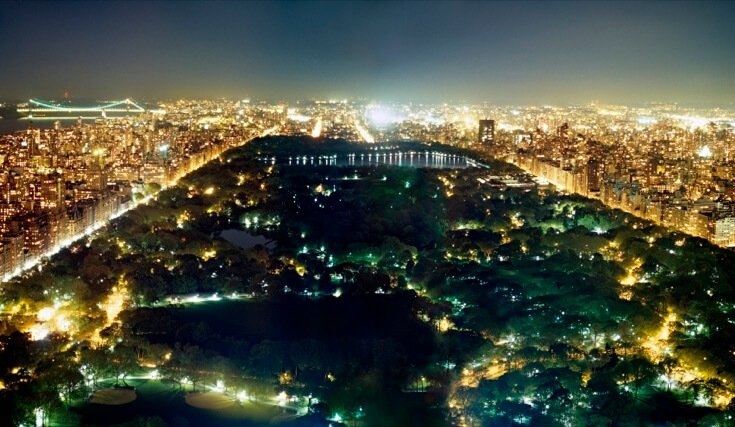

I don’t want to finish the joke. I feel the heat rising in my body, that prickling message from the brain that signals embarrassment, that one that hits your armpits and the back of your knees, reaches like a hand up the nape of your neck and over your forehead. I am tired and not thinking straight, overwhelmed by New York’s twinkling winter lights and dense knots of buildings, hinting at much more beyond. This is not to excuse, rather to explain why, when the kindly cab driver told me his name was Stanley, I said, in an overly forceful tone, a put-on tone attempting God-knows-what, “And where are you from, Stanley? ” To which he said, “I am from Haiti.” His words like little bells. And then I said, “I know a joke about Haiti.”

An hour earlier, I had shuffled off the airplane to Baggage and wrestled my oversized camping backpack—a gift from my father—onto a cart. A man, maybe seeing me flounder, asked where I was from. “Can-a-da!” he exclaimed, half- enjoying the word and half into me being from there. With a wink, he answered his cellphone, the ring a loping hip hop beat I didn’t recognize. “Yo,” he said, and, not waiting for someone to respond, “I’m almost home!”

LaGuardia Airport was shabby and small. Even at the late hour, it was thick with bodies. As instructed by a friend’s sister, a Manhattan expat, I avoided the car service desks; the cars, pictured on sandwich boards, were a series of identical Cutlass Supremes, their windows blacked and seething with potential danger. I was supposed to get a friendly, yellow cab with a friendly, smiling driver. So I did. I know a joke about Haiti, yes I do.

“Oh yes? ” Stanley says gently, his eyes level on the road. Unlike the New York cabbies I’ve pictured (“Follow that car!”), he drives very slowly.

“Uh. Yeah. Have you heard of Dave Chappelle? ” I was raised on stand-up, particularly black comics like Eddie Murphy, Richard Pryor. My mother is a fan, and anyway she’d determined never to conceal any facet of the world—particularly the world of performance—from my sister and me. We were plunked in front of Saturday Night Live and Mr. Dressup alike. As a pop-bottle-glasses-wearing five-year-old, I entertained her high school drama classes with pitch-perfect jokes from Murphy’s Delirious: “Your mother got a mouth in the back of her neck, and the bitch chew like this.” Riotous applause. Eventually, I applied this skill to TV commercials, snl sketches, talk shows. I still do it. Stand-up-wise, Chappelle is a new favourite. Stanley nods.

The prickle is all over my body now, and I want nothing more than to stop this and apologize to Stanley, to explain without actually having to explain that I mean nothing by anything; you see, Stanley, I was raised in a tiny Canadian town where I could get away with it.

“Well, he’s talking about the Elian Gonzalez thing,” I say instead. “You know, the kid from Cuba who showed up on a raft near Miami? ” Stanley nods. “Well, uh, he says, Chappelle says, ‘Don’t worry, I ain’t got no Elian jokes. All I’ll say about it is this: if Elian Gonzalez was Elian Mumumbo, from Haiti, we never would have heard about his ass.’”

