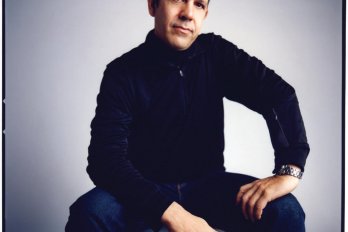

When Stephen Harper stepped up to the podium at the Conservative party’s convention in Winnipeg last November, the grassroots members were expecting a triumphant pep talk. He delivered. This was the party’s second convention. At the first, in Montreal in 2005, he had arrived as the Opposition leader, with little chance of defeating the Liberals. Now he was back before them as the prime minister of Canada. They basked in his aura.

The Conservatives had returned to power with an increased plurality. True, a setback in Quebec had kept the government to a minority. But outside that province, where they had won 133 seats to their opponents’ 100, they were now the undisputed majority party. The Liberals, their constant adversaries since 1867, had been crushed, humiliated, deserted by long-time supporters, and were now stuck with a lame-duck leader in Stéphane Dion. Despite the economic storm gathering over the country, for the Tories the future looked bright.

Harper’s speech, more than a cry of victory, suggested the Exodus story, set in Canada. The Conservatives had wandered in the wilderness. Now they had fought their way back to the promised land. “The Conservative party is Canada’s party,” he announced. This proud claim became his leitmotif, the counterpoint to the travails his people had known.

“As we gather together here as a party, let us pause for a moment, and truly reflect and appreciate how far we have come, in so short a time,” he told his supporters. “Five years ago, the Conservative movement in this country was divided, defeated, and demoralized. The government of the day ridiculed us. The pundits discounted us. And the public said, ‘Don’t bother talking to us until you’ve got your act together.’”

Two former warring parties, the Canadian Alliance and the Progressive Conservatives, had united under a new vision, which had led them through the desert. Harper enumerated its tenets: “Lower taxes and prudent spending focused on the priorities of Canadians. A commitment to free enterprise, free markets, and free trade. La croyance en un gouvernement plus responsable, plus transparent. A justice system that puts the welfare of law-abiding citizens before the interests of criminals. Strong support for rebuilding this country’s too-long-neglected Canadian Forces. An unwavering commitment to asserting our sovereignty over the Arctic. A belief in a foreign policy that is both strong and independent. And a passionate belief in the unity of this country!” These were the principles that Harper had long fought for; now they were embraced by a mainstream party. His party and Canada were moving closer together, and closer to him.

Not so long ago, the Conservatives had been considered ideological aliens, outside the pale of Canadian values. But things had changed. “We made important inroads with women voters and with new Canadians,” Harper reminded them. “From Comox to Iqaluit to Summerside, we painted large swaths of this great country Tory blue. Because, friends, the Conservative party is once again Canada’s party!”

His exuberance, although understandable, was overstated. True, only the Conservatives were strong in almost every corner of the country. But their share of the vote was only 37.6 percent. Their 143 members in the Commons improved on the 124 of 2006, but Canadians had also returned 165 MPs from other parties: 77 Liberals, 49 members of the Bloc Québécois, 37 New Democrats, and two independents. The Conservatives remained weak in the largest metropolitan centres: Toronto, Montreal, and Vancouver. The country was still a rainbow, not Tory blue.

But Harper was already looking to the future. He had come to elected politics reluctantly, only because he believed that something was terribly wrong with the country, and that its elites were blind to the danger. Derided at first, he had seen Canada gradually move closer to the vision he’d formed in the wilderness. The Conservatives were still poised for a breakthrough, if Harper could stay the course, continue to learn from his mistakes, and adapt. A steady hand on the economy, a new strategy in Quebec, and next time the majority would be theirs. If they weren’t yet Canada’s party, they would be soon.

It would be a challenging task. Harper had always been something of an outsider, unable to bend to conventional wisdom. His vision for the country had been forged in isolation, his political life guided by conviction—and in conviction lies the potential for overreach.

Growing up in the Toronto suburbs of Leaside, then Etobicoke, in the 1960s and ’70s, Stephen Harper was an unlikely prospect for prime minister. At Richview Collegiate Institute, he was renowned for his “very reserved and private manner,” in the words of Bob Scott, his grade thirteen history teacher. As a student, he was both inner directed and brilliant. His friend Larry Moate described a stellar intellect: “Stephen was smart in the humanities, math, science. Anything he wanted, he excelled at.” Tall, thin, and asthmatic, Harper eschewed team sports, preferring long-distance running. He took piano seriously and reached the grade nine level at Toronto’s Royal Conservatory of Music.

