Listen to an audio version of this story

For more audio from The Walrus, subscribe to AMI-audio podcasts on iTunes.

Just before noon on a warm Wednesday in August 2019, Marilynn-Leigh Francis slowed her boat down and looked out across the water. The buoy wasn’t there. She sat at the bow, held the wheel, and considered the currents. An army-green baseball cap shielded her eyes from the sun. It was almost high tide, and the strong pulls in the Bay of Fundy had likely made her lobster traps disappear, hiding them beneath the ocean’s surface. As she’d hoped.

“See?” Francis called back to her friend. “Tide’s pulling our buoy down.”

“I was gonna say.” Tiffany Nickerson was perched on an empty trap at the stern of the small skiff. It was her second day out fishing with Francis.

The Mi’kmaq have fished these waters, along the coast of what is now Nova Scotia, for millennia and have called this place home for just as long. Francis, like Nickerson, is Mi’kmaw, and she was teaching her friend how to catch lobster.

From the boat, the port town of Yarmouth, Nova Scotia, appeared in miniature. Like it is to so many coastal communities in the Maritimes, lobster is part of the local DNA: along the town’s main strip, shops sell nautical kitsch—smiling cartoon lobsters drawn on cards, mugs that say “work like a captain, play like a pirate.” Tourists pass through the port and nearby coastal towns to eat at restaurants with names like Captain’s Cabin or The Crow’s Nest. Diners pick lobsters from tanks and don plastic bibs to catch the splatter when they crack open the shells.

Lobster is Canada’s most valuable seafood export. And the sea around southwestern Nova Scotia, or Kespukwitk, where Francis fishes, is one of the largest and most lucrative lobster-fishing areas in the country. (Kespukwitk is one of the seven districts that make up the vast Mi’kmaw territory of Mi’kma’ki.) Federal law requires all fishers to operate with a licence. But, like many Mi’kmaw fishers, Francis and Nickerson assert that they don’t need one. Which is why Nickerson has to learn about more than just how to set traps.

“I wonder if DFO got it,” Francis said to her friend as her boat rocked on the waves. Francis checked the location on a GPS device hanging from a cord around her neck.

It wouldn’t be the first time officers from Fisheries and Oceans Canada, commonly known as the Department of Fisheries and Oceans (DFO), had hauled Francis’s traps out of the water and locked them up in a fenced-off compound. Francis was fishing without a licence that day, as she always does. She was also fishing in August, three months before the start of the DFO-regulated season. After providing for her family and giving some of her catch to Elders in her community, Francis usually trades or sells the rest. To the DFO, that’s another affront: without a commercial licence, any sales or trades, however small, are considered illegal.

The DFO regulates fishing in oceans, lakes, and rivers in Canada, which includes determining—and enforcing—who can fish when, where, and how much they can catch. The department issues fishing licences and decrees, among other things, the start and end of lobster-fishing seasons. Officials schedule the seasons around factors such as when the crustaceans breed and moult and when their new shells have hardened enough to preserve the meat inside. In the waters where Francis drops her traps, the lobster season usually runs from the end of November until the end of May.

Fisheries officers police the waters and shorelines to try to catch fishers they accuse of fishing and selling lobster illegally. Many Mi’kmaw fishers, including Francis, assert that they have an inherent right to fish and make a livelihood outside Canadian regulations, a right that is enshrined in the treaties their nations negotiated with the Crown in the eighteenth century. In 1999, a Supreme Court decision, R. v. Marshall, confirmed Mi’kmaw people’s treaty rights to fish, hunt, and sell their harvests—but the federal government has yet to honour the ruling. Which is why, for the past two decades, the DFO and many Mi’kmaw fishers have been engaged in a seemingly endless loop of surveillance and countersurveillance operations. Despite having their traps and gear seized over and over, many Mi’kmaw fishers haven’t given up fishing on their own terms.

“No, I think the tide’s pulling it down,” Francis said. She had intended for her traps—or pots, as they’re often called—to be invisible to the officers who patrol these waters. And she wanted to drop some more before she and Nickerson called it a day.

Francis is from Acadia First Nation. She’s thirty-seven, about five foot six, and she often wears a ribbon skirt made from camouflage fabric (“because I’m always in battle”). She’s been fishing lobster since she was fourteen. According to Francis, the DFO’s official lobster season is “their season,” not hers.

“I’m gonna drop one right here,” Francis said to her friend. She tied a buoy to one of her traps.

Francis had labelled all her buoys with “Treaty 1752 Marilynn Francis,” written in black Jiffy marker. Nickerson watched as her friend pushed the trap over the side of the boat. The pot splashed as it hit the water. The treaty name, written on the white buoy, bobbed on the surface.

Fisheries officers have been known to go undercover, to slip out onto the water in the middle of the night to microchip lobsters in Mi’kmaw fishers’ pots in order to try to trace the shellfish. Less covert operations include seizing Mi’kmaw fishers’ traps, catch, boats, and even trucks. Sometimes it’s a handful of pots, like the twelve that Francis usually fishes. Other times, they seize hundreds of kilograms of lobster and drop them back into the sea.