Stanley smiles. For one breathless moment, his eyes roll over the rear-view mirror and across mine. Queens turns into Brooklyn, but I do not perceive the change. Stanley nods. “Smart. He is a smart man.”

There is an album I pick up the year I live in New York, off a stack of albums we’re free to take from the music magazine that drew me there. It’s called Show Your Bones, by the Yeah Yeah Yeahs, a band I didn’t think I liked. My nagging secret is that I’m not into much of anything I’ve just heard. I need time—time to listen and time to contemplate—which is frowned upon in the lightning-fast music writing world. (You also never, ever give a record five out of five stars, unless you are Rolling Stone and the album in question is at least fifteen years old.) So at first, I just pretend I do, pocketing the disc for further research. After all, in this office the band is well respected. As I wish to be.

“The second album from New Jersey’s Yeah Yeah Yeahs,” begins the review I might have written, “could tear fans asunder—those who revel in the band’s ability to make them shake it resenting the tender balladry that Karen O. and Co. have cultivated here. But those who were really paying attention saw this softer side in Fever to Tell ’s breakup anthem, ‘Maps.’ And if you think O.’s done stomping around in her art rock finery and deep-throating microphones, think again: spend a few minutes with ‘Warrior’ or ‘Turn Into’ to see a band more complex than, and just as fierce as, ever. (Four out of five stars).”

I listen to Bones the whole way through on my way home one night, the A train typically packed. I recently bought cheap black headphones, because my boss has warned me—producing an online article for corroboration—that the telltale white earbuds invite targeted iPod thievery. I hold them in at stops anyway, to prevent an accidental brush-by yanking.

Trouble at home, travel away, you say. The road don’t like me. Travel away, travel it all away. The road’s going to end on me.

My favourite subway performers, a guy roughly my age and two boys, one about fifteen, the other ten-ish, board in Chinatown and start stretching, doing chin-ups on the bars above them. As the train accelerates out of the station, the middle one props a Timberland boot on a metal armrest and looks around, grinning; the eldest claps, signalling that they are about to dance. In the few minutes between stops, they use the bars to launch themselves into backflips, use each other to swing and roll and pose. It’s somewhere between breakdance and ballet: boots coming within inches of people, nearly grazing their arms, heads, feet, but never connecting. And no music.

Men they like me, ’cause I’m a warrior. A warrior.

The first time I saw this, I was delighted, my mouth agape like a goof. I alone applauded when they were done; apparently, everyone else had seen it before. Now I, too, am someone who has seen the show, but I’m still captive to their initial bravado, that simple clap, a moment of silence, then they begin. It’s weird how my music matches them. I love when the universe does that, like when a high hat is struck in time with a blinking traffic light, or a piano’s arpeggio mirrors the pumping of a cyclist’s pedal.

Yeah, the river it spoke to me. It told me I’m small, and I swallowed it down.

When the subway doors open, the performers stop dancing as if on a dime. I’ve never seen anything so urban, adapted. The doors close. They begin again, and this time the youngest boy catches my eye, glides over, and holds out his palm. I reach for my wallet. Gladly. Instead he grabs my other hand, shakes it, and, straightening out my arm, pushes off into a backflip. It’s perfectly executed, but I clap my hands to my mouth. The trust! Why doesn’t anyone else look at them? And then: I just helped! I was part of it.

I bury my head in my coat, pushing its thick, fur-lined collar against my wet eyes. This happens all the time now, it seems. The city squeezes it out of me. The woman next to me stands, pulling my earbud out. I replace it. My stop approaches.

If I make it at all, I’ll make you want me.

For my first few months in the city, I am a bridge-and-tunnel girl. Back in Vancouver, I rented a Brooklyn apartment off Craigslist, doing what you’re not supposed to do and sending a stranger a month’s rent in advance, as a deposit on a room I’d never seen. I very much wanted to sit on the stoop of a brownstone and meet people from my neighbourhood, which I imagined as a cross between the worlds of Sesame Street, The Cosby Show, and The Godfather. Who can forget Sonny Corleone—the hothead son who reminds my mother of my father—beating up his sister’s husband, Carlo, on a steamy Brooklyn street? The neighbourhood kids, who have been playing in the spray of a fire hydrant, watch as Carlo’s battered body splashes into a puddle. I wanted to be on a stoop in that neighbourhood. Maybe on the next block over, though?