His family was close knit. His mother, Margaret, stayed at home, raising Stephen and his younger brothers, Grant and Robert. She and the boys’ father, Joseph, had met at Danforth United Church and were married in 1954. Joseph had come to Toronto from the Maritimes, home of his ancestors since 1774. A chartered accountant who worked for Imperial Oil, he collected jazz music and wrote books on Canadian military history in his spare time. Both Grant and Robert became chartered accountants, which once prompted Stephen to joke, “I was under a lot of family pressure to become a chartered accountant, but I became an economist and a politician. They concluded I didn’t have the charisma to be an accountant.”

At the end of grade thirteen, he was awarded Richview Collegiate’s gold medal for the highest marks. But then a strange thing happened: the brilliant student dropped out of the University of Toronto after only a few weeks, and moved to Edmonton to take a job in Imperial Oil’s mailroom. His parents were dumbfounded. His father had always regretted not being able to attend university. Margaret tried to dissuade Stephen: “I told him that if he dropped out of university he would never go back.”

That would be Stephen Harper’s way. He could not do what was expected of him, could not think what everyone else thought. He had to find his own way, think things through for himself, find himself, then follow his own star. It would lead him along an unlikely path.

He wasn’t even thinking of politics when he enrolled at the University of Calgary three years later to study economics. World affairs were his interest, and he had thoughts about serving Canada as a diplomat. A counsellor advised him to beef up his CV by participating in a community activity, so, almost by chance, he joined the Progressive Conservative association of his Member of Parliament, Jim Hawkes.

In high school, Harper had admired Pierre Trudeau, and had even signed up for a student Liberal club. But after moving to Alberta and seeing the devastation done to the province’s economy by Trudeau’s National Energy Program, he changed his allegiance. Disenchanted with his former idol, he would write, “In 1977, economics and finance didn’t much matter to me. Beginning with the nep, Mr. Trudeau would show me that they did matter—a lesson he never bothered to master himself.”

After Harper completed his bachelor’s degree, Hawkes invited him to Ottawa to work as his legislative assistant. Witnessing the Mulroney government’s fiscal irresponsibility, Harper soon became disenchanted. He abhorred the posturing and adolescent antics he saw daily in the Commons, and the influence special interest groups had on governance. At one point, he assisted a Commons committee, chaired by Hawkes, that was conducting a review of the unemployment insurance program. The Royal Commission on Canada’s Economic Prospects had just presented its final report, criticizing Canada’s UI program for encouraging youths to drop out of school and workers to choose seasonal jobs. This conclusion was subsequently confirmed by two other commissions, one appointed by Brian Mulroney, the other by Newfoundland’s premier, Brian Peckford. All three recommended separating the intended insurance function (against sudden unemployment) from what was really disguised welfare for seasonal workers.

Instead, Hawkes’s committee proposed the exact opposite: further extending unemployment insurance to other vulnerable social groups. The experience turned Harper off federal politics. So, a year into his time in Ottawa, he returned to the University of Calgary, leaving the security and assured success he could have enjoyed in the governing party. His plan was to become a public intellectual, offering dispassionate analysis and advice to politicians and the public.

By the fall of 1986, Harper, now twenty-seven, began work on his master’s degree. He set himself the task of systematically reading all the major works on political economy, past and recent. He was joined in this by John Weissenberger, a student from Quebec then working on his Ph.D. in geology. Their friendship had begun a few years prior, when both became active in PC politics. They met twice a week for Chinese food at a mall across from the university, where they would discuss and exchange the books they were reading. “We were both philosophical conservatives, and we were both interested in public policy,” Weissenberger later recalled.

Besides classics, they read William F. Buckley’s 1951 conservative shocker, God and Man at Yale, and his 1959 follow-up, Up from Liberalism. They read theologian Reinhold Niebuhr, a former socialist converted to conservatism. And they absorbed Austrian Nobel laureate Friedrich Hayek’s seminal work, The Road to Serfdom, which inspired a generation of neo-conservatives. Hayek had experienced the turmoil in central Europe after Germany’s defeat in 1918 and the rise of communism and fascism. He denounced the newly popular nanny state as a threat to both freedom and prosperity. Central economic planning led to failures, which led to more planning and hence more state control.

