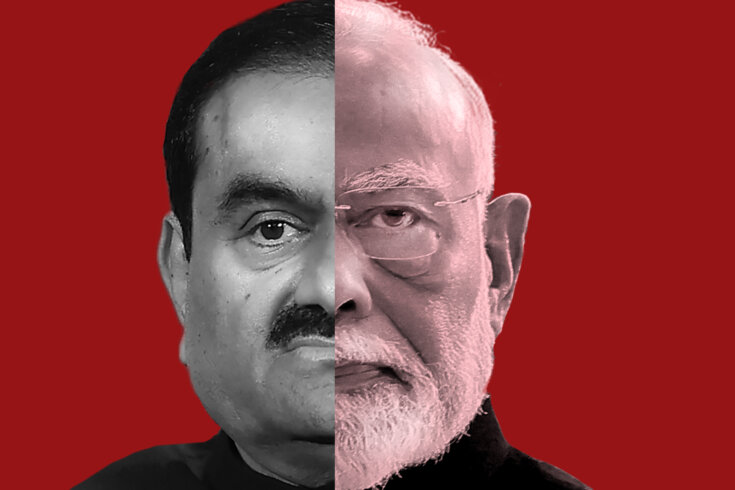

One might say Gautam Adani, among the richest men in the world, is by far Narendra Modi’s favourite tycoon. So much so that when Modi was to be first sworn in as India’s prime minister after sweeping the 2014 general election, the private aircraft he travelled by to New Delhi prominently displayed the logo of the businessman’s multinational conglomerate, the Adani Group. The sixty-two-year-old Adani has been close to Modi for more than two decades. The stars of the two men have risen in tandem since 2002, soon after Modi first became the chief minister of the state of Gujarat, where Adani’s firms benefited tremendously from favourable government decisions.

Adani started his business journey by helping his brother run a small plastics factory in Ahmedabad, Gujarat’s biggest city, and later began importing PVC in 1983. Subsequently, he formed the Adani Group, which started out as a commodities trading firm in 1988. From these humble origins, the group has now expanded into infrastructure, power generation, mining, gas distribution, renewable energy, airports, cement, and media—its share prices rising to stratospheric levels after Modi’s ascent to the prime minister’s post. In Modi’s first year in office, the market value of the group rose by approximately $5.7 billion (US, in today’s terms).

Adani has acquired the operations of eight airports in the country over the past decade, in addition to operating thirteen ports. Taken together, the group accounts for about a quarter each of India’s air passenger footfalls and seaport capacity. Recently, the Guardian reported that the Indian government relaxed national security protocols to enable the construction of a renewable energy park within a kilometre of India’s border with Pakistan—a project Modi launched in 2020 and now with the Adani Group.

This close relationship between Adani and Modi came into sharp focus internationally when, this past November, American federal prosecutors accused the businessman of a conspiracy to commit bribery and defraud investors on the basis of false statements. Prosecutors alleged that Adani and his associates promised to pay more than $250 million (US) to Indian government officials to secure lucrative solar power contracts for Adani Green Energy Limited and Azure Power Global Limited—deals projected to generate $2 billion (US) in profits over two decades—before misleading Wall Street.

The situation arose as the Adani Group had tapped American markets to fund its expansion in recent years. Adani Green and Azure Power were seeking to land various projects overseen by the Solar Energy Corporation of India, an Indian government undertaking. Adani Green allegedly paid the bribes on behalf of both companies and then sought payment from Azure for approximately one-third of the amount.

The Adani Group has said the charges are “baseless” and that it would defend itself legally.

The indictment also charged seven other businessmen, including Adani’s close associates and his nephew, with wrongdoing. These include three former executives from Quebec’s largest pension fund, Caisse de dépôt et placement du Québec—Cyril Cabanes, Saurabh Agarwal, and Deepak Malhotra—who all held high-ranking positions at the fund and were reportedly accused of obstructing a grand jury, the Federal Bureau of Investigation, and the US Securities and Exchange Commission. (The CDPQ was the top stakeholder in Azure Power as of last March.) The CDPQ has said that the services of all three employees were terminated in 2023 and that it is co-operating with American authorities.

This legal case has significant implications for India as Adani’s business ventures are deeply intertwined with Modi’s political and economic strategies. The controversy has strained India’s global relations and investor confidence, risks damaging India’s economic standing and reputation, and highlights the dangers of crony capitalism in the country today. Alongside recent allegations that India’s home minister, Amit Shah, orchestrated a deadly campaign against Sikh separatists in Canada, the case has intensified international scrutiny of Modi, exposing the unchecked excesses of his regime.

Adani’s profile and influence rose rapidly after 2014. Everywhere that Modi went as prime minister, Adani was “sure to go.” Many of his international deals were struck soon after Modi’s official visits to certain countries or after heads of government visited India. To give but three examples:

In 2023, Sri Lanka chose Adani Green to invest $442 million (US) in a wind power project in the country. The year before, a top Ceylon Electricity Board official, appearing before a parliamentary panel in Colombo, had spoken of Modi pressuring then Sri Lankan president Gotabaya Rajapaksa to approve the agreement. The official subsequently withdrew his statement and resigned.