When Stanley drops me off at my new home in the predominantly black Bedford-Stuyvesant area, he looks around uncertainly, asking if I am sure this is the right place. It’s past eleven p.m., and I’m not sure, but if he wants to wait I’ll go check. My landlady, a tiny Egyptian woman, opens the door. She looks like Jasmine from Aladdin—an idealized, safe sort of exotic, with big eyes—and makes my name sound like “Caught-ligne,” which suits me fine. I wave goodbye to Stanley. He waves back.

I am one of several tenants in a building my landlady co-owns with her husband, a rough-edged Latino who hints at having deserted from the army in Iraq. He dangles bits of information like a carrot, daring me to ask. I never do. My room is off the back on the ground floor—servants’ quarters 200 years ago, when Brooklyn was a Dutch settlement. Accordingly, my room is small and dark, with only a well-used mattress in the corner. A single-pane window in the lower half of the wall overlooks the patch of dirt that passes for a backyard. In its centre is an iron stake set into a concrete pad. Attached to the stake is a heavy-duty chain, and at the end of the chain is a beautiful husky named Spirit. I wake up most mornings to Spirit’s lonely black eyes staring directly at my face through the window. I can’t really deal with this, so I start closing the curtains. But I still know he’s there, because later, when the sun shines in, I can see his nose spots smeared all over the glass.

Once, I ask if I can walk Spirit. My landlord looks amused. “Nah,” he says. “We don’t do that.”

In February, a record snowfall blankets New York, and the brown slab of the backyard suddenly becomes several dirty white hills. I look out the window one morning to see that Spirit has pulled down a power line that was previously out of reach. That, or it fell from the weight of the snow, but, regardless, Spirit is happily gnawing on the end of the power line (I say happily because his tail is wagging).

Shit, I think.

At the office, my overuse of the word “shit” is my biggest claim to fame. I am The Canadian, and, like the many bands from my native land that have been breaking through, I am slightly familiar, slightly unfamiliar—in other words, just mysterious enough. I answer questions about cultural enigmas from my homeland (example: “Who is the Canadian equivalent of REM? ” I settle on Sloan). I have a funny accent. But most of all, I’m profuse in the use of “shit.”

This first grabs my boss’s attention when I say, “What the shit? ” during a photocopier incident. “What the what? ” he says, his eyes flashing. Then, slightly louder: “What the shit? Did you just say, ‘What the shit’? ” Now, any good culture writer, for whom OCD is more a job description than a disorder, will stop everything to over-analyze an aspect of cultural difference. Convinced he’d stumbled upon some defining divide between north and south, my boss immediately assigned me to write out, in full, the many uses of “shit” that I know. The resulting document was to be called Shit: A Guide to Canadian Usage.

Shit: A Guide to Canadian Usage

shit coarse slang • noun 1 fecal matter resulting from the processing of food and drink by the digestive system (I just took a shit). 2 something undesirable or of poor quality; literally or figuratively similar to actual shit (This photocopier is shit; this photocopier is a piece of shit).¶ Note that in the latter case, the object in question is even less valuable than shit itself, merely a piece of said shit. 3 in an ironic turn on the original meaning, something highly desirable (You, my friend, are the shit; hot shit; king shit ). • adjective 1 indicative of shit, usually used in the figurative, or even the obscure (He just ate a shit sandwich) (What happened to him was terrible). • prefix (That record was shit town). • interjection 1 an exclamation of anger, disgust, etc. (Shit! ). 2 preceded by the, indicates something at once mysterious and undesirable (Who the shit are you? What the shit is this? ). • transitive verb 1 to expel feces. 2 to carelessly or passively expel something (He shit that song out in a week; let’s shit and split) (Let us depart this unpleasant place, and furthermore expel it from our memories, as one expels feces from the body). • adverb modifies a verb in the negative ( My brother got shit canned ).

shitty adjective (Shitty call, ref! ) • shittily adverb (That poutine was shittily made).