Harper and Weissenberger were also impressed with Peter Brimelow’s The Patriot Game, in which the former business editor of Maclean’s cast the obsession with placating Quebec as the futile governing principle of Liberal politics in Canada. Since Harper’s birth on April 30, 1959, just a year before the outbreak of Quebec’s Quiet Revolution, the province’s alienation from Canadian federalism had indeed been the dominant concern of Canada’s national politics. “What does Quebec want? ” was the country’s central existential question, and no answer had ever proved adequate.

Harper’s sense of identification with the West escalated in the fall of 1986, when Brian Mulroney announced that a new fleet of 138 cf-18 fighter planes would be serviced by Montreal’s Canadair rather than Winnipeg’s Bristol Aerospace. The awarding of the $1.2-billion contract, which contradicted the recommendation of the government’s own experts, sparked indignation across the prairies. Mulroney’s minister of energy, Pat Carney, later wrote in her memoir, Trade Secrets, that the decision “changed Canadian history by hardening western alienation, breathing life into the Reform movement and bringing on the slow death of the Progressive Conservative Party.”

Harper and Weissenberger were at the time planning a “Blue Tory network” within the PC party that would move the party to the right, but the cf-18 fiasco made them despair of the possibility of internal reform. Then, at an informal economics department meeting, they met Preston Manning.

In May of 1987, Harper found himself in Vancouver for the Western Assembly on Canada’s Economic and Political Future, held under a banner proclaiming The West Wants In. He had prepared a paper with Weissenberger that sat on a table at the back of the room. Entitled “A Taxpayers Reform Agenda,” it expressed a commitment to “strong conservative principles.” It urged, for example, that activist government must be countered by bringing to bear the views of the taxpayers, and advocated “the implementation of the new economics—of smaller government, regional diversification, non-discriminatory or discretionary spending, privatization, fair trade, and less expensive and less bureaucratic income transfers.” It also opposed the constitutional amendments accepted three weeks earlier by the first ministers meeting at Meech Lake. It contained no trace of social or religious conservatism.

The assembly voted to found a new party, and Harper attended the founding convention in Winnipeg as a featured speaker. “This paper is about justice and injustice, about fairness and unfairness, and about compassion and selfishness, in the economic treatment of western Canada under Confederation,” he began. Using facts and figures, he laid out how Alberta and the West had been plundered. He was given a standing ovation, prompting the Alberta Report to comment, “The speech was acknowledged by delegates, party officials, and media as a highlight of the convention.” Manning soon named Harper the Reform Party’s chief policy officer; they alone were authorized to speak in the name of the party.

The media was immediately patronizing toward Reform. Delegates woke up on November 1 to a story in the Toronto Star by Val Sears that treated them like spooks: “winnipeg—A broomstick load of revolutionary ghosts rode Winnipeg’s Halloween sky last night, summoned by the West’s newest political bloc, the Reform Party of Canada.” The memory of the new party’s treatment by the country’s political establishment would stay with Harper. Still, it confirmed the beginning of a new phase of his life. He was developing a vision, a mission, and now had a vehicle for implementing them.

From that time on, Harper would be in the public sphere. He decided to run in the 1988 federal election as a Reform candidate in Calgary West, against his old mentor, Jim Hawkes. Quebec was one of his greatest concerns at the outset. In his nomination speech to the constituency association, he explained that he had turned against the policy of official languages. Mulroney had put Lucien Bouchard, the ardent separatist and promoter of Quebec as a French-only jurisdiction, in charge of the file. “Many are like me,” Harper said, “individuals who once supported official bilingualism but now realize that federal language policy is collapsing under the weight of its own hypocrisy.” A few years later, he would famously write, “As a religion, bilingualism is the god that failed. It has led to no fairness, produced no unity, and cost Canadian taxpayers untold millions.”

Harper and his party both went down to defeat. He soon started strategizing for the next election, laying out a vision for Reform that placed him somewhat at odds with the organization he had only recently helped create. On March 10, 1989, he sent Manning a confidential twenty-one-page memo that brazenly challenged his leader’s most cherished assumptions.