Conflicts along the East Coast have been surging lately—and not just between Indigenous fishers and the government. Many non-Indigenous fishers have long accused Mi’kmaw fishers who operate outside the DFO’s regulations of poaching, fearing the toll on lobster stocks and, by extension, on their own catches and income. Like many Mi’kmaw fishers, they feel the federal government hasn’t done enough to address the Supreme Court ruling and bring clarity to treaty rights. With frustrations mounting over the past two decades, many Indigenous and non-Indigenous fishers and leaders have had enough. In a November 2019 article in the Chronicle Herald, a Nova Scotia paper, a non-Indigenous fisher described the rising tensions as “a loaded gun waiting to go off.”

Donald marshall jr. and his spouse, Jane McMillan, took turns pulling up nets and emptying eels into a small outboard motorboat in Pomquet Harbour, Nova Scotia. It was a bright August morning in 1993. They’d heard the eels that year were big and running well. Kat (“eel” in the Mi’kmaw language) are loved by Elders, to whom Marshall would give the best ones. The kat might be hung and dried or gutted for katawapu’l (eel stew).

While they checked their nets, a boat with armed DFO officers pulled up alongside them and asked to see their fishing licences. (All fisheries officers are trained by the RCMP and equipped with firearms, batons, pepper spray, and body armour.) Marshall told them that he didn’t need a licence because he was Mi’kmaw, from Membertou First Nation, recounts McMillan in her book, Truth and Conviction.

“Everyone needs a licence to fish,” one of the officers said to him.

“I don’t need a licence,” said Marshall. “I have the 1752 treaty.”

The officers wrote down Marshall’s and McMillan’s names and took a net as evidence.

The Treaty of 1752 is one of several treaties that Mi’kmaq Nation chiefs negotiated and signed with the British between 1725 and 1779. These treaties, often referred to as the Peace and Friendship Treaties, are based on sharing the land and trading and also included other neighbouring Indigenous nations. The Indigenous signatories and their descendants were promised the freedom to hunt, fish, and trade in exchange for an assurance that they would not “molest His Majesty’s Subjects.” The Treaty of 1752, in particular, was on Marshall’s mind that day because he knew that James Simon, a Mi’kmaw man, had used it in court just eight years earlier to defend his right to hunt. In Simon v. The Queen, in 1985, the Supreme Court wrote: “The Treaty of 1752 continues to be in force and effect.”

A few days after Marshall and McMillan were questioned by the officers, they sold the 463 pounds of eels they’d caught, at the going rate of $1.70 a pound, for $787.10. They went back out to the harbour to reset their nets. When they returned two days later, their nets and boat were gone. Later that fall, there was a knock at Marshall and McMillan’s door. Two fisheries officers had come to notify them that they were being charged with violating federal fishery regulations on multiple fronts: for fishing and selling eels without a licence, for using illegal nets, and for doing so after the DFO had declared the fishing season closed.

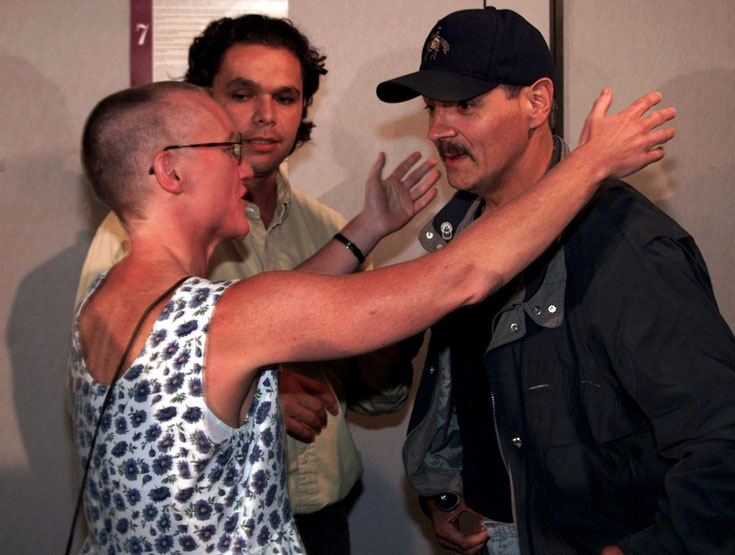

Marshall was forty, soft-spoken, and slender. His moustache was light brown, like his hair. And, by 1993, his name had already been in the news for years. In 1971, Marshall was sentenced to life imprisonment for a murder he didn’t commit. It was the first high-profile wrongful murder conviction in Canada to be overturned. After eleven years in jail, Marshall was acquitted. A Royal Commission on Marshall’s prosecution found that “racism played a part”—the miscarriage of justice, wrote the commission, was “due, in part at least, to the fact that Donald Marshall, Jr. is a Native.” Across Canada, Marshall’s name became synonymous with a flawed justice system.

Marshall’s eel-fishing case moved from one court to another. “I got sick a couple of times,” said Marshall, according to historian Ken Coates, who wrote about the case in his book Marshall Decision and Native Rights. “I thought I’d never be in this court again.” The charges against McMillan, who is not Indigenous, were dropped early on. It was clear to the first judge who heard the case that the trial was about more than fishing charges: it was a test case for Mi’kmaw treaty rights.

The Mi’kmaq have been pushing back against hunting and fishing restrictions for as long as can be remembered. In 1927, Mi’kmaq grand chief Gabriel Sylliboy was arrested for hunting out of season. He is believed to be the first to use the 1752 Peace and Friendship Treaty in court to fight for the protection of his rights to hunt and fish. Sylliboy was convicted of the charges, but after the Treaty of 1752 was upheld in Simon v. The Queen in 1985, his conviction was nullified. He was pardoned posthumously in 2017, almost ninety years after his conviction.