Note: When in doubt about using the word “shit,” just remember that wherever “fuck” works, so does “shit.” A classic example of “fuck” ’s linguistic flexibility, “Fuck those fucking fucks,” can just as easily be “Shit on those shitty shits.” If you can dream it, “shit” can do it. You’re welcome.

In my final year of university, I read a lot of Joan Didion, particularly her non-fiction. She writes of her native state, California, in the way all of us wish we could write about home, perfectly balancing the sense of the personal and the historical. Her ancestors, like many before and after them, made the long and difficult journey from the East in search of the West’s elusive promise. They were almost part of the Donner party. Imagine! Some distant Didion being gnawed by settlers stranded on the top of a mountain.

I read this and thought of my father’s family. Having arrived in Canada from Italy poor and unmarried, my great-grandfather followed the lure of mining jobs in the Elk Valley. In California, gold. In BC, coal. For those immigrants willing to risk being buried alive or blown to bits, the company provided a home that, like its occupants’ lungs, grew gradually black. My great-grandmother died at thirty-eight, from breast cancer, in that house. A generation later, my father was born there. He never strayed far, and eventually started his own hunting, fishing, and backcountry recreation business.

I think, too, of one of his mistresses—a client and a Californian. In a letter my mother later found, the woman invited my father to run away to her, to bring those beautiful little girls with him. My father, when confronted, admitted he had been considering it. His clients were mostly Americans like her, people with money and opportunity. Slightly familiar, slightly unfamiliar—in other words, just mysterious enough.

In New York, I look for Joan Didion, who, having long ago adopted the city as her home, lives on the Upper West or East side; I’m never sure. I know I will never find her, but every tiny old lady with big glasses (there are many of these about) offers a glimmer of possibility. I stare at them. Follow them, occasionally. What else is New York for if not the possibilities of such encounters? I devise a mental scenario in which I am Didion’s neighbour. She and I meet up occasionally and go for lunch. She thoughtfully chews bits of torn bread, mashing them with those flat, lined lips old ladies get. I say, “I don’t know, Joan,” in this fantasy, as if we’re in the middle of some grand conversation we always have about something important.

When, months into my time in the city, an outdated copy of New York magazine ends up in my research pile, I see I’ve missed Didion reading at NYU by one week. One week. What a nasty city this is.

People cross in and out of your vision here. They hesitate to befriend, so everyone you know is like that person at the supermarket who picks up the avocado you dropped and engages you in some small talk about guacamole, or the Mexican drug cartels, or your cousin’s time share near Cabo San Lucas that she keeps bugging you to be part of, or whatever. Almost significant.

The whole time I am in New York, no one tries to date me, and I don’t try to date anyone. At home, I am a dater, the kind of girl who always has a boyfriend. I miss having one, though I miss no one specifically.

Men they like me, ’cause I’m a warrior. A warrior.

One still-cool spring day, my boss takes me out for a beer. He’s my age. We like each other. He’s a pale wreck, because the magazine has just been sold and people are getting fired and he might be next. Earlier in the day, he got hives, which I found fascinating because such reactions to stress seem so extreme. It’s in the same category as women (or men, for that matter, but mostly women) screaming when frightened—like the dial gets yanked up to eleven in nanoseconds. I feel my reactions are muted by comparison. When stressed, I get stomach aches. When frightened, I gasp.

I walk my boss to his apartment and continue on toward the subway, making a pit stop at a Starbucks for tea. I’m at the mouth of the station when my boss taps me on the shoulder. This is blocks, and several minutes, later.

“Were we supposed to kiss back there? ” he asks. It’s a plain, fair question. A lot has happened in the past few days; it’s the kind of situation that brings people together (the Titanic sinks, and Rose runs to Jack, etc.).

“I don’t know. A lot has happened.”

He moves to kiss me. I pull back. “C’mon,” he says, and it’s jocular, cute even. Romantic. I kiss him. It’s dry and quick. We part.

The next day, he apologizes via email. I say it’s okay, but I’m guessing, really.