Manning was a populist, Harper a conservative. Manning envisaged his party surging to power as part of a movement that animated a whole people, on the model of Social Credit’s ascent to power in Alberta in 1935. He wanted Reform to draw support indifferently from Tories, Liberals, and New Democrats. In a “leader’s foreword” to the 1988 election platform, he had written, “We reject political debate defined in the narrow terminology of the Left, Right, and Centre.” He looked for support not in the big cities, but in the hinterland. So committed was he to this vision that he insisted on a sunset clause in Reform’s constitution: if the party had not achieved power by the year 2000, it would be dissolved, barring a contrary vote from two-thirds of its members.

As a conservative, Harper wanted a long-term, patiently constructed, permanent party that would build coalitions of economic and social conservatives to form a government. Unlike Manning, he believed Canada needed the kind of ideological polarization and political realignment exemplified by Margaret Thatcher in the UK and Ronald Reagan in the US. This would mean a conflict between the ever-burgeoning public sector and the overtaxed urban middle class of the private sector. “It was a battle,” he wrote in his memo, “not only for tax dollars, but about social values and social organization, especially over the size and role of government.”

Around this central axis of political conflict, Harper saw secondary alignments based on interests and values. Whole sectors of society, even regions, benefited from state subsidies. The “political class” tended to be liberal on such issues as crime, unconventional lifestyles, and family values, while the working and rural classes tended to be “outrightly hostile to the liberal intellectualism of the Welfare State class.” He proposed that the Reform Party become a political movement that would defend the private sector and moderate social conservatism. Only when economic and social conservatives worked together could a right-wing party take power in Canada.

That same month, Reform gained its first seat in Parliament, winning a by-election in the central Alberta riding of Beaver River. Manning prevailed on a reluctant Harper to suspend his studies for a year in order to assist the new member, schoolteacher Deborah Grey. Once again back in Ottawa, he witnessed the death throes of the Meech Lake Accord and the attendant surge of separatism in Quebec. Later, he devised Reform’s strategy for opposing the 1992 referendum on the Charlottetown constitutional accord. As with Meech, the establishment denounced and derided Reform’s opposition, but most Canadians supported the party’s stance.

When the 1993 federal election was called, Harper again ran in Calgary West, again expecting to lose. But the country turned mid-campaign against the new government of Kim Campbell, who had inherited Brian Mulroney’s legacy of distrust—a country polarized, region against region. The Mulroney government had also run eight deficits in a row and more than doubled the national debt.

Harper had warned for years that the nation was at risk of hitting a wall, and now led the team that crafted Reform’s chief policy plank for the election, called Zero in Three. Its central proposal was to eliminate the $36-billion deficit within three years by cutting $18 billion in federal spending. Jean Chrétien’s Liberals accused the Reformers of a slash-and-burn policy that would drive the country to ruin, and promised instead to merely diminish the deficit rather than eliminate it.

The election reduced Campbell’s party to two seats. The Liberals took power, and fifty-two newly minted Reform MPs, including Harper, took their seats across the aisle. Soon, the Liberals became aware that the country was in danger of a fiscal crisis. As Paul Martin recounts in his memoir, Hell or High Water, international investors, spooked by the Mexican peso crisis, “began looking around for other vulnerable countries with unresolved fiscal problems, and we were near the top of the list.” Martin’s 1995 budget brought the deficit down to zero in three years, and subsequently produced budget surpluses. He made deeper spending cuts than Zero in Three had proposed, without spinning the country into turmoil. This would be the Chrétien-Martin government’s proudest achievement—but it was Reform that had first foreseen the crisis and proposed the solution. And it was the party’s support in the Commons that made eliminating the deficit politically feasible. Martin’s greatest success in fact implemented Stephen Harper’s earlier vision. This was the country’s first big step toward what Harper stood for from the start.

The other imminent threat to the country was the ascent to power of the Parti Québécois on a pledge to hold a referendum on secession. On December 6, 1994, Premier Jacques Parizeau unveiled a draft bill that stated in section 1, “Quebec is a sovereign country.” Unlike René Lévesque in 1980, Parizeau was going for unilateral secession. Immediately, the Reformers challenged the referendum’s constitutionality. That very evening, Harper declared on a cbc television panel, “The Parliament of Canada and Canadians cannot be stripped of their power, and a province cannot redefine its constitutional status as Mr. Parizeau asserts, without any reference to the rest of the country or its legal rights and obligations. I think it’s very important that a clear message be sent out that that will not happen.”

