At the beginning of Montreal’s municipal election race in September, nobody even knew Denis Coderre’s main challenger. Valérie Plante was an academic, an anti-poverty activist, an outreach worker for victims of domestic assault. The thought of her ascending to the mayoralty of Canada’s second-largest city, a metropolis that has become synonymous with an old boys’ club of kickbacks and collusion, was, for the city’s progressives, a pipe dream and, for its political class, a running joke.

But now, Plante has come out as the surprise winner of a sleeper election campaign. As results rolled in on Sunday night, she and her party notched an impressive victory, gaining a majority on city council, one of the few in Canada that allows political parties. She becomes Montreal’s first female mayor and stands to be one of the most important local politicians in the country—one who is promoting an aggressive urbanist agenda and who has plans for massive new infrastructure developments that few other local politicians are brave, or deluded, enough to pitch.

Her decisive victory over long-time political juggernaut Coderre may also signal a sign of things to come across the country.

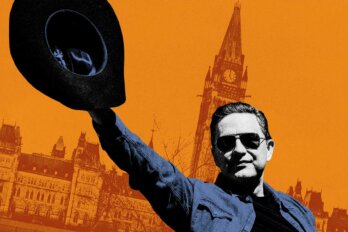

Last election, Coderre—the former MP who has been a stalwart Liberal lieutenant in the province—was running on a campaign to clean up the endemic corruption that had plagued the city for decades. His competitors: the affable Mélanie Joly, political upstart; Marcel Côté, experienced set of hands from the city’s financial district; and Richard Bergeron, kooky leader of the left-wing, ecologically minded Projet Montréal.

Coderre handily won the four-way race. Joly came a close second but failed to win her district and later made a play for the House of Commons, becoming Justin Trudeau’s culture minister. Bergeron abandoned his party to become a Coderre ally, sitting on the powerful executive committee at city hall. Côté, tragically, died of a heart attack while on a charity bike ride.

This time around, Coderre was expected to win handily.

Enter Plante. The one-time city councillor was a political nobody. Her name didn’t register on opinion polls. She barely won her party’s own leadership race. She was counted out from the very start. Her campaign pitch was a lot of bread-and-butter stuff for a left-wing municipal campaign : more bike lanes, urban agriculture, affordable housing, streamlined construction, pedestrian-friendly streets.

All of these things have been core to Projet Montréal, which was founded in 2004 but which never did better than third place in a mayoral campaign. While their platform often went over well in the city’s trendy Plateau neighbourhood, it struggled to break through with families living outside of the downtown core. Until this election.

Montreal currently sits in a very interesting spot. An aggressive anti-corruption crusade on every front—including Coderre’s administration—has achieved incredible progress in ousting the backroom dealers who turned Montreal city hall into their own private ATM. Despite the city’s reputation for stalled construction, Montreal’s roads and parks are looking made-over and refreshed. Quebec’s economy is booming, and its largest city is showing the benefits. Housing prices remain low and there’s a stock of affordable rental units, enough to make blood boil in Toronto and Vancouver.

Montrealers are regaining their modest confidence, and it shows. The city is bustling, its culinary scene remains the best in the country, its bars are more fun, its art scene is thriving. Mix that optimism with simmering frustration with Coderre’s style of retail politics—one that wasn’t above dumping millions into flashy parties in order to gin up support—and Montrealers were set to take a pretty big gamble on Plante.

Plante is a painfully charming iconoclast. She’s bubbly, self-effacing, plain weird. During her victory speech on Sunday night, she was bouncing around the stage, uproariously laughing, waving at friends in the crowd, deviating from her script for excited asides. She was exactly as she had been during the whole campaign: impossibly likeable.

As her charm offensive began to make inroads with the public, she leaned into her quirky appeal. Signs went up across the city advertising Plante as the next mairesse de Montreal. On the posters, Plante stands, arms crossed, next to her slogan: “L’homme de la situation.” The man for the job.

An arguable turning point in the race was the two candidates appearances on Tout le monde en parle, an incredibly popular talk show that has made and broken political careers. Coderre, out of the gate, was defensive and gruff—he immediately pushed aside the glass of wine that is a hallmark of the show. Plante, next to him, was effortless, relaxed, likeable, even as she roasted him over his four years in office.

I spent election night in Montreal at a tequila bar in up-and-coming, yet still working-class, Saint-Henri neighbourhood. There, Tyler Lemco—internet personality and sort-of joke mayoral candidate—was having his election party. He came dead last, with just over a thousand votes. And yet, he got a text from Plante, mayor-elect, inviting him out for coffee. Lemco seemed as excited as anyone else in the bar that she had won.

Plante benefited from Coderre’s missteps. His administration pumped an electric-vehicle race, the Formula E, that was widely regarded as a bust—some 40 percent of the tickets had to be given away for free. Then there was the pit bull ban, an effort to phase out an entire breed, that incited animal lovers and dogged Coderre the entire race. Then it was also revealed that many of the construction firms implicated in Montreal’s shady corruption schemes were still getting lucrative city contracts, although often with new names and branding.

It wasn’t the headline-grabbing audacious corruption that had felled many of Coderre’s predecessors, but he gained a reputation as an old-school politician who was not above buying the public vote.

That alone wasn’t enough to oust Coderre, however. At the core of Plante’s campaign was her own massive gamble. She was promising a whole new metro line: the pink line. It would intersect lines on Montreal’s already-impressive subway system, connecting low-income communities with the downtown core. Its stations would be named for Québécoise icons. Even if the public is skeptical of and cynical about the pink line, it nevertheless tapped a nerve: the city wanted a big plan. Something bold.

On its face, it’s hilariously unworkable. Montreal hasn’t built a new subway line in thirty years. It would take too long. It would cost too much. It would never get done. And yet, Plante came up with a perfect pitch. She would draw from the federal infrastructure bank, the fund set up by the Trudeau government to underwrite big-ticket municipal projects. It’s a $35 billion fund for, as Ottawa puts it, “transformative infrastructure projects.” The money for the $6 billion line would, Plante promised, come from Trudeau.

The new mairesse is not without her weaknesses. She’ll be leading an administration with virtually no experience running an entire city, much less a city hall renowned for its shady politics and its dark money. Some of her policies may be simply unfeasible, and she may end up spending more time climbing down from her pledges than actually implementing them.

There is already a sense that Montreal’s business community, which feels downtrodden in the high-tax city, isn’t going to be comfortable with Plante’s urbanist administration—so much so that Plante made a specific pitch to them during her speech on Sunday night, insisting, in English, with some degree of urgency: “Montreal is open for business.”

But with her victory alone, Plante, in typical Montreal fashion, may be an instructive trend for the rest of the country.

Quebec’s GDP growth, at 2.9 percent, is the highest it has been in fifteen years; its unemployment rate, 6.1 percent, is below the national trend; and the province’s books have been balanced for years. Quebec may be ahead of the country in economic growth at the moment, but the rest of Canada—after nearly a decade of recession, austerity, and anemic growth—is catching up.

Montreal is undeniably unique—its bars are open later, its bagels are thinner, its culture is perplexingly cool and unassuming—but Plante’s earnest victory may be a sign of things to come for upcoming municipal elections in Toronto and Vancouver. Mix in the fact that Trudeau has pitched an infrastructure bank that is seemingly tailor-made for ambitious municipal weirdos like Plante, and you may see her imitators cropping up everywhere.

Even failing that, the table of Canadian mayors just gained a new homme de la situation.