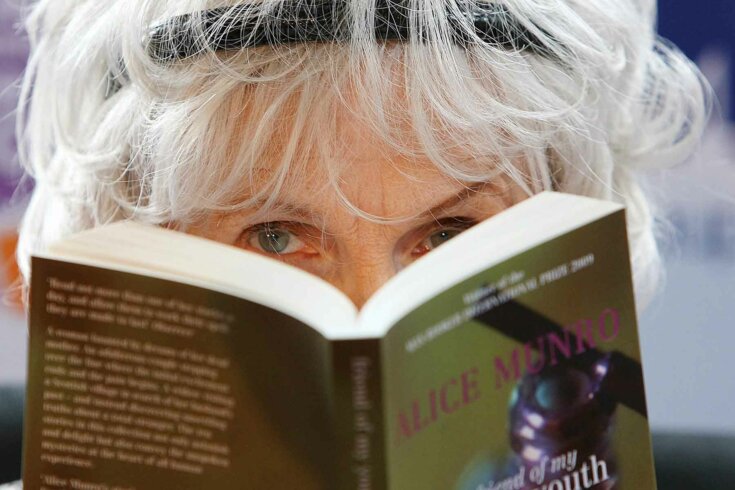

Nathan Whitlock: It has not been a quiet summer for you. I’m referring to the story about Alice Munro’s daughter that has become this massive international talking point, beyond just book chatter. I have to ask: Can you give us a little bit of an inside view into how that all came about?

Deborah Dundas: Andrea Skinner—that’s Alice Munro’s daughter—approached us. She had approached, from what I understand, media outlets before, and nobody wanted to touch the story.

Whitlock: Can you name the ones that said no?

Dundas: I can’t, actually. I don’t know who they are specifically. Well, I do know a couple.

Whitlock: This isn’t Canadaland, so I’m not going to press you on that.

Dundas: The nut graph of the story is that Andrea Skinner was the youngest daughter of Jim Munro and Alice Munro. They split up. Alice came to live in Clinton, Ontario, and she ended up living with and marrying Gerald Fremlin. He sexually assaulted Andrea when she was nine years old. The family kept it a secret, sort of, within the family. Some of the family didn’t even know, and the decision was made not to tell Alice. So we’re not sure whether she really knew either.

When Andrea was twenty-five, she wrote to Alice and said this is what happened. And Gerald wrote some letters very explicitly detailing what had happened. And there was a bit of drama—well, a lot of drama—for a couple of months. And then Alice went back to him. Andrea was twenty-five at that point. In 2005, Andrea gave those letters, that were conveniently written, to the OPP—the Ontario Provincial Police. She was living in Ontario at the time, and he was charged, and he pleaded guilty to one count of indecent assault and was given a two-year probationary sentence. So that was the upshot of it. Once that conviction was in hand, she let people know about it, but nobody picked up on it. And nobody picked up on it from the courts. I mean, it happened in Goddard [Goderich]. It’s a small town.

Andrea tried to get the story out over the past twenty years, and nobody paid attention to it. And those who, maybe, were in positions to actually get the story out there, and have it told, weren’t interested in having it told. So she emailed a colleague of mine, Heather Mallick, with her story. Heather, instead of ignoring it, passed it on to one of our senior editors, and they asked me if I’d do the story. And I said: No. I don’t want to do that. I don’t want to take down an idol.

Whitlock: That was your initial feeling, like, I can’t touch this?

Dundas: Because I didn’t want to bring down an idol. I didn’t want to jeopardize any of the relationships I’d spent years building in the publishing industry, relationships I had with people who trusted me. So I thought about it, and later in the day, my editor called me back and said, “Are you sure about this?” I had been thinking: I know the industry, I know the people involved. If anyone can approach it sensitively, it’s probably me. It’s better to have someone like me do it than a reporter who’s sort of “hard news” going for it, because I could fit some nuance in.

Whitlock: You could imagine someone like a Kevin Donovan, or a Robyn Doolittle, or someone who is more straight-up investigative news. You can imagine them writing a very different version of that story.

Dundas: Well, that was the thing. I mean, it was funny. I was joking that I felt like Robyn Doolittle, because it was that kind of big story. But, yeah, that’s what I thought. Now, it was decided Andrea would write a first-person story about it. But, of course, you can’t just say, “Okay, well, write a first person, and we’ll publish it”—not about something like that. So we need the investigative piece to back it up. There was proof. The letters and the conviction were proof, but we still needed to build all of that and explain why and what had happened. That was what fell to me, and I knew who we could contact in the publishing world. It was mostly unknown until the conviction, but then, after the conviction, not entirely, and some people knew before. I don’t think it really reflects well, necessarily, on some in the publishing industry that it was kept secret. It was easy enough, mostly, to get them to talk—not entirely, though.

Whitlock: I don’t consider myself necessarily an insider in terms of books and publishing, but I feel like I know a lot of insiders, and I talk to them, and there have been some big, high-profile scandals in Canadian writing in the past decade. And to be perfectly honest, when those came out, I was like: Yeah, I knew that was coming. This one I read in the Star the day it came out. And like with a lot of people, my stomach sank, because I’m an enormous Alice Munro fan. So weirdly, one of my first reactions was: How did this not get whispered about? But clearly, it was being whispered about, in some circles.

Dundas: I sort of have the same approach as you do. I consider myself a person who knows a lot of publishing insiders but don’t necessarily consider myself a publishing insider. I mean there has to be a certain amount of distance, even though publishing is built on relationships, right? It’s a very weird line we walk sometimes, you and I, Nathan, when we’re sort of navigating all of this. But I had never heard any whispers.

It’s funny. It sort of echoes what was going on in the family. Certain people knew little bits of it, but I don’t think anyone knew all of it within the family until Andrea talked about it, and until the conviction. From what I understand, from talking to a number of Alice’s friends, they didn’t know about it. Or they knew about it after the conviction, or after Gerald died. And I think: Okay, you know, that’s kind of there enough. I think there was a group of people who knew about it, and they were sort of tangential to the publishing industry. So those would be the ones who knew. I don’t think it was widespread in the publishing industry. Alice had her book friends—her colleagues-slash-friends. I think they thought they knew her—but didn’t in as close a way as they thought. I think we probably all have friends like that, right?