And yet Prime Minister Chrétien evaded, wavered, and waffled. He objected primarily to the formulation of Parizeau’s referendum question, not its legitimacy. On referendum night, October 30, 1995, Parizeau carried more than 49 percent of the vote, coming within a heartbeat of precipitating the worst existential crisis in Canada’s history. Harper soon introduced Bill C-341, the Quebec Contingency Act (Referendum Conditions), which laid down stringent conditions for Quebec to secede. Years later, in 1998, the Supreme Court of Canada delivered its response to the reference on secession, spelling out a doctrine that vindicated Harper’s vision. When the Chrétien government finally passed the Clarity Act, in 2000, it fell short of Harper’s bill, failing to lay out what the government would do if Quebec passed a unilateral declaration of independence—the most likely path of secession.

Characteristically, Harper didn’t complete his first mandate as a member of Parliament. In January 1997, he dropped out to take a position as vice-president (later president) of the National Citizens Coalition, where he could agitate for policies concordant with the organization’s slogan: “More freedom through less government.” His decision stemmed mainly from differences between his and Manning’s visions. He had gone public with his views in the spring of 1995, in a Globe and Mail article with the headline, “Where Does the Reform Party Go from Here? To be credible as the logical alternative to the Liberals, says a Reform MP, the party can’t just fight elections on the popular protests of the day.” When his plea to Reform’s rank and file failed, Harper quit.

He returned to electoral politics only when his conservative vision was threatened by the leadership of Stockwell Day. Manning morphed the Reform Party into the Canadian Alliance in 2000, attracting a fringe of Progressive Conservatives. But in 2001, thirteen Alliance MPs left the caucus to sit with Joe Clark’s Progressive Conservative MPs. Day called a leadership convention to settle the strife, but most of the candidates favoured uniting the Alliance with the PCs. This would have meant a shift to the left, as long as Joe Clark, a Red Tory, was their leader.

So Harper ran for the Alliance leadership, and on March 20, 2002, took over a party that was battered, broke, and discredited. In the Toronto Star, Richard Gwyn dismissed him as “yesterday’s man.” Edward Greenspon, now editor-in-chief of the Globe and Mail, described him as an ideologically displaced person in Canada: “Stephen Harper: A Neo-con in a Land of Liberals.” The Vancouver Sun wrote, “He presents himself as unbending, unwilling to make the compromises to appeal to the middle-of-the-road voters and traditional supporters of the Progressive Conservatives.”

Perhaps so, but in just two years Harper restored the Alliance’s unity and finances and merged the party with the Progressive Conservatives. He won the leadership of the new entity, then was thrust almost immediately into the 2004 election, which was called by Paul Martin before the new party could get organized. Lacking the time to hold a policy convention, the Conservatives couldn’t craft a ratified program, and Martin was therefore able to define the party as he chose.

He portrayed their leader as scary. Harper had a hidden agenda. He was an American-style conservative who would destroy medicare and demolish the social safety net that protected the poor, the unemployed, and the disabled. He would strike down women’s right to abortion and probably bring back the death penalty. This complex of messages was compressed into one slogan: “Harper is another George Bush.” It didn’t help that other Conservative candidates affronted progressive public opinion during the campaign—one, for instance, equated homosexuality with pedophilia.

In reality, Harper was not a social conservative, and had differed on social issues even with the Reform Party. During Reform’s annual assembly in October 1994, the party had tabled the following motion: “Resolved, that the Reform Party support limiting the definition of a legal marriage as the union of a woman and a man, and that this definition be used in the provision of spousal benefits for any program funded or administered by the federal government.” Manning supported the resolution, and the convention voted 87 percent in favour. But Harper protested: “Those are not partisan issues; those are moral issues. People have to be able to belong to political parties regardless of their views on those issues. It’s perfectly legitimate to have moral objections as well as moral approval of homosexuality, but I don’t think political parties should do that.” His judgment was far-sighted. Had he prevailed, Reform and its successors would have been spared much future strife and public distrust.

Despite the obstacles, the Conservatives reduced the Liberals to a minority. At the party’s first convention, in 2005 in Montreal, Harper urged it to adopt a moderate program. A resolution condemning abortion was subsequently defeated, and Harper promised never to introduce a bill on the issue. After the convention, he insisted on strict adherence to the official program—nothing more, nothing less.