Marshall’s trial was watched closely. Thirty-four Mi’kmaw and Wolastoqi First Nations in Nova Scotia, New Brunswick, Prince Edward Island, and Quebec would be directly affected by the case. A verdict in favour of Marshall, affirming his treaty right to catch and sell eel, could be interpreted more widely. It could assert the treaty right to harvest and sell other fish, as well as game, plants, and trees, outside the Canadian government’s regulations. Indigenous people across the country wondered what legal precedent the ruling might set for them. News clippings often quoted Marshall saying he wasn’t going through with the hearing for his own sake: “I was there for my people.”

The trial moved slowly. Marshall’s legal team shifted its focus from the Treaty of 1752 to the Peace and Friendship Treaties of 1760 and 1761. These treaties outlined the Mi’kmaw right to not just harvest but also earn a living by trading the catch. Marshall lost in provincial court and was rejected in the court of appeal. But, on a Friday in September 1999, six years after the DFO took Marshall’s nets and boat, the Supreme Court of Canada confirmed that Marshall had a treaty right to catch and sell fish. “Nothing less would uphold the honour and integrity of the Crown,” wrote justice William Ian Corneil Binnie.

But the language of the Marshall decision was opaque. The ruling stated: “The accused’s treaty rights are limited to securing ‘necessaries’ (which should be construed in the modern context as equivalent to a moderate livelihood), and do not extend to the open-ended accumulation of wealth.” Those two words, moderate livelihood, would get caught up in public debate, like a fishbone in the throat, for years to come.

Many wondered why, after so many non-Indigenous people had accumulated wealth from the resources in their territories, the Mi’kmaq were being confined to living “moderately.” The decision didn’t outline any parameters for what constituted a “moderate livelihood.” How would it be measured? More than twenty years later, these questions remain unanswered.

Many non-Indigenous fishers were livid about the ruling, fearing the potential effect on their fisheries. Tensions rose as Mi’kmaw fishers headed out to drop lobster traps without commercial licences, some for the first time. In one instance, around 600 non-Indigenous fishers were reported to have blockaded a harbour. The DFO was not prepared for the ruling or for the unrest it triggered.

“We knew instantly that [the ruling] was going to change our way of life,” recalls Sterling Belliveau, who served as the chairperson of the Lobster Advisory Board for southwestern Nova Scotia at the time. After working as a commercial lobster fisher for thirty-eight years, Belliveau is now retired and keeps busy mending lobster traps. Like many non-Indigenous fishers, he worried about how the ruling would affect his fishing community. He watched as hundreds of boats captained by non-Indigenous fishers went to Yarmouth to protest the ruling. Many demanded a rehearing.

In November 1999, two months after the Marshall decision was released, the court took an unusual step and issued a clarification, known as Marshall 2. In the clarification, the court stated that treaty rights were not unlimited. The government had the power to regulate the industry, but it had an obligation to consult with Indigenous nations if their treaty rights might be affected. The court wrote that treaty rights to catch fish can be limited “on conservation or other grounds.” It offered no clarification on the meaning of “moderate livelihood.” Conflicts on the water escalated.

The period following the Marshall decision is known unofficially as the Lobster Wars. Though the violence began to ease in the early 2000s, by many accounts, the wars never really ended.

Fisheries and RCMP officers, some dressed in riot gear, were reported to have used batons, tear gas, arrests, raids, and trap seizures to stop Mi’kmaw fishers from operating. Indigenous fishers told reporters at the time that DFO officers had pointed guns at them. The DFO denied these allegations. Some news reports described fisheries officers ramming Mi’kmaw fishing boats. Thousands of Mi’kmaw lobster traps were destroyed. Boats operated by Indigenous fishers were sunk. The RCMP laid some charges, against both non-Indigenous and Indigenous fishers.

Much of the violence was concentrated in Miramichi Bay, off the shore of Esgenoôpetitj (Burnt Church First Nation, New Brunswick). One widely circulated video, shot in Miramichi Bay, showed a large government vessel speeding up and running over a small Mi’kmaw fishing boat, forcing the fishers overboard, and then gunning for their vessel again. One Mi’kmaw fisher later described being pepper sprayed by officers while he was still in the water.

An independent consultant, hired by the Canadian government to file a report following the unrest in Miramichi Bay, wrote: “Some tens of millions of dollars were spent on enforcement in an atmosphere that was described to this consultant as resembling certain police state operations.” In 2000, the federal government, controlled by a Liberal majority, tried to quell the Lobster Wars by offering interim fishing deals to the thirty-four communities tied to the Marshall decision. These deals were not an implementation of the ruling: they didn’t address treaty rights. Instead, in exchange for commercial licences, federal funds, and training, bands had to assimilate into existing DFO regulations. The same regulations that Marshall had fought, and won, to be exempted from.

Many bands were concerned that signing the DFO’s deals would infringe on their newly affirmed treaty rights. But, as an extensive body of scholarship has shown, the legacy of colonization and discriminatory Canadian legislation had left many bands struggling with poverty. Mi’kmaw communities could not afford to build up the infrastructure needed to sustain capital-intensive lobster fisheries on their own. For bands trying to provide adequate housing, health services, education, and employment to their members, it was difficult to turn down the government’s offers. According to Jane McMillan’s book, Truth and Conviction, the negotiations fractured Mi’kmaw leadership. By 2007, all but two of the thirty-four communities had signed agreements.