After infrastructure deals were controversially awarded to the businessman last year, former Kenyan prime minister Raila Odinga claimed that he was introduced to the Adani Group by Modi as the chief minister of Gujarat over a decade ago. He said Modi had organized a visit by a Kenyan delegation to the Adani Group’s projects, including a port, a power plant, a railway line, and an airstrip developed from a swamp donated by the Indian government. While there is no direct link between the current controversial deals under Modi’s premiership and his actions over a decade ago as Gujarat’s chief minister, the pattern highlights how he consistently operates when it comes to Adani.

When Sheikh Hasina was prime minister of Bangladesh, Adani reached a deal to generate 1,600 MW of power at Godda in India and transmit the electricity to the neighbouring country, with the coal reportedly being imported from his mines in Australia. The project was seen as a “sweetheart deal” in return for Modi’s political and diplomatic backing of Hasina, who faced Western pressure over democratic backsliding and human rights abuses. But after a popular uprising toppled the India-friendly Hasina last year—forcing her to flee to India, where she remains—the project has faced turmoil amid allegations of exorbitant pricing.

Modi allegedly helped Adani expand his international business interests—in ports, airports, electricity, coal mining, and weapons—in numerous countries, including Australia, Bangladesh, Vietnam, Greece, Indonesia, Israel, Kenya, Nepal, Sri Lanka, and Tanzania. By spearheading initiatives of strategic political importance, often aimed at countering China’s growing influence, the Adani Group came to be seen as the face of India’s development projects around the world. A college dropout and a self-made entrepreneur, Adani emerged as an instrument of Modi’s foreign policy.

As Modi’s India deepened its partnership with the Joe Biden administration, Adani secured an official endorsement from the United States. In November 2023, the US International Development Finance Corporation announced a $553 million (US) loan for the development of a deep-water container terminal at Port of Colombo in Sri Lanka. The Adani Group’s port-operating arm had a 51 percent share in the consortium developing the terminal.

The loan was widely perceived as American recognition of Adani’s corporate practices and his ability to develop world-class infrastructure—particularly as it came just months after the group was hit by allegations from Hindenburg Research. The US-based short-selling firm accused Adani of “pulling the largest con in corporate history.” Hindenburg, which profited from bets against Adani’s stock, alleged that the conglomerate engaged in financial manipulation.

The January 2023 report triggered a market rout, wiping out more than $150 billion (US) from the group’s combined market value at its peak. By late February, Adani’s total market capitalization had fallen to just 35.4 percent of its pre-Hindenburg level. One of the most serious charges centred on round tripping—wherein money is transferred between entities before being funnelled back, to create the illusion of inflated revenue. Hindenburg accused the Adani family of using offshore tax havens to manipulate share prices, violating Indian regulatory guidelines.

Despite widespread criticism, India’s financial regulators took little action, and the judicial system did not press for further scrutiny. Instead, Adani’s camp successfully reframed the controversy as an attack on India’s sovereignty, with the company releasing a video of a representative making a statement against the backdrop of the national flag.

While India’s political opposition was vocal in criticizing Adani’s close ties to Modi, the prime minister and his Bharatiya Janata Party remained largely silent. It was consistent with Modi’s broader strategy: throughout his decade in power, he has not held a single press conference in India, barring one in 2019 where he let then party president Amit Shah field all the questions.

Yet Adani staged a remarkable turnaround. By early 2024, shares of some of his companies had rebounded to record highs. In a January 2024 note, US brokerage firm Cantor Fitzgerald described Adani Enterprises, the group’s flagship company, as “at the core of everything India wants to accomplish.”

Adani may have been flying high, but like Icarus, he flew too close to the sun. The American indictment is the toughest challenge he faces in his astonishing journey.

After the indictment, Modi maintained his usual silence, but his party spokespersons lashed out at the US in a series of posts on X. They said that the Department of State and the American “Deep State” were conspiring with India’s political opposition with a “clear objective to destabilize India.”

Leaving no one in doubt that the party considered the American legal action as an attack on India itself, the extraordinarily aggressive stance caught most observers by surprise. A spokesperson for the Department of State called the accusation “disappointing,” while the Indian external affairs ministry refused to respond to journalists’ queries on the subject.

Modi, who has total control over the party, did not restrain the spokespersons or ask his party to delete the posts. In contrast, when another of his party spokespersons had made a remark against the Prophet Muhammad on a television debate in 2022, she was soon suspended from the party after strong protests from Qatar and other Islamic countries. The episode revealed how deeply Modi and his party see their interests connected with Adani’s. They would want the world to believe what Cantor Fitzgerald wrote in its note in January 2024: “Adani is too big to ignore, and for India, we believe the country needs Adani as much as Adani needs the country.” However, Modi is not India, and though Adani may be serving Modi’s interests, his actions have caused immense damage to India’s interests.