During the 2006 election campaign, he imposed an unprecedented control on his candidates: if they spoke publicly, they had to stick to the program. Harper knew he was mistrusted, and that the Liberals would again paint him as scary, so he focused his campaign not on himself, but on a daily unveiling of goodies that targeted broad clusters of voters. The Martin Liberals had expected him to announce a platform of spending cuts. Instead, he matched their cornucopia of spending promises with policies that were as much populist as conservative. He countered the Liberals’ pledge to cut income taxes by offering to reduce the gst by two points, for example, and countered their program of subsidized public daycare with a subsidy of $100 a month for every child under the age of six. The policies were designed to appeal to as many Canadians as possible, and they succeeded.

And so it was that on January 23, 2006, Stephen Harper became prime minister.

Once in the job, Harper demanded an iron discipline from his cabinet and caucus. Recognizing that neither he nor any of his ministers except Rob Nicholson had experience in a federal cabinet, he became a control freak, restricting the public utterances even of caucus members. Whatever was not official doctrine could not be freelanced without prior permission from the Prime Minister’s Office. Harper placed controls on journalists’ access to ministers and information, engaging in a constant power struggle with the press gallery. Miraculously, there was no revolt, and he was able to keep Conservative MPs almost entirely out of serious trouble.

All of this contributed to the perception of Harper as a rigid, controlling personality—an impression exacerbated by the bullying he inflicted on Stéphane Dion, who was in no condition to lead his penurious Liberals into an early election. Harper, contrary to tradition, turned a range of bills into confidence votes, on such issues as reforming immigration rules or toughening laws on crime and punishment. The Liberals, shamefaced, were frequently forced to abstain from voting rather than bring down the government. Harper then taunted them for their weakness.

As prime minister, he devoted more time and blandishments to seducing Quebecers—the key to the Conservatives’ prospects for a majority—than to any other objective. He knew he was distrusted for his past criticisms of the Official Languages Act, and for his opposition to the Meech Lake and Charlottetown accords and the premiers’ 1997 Calgary Declaration. But during the campaign for the 2006 election, he attenuated his objections to some nationalist articles of faith, and then, after he was in office, celebrated French as Canada’s founding language. After promising a “federalism of openness,” he gave Quebec a voice in the Canadian delegation at unesco, turned over billions to settle the “fiscal imbalance,” recognized Quebec as a nation within a united Canada, and routinely began his speeches in French. This would provide his greatest achievement: in the Quebec provincial elections of 2007 and 2008, secession was almost ignored as an issue.

At the outset of the 2008 campaign, polls showed Harper to be Canadians’ preferred choice as leader. So this time the Conservatives’ campaign was more personal, focusing on Harper as the best manager for the country during threatening economic times. He was shown in ads as a kindly, solicitous dad in a navy blue sweater vest. No longer the outsider, he was positioned as a father, a family man like any other. The strategy largely succeeded outside Quebec. In that province, the Conservative campaign was dominated by the announcement of $45 million in cuts to certain arts programs, which provoked Quebec’s intellectual and artistic communities to mount a spectacular campaign that presented the Conservatives as being at war with Quebec’s culture and very identity.

Following the October 14 election, which returned the strengthened Conservative minority, Harper invited the other party leaders to work with him, and promised to be flexible. As he told his followers in Winnipeg, “We will have to be both tough and pragmatic, not unrealistic or ideological, in dealing with the complex economic challenges that confront us.” The g-20 nations, meeting in Washington the next day, called for massive government spending to reverse the accelerating worldwide economic decline. Harper concurred, and even acknowledged that the Canadian government would likely have to incur budget deficits—a move he had disavowed during the campaign.

But then, on November 19, the celebrated strategist made a monumental blunder: he presented the country with a Throne Speech that sounded like a summons to austerity. “Hard decisions will be needed to keep federal spending under control and focused on results,” the Governor General read. “Departments will have the funding they need to deliver essential programs and services, and no more.” Taken on its own, this position was defensible enough. In the United States, Barack Obama was warning that to spend massively in some areas, the government would have to cut back in others, in order to avoid structural deficits. But Harper made two mistakes. The first was deciding to split his economic program into two parts, announcing the bad news of spending cuts on November 27, in Finance Minister Jim Flaherty’s fiscal statement, while remaining silent for the moment on measures to stimulate the economy and bail out failing industries.