The stress of the conflicts and the lengthy trials took a toll on Marshall’s health. Saddened by the backlash against Mi’kmaw treaty rights, he never ate another lobster. After years of suffering from a chronic respiratory disease, he died in 2009, ten years after the Supreme Court ruling, at the age of fifty-five.

In the fall of 2019—twenty-six years after fisheries officers seized Marshall’s gear in Pomquet Harbour—his eel net was discovered in a DFO office. Salt and mud still clung to the fibres.

“There are serious constitutional issues that DFO has never come to grips with,” says Bruce Wildsmith, the lead lawyer on Marshall’s case. Wildsmith, who lives in Lunenburg County, Nova Scotia, and who isn’t Indigenous, has been working on Mi’kmaw-rights cases since 1974. He acts as legal counsel for the Assembly of Nova Scotia Mi’kmaw Chiefs and the Kwilmu’kw Maw-klusuaqn Negotiation Office.

The court’s ruling, he says, placed the onus on the department to both recognize Mi’kmaw treaty rights and propose regulations for what constitutes a “moderate livelihood.” (Indigenous rights and treaty rights are protected in section 35 of the Constitution Act.) With no progress on either front over the past two decades, the DFO is operating in a legal grey area, he says.

Currently, the DFO issues fishing licences for commercial fishing (including communal commercial licences, which are issued to a band; a band council then allocates a licence to an individual fisher or to band-employed fishers); recreational fishing (which prohibits selling any catch); and the food, social, and ceremonial (FSC) fishery. The latter is a direct outcome of the 1990 Supreme Court decision R. v. Sparrow, which stated that Indigenous people have a right to fish for food, social, and ceremonial purposes. But, according to the DFO, it is illegal to sell FSC catches.

Commercial lobster fishing requires massive investments of capital. According to a 2019 report from the Macdonald-Laurier Institute (MLI), a public-policy think tank, the price of a licence can exceed $2 million, and boats can cost more than $160,000. (Some fishers estimate that boats can cost much more—over $500,000 in some cases.) Since the Marshall decision, the DFO has tried to address the ruling by increasing Mi’kmaw and Wolastoqey involvement in the existing commercial lobster fishery through financial support and training. According to the MLI report, federal funding to promote Indigenous engagement in the commercial lobster fishery between 2000 and 2018 totalled more than $500 million. Some of that funding was spent on a voluntary buyout program through which the government bought licences back from some non-Indigenous fishers and then allocated them to bands as communal licences. The government’s buyouts often included the purchase of fishers’ boats and gear, but a lot of the used fishing gear that was distributed to Mi’kmaw and Wolastoqey communities was found to be worn and too costly to repair.

After the Marshall decision, on-reserve fishing revenue for Mi’kmaw communities in Nova Scotia grew from $2.4 million, in 1999, to just under $52 million, in 2016, according to the MLI report. (That’s a small fraction of the province’s lobster industry: the value of lobster exported from Nova Scotia in 2014, for example, was nearly $580 million.) Contrary to many non-Indigenous fishers’ fears, the report found, the rise of Indigenous commercial fishing did not destabilize the industry.

Some Mi’kmaw leaders and fishers are calling for an alternative fishery, governed by Mi’kmaw authorities, that recognizes their communities’ rights to catch and sell without adhering to DFO regulations. This past August, the Assembly of Nova Scotia Mi’kmaw Chiefs, with the support of the grand council and band councils, released a working document outlining standards for a Mi’kmaw Netukulimk livelihood fishery. (The Mi’kmaw philosophy of Netukulimk can be loosely defined as using the natural bounty provided by the Creator for the well-being and self-support of the individual and the community without endangering that bounty.) The standards are intended as a guide for communities to then set their own regulations for a livelihood-fishery plan, and they outline requirements like registration, accessibility, and consistency with Netukulimk. (Some non-Indigenous fishers are opposed to communities developing their own fishery plans outside of the DFO’s regulations, fearing that a patchwork approach to managing the fishery may harm the future of the industry.)

This past fall, two bands in Nova Scotia launched their own Mi’kmaq-governed fisheries. Sipekne’katik First Nation launched its fishery on September 17, the twenty-first anniversary of the Marshall decision. Potlotek First Nation followed suit in early October. These fisheries are considered illegal by the Crown. “While the public may not comprehend a fishery outside the realm of the Department of Fisheries and Oceans,” Terrance Paul, chief of Membertou First Nation and then co-chair of the Assembly of Nova Scotia Mi’kmaw Chiefs, stated in a press release, “that does not make our fishery illegal.” Later that month, Paul, who has served as the chief of Membertou First Nation, Donald Marshall Jr.’s home community, for thirty-six years, stepped down as co-chair: Membertou First Nation had left the assembly. Paul told the CBC that he blamed the DFO for creating divisions within Mi’kmaw leadership.