The US has been one of India’s closest strategic partners, crucial for New Delhi as it navigates an uncertain geopolitical landscape and faces up to an ascendant China along its borders and in the region. With Donald Trump back as president, there is even greater uncertainty and unpredictability about the future. He has already criticized India for imposing high tariffs and pursuing protectionist policies that restrict imports from the US. In a move that took New Delhi by surprise, Trump invited Chinese president Xi Jinping, but reportedly not Modi, for his presidential inauguration, even as the Indian government makes much of Modi’s personal close ties with Trump, with the two having held rallies in Houston and Ahmedabad before the 2020 US presidential polls.

Last month, ahead of Modi’s visit to the US, Trump signed an executive order directing the attorney general to pause the enforcement of the Foreign Corrupt Practices Act, which seeks to prevent American and foreign companies from bribing officials of foreign governments, and which was used to launch the bribery investigation against the Adani Group. While this may come as relief to the group, it remains to be seen what stand the Department of Justice takes after the six-month review period mentioned in the executive order is over.

Trump is proud to be seen as a transactional dealmaker. Western countries can exploit the corruption charges against Adani as leverage to extract geopolitical payoffs from Modi. Any attempt to get the US to efface the charges against Adani would likely come at a cost that India would ultimately have to bear. Modi may have intended to position Adani as a sign of his global strength, but the beleaguered businessman has ended up becoming India’s strategic vulnerability.

Things are no better in South Asia, where India’s smaller neighbours find Adani a soft target in hitting out at the Modi government. Bangladesh is pressing the group to renegotiate their power deal, while Adani Green withdrew from its wind power projects in Sri Lanka after similar pressure. In Africa, Kenyan president William Ruto announced the cancellation of two Adani projects. Meanwhile, the group has withdrawn its request for Development Finance Corporation financing from the US for its terminal project in Colombo. The US agency had earlier said it was “actively assessing the ramifications” of the bribery allegations.

The group is also dealing with financial pressures following the US indictment. The group’s share prices have seen some fluctuation, and future investments from global sources, particularly from French company TotalEnergies, which has a 19.75 percent stake in Adani Green, are uncertain. “Until such time when the accusations against the Adani group individuals and their consequences have been clarified, TotalEnergies will not make any new financial contribution as part of its investments in the Adani group of companies,” the French company said. Half of the group’s $27.5 billion (US) long-term debt is reportedly borrowed from overseas, adding to the financial strain.

For India to achieve sustained economic growth and improvements in human development, foreign investment and technology are crucial. Investors, wary of China, seek a stable legal environment and regulatory adherence. The Adani controversy has laid bare significant flaws in India’s regulatory and governance frameworks—revealing inadequate oversight, potential conflicts of interest, and a lack of transparency in financial dealings—further highlighted by the ruling party’s anti-American rhetoric.

The close ties between Modi and Adani have amplified concerns about the systemic weaknesses of crony capitalism in India. Modi faces a stark choice: favouring Adani or positioning India as a prime destination for global capital. He could choose to publicly dissociate himself from Adani, allowing a free parliamentary debate and an enquiry by a parliamentary committee. His government could institute stronger regulations, more effective enforcement, and a re-evaluation of the close ties between business and government. But currently, it appears he is choosing his ally over the nation’s economic interests.

The Adani controversy also comes at a time when the Modi administration is already under heightened international scrutiny with Amit Shah, another of the prime minister’s closest allies, facing the serious allegations of orchestrating a campaign against Sikh separatists in Canada. The two episodes have exposed an intricate web of corruption, influence, and illegal actions that have consequences far beyond India’s borders.

While India’s ruling dispensation has managed to suppress or dismiss such allegations domestically, the international stage, particularly the US, is proving to be a tough battleground where these issues are laid bare for closer scrutiny and investigation. The inability to control the narrative abroad has led to a clearer picture of Modi’s political schema, highlighting the impunity with which his closest allies often operate within India.

Making matters worse, India’s national security adviser, Ajit Doval, did not travel to the US with Modi this past September—which many believed was because of a legal case filed by a Sikh separatist in that country. Once is a mistake, twice is a coincidence, but three times is a pattern. To have three of his closest partners in trouble is not a comment on the incompetence or misfortune of Shah, Adani, or Doval but a bold statement on Modi and his populist, nationalist, and authoritarian tendencies.

Modi’s supporters argue he is emulating the 1960s South Korean model of rapid economic growth, where politically connected conglomerates, or chaebols, like Hyundai, Daewoo, and Samsung, thrived on government contracts and subsidies in return for political kickbacks.

However, a more fitting comparison is with the crony capitalism of Vladimir Putin’s Russia, where Kremlin-linked oligarchs have risen to serve geopolitical aims while amassing personal fortunes. Rather than producing a global business icon, Modi has left India diminished on the world stage.

On Friday, April 25, join us for The Walrus Talks at Home: Tariffs. Four expert speakers will discuss what the U.S. tariffs on Canada mean, both now and in the future. Join us online. Register here.