If I make it at all…

It’s not uncommon to find yourself somewhere familiar here, all of a sudden. I begin to love the backbite of it: I am a stranger to this city, but it is not altogether strange to me. All I had to do to know this place was spend years watching it on a screen. I am walking, and I find myself outside an upscale tennis club, where Annie Hall offers Alvy Singer a ride home. I am walking, and I see the pink neon sign of Tom’s Restaurant, where Jerry Seinfeld and George Costanza sit and talk about nothing. I am walking, and I am under the Washington Square Park arch, where Harry dropped off Sally. I am walking, and I pass the doorway of Fifty-five Central Park West, where the portal to the netherworld opens in Ghostbusters. I am outside Radio City. I am inside Rockefeller Center. I emerge from a subway into Times Square. These moments work wonders.

Across from my brownstone is one of the largest Baptist churches in New York State. I learn this the first Sunday I live there, when a computerized church bell plays “Nobody Knows the Trouble I’ve Seen,” waking me up. I yawn and stretch my arms out into the cold room.

Nobody knows the trouble I’ve seen. Nobody knows but Jesus.

One, two, three. Bedbug bites, but I don’t know this yet. They barely itch. I ignore them. Where have I heard that song?

Nobody knows…

Oh, yeah—I know where. Spaceballs. The princess is locked in jail. The heroes, searching for her, hear a deep, manly voice singing. It’s classic Mel Brooks: the voice belongs to the princess. Jesus, my brain. A vault.

I shower. I dress. I want coffee, but there’s little in the way of such comforts around here. Since my late-night arrival, I have discovered that a) there are no coffee shops here, b) my new nickname is “Lovejuice,” and c) I live around the corner from the Marcy projects, where Jay-Z grew up, and where he filmed the video for “Hard Knock Life.” I am the only white person I see on a regular basis. There was another white guy in my house, but he quickly tired of all the fighting in the owners’ suite, below his. The landlady wouldn’t give him back his damage deposit. He moved out overnight.

I try to make friends. To sit on the stoop. My neighbour is a kind older lady who informs me without prompting on our first meeting that her son is married to a white girl and that they live in Cincinnati, where he teaches high school math. I don’t know how to respond. The woman has a pit bull that barks at passing cars. The dog’s name is Meat. m-e-a-t. We sit on side-by-side stoops, staring out. Meat barks at a car with black tinted windows. “You will hate it here, girl,” my neighbour says.

In my downtown life, I do become quasi-friends with a famous writer who writes a pop culture column at the magazine and has published several books. I actually met him when I was still in school, at a reading in Vancouver. I interviewed him and wrote an article about him, and then sent him that article with a request that if he liked it he endorse my bid for an internship at the magazine. He did.

My desk is stationed right outside his office, which has the effect of making me seem like his secretary, à la Mad Men. He appears sporadically and blasts metal music. On my first day, when the boss reintroduces me to him, the Famous Writer says, “You made it.” This is a statement of fact, not of enthusiasm. I comment on his newly grown beard. He shifts a little in his chair, and I sense, as I did when we went out for beers with a few of my friends after our initial meeting, that I make him nervous. I may be reading into this based on some of his writing, which details his awkward, yet prolific, interactions with women. I think he thinks I want to sleep with him. I don’t, but I’ve never had a man who is older than me and who is also a famous writer think that. I get a little excited about it.

(My suspicion is confirmed when, a few years later, F. W. returns to Vancouver for a reading and we end up drunk in a cab together at the end of the night. I direct the cab driver to his hotel, and he hesitates before exiting, as though I have initiated a situation in which he is expected to invite me up. I say good night, but in my confusion it sounds like “Good night? ” and his eyes widen a little before he dashes out.)

F. W. dates a lovely woman who also works at the magazine, and the two of them have a communal birthday party. There I meet many other famous writers I have read over the years, and I feel highly contented when I am introduced to these people by F. W.’s girlfriend as “a great new writer.” I also feel I am deceiving everyone, so I drink more than I should, speak too loudly, and corner myself with F. W. and some of his famous friends.