In a response to proposals for Mi’kmaq-governed fisheries, Bernadette Jordan, minister of fisheries, oceans, and the Canadian Coast Guard, posted a statement on Facebook directing attention back to a series of deals the department has been trying to negotiate since 2014. These deals, called Rights Reconciliation Agreements (RRAs), are time-limited, legally binding agreements negotiated between the Crown and bands. The agreements outline Indigenous rights, including fishing, for the duration of the RRA (anywhere from ten to twenty-five years). The deals offer conditional access to the existing commercial fisheries and may require Indigenous fishers to conform to DFO regulations. “Until an agreement is reached with DFO, there cannot be a commercial fishery outside the commercial season,” Jordan wrote in her Facebook post in September. “Fishing without a license is a violation under the Fisheries Act.”

The contents of the agreements aren’t public, and the language used to describe them in confidential DFO documents, obtained through an access-to-information request, paints a murky picture at best. (A copy of one of the signed RRAs was also obtained, but the text was entirely redacted.) According to one internal government document, however, an RRA “seeks to reduce the risk of litigation for the term of the agreement.” Bands that sign one of the new deals would have a hard time suing the DFO. It’s not yet clear how this provision would be implemented. RRA negotiations have been taking place behind closed doors.

As of early November, only three bands have signed RRAs—the Maliseet (Wolastoqiyik) of Viger, in Quebec, and, in New Brunswick, the Elsipogtog and Esgenoôpetitj (Burnt Church) First Nations. According to Wildsmith, they did not hold community referendums to guide their decisions. The deals have been publicly denounced in the press by many Mi’kmaw leaders. To some, the RRAs aren’t about “rights” or “reconciliation” at all: they just reinforce the status quo. And, in recent months, the status quo has been rapidly careening out of control.

In early september 2019, in the middle of the night, Ashton Bernard, a fisher from Eskasoni First Nation, in eastern Cape Breton, was stopped by fisheries officers after he pulled into a wharf near Yarmouth. He told the officers that he was fishing for a moderate livelihood. The officers seized his thirty-two crates, about 1,450 kilograms of lobster—more than $20,000 at market prices—and released the crustaceans back into the water, according to a partially redacted document that matches the details of the case. But the officers didn’t charge him that morning. Bernard asked for documentation, some kind of evidence for what they were doing. One of the officers wrote “32 crates seized” on a piece of loose-leaf paper. In May, more than eight months later, Bernard was charged with fisheries violations. His case is now in court.

Bernard’s is one of dozens of similar accounts. Cody Caplin, who is Mi’kmaw and from Ugpi’ganjig, or Eel River Bar First Nation, has had his gear seized multiple times by fishery officers. They have also seized his boat and his trailer. “I been asking the creator to stop this madness and let us fish,” he wrote to me. The DFO later charged Caplin with fishing out of season. He has a court date set for December, but he says his gear was sold at an auction and he was never reimbursed. (When asked to confirm whether gear seized from fishers may be sold at auctions, the DFO pointed to the Fisheries Act, which states, among other things, that when officers seize gear or catch, they “may retain custody of it or deliver it into the custody of any person the officer or guardian considers appropriate.”)

Some Mi’kmaw fishers have developed covert tactics to avoid run-ins with the DFO. Alexander McDonald’s house is a stone’s throw away from Saint Mary’s Bay, where he’s been fishing for nearly half his life—and where he’s been getting charged by the DFO for just as long. “We fish in the fog, we fish at night,” he told me. McDonald, now fifty-eight, is the former chief of Sipekne’katik First Nation and a descendant of Jean-Baptiste Cope, the Mi’kmaw chief who signed the Treaty of 1752.

Other fishers, like Marilynn-Leigh Francis, plan for the tides to hide their traps beneath the water’s surface. “We fish at the most dangerous times because we’re trying to be incognito,” says McDonald.

The DFO’s routine seizure of traps, lobsters, and sometimes boats and trucks force Mi’kmaw fishers off the water, at least for a time. “By charging people and taking them to court, you get them off the water,” says Simone Poliandri, an associate professor of anthropology at Bridgewater State University whose research focuses on Mi’kmaw rights and who spent the summer of 2000 on boats with Mi’kmaw lobster fishers. This approach by the DFO, says Poliandri, is similar to the tactics used in the United States, in the 1970s, by the FBI to suppress Indigenous activists in the American Indian Movement, which sought to address issues of systemic racism against Indigenous people. It has the effect of tying up their time and resources and taking them away from fishing, says Poliandri. If fishers are fighting charges in court and spending money on lawyers, they don’t have the time or the resources to fish.

For Indigenous fishers, it’s often hard to predict when officers will make an arrest, seize their gear without laying charges, or lay charges and then drop them. In any case, “it’s a way of infringing on someone’s rights without legally infringing on their rights,” says Chris Milley, an adjunct professor in the marine-affairs program at Dalhousie University.

The DFO has the power to arrest fishers who are in violation of the Fisheries Act, which includes those fishing without a licence and those fishing outside the department’s seasons. Under the act, officers are authorized to seize anything they believe was used to commit a fisheries offence: boats, vehicles, gear, fish, and any “other thing.” The department can wait up to ninety days before returning seized items if no charges are laid. If charges are laid, five years can pass before the case is heard in court.

McDonald has saved paper copies from his DFO charges and hearings over the years. His most recent charges were laid in 2015, after he went fishing in Saint Mary’s Bay with two of his cousins and his son. While driving home with his catch, he was pulled over by fishery officers. He told the officers that his party had been fishing for a moderate livelihood.