The second mistake: rather than consulting with the other party leaders on an economic plan that could mobilize their support, he once again acted as if he had a majority, placing his vision above sound politics. Cutting fat in government programs had always been a Conservative objective, and the threat of a grave economic crisis was an ideal reason for belt-tightening. But Flaherty’s statement contained so many right-wing announcements that it stunned the opposition parties. “Our government expects to save over $15 billion over the next five fiscal years under the new expenditure management system,” he declaimed. “This system will be an invaluable tool to help us maintain balanced budgets, along with the other steps announced today.”

Balanced budgets? When the economy needed stimulus? One of the “other steps” was a three-year ban on wage-related strikes in the federal public service, meaning that wage increases would henceforth be set by decree rather than collective bargaining. Another was to remove pay equity from the purview of the Canadian Human Rights Commission, making it instead a matter to be negotiated through collective bargaining. But what really set the cat among the pigeons was the announcement that the political parties would lose the $1.95 they were granted annually for each vote received in the previous election. The measure was seen across the country as a mean, wholly partisan attack. Everyone knew that the Conservatives alone were fundraising effectively at the grassroots.

And yet the move also coincided with Harper’s strategic vision on Quebec. The Bloc had won forty-nine of the province’s seventy-five seats, demonstrating that Quebecers remained alienated from the federation despite everything he had done to win them over. Furthermore, from the Conservatives’ perspective the federal government had been subsidizing separatism. Like the other parties, the Bloc received $1.95 per vote, but unlike its competitors it did not have to rent planes to fly to Victoria, Iqaluit, or St. John’s. It campaigned only in Quebec and only in one language. Its costs were low. And it could work in tandem with the Parti Québécois, which receives fifty cents per vote under Quebec’s provincial system.

Targeting the Bloc, though, would also damage the Liberals and the ndp, as Harper well knew. He ultimately withdrew the proposals to eliminate political subsidies and public servants’ right to strike, and announced that bailouts and stimuli were coming—but it was too late. The three opposition leaders had taken Flaherty’s fiscal statement as a declaration of war, forming a coalition that sought to topple the Conservatives immediately and replace them with a Stéphane Dion–led Liberal-ndp government, supported by the Bloc Québécois. The coalition would be able to muster 163 votes in the House, compared with the Conservatives’ 143.

Harper fought back, first postponing the confidence vote he’d planned for December 1, then denouncing the coalition in terms akin to treason: “The highest principle of Canadian democracy is that if one wants to be prime minister one gets one’s mandate from the Canadian people and not from Quebec separatists. The deal that the leader of the Liberal party has made with the separatists is a betrayal of the voters of this country, a betrayal of the best interests of our economy, and a betrayal of the best interests of our country, and we will fight it with every means that we have.”

Polls showed that the coalition was widely viewed as illegitimate. None of the three opposition leaders had campaigned on a coalition; on the contrary, all had explicitly rejected the possibility. It appeared that the election results would be overturned by politicians seeking partisan advantage, in response to a prime minister who appeared to many to be doing the same. In an extraordinary televised address to the nation on December 3, a combative Harper vowed, “Tonight I pledge to you that Canada’s government will use every legal means at our disposal to protect our democracy, to protect our economy, and to protect Canada.” Duceppe, in reply, began, “The Bloc Québécois is a party devoted exclusively to the service of the Québécois.” He could have added “and to the objective of Quebec’s separation.”

The following day, Harper met Governor General Michaëlle Jean, who consented to his request to prorogue Parliament until January 26. The vote of confidence was in abeyance.

No one came out of this tragicomic episode looking innocent, but as in past battles Harper showed a more sound appreciation of the public interest than did his opponents. An Ipsos Reid poll published December 5 showed that 61 percent of Canadians supported the elimination of the $1.95 subsidy—the issue that had sparked the opposition parties’ furor in the first place. The threat to national unity had emerged not from Harper’s provocation, but from the coalition, which would have imposed on Canada an incoherent, unstable, and illegitimate government, with Gilles Duceppe as the kingmaker. When polls made it obvious that Dion had grievously misjudged the situation, he resigned and was replaced as leader by Michael Ignatieff, whose support for the coalition had never been more than lip service. The crisis was over, at least for a time.

Still, the country had become needlessly mired in partisan politics on Harper’s watch. His dogged pursuit of his vision, however sage that vision might have been, had left the country dug in on all sides at a moment that demanded consensus. If, as he claimed, the Conservatives were Canada’s party, they had still further to travel in proving it. And Harper himself, who usually learned from his errors, would have to take lessons in the politics of consensus.