By way of introduction, he begins telling a story I’d once shared with him, while his friends’ heads bounce back and forth from him to me like it’s some weird tennis match. The abbreviated version goes like this: My father was on safari in Africa when a water buffalo came out of the bush and trampled him. Apparently, they pursue vendettas. “I was going to write about that,” F. W. says, which is both flattering and awful. I am crying a little bit, but I lean back into the darkness of the bar to hide the tears. “I already did,” I murmur.

Later I go outside for air, and F. W. is sitting on a bench covered, comically, in heaps of gifts; these are mostly flowers for his girlfriend, who deserves them. He is clearly very drunk now, as am I. I sit on a little corner of the bench. No one else is around.

“How are you? ” I say. He sighs, and it’s a big one. “Kaitlin, this is not… now is not the time.”

It’s the worst blizzard the eastern seaboard has seen in years, and I’m out in boots and a nightie, trying to convince a dog to stop chewing on a downed power line by saying, “Shoo!” If I had a cigarette, I could be my mother, leaning into my father’s truck window, the chugging exhaust from his diesel engine masking any stilted conversation they might be having about the child support or why he’s picking us up at 10 p.m. instead of 1 p.m. The usual. My mother, slip-sliding back up the driveway in her Sorels. Coming in the door, her face sad and angry, and saying, “Go on.” My sister and I taking our little backpacks out into the night.

The damn dog won’t listen. He’s scooting away with the wire in his mouth, his eyes crazed, in escape mode. He doesn’t want to give up his treat. I relent, go back inside.

I draw the curtains, pile on layers of clothes, and venture out. There is no one, literally no one, about. Eventually, I see two or three people, heads down, hurrying toward home. I don’t see the rush. It’s not all that cold, and the snow is calm, steady.

I make it as far as Astor Place, the first real subway stop that seems like Manhattan to me. I push the cube, a public art piece on a pivot, around a few times. It squeals in the damp, a high-pitched wail that only makes it a few feet before the snow quashes it. I can’t see very far right now. But who needs to?

In the dampness of late March, weeks before I leave for a tidy apartment in Greenwich Village (where, among other claims to fame, Dylan played his first New York show, at Café Wha?), my landlord’s husband splits, taking Spirit with him. Or so I think, and for a few days I miss the dog’s strange eyes, his head cocked, looking in on me. Then the ex returns to collect some things. I’m sitting on the stoop. He stops to chat, lamenting about the ruins of marriage and his tendency to run from things in life, like his career in the armed forces. (I still do not take the bait.) He notices the proliferation of bedbug bites on my arms, my now near-constant itching. “She won’t admit it’s bedbugs, will she? ” he says, shaking his head. I tell him I’m moving out. He says something about he and I getting together for a coffee, which I realize later is a come-on.

“How is Spirit? ” I ask. His face screws instantly into anger. He is one of these people who dials to eleven in nanoseconds. I sense he is a hitter. I have been around hitters; he has that feel.

“Spirit is gone,” he says. Gone. I think of that Monty Python sketch. The parrot. Left? Flown? Shuffled off this mortal coil? Which? “Spirit is in Alaska, at an animal preserve.”

I think about this for a moment.

“That kid,” he says, “the one that moved out in the middle of the night. He called animal control.” And then: “Spirit was 100 percent timber wolf.”

The bread arrives. Focaccia. Between bites, her mouth full: “Why are you still here? ”

“I don’t know, Joan.” I wish this place had balsamic vinegar in olive oil on little plates. I love that. Her eyebrows, framed by that impish old face, rise.

“C’mon,” she says. It’s cute, how she says it. Convincing. I’m reminded of a sentence of hers, so she says it: “You have to pick the places you don’t walk away from.”

“I don’t know, Joan.” That’s all I ever say in these conversations. Joan Didion shakes her head at me. I don’t blame her. She puts on her big glasses, gets up, and walks away.

The river, it spoke to me. It told me I’m small. And I swallowed it down.

“Go home,” she shouts back, before gliding, cool as shit, out the door.

Travel away, travel it all away. The road’s going to end on me.

This appeared in the May 2010 issue.