McDonald and the fishers were charged with violating fishery regulations. They spent two years shuttling back and forth from Sipekne’katik First Nation to the courthouse in Digby—a two-and-a-half-hour drive each way—to argue their case. The Crown ultimately dropped the charges. McDonald and the three fishers sued the DFO for racial profiling; he says the case was settled out of court.

Nobody I spoke with could discern a logical pattern in the DFO’s practices. “There is this uncertainty about how they will treat any given situation,” says lawyer Bruce Wildsmith. Which raises the question of what principles, if any, are guiding the department’s conduct—when officers will seize Mi’kmaw traps, lobster, and gear, whether they will lay charges, and why.

On a windy Friday morning in August 2019, I drove south from Digby on Highway 1, a quiet two-lane road that follows the shores of Saint Mary’s Bay. I was headed to the DFO offices in Meteghan to put these questions to the department directly. My cellphone had been lighting up all morning. Fishers were texting and calling to say that officers were out on the water, pulling up Mi’kmaw traps.

As I drove closer, I could see stacks of lobster traps locked behind a metal fence.

Inside the squat building, I spoke with Dwayne Muise, who has worked with the department for nearly two decades. He said that things had become more tense on the water than they’d been in years. He declined to elaborate further and later refused to speak to me again. About a week after our conversation, I heard from Debbie Buott-Matheson, a communications adviser at the DFO. She’d heard that I had spoken with Muise. Any DFO interview requests had to go through her, she told me. After we hung up, I typed her name into Google. Buott-Matheson’s presumably tongue-in-cheek Twitter bio read: “Spin Doctress & dealer in creative truth telling.”

Buott-Matheson refused to arrange a follow-up interview with Muise or with any other DFO officer or representative. Jane Deeks, the press secretary for the DFO’s minister’s office, also refused to arrange any interviews related to moderate livelihood. “It’s a very sensitive subject,” she wrote in an email. She offered to respond to written questions. I told her I’d already sent the DFO a dozen questions and received a paltry reply.

Most of the fishers and legal experts I’d spoken with had the same questions I posed: What is the DFO’s guiding principle when seizing traps, gear, and boats belonging to Mi’kmaw people fishing for a moderate livelihood? What determines whether the DFO will lay charges against Mi’kmaw fishers? And why, two decades on, has the department still not defined what constitutes a moderate livelihood?

The DFO had replied to three of my twelve questions, two of which they’d rewritten in their own words to make them less specific. The responses were similar to the information found on the department’s website. I asked Deeks whether the department could provide a more detailed response. “I can confirm we have nothing more to add,” she wrote back a week later. (The DFO later responded to further questions by email.)

I turned instead to a DFO veteran. David Bishara worked as an officer for thirty-three years and left when he felt that, morally, he couldn’t go on. He had been on the front lines of the Lobster Wars in the early 2000s. And he had been there for the years leading up to Marshall. Bishara had followed orders to board Mi’kmaw vessels; to seize gear, traps, and lobster; to make arrests; and to surveil Mi’kmaw fishers—photographing crates of lobster coming out of the water and following them to fish plants. Bishara had never spoken publicly about leaving the DFO. When I cold-called him, it was as though he had been waiting for someone to ask him about those years.

“Enforcement was pathetic,” he told me. “You didn’t even want to have your uniform on.” For a few years after the Marshall decision, the orders would pivot sporadically, he said. “Until somebody decided, ‘Okay, we’re not gonna go about it this way, we’re gonna go about it with full-fledged enforcement. And we’re gonna go seize gear, and we’re gonna go charge the Native fishermen.’”

Bishara felt that the orders did not respect the Mi’kmaw rights that had been upheld in the Marshall decision. “I blame it on ignorance and poor, poor management.” Now, he says, “I see things deteriorating all over again.” He faults the DFO for the recent breakdown in the fishing community.

I would later find, while listening through audio recordings from a 2018 hearing at the courthouse in Digby, an answer to at least one of the questions that I’d put to the DFO. It was a trial for the charges laid against Alexander McDonald, his son, and two of his cousins in 2015, when the men were fishing lobster outside the DFO’s regulations. Muise, the fisheries officer I spoke with at the DFO offices in Meteghan, was one of the officers involved. He was cross-examined about whether the department’s fishing seasons apply to those fishing for a moderate livelihood.

Under oath, Muise said, simply, “There’s no regulation to deal with moderate livelihood right now.” In other words, when it comes to regulating treaty rights, the DFO doesn’t seem to know why it’s doing what it’s doing either.

After the DFO refused to facilitate any interviews, I called active officers to see if they would speak to me anonymously. Months went by before one called me back. The officer said they’d picked up the phone to call me many times but had gotten scared. Now, exasperated with the department’s mismanagement, they were willing to speak. (Out of fear of repercussions, they spoke with me on condition of anonymity.)

Officers are forced into an impossible position, they explained. “We’re the boots on the ground,” they said. “We just want clear legislation. We don’t have it.” DFO officers are operating in “no man’s land,” the officer said. They and their colleagues take the heat, but the problem doesn’t lie on the front lines: “When you get above the enforcement section,” they said, “that’s where it gets wrong.”

“I’m just caught right dead in the middle.”

One fall day a few years ago, McDonald arrived at the wharf and saw that the thick ropes that moored his boat had been burned off. His boat, Buck and Doe, was nowhere to be seen. It was later found drifting in the middle of Saint Mary’s Bay, on fire. Another time, on a snowy Christmas morning, his lobster pound, on Little Paradise Road, was burned to the ground. It took firefighters hours to put out the flames. The RCMP considered both fires suspicious, though no charges were laid. Attacks like these are seen by many as expressions of the growing animosity within the fishing community.

“I don’t go see a psychiatrist or psychologist or nothing. But people around me see that, when I go fishing, my anxiety’s high,” said McDonald. He has nightmares, too. “Nightmare after nightmare of DFO attacking us.” In another dream, he is asleep on his boat when someone sets him on fire.

Stories of Mi’kmaw fishers’ boats being burned and sunk have made headlines on the East Coast for years. But, in recent months, the clashes between Indigenous and non-Indigenous fishers have catapulted into national and international media.

“I stayed out of this battle as long as I could,” said Colin Sproul from his home in Delaps Cove, on the shore of the Bay of Fundy, last spring. Sproul, a non-Indigenous fifth-generation lobster fisher and president of the Bay of Fundy Inshore Fishermen’s Association, has been watching with concern as Mi’kmaw vessels fish outside the DFO’s seasons and regulations. And it’s not just small skiffs, like the one that Francis works out of, but large-scale boats with crews, he says. Sproul has grown increasingly frustrated that over two decades have passed without any clarity from the DFO about its regulations. The uncertainty of how and when the government will implement the 1999 court ruling, and how that may affect non-Indigenous fishers, ripples throughout rural fishing communities, including Sproul’s. His son, who is thirteen, wants to be a lobster fisher like his dad, his grandfather, and the generations before them. (It’s not uncommon for lobster-fishing licences to be passed down through generations—Sproul’s licence was once his father’s, and it was his grandfather’s before that.) Sproul doesn’t know if his son will have a future in the fishery. Fishing communities like Sproul’s exist because of the lobster fishery. “With no lobster industry, there’s nothing left.”

The federal government has lacked “the political courage” to address the Marshall decision, said Sproul. “The buck has stopped in these communities, and it’s been left for us to sort out,” he added. “It’s completely, patently unfair for the federal government to do that. They have to figure something out legally, in Ottawa, and not leave it to us.” (Three Mi’kmaw parliamentarians have called for the creation of an alternative body that would allow for Mi’kmaq and Wolastoqiyik to work together, directly with the Crown, instead of dealing with the DFO one band at a time.)

A couple of years ago, after Indigenous fishing boats were vandalized, Sproul said, some leaders in the fishing community decided they’d had enough. Impatient with government inaction, Sproul, alongside other non-Indigenous fishing-industry representatives and Mi’kmaw chiefs, started a dialogue group to discuss fishing matters. The informal committee held a handful of meetings and calls about the fisheries, but as tensions escalated, the group unravelled. “Things are about to turn bad,” Sproul messaged me this past August. Shortly afterward, Sipekne’katik First Nation launched its moderate-livelihood fishery and conflicts started to flare.

The aftermath saw weeks of unrest on and off the water. In various incidents, according to news reports, non-Indigenous fishers circled Mi’kmaw vessels, cut their traps, dumped their pots outside a DFO office, and barricaded a wharf to restrict Mi’kmaw fishers’ access to the sea. Non-Indigenous fishers shot flares at a Mi’kmaw vessel. A Mi’kmaw boat was burned. A van belonging to a Mi’kmaw fisher was torched. In October, two lobster pounds used by Mi’kmaw fishers to store their catches were raided and vandalized, and hundreds of dead lobsters were littered on the ground. In one case, two Mi’kmaw fishers—one of whom was Randy Sack, Donald Marshall Jr.’s son—were forced to lock themselves inside the lobster pound while roughly 200 people surrounded the building, trashed it, and threatened to burn it down with the men trapped inside. Though RCMP officers were present, they have been accused of standing idly by. When the pound was destroyed by a fire a few days later, Michael Sack, chief of Sipekne’katik First Nation, demanded military intervention. In mid-October, the government approved increased RCMP presence in the area. Meanwhile, DFO officers continued to seize traps set by Mi’kmaw fishers, according to statements from the Assembly of Nova Scotia Mi’kmaw Chiefs. A week later, the government issued a press release stating that Allister Surette, a former Liberal provincial cabinet minister, had been appointed to serve as a special representative in efforts to “continue to walk the shared path of reconciliation.”

The Sipekne’katik First Nation’s new fishery also stirred concern among neighbouring First Nations: in late October, Carol Dee Potter, chief of Bear River First Nation, whose reserve lies near the southern coast of Saint Mary’s Bay, said her band hadn’t been consulted about how the fishery would affect their own community. Bear River First Nation, wrote chief Potter in a press release, was facing backlash from the unrest, and her community’s long-standing relationships with non-Indigenous fishers were suffering.

Sproul blames the federal government for driving a wedge between Indigenous and non-Indigenous fishers—communities, he said, that “have to share the ocean”—effectively deflecting attention away from the DFO’s own practices. “It’s been incredibly painful,” Sproul said. “I’m fearful for what it means for the future of my relationships with Indigenous people right here in my hometown.”

Kevin Squires, a non-Indigenous lobster fisher and president of the eastern Cape Breton branch of the Maritime Fishermen’s Union, said he hears concerns from members about what the future of their fishery will look like if Mi’kmaw fishers increasingly catch and sell lobster outside of government regulations. “We can’t do our part in preparing our members for the fishery to come when we don’t know,” he said. While he said he respects that the discussions around RRAs are nation to nation and therefore don’t include non-Indigenous fishers’ voices, he fears the impact RRAs might have on less established fishers’ livelihoods.

Echoing the DFO, many non-Indigenous fishers have expressed concern that Mi’kmaw fishing outside DFO regulations will deplete lobster stocks. But, to some, the sustainability argument is a mask. “I don’t think conservation has ever been a sincerely significant factor in the exclusion of Mi’kmaq to the fishery,” said Dalhousie University’s Chris Milley, who has been researching the politics and management of fisheries for decades. (Milley is now assisting bands to develop Netukulimk livelihood-fishery management plans.) To the government and non-Indigenous fishers, said Milley, the health of lobster stocks isn’t as important as the health of the lobster market. That, some suggest, is what they’re really fighting over.

The light-blue sky stretched high across the Atlantic as Marilynn-Leigh Francis and Tiffany Nickerson drove home from the harbour. Their reserve, Acadia First Nation, is less than a ten-minute drive east of where Francis docks her boat at Lobster Rock Wharf.

After driving Nickerson home, Marilynn-Leigh stopped by her mother’s house to say hi before walking across the gravel road to her own home. Her mother, Marilyn Francis, was beading at the kitchen table and watching the cooking show The Chefs’ Line on Netflix.

“They said DFO’s gonna be down there tomorrow taking traps out,” Marilyn said to her daughter, pausing the show. Below the flat screen TV was a banner that read: WE ARE ALL TREATY PEOPLE. A friend had called to tell Marilyn what they’d heard. Marilyn and her family were used to community members calling or messaging or stopping by to let them know about the DFO’s movements.

Marilyn used to fish too. Growing up, she had been taught by her own mother and grandmother about her inherent right to fish, hunt, and harvest. It’s something she’s passed on to Marilynn-Leigh. Like her daughter, Marilyn has had her share of run-ins with the DFO. In 1998, she was charged with violating fishing regulations for fishing lobster without a DFO licence, the same way Marilynn-Leigh fishes today.

“I’m not trying to be a lobster mogul,” Marilynn-Leigh said to me. “I’m trying to be self-sufficient.” She doesn’t use the term moderate livelihood: the word moderate, she says, isn’t right to her. “That’s their word,” she told me, adding that, to her, it means just enough to survive. The Canadian government, she went on, is “so used to us not having anything that even a little bit of something is too much.”

Marilynn-Leigh lives below the poverty line, like many Mi’kmaq living on reserves in Nova Scotia. According to the most recent census, the average annual income among members of Acadia First Nation was $18,042. (The average income on reserves across Nova Scotia was $20,477.) The Indian Act of 1876, and related policies of the Canadian government, displaced and dispossessed Indigenous people from their land and resources. The Crown “gave” small tracts of land, often the least desirable pieces, to Indigenous communities as reserves, while settlers kept the most desirable plots for themselves. Today, Indigenous people have 0.2 percent of their traditional territories as reserve lands.

This past fall, Marilyn posted a photo of six steamed lobsters on Facebook, their shells a fiery red, and wrote: “Would anyone like to barter 6 fresh cooked lobsters for 1 loaf of WW bread, 2% farmers milk, molasses, eggs, bag of dog food and tide. Message me. Welalin.” (Wela’lin is the Mi’kmaw word for “thank you.”) She later posted a photo of the groceries that she’d gotten in the trade and wrote: “That’s what I’m talking about, received my food after bartering cooked lobster. Love it.”

“We barter a lot,” Marilynn-Leigh explained. “If our truck breaks down, barter a mechanic. Go and get gas, ask, ‘Do you want $20? Or do you want lobster?’” Bartering, said Marilynn-Leigh, is like fishing outside the DFO system. “Using our own resources, using our own land,” she said. “Now the government is completely cut out. That’s why they’re pissed.”

Outside Marilyn’s kitchen window were around twenty of Marilynn-Leigh’s lobster traps, some stacked over six feet high. They were piled on the grass where the DFO had left them. Officers had hauled some of her traps out of the water and locked them up in the DFO compound. After Marilynn-Leigh asked for her pots back, an officer dropped them in her yard.

“So, are you gonna have fish with me tonight?” Marilyn asked her daughter.

A piece of halibut was thawing on the counter. The fish had been expensive, said Marilyn, “almost twenty bucks” for a piece that would feed two. She hoped Marilynn-Leigh and her husband would eat with her, as they often did. Marilynn-Leigh said they’d bring potatoes. Later, while Marilynn-Leigh stood at her kitchen sink washing the potatoes, her brother Peter Francis pulled up to her back porch in his pickup truck. He’d just heard from a friend that DFO officers were out on the water. Peter taught Marilynn-Leigh how to fish, and he keeps an eye out for her.

“They didn’t haul in nothing,” Peter told Marilynn-Leigh through the open truck window, his engine still running. “They’re probably getting their bearings for tomorrow. Marking ’em,” he said.

“Oooh, they’re getting ready to attack. Attacking the little Indians,” Marilynn-Leigh teased.

“They’re probably gonna haul tomorrow,” he told her before driving off, his tires kicking up dust.

Marilynn-Leigh texted Nickerson and made plans to go fishing the next morning, when the tide would be low. Then she turned back to the potatoes and put water on the stove